Download Complete File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All Rights Reserved. Do Not Share. STUDIES in HUNGARIAN HISTORY László Borhi, Editor

HUNGARY BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES 1526–1711 Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All rights reserved. Do not share. STUDIES IN HUNGARIAN HISTORY László Borhi, editor Top Left: Ferdinand I of Habsburg, Hungarian- Bohemian king (1526–1564), Holy Roman emperor (1558–1564). Unknown painter, after Jan Cornelis Vermeyen, circa 1530 (Hungarian National Museum, Budapest). Top Right: Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (1520–1566). Unknown painter, after Titian, sixteenth century (Hungarian National Museum, Budapest). Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All rights reserved. Do not share. Left: The Habsburg siege of Buda, 1541. Woodcut by Erhardt Schön, 1541 (Hungarian National Museum, Budapest). STUDIES IN HUNGARIAN HISTORY László Borhi, editor Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All rights reserved. Do not share. Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All rights reserved. Do not share. HUNGARY BETWEEN TWO EMPIR ES 1526–1711 Géza Pálffy Translated by David Robert Evans Indiana University Press Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All rights reserved. Do not share. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press Office of Scholarly Publishing Herman B Wells Library 350 1320 East 10th Street Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA iupress . org This book was produced under the auspices of the Research Center for the Humanities of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and with the support of the National Bank of Hungary. © 2021 by Géza Pálffy All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

The Battle of Christians and Ottomans in the Southwest of Bačka from the Battle of Mohács to the Peace of Zsitvatorok

doi: 10.19090/i.2017.28.86-104 UDC: 94(497):355.48(497.127 Mohács) ISTRAŽIVANJA ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPER JOURNAL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCHES Received: 13 May 2017 28 (2017) Accepted: 27 August 2017 ATTILA PFEIFFER University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Philosophy, Department of History [email protected] THE BATTLE OF CHRISTIANS AND OTTOMANS IN THE SOUTHWEST OF BAČKA FROM THE BATTLE OF MOHÁCS TO THE PEACE OF ZSITVATOROK Abstract: After the battle of Mohács in 1526 the medieval kingdom of Hungary was torn into three parts. The middle part from Buda to Belgrade was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. These territories suffered much in the 16th century because of the wars between the Habsburgs and the Ottoman Turks. Therefore, we do not have many historical resources from this period. The territory of South Bačka was a war zone many times from 1526 to 1606, where the Habsburgs, Hungarians and Ottoman Turks fought many battles. The aim of this study is to represent these struggles between Christians and Muslim Turks, focusing on the territories of the early modern Counties of Bač and Bodrog. Moreover, we are going to analyse the consequences of these wars for the population and economy of the mentioned counties. Keywords: early modern period, Ottoman Hungary, Counties of Bač and Bodrog, fortress of Bač, Turkish wars, military history. fter the defeat of the Hungarian army on the field of Mohács (29 August 1526), Hungary went through perhaps the worst period in its history. Simultaneously it A had to fight against the conquerors and in the meantime, the issue of the heir to the throne was raised because of the death of king Lajos II (1516-1526) in the battle of Mohács. -

The Hungarian Historical Review “Continuities and Discontinuities

The Hungarian Historical Review New Series of Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae Volume 5 No. 1 2016 “Continuities and Discontinuities: Political Thought in the Habsburg Empire in the Long Nineteenth Century” Ferenc Hörcher and Kálmán Pócza Special Editors of the Thematic Issue Contents Articles MARTYN RADY Nonnisi in sensu legum? Decree and Rendelet in Hungary (1790–1914) 5 FERENC HÖRCHER Enlightened Reform or National Reform? The Continuity Debate about the Hu ngarian Reform Era and the Example of the Two Széchenyis (1790–1848) 22 ÁRON KOVÁCS Continuity and Discontinuity in Transylvanian Romanian Thought: An Analysis of Four Bishopric Pleas from the Period between 1791 and 1842 46 VLASTA ŠVOGER Political Rights and Freedoms in the Croatian National Revival and the Croatian Political Movement of 1848–1849: Reestablishing Continuity 73 SARA LAGI Georg Jellinek, a Liberal Political Thinker against Despotic Rule (1885–1898) 105 ANDRÁS CIEGER National Identity and Constitutional Patriotism in the Context of Modern Hungarian History: An Overview 123 http://www.hunghist.org HHHR_2016_1.indbHR_2016_1.indb 1 22016.06.03.016.06.03. 112:39:582:39:58 Contents Book Reviews Das Preßburger Protocollum Testamentorum 1410 (1427)–1529, Vol. 1. 1410–1487. Edited by Judit Majorossy and Katalin Szende. Das Preßburger Protocollum Testamentorum 1410 (1427)–1529, Vol. 2. 1487–1529. Edited by Judit Majorossy und Katalin Szende. Reviewed by Elisabeth Gruber 151 Sopron. Edited by Ferenc Jankó, József Kücsán, and Katalin Szende with contributions by Dávid Ferenc, Károly Goda, and Melinda Kiss. Sátoraljaújhely. Edited by István Tringli. Szeged. Edited by László Blazovich et al. Reviewed by Anngret Simms 154 Egy székely két élete: Kövendi Székely Jakab pályafutása [Two lives of a Székely: The career of Jakab Székely of Kövend]. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta Making Magyars, Creating Hungary: András Fáy, István Bezerédj and Ödön Beöthy’s Reform-Era Contributions to the Development of Hungarian Civil Society by Eva Margaret Bodnar A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics © Eva Margaret Bodnar Spring 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract The relationship between magyarization and Hungarian civil society during the reform era of Hungarian history (1790-1848) is the subject of this dissertation. This thesis examines the cultural and political activities of three liberal oppositional nobles: András Fáy (1786-1864), István Bezerédj (1796-1856) and Ödön Beöthy (1796-1854). These three men were chosen as the basis of this study because of their commitment to a two- pronged approach to politics: they advocated greater cultural magyarization in the multiethnic Hungarian Kingdom and campaigned to extend the protection of the Hungarian constitution to segments of the non-aristocratic portion of the Hungarian population. -

The Hungarian Historical Review

Hungarian Historical Review 5, no. 1 (2016): 5–21 Martyn Rady Nonnisi in sensu legum? Decree and Rendelet in Hungary (1790–1914) The Hungarian “constitution” was never balanced, for its sovereigns possessed a supervisory jurisdiction that permitted them to legislate by decree, mainly by using patents and rescripts. Although the right to proceed by decree was seldom abused by Hungary’s Habsburg rulers, it permitted the monarch on occasion to impose reforms in defiance of the Diet. Attempts undertaken in the early 1790s to hem in the ruler’s power by making the written law both fixed and comprehensive were unsuccessful. After 1867, the right to legislate by decree was assumed by Hungary’s government, and ministerial decree or “rendelet” was used as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Not only could rendelets be used to fill in gaps in parliamentary legislation, they could also be used to bypass parliament and even to countermand parliamentary acts, sometimes at the expense of individual rights. The tendency remains in Hungary for its governments to use discretionary administrative instruments as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Keywords: constitution, decree, patent, rendelet, legislation, Diet, Parliament In 1792, the Transylvanian Diet opened in the assembly rooms of Kolozsvár (today Cluj, Romania) with a trio, sung by the three graces, each of whom embodied one of the three powers identified by Montesquieu as contributing to a balanced constitution.1 The Hungarian constitution, however, was never balanced. The power attached to the executive was always the greatest. Attempts to hem in the executive, however, proved unsuccessful. During the later nineteenth century, the legislature surrendered to ministers a large share of its legislative capacity, with the consequence that ministerial decree or rendelet often took the place of statute law. -

Hungary and the Habsburgs in the Early Modern Period

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION: HUNGARY AND THE HABSBURGS IN THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Prejudices and Debatable Interpretations The way in which the sixteenth and seventeenth cen- tury relations of the Habsburg Monarchy and the Kingdom of Hungary were viewed changed significantly after the first half of the nineteenth century. Modern Hungarian historiography came into existence in the eighteenth century. Its first practitioners were influenced by the con- temporary Habsburg state in which they lived. The appearance of the nation-states and of the concept of national independence brought major changes. The historical concept of independence became the major trend in Hungarian historiography during the last third of the nineteenth century. Its role is still important today and was particularly important during certain earlier periods. It was accepted equally by Catholic and Protestant historians, by positivists just as much as by the historians of ideas, by Marxists and by the partisans of the national romanticism of our day.1 A solid basis was laid down, during the second half of the nine- teenth century, by the romantic nationalist historians.2 They uncovered enormous archival material but assessed it from the perspective of the political situation and independist ideology of the times. The principal representatives of this approach were the Protestant Kálmán Thaly (1839–1909) and the leader of the Viennese research group, Sándor 2 THE KINGDOM OF HUNGARY AND THE HABSBURG MONARCHY Takáts (1860–1932), a Piarist priest. The former published a number of volumes of source material on the activities of Imre Thököly and Ferenc II Rákóczi but, as a leading member of the Independence Party, the concepts of national independence dominated his historiography. -

Nr. 3-4 Mai- August

ACADEMIA ROMANA INSTITUTUL DE ISTORIE "N. IORGA" REVISTA ISTORICA Fondator N. lorga :4.7-AFR .... a --..._ 4.11'g II /13II011IN- 4*741.1046:11 I a. -:.I --J 44. ,,, ;.- 'II:4. -\ rik. st:1 .. I t"'" -e.141'1,1.1.01,1 HYPgjill0140111111111 OW DWI Serienorth",Tomul XV, 2004 Nr. 3-4 mai- august www.dacoromanica.ro ACADEMIA ROMANA INSTITUTUL DE ISTORIE N. IORGA" COLEGIUL DE REDACTIE CORNELIA BODEA (redactor ef), IOAN SCURTU (redactor §ef adjunct). NAGY PIENARU (redactor responsabil), VENERA ACHIM (redactor) REVISTA ISTORICA" apare de 6 ori pe an. La revue REVISTA ISTORICA" parait 6 fois l'an. REVISTA ISTORICA" is published in six issues per year. REDACTIA: NAGY PIENARU (redactor responsabil) VENERA ACHIM (redactor) IOANA VOIA (traduccitor) Manuscrisele, cdrtilei revistele pentru schimb, precum §i mice corespondentd se vor trimite pe adresa redactiei revistei: REVISTA ISTORICA", B-dul Aviatorilor, nr. 1, 011851 - Bucure§ti, Tel. 212.88.90 E-mail: [email protected] www.dacoromanica.ro REVISTA ISTORICA SERIE NOUA TOMUL XV, NR. 34 Mai August 2004 SUMAR EPOCA LUI STEFAN CEL MARE $TEFAN ANDREESCU, Amintirea lui Stefan cel Mare in Tara Romaneasca 5-10 NICHITA ADANILOAIE, Spiru Haret initiatorul si organizatorul comemorarii lui Stefan cel Mare in 1904. 11-24 OVIDIU CR1STEA, Pacea din 1486 si relatiile lui Stefan cel Mare cu Imperiul otoman in ultima parte a domniei 25-36 EUGEN DENIZE, Moldova lui $tefan cel Mare la intersectia de interese a marilor puteri (1457-1474) 37-54 ION TURCANU, Conexiunile factorilor militari religios in politica externa a lui $tefan cel Mare . 55-66 LIVIU MARIUS ILIE, Stefan cel Mare si asocierea la tronul Moldovei 67-82 JUSTITIA LEGE $1 CUTUMA VIOLETA BARBU. -

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: the Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: The Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918 MICHAEL LAURENCE MILLER WO OF THE MOST ICONIC PHOTOS of the 1956 Hungarian revolution involve a colossal statue of Stalin, erected in 1951 and toppled on the first day of the anti-Soviet uprising. TOne of these pictures shows Stalin’s decapitated head, abandoned in the street as curious pedestrians amble by. The other shows a tall stone pedestal with nothing on it but a lonely pair of bronze boots. Situated near Heroes’ Square, Hungary’s national pantheon, the Stalin statue had served as a symbol of Hungary’s subjugation to the Soviet Union; and its ceremonious and deliberate destruction provided a poignant symbol for the fall of Stalinism. Thirty-eight years before, at the beginning of an earlier Hungarian revolution, another despised statue was toppled in Budapest, also marking a break from foreign subjugation, albeit to a different power. Unlike the Stalin statue, which stood for only five years, this statue—the so-called Hentzi Monument—had been “a splinter in the eye of the [Hungarian] nation” for sixty-six years. Perceived by many Hungarians as a symbol of “national humiliation” at the hands of the Habsburgs, the Hentzi Monument remained mired in controversy from its unveiling in 1852 until its destruction in 1918. The object of street demonstrations and parliamentary disorder in 1886, 1892, 1898, and 1899, and the object of a failed “assassination” attempt in 1895, the Hentzi Monument was even implicated in the fall of a Hungarian prime minister. -

The Hungarian Historical Review

Hungarian Historical Review 3, no. 4 (2014): 729–748 Zsófia Kádár The Difficulties of Conversion Non-Catholic Students in Jesuit Colleges in Western Hungary in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century The societies of the multiethnic and multilingual region of Central Europe became more diverse through the emergence of distinct confessions (Konfessionalisierung). The first half of the seventeenth century is especially interesting in this regard. In this period, the Catholic Church started to win back its positions in the Hungarian Kingdom as well, but the institutionalization of the Protestant denominations had by that time essentially reached completion. The schools, which were sustained by the various denominations, became the most efficient devices of religious education, persuasion and conversion. In this essay I present, through the example of the Jesuit colleges of western Hungary, the denominational proportions and movements of the students in the largely non-Catholic urban settings. Examining two basic types of sources, the annual accounts (Litterae Annuae) of the Society of Jesus and the registries of the Jesuit colleges in Győr and Pozsony (today Bratislava, Slovakia), I compare and contrast the data and venture an answer to questions regarding the kinds of opportunities non- Catholic students had in the Jesuit colleges. In contrast with the assertions made in earlier historiography, I conclude that conversion was not so widespread in the case of the non-Catholic students of the Jesuits. They were not discriminated against in their education, and some of them remained true to their confessions to the end of their studies in the colleges. Keywords: conversion, Jesuit colleges, school registries, annual accounts (Litterae Annuae), denominations in towns, urban history, Hungary, Győr, Pozsony, Pressburg, Bratislava, Sopron A student, the son of a soldier or a burgher, took leave of Calvinism, an act with which he completely infuriated his parents, so much so that his father planned to kill him. -

With Or Without Estates? Governorship in Hungary in the Eighteenth Century Krisztina Kulcsár National Archives of Hungary [email protected]

Hungarian Historical Review 10, no. 1 (2021): 96–128 With or without Estates? Governorship in Hungary in the Eighteenth Century Krisztina Kulcsár National Archives of Hungary [email protected] In the eighteenth century, the Hungarian estates had the greatest influence among the estates of the provinces of the Habsburg Monarchy. The main representative of the estates was the palatine, appointed by the monarch but elected by the estates at the Diet. He performed substantial judicial, administrative, financial, and military tasks in the Kingdom of Hungary. After 1526, the Habsburg sovereigns opted to rule the country on several occasions through governors who were appointed precisely because of the broad influence of the palatine. In this essay, I examine the reasons why the politically strong Hungarian estates in the eighteenth century accepted the appointment of governors instead of a palatine. I also consider what the rights and duties of these governors were, the extent to which these rights and duties differed from those of the palatine, and what changes they went through in the early modern period. I show how the idea and practice of appointing archdukes as governors or palatines was conceived and evolved at the end of the eighteenth century. The circumstances of these appointments of Francis Stephen of Lorraine, future son-in-law of Charles VI, Prince Albert of Saxony(-Teschen), future son-in-law of Maria Theresa and Archduke Joseph, shed light on considerations and interests which lay in the background of the compromises and political bargains made between the Habsburg(-Lorraine) rulers and the Hungarian estates. -

Medical Provision in the Convents of Poor Clares in Late-Eighteenth-Century Hungary Katalin Pataki

Medical Provision in the Convents of Poor Clares in Late-eighteenth-century Hungary Katalin Pataki To cite this version: Katalin Pataki. Medical Provision in the Convents of Poor Clares in Late-eighteenth-century Hungary. Cornova, the Czech Society for Eighteenth Century Studies, 2016, 6 (2), pp.33-58. halshs-01534725 HAL Id: halshs-01534725 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01534725 Submitted on 8 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License cornova 6 (2/2016) Katalin Pataki Medical Provision in the Convents of Poor Clares in Late- eighteenth-century Hungary* ▨ Abstract: The article sets into focus the everyday practices of caring the sick in the Poor Clares’ convents of Bratislava, Trnava, Zagreb, Buda and Pest with a time scope focused on the era of Maria Theresa’s and Joseph II’s church reforms. It evinces that each convent had an infirmary, in which the ill nuns could be separated from the rest of the community and nursed according to the instructions of a doctor, but the investigation of the rooms and their equipment also reveals significant differences among them. -

Asin Indicate the Presence of the First Wave of the Hungarian Tribes

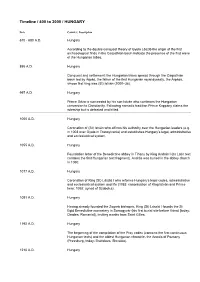

Timeline / 400 to 2000 / HUNGARY Date Country | Description 670 - 680 A.D. Hungary According to the double conquest theory of Gyula László the origin of the first archaeological finds in the Carpathian basin indicate the presence of the first wave of the Hungarian tribes. 895 A.D. Hungary Conquest and settlement: the Hungarian tribes spread through the Carpathian basin led by Árpád, the father of the first Hungarian royal dynasty, the Árpáds, whose first king was (St) István (1000–38). 997 A.D. Hungary Prince Géza is succeeded by his son István who continues the Hungarian conversion to Christianity. Following nomadic tradition Prince Koppány claims the rulership but is defeated and killed. 1000 A.D. Hungary Coronation of (St) István who affirms his authority over the Hungarian leaders (e.g. in 1003 over Gyula in Transylvania) and establishes Hungary’s legal, administrative and ecclesiastical system. 1055 A.D. Hungary Foundation letter of the Benedictine abbey in Tihany by King András I (its Latin text contains the first Hungarian text fragment). András was buried in the abbey church in 1060. 1077 A.D. Hungary Coronation of King (St) László I who reforms Hungary’s legal codes, administrative and ecclesiastical system and life (1083: canonisation of King István and Prince Imre; 1092: synod of Szabolcs). 1091 A.D. Hungary Having already founded the Zagreb bishopric, King (St) László I founds the St Egid Benedictine monastery in Somogyvár (his first burial site before Várad [today: Oradea, Romania]), inviting monks from Saint Gilles. 1192 A.D. Hungary The beginning of the compilation of the Pray codex (contains the first continuous Hungarian texts) and the oldest Hungarian chronicle, the Annals of Pozsony (Pressburg, today: Bratislava, Slovakia).