A Divided Hungary in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storia Militare Moderna a Cura Di VIRGILIO ILARI

NUOVA RIVISTA INTERDISCIPLINARE DELLA SOCIETÀ ITALIANA DI STORIA MILITARE Fascicolo 7. Giugno 2021 Storia Militare Moderna a cura di VIRGILIO ILARI Società Italiana di Storia Militare Direttore scientifico Virgilio Ilari Vicedirettore scientifico Giovanni Brizzi Direttore responsabile Gregory Claude Alegi Redazione Viviana Castelli Consiglio Scientifico. Presidente: Massimo De Leonardis. Membri stranieri: Christopher Bassford, Floribert Baudet, Stathis Birthacas, Jeremy Martin Black, Loretana de Libero, Magdalena de Pazzis Pi Corrales, Gregory Hanlon, John Hattendorf, Yann Le Bohec, Aleksei Nikolaevič Lobin, Prof. Armando Marques Guedes, Prof. Dennis Showalter (†). Membri italiani: Livio Antonielli, Marco Bettalli, Antonello Folco Biagini, Aldino Bondesan, Franco Cardini, Piero Cimbolli Spagnesi, Piero del Negro, Giuseppe De Vergottini, Carlo Galli, Roberta Ivaldi, Nicola Labanca, Luigi Loreto, Gian Enrico Rusconi, Carla Sodini, Donato Tamblé, Comitato consultivo sulle scienze militari e gli studi di strategia, intelligence e geopolitica: Lucio Caracciolo, Flavio Carbone, Basilio Di Martino, Antulio Joseph Echevarria II, Carlo Jean, Gianfranco Linzi, Edward N. Luttwak, Matteo Paesano, Ferdinando Sanfelice di Monteforte. Consulenti di aree scientifiche interdisciplinari: Donato Tamblé (Archival Sciences), Piero Cimbolli Spagnesi (Architecture and Engineering), Immacolata Eramo (Philology of Military Treatises), Simonetta Conti (Historical Geo-Cartography), Lucio Caracciolo (Geopolitics), Jeremy Martin Black (Global Military History), Elisabetta Fiocchi Malaspina (History of International Law of War), Gianfranco Linzi (Intelligence), Elena Franchi (Memory Studies and Anthropology of Conflicts), Virgilio Ilari (Military Bibliography), Luigi Loreto (Military Historiography), Basilio Di Martino (Military Technology and Air Studies), John Brewster Hattendorf (Naval History and Maritime Studies), Elina Gugliuzzo (Public History), Vincenzo Lavenia (War and Religion), Angela Teja (War and Sport), Stefano Pisu (War Cinema), Giuseppe Della Torre (War Economics). -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta Making Magyars, Creating Hungary: András Fáy, István Bezerédj and Ödön Beöthy’s Reform-Era Contributions to the Development of Hungarian Civil Society by Eva Margaret Bodnar A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics © Eva Margaret Bodnar Spring 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract The relationship between magyarization and Hungarian civil society during the reform era of Hungarian history (1790-1848) is the subject of this dissertation. This thesis examines the cultural and political activities of three liberal oppositional nobles: András Fáy (1786-1864), István Bezerédj (1796-1856) and Ödön Beöthy (1796-1854). These three men were chosen as the basis of this study because of their commitment to a two- pronged approach to politics: they advocated greater cultural magyarization in the multiethnic Hungarian Kingdom and campaigned to extend the protection of the Hungarian constitution to segments of the non-aristocratic portion of the Hungarian population. -

The Hungarian Historical Review

Hungarian Historical Review 5, no. 1 (2016): 5–21 Martyn Rady Nonnisi in sensu legum? Decree and Rendelet in Hungary (1790–1914) The Hungarian “constitution” was never balanced, for its sovereigns possessed a supervisory jurisdiction that permitted them to legislate by decree, mainly by using patents and rescripts. Although the right to proceed by decree was seldom abused by Hungary’s Habsburg rulers, it permitted the monarch on occasion to impose reforms in defiance of the Diet. Attempts undertaken in the early 1790s to hem in the ruler’s power by making the written law both fixed and comprehensive were unsuccessful. After 1867, the right to legislate by decree was assumed by Hungary’s government, and ministerial decree or “rendelet” was used as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Not only could rendelets be used to fill in gaps in parliamentary legislation, they could also be used to bypass parliament and even to countermand parliamentary acts, sometimes at the expense of individual rights. The tendency remains in Hungary for its governments to use discretionary administrative instruments as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Keywords: constitution, decree, patent, rendelet, legislation, Diet, Parliament In 1792, the Transylvanian Diet opened in the assembly rooms of Kolozsvár (today Cluj, Romania) with a trio, sung by the three graces, each of whom embodied one of the three powers identified by Montesquieu as contributing to a balanced constitution.1 The Hungarian constitution, however, was never balanced. The power attached to the executive was always the greatest. Attempts to hem in the executive, however, proved unsuccessful. During the later nineteenth century, the legislature surrendered to ministers a large share of its legislative capacity, with the consequence that ministerial decree or rendelet often took the place of statute law. -

Download Report 2010-12

RESEARCH REPORt 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover: Aurora borealis paintings by William Crowder, National Geographic (1947). The International Geophysical Year (1957–8) transformed research on the aurora, one of nature’s most elusive and intensely beautiful phenomena. Aurorae became the center of interest for the big science of powerful rockets, complex satellites and large group efforts to understand the magnetic and charged particle environment of the earth. The auroral visoplot displayed here provided guidance for recording observations in a standardized form, translating the sublime aesthetics of pictorial depictions of aurorae into the mechanical aesthetics of numbers and symbols. Most of the portait photographs were taken by Skúli Sigurdsson RESEARCH REPORT 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Introduction The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG) is made up of three Departments, each administered by a Director, and several Independent Research Groups, each led for five years by an outstanding junior scholar. Since its foundation in 1994 the MPIWG has investigated fundamental questions of the history of knowl- edge from the Neolithic to the present. The focus has been on the history of the natu- ral sciences, but recent projects have also integrated the history of technology and the history of the human sciences into a more panoramic view of the history of knowl- edge. Of central interest is the emergence of basic categories of scientific thinking and practice as well as their transformation over time: examples include experiment, ob- servation, normalcy, space, evidence, biodiversity or force. -

Raimondo Montecuccoli” in Riva Trigoso

FINCANTIERI LAUNCHES THE THIRD PPA “RAIMONDO MONTECUCCOLI” IN RIVA TRIGOSO Trieste, March 13, 2021 – Today, the launch of the third Multipurpose Offshore Patrol ship (PPA) “Raimondo Montecuccoli” took place at Fincantieri’s shipyard in Riva Trigoso (Genoa). The ceremony, held in a restricted format and in full compliance with anti-contagion requirements, was attended by Sen. Stefania Pucciarelli, the Italian Undersecretary of Defence representing the Minister Lorenzo Guerini, Adm. Eduardo Serra, Italian Navy Logistic Commander, and Giuseppe Giordo, General manager of the Naval Vessel division of Fincantieri. Godmother of the ship was Mrs. Anna Maria Pugliese, daughter of Admiral Stefano Pugliese, who was Commander of the light cruiser “Montecuccoli”, which entered into service in 1935 and was uncommissioned from the Italian Navy fleet in 1964. This vessel, third of seven, will be delivered in 2023 and it is part of the renewal plan of the operational lines of the Italian Navy vessels, approved by the Government and Parliament and started in May 2015 (“Naval Act”) under the aegis of OCCAR (Organisation Conjointe de Cooperation sur l’Armement, the international organization for cooperation on arms). Vessel’s characteristics: PPA – Multipurpose Offshore Patrol Ship The multipurpose offshore patrol vessel is a highly flexible ship with the capacity to serve multiple functions, ranging from patrol with sea rescue capacity to Civil Protection operations and, in its most highly equipped version, first line fighting vessel. There will be indeed different configurations of combat system: starting from a “soft” version for the patrol task, integrated for self-defence ability, to a “full” one, equipped for a complete defence ability. -

52Zsolt Torok.Pdf

LUIGI FERDINANDO MARSIGLI (1658-1730) AND EARLY THEMATIC MAPPING IN THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY Zsolt TÖRÖK Department of Cartography and Geoinformatics Eötvös Loránd University [email protected] LUIGI FERDINANDO MARSIGLI (1658–1730) ÉS A KORAI TEMATIKUS TÉRKÉPEZÉS A KARTOGRÁFIA TÖRTÉNETÉBEN Összefoglalás A tematikus kartográfia gyökerei a 17. századig nyúlnak vissza, de rohamos kiterjedése a 19. század első felében kezdődött. A modern kartográfiában az általános térképeket a tematikussal vetik össze, utóbbit a topográfia térképen alapuló, később kifejlődött típusnak tartják. A tanulmány kétségbe vonja ezt az elfogadott nézetet és történeti megközelítést javasol. A tematikus probléma megoldásához a kartográfiát különböző térképezési módok együtteseként kell felfogni. A tematikus térképészeti mód az európai Felvilágosodás idején rohamosan fejlődött, de a kezdetek és a korai története homályos. Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli (1658–1730), a művelt olasz gróf a török háborúk idején katonai térképészként szolgált Magyarországon. Marsigli tudományos érdeklődésének középpontjában a Duna állt. Az 1699-es karlócai békeszerződés után a Habsburg–Ottomán határvonal kijelö- lését és térképezését irányította. Johann Christoph Müller segítségével tematikus térképeket készített: számos térképet a határvonalról, és különleges témákat bemutató mappákat (kereskedelmi, postai, járványügyi). A kézi- ratos térképek a nyomtatott tematikus térképek, diagramok és metszetek előfutárai voltak, amelyek a gazdagon illusztrált, hat kötetes monográfiában, a Danubius Pannonico Mysicus-ban jelentek meg (1726). Az első kötet földrajzi része (általános és részletes) hidrográfia térképeket, a történelmi kötet a római emlékeket bemutató régészeti térképeket tartalmaz. A Duna-monográfia harmadik kötete az első bányászati atlasznak tekinthető. Marsigli tematikus térképész volt, akinek azonban saját maga számára alaptérképeit is el kellett készítenie. Ez a fő oka annak, amiért nem tematikus térképészként, hanem az ország pontosabb, felmérésen alapuló általános térképe szerzőjeként tartják számon. -

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: the Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: The Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918 MICHAEL LAURENCE MILLER WO OF THE MOST ICONIC PHOTOS of the 1956 Hungarian revolution involve a colossal statue of Stalin, erected in 1951 and toppled on the first day of the anti-Soviet uprising. TOne of these pictures shows Stalin’s decapitated head, abandoned in the street as curious pedestrians amble by. The other shows a tall stone pedestal with nothing on it but a lonely pair of bronze boots. Situated near Heroes’ Square, Hungary’s national pantheon, the Stalin statue had served as a symbol of Hungary’s subjugation to the Soviet Union; and its ceremonious and deliberate destruction provided a poignant symbol for the fall of Stalinism. Thirty-eight years before, at the beginning of an earlier Hungarian revolution, another despised statue was toppled in Budapest, also marking a break from foreign subjugation, albeit to a different power. Unlike the Stalin statue, which stood for only five years, this statue—the so-called Hentzi Monument—had been “a splinter in the eye of the [Hungarian] nation” for sixty-six years. Perceived by many Hungarians as a symbol of “national humiliation” at the hands of the Habsburgs, the Hentzi Monument remained mired in controversy from its unveiling in 1852 until its destruction in 1918. The object of street demonstrations and parliamentary disorder in 1886, 1892, 1898, and 1899, and the object of a failed “assassination” attempt in 1895, the Hentzi Monument was even implicated in the fall of a Hungarian prime minister. -

Camoenae Hungaricae 3(2006)

Camoenae Hungaricae 3(2006) SÁNDOR BENE ACTA PACIS—PEACE WITH THE MUSLIMS (Luigi Ferdinando Marsili’s plan for the publication of the documents of the Karlowitz peace treaty)* Scholars and spies Even during his lifetime, the keen mind of the Bologna-born Luigi Ferdinando Marsili was a stuff of legends—so much so that, soon after his death in 1730, the Capuchin monks of his city severed the head of the polymath count from his body and exhibited it in the crypt of their church on the Monte Calvario. Perhaps they hoped to benefit from the miraculous powers of one of the most enlightened minds of the century, perhaps they were under pressure from the beliefs of their flock to permit the veneration of the new, profane relic, it is hard to tell. In any case, the head was a peculiar testimony to the cult of relics, apparently including the bodily remains of scholars, which refused to die down in the age of reason—until it was eventually reunited with its body in the Certosa ceme- tery in the early 19th century when Napoleon disbanded the monastic orders.1 It is not inconceivable that the head of the count granted a favour or two to those beseeching it, however, the whole thing did constitute a rather improper use for a human head… At any rate, the story is highly emblematic of the way that Marsili’s legacy—an in- credibly valuable collection of nearly 150 volumes of manuscripts2—was treated by re- searchers of later generations. Scholarly interest in the Marsili papers was divided according to the researchers’ fields of interest—the botanists looked for material on plants,3 cartogra- * The preparation of this paper has been supported by the OTKA research grant Documents of the Euro- pean Fame of Miklós Zrínyi (Nr T 037477) but I have been regularly visiting Bologna for research purposes since 1997. -

The English-Language Military Historiography of Gustavus Adolphus in the Thirty Years’ War, 1900-Present Jeremy Murray

Western Illinois Historical Review © 2013 Vol. V, Spring 2013 ISSN 2153-1714 The English-Language Military Historiography of Gustavus Adolphus in the Thirty Years’ War, 1900-Present Jeremy Murray With his ascension to the throne in 1611, following the death of his father Charles IX, Gustavus Adolphus began one of the greatest reigns of any Swedish sovereign. The military exploits of Gustavus helped to ensure the establishment of a Swedish empire and Swedish prominence as a great European power. During his reign of twenty-one years Gustavus instituted significant reforms of the Swedish military. He defeated, in separate wars, Denmark, Poland, and Russia, gaining from the latter two the provinces of Ingria and Livonia. He embarked upon his greatest campaign through Germany, from 1630 to his death at the Battle of Lützen in 1632, during the Thirty Years’ War. Though Gustavus’ achievements against Denmark, Russia, and Poland did much in establishing a Swedish Baltic empire, it was his exploits during the Thirty Years’ War that has drawn the most attention among historians. It was in the Thirty Years’ War that Sweden came to be directly involved in the dealings of the rest of Europe, breaking from its usual preference for staying in the periphery. It was through this involved action that Sweden gained its place among the great powers of Europe. There is much to be said by historians on the military endeavors of Gustavus Adolphus and his role in the Thirty Years’ War. An overwhelming majority of the studies on Gustavus Adolphus in the Thirty Years’ War have been written in German, Swedish, Danish, Russian, Polish, or numerous other European languages. -

Asin Indicate the Presence of the First Wave of the Hungarian Tribes

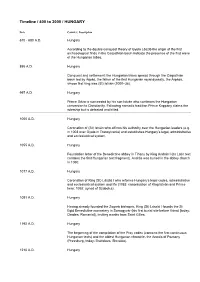

Timeline / 400 to 2000 / HUNGARY Date Country | Description 670 - 680 A.D. Hungary According to the double conquest theory of Gyula László the origin of the first archaeological finds in the Carpathian basin indicate the presence of the first wave of the Hungarian tribes. 895 A.D. Hungary Conquest and settlement: the Hungarian tribes spread through the Carpathian basin led by Árpád, the father of the first Hungarian royal dynasty, the Árpáds, whose first king was (St) István (1000–38). 997 A.D. Hungary Prince Géza is succeeded by his son István who continues the Hungarian conversion to Christianity. Following nomadic tradition Prince Koppány claims the rulership but is defeated and killed. 1000 A.D. Hungary Coronation of (St) István who affirms his authority over the Hungarian leaders (e.g. in 1003 over Gyula in Transylvania) and establishes Hungary’s legal, administrative and ecclesiastical system. 1055 A.D. Hungary Foundation letter of the Benedictine abbey in Tihany by King András I (its Latin text contains the first Hungarian text fragment). András was buried in the abbey church in 1060. 1077 A.D. Hungary Coronation of King (St) László I who reforms Hungary’s legal codes, administrative and ecclesiastical system and life (1083: canonisation of King István and Prince Imre; 1092: synod of Szabolcs). 1091 A.D. Hungary Having already founded the Zagreb bishopric, King (St) László I founds the St Egid Benedictine monastery in Somogyvár (his first burial site before Várad [today: Oradea, Romania]), inviting monks from Saint Gilles. 1192 A.D. Hungary The beginning of the compilation of the Pray codex (contains the first continuous Hungarian texts) and the oldest Hungarian chronicle, the Annals of Pozsony (Pressburg, today: Bratislava, Slovakia). -

A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699

A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699 Edited by Gábor Almási, Szymon Brzezi ski, Ildikó Horn, Kees Teszelszky and Áron Zarnóczki Volume 2 Diplomacy, Information Flow and Cultural Exchange Edited by Szymon Brzezi ski and Áron Zarnóczki A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699; Volume 2 Diplomacy, Information Flow and Cultural Exchange, Edited by Szymon Brzezi ski and Áron Zarnóczki This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Szymon Brzezi ski, Áron Zarnóczki and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6687-3, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6687-3 CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Zone of ConflictZone of Exchange: Introductory Remarks on Early Modern Hungary in Diplomatic and Information Networks ....................... 1 Szymon Brzezi ski I. Hungary and Transylvania in the Early Modern Diplomatic and Information Networks Re-Orienting a Renaissance Diplomatic Cause Célèbre: The 1541 Rincón-Fregoso Affair .............................................................. -

General Historical Survey

General Historical Survey 1521-1525 tention to the Knights Hospitallers on Rhodes (which capitulated late During the later years of his reign Sultan Selīm I was engaged militar- in 1522 after a long siege). ily against the Safavid state in Iran and the Mamluk sultanate in Syria and Egypt, so Central Europe felt relatively safe. King Lajos II of Hun- gary was only ten years old when, in 1516, he succeeded to the throne 1526-1530 and was placed under guardianship. In 1506 he had already been be- Between 1523 and 1525 Süleyman and his Grand Vizier and favour- trothed to Maria, the sister of Emperor Ferdinand, by the Pact of Wie- ite, Ibrahim Pasha (d. 942/1536), were chiefly engaged in settling ner Neustadt, where a royal double marriage was arranged between the affairs of Egypt. His second campaign into Hungary, which was the Habsburg and Jagiello dynasties. The government of Hungary was launched in April 1526, led ultimately, after a slow and difficult march, entrusted to a State Council, a group of men who were interested only to a military encounter known as the first Battle of Mohács. It was in enriching themselves. In a word: the crown had been reduced to fought on 20 Zilkade 932/29 August 1526 on the plain of Mohács, west political insignificance; the country was in chaos, the treasury empty, of the Danube in southern Hungary, near the present-day intersection the army virtually non-existent and the system of defence utterly ne- of Hungary, Croatia and Serbia. Both Süleyman and Lajos II partic- glected.