Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Berlin, Den 17.12.2002 Jürgen-Fuchs-Straße in Erfurt Am

Berlin, den 17.12.2002 Jürgen-Fuchs-Straße in Erfurt Am 20. Dezember 02, anläßlich des 52. Geburtstags des Dichters, wird die Straße am Landtag in Erfurt in Jürgen-Fuchs-Straße benannt. Die Stadt Erfurt und der Landtag des Landes Thüringen ehren mit der Benennung einen Poeten, der mit seinen intensiven, leisen Gedichten die Nöte einer DDR-Jugend ausdrückte, die sich in den Zwängen des totalen Anspruches der SED auf die Menschen selbst zu behaupten versuchte. Seine akribische Beobachtung wertete die Realität ohne den erhobenen Zeigefinger des Moralisten. Die real existierenden Sozialisten sperrten ihn dafür ins Gefängnis und schoben ihn vor 25 Jahren in den Westen ab. Der so in eine neue Welt Geworfene konnte nun in seinem Beruf als Psychologe arbeiten und baute gemeinsam mit seiner Frau den "Treffpunkt Waldstraße" im Berliner Problembezirk Moabit auf, einen Heimatort für Jugendliche und Kinder aus schwierigen sozialen Verhältnissen.Jürgen Fuchs' literarisches Werk blieb nicht bei der Beschreibung des sozialistischen Totalitarismus stehen, sondern lotete die Möglichkeiten des Menschseins darin aus. In seiner Geradlinigkeit und seinem unbestechlichen Urteil achtete Fuchs darauf, daß die Aufarbeitung des SED-Unrechts nicht abstrakt blieb, sondern den Menschen in ihrer konkreten Situation gerecht wurde. Dafür ist ihm das Bürgerbüro e.V., zu dessen Gründern er gehörte, dankbar und verpflichtet. Der Weg in den Thüringer Landtag führt zukünftig über eine Straße der Sensibilität für die Nöte der Mitmenschen und des Engagements für die Menschenrechte. Dr. Ehrhart Neubert, amt. Vorsitzender Ralf Hirsch, Vorstand Presseerklärung vom 22.10.2002 JÖRN MOTHES: Kein Abstand zur Diktatur Ringstorff und Holter haben in ihrer Koalitionsvereinbarung die Auflösung der Behörde des Landesbeauftragten des Landes Mecklenburg-Vorpommern für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen DDR beschlossen. -

Remembering East German Childhood in Post-Wende Life Narratives" (2013)

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2013 Remembering East German Childhood In Post- Wende Life Narratives Juliana Mamou Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mamou, Juliana, "Remembering East German Childhood In Post-Wende Life Narratives" (2013). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 735. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. REMEMBERING EAST GERMAN CHILDHOOD IN POST-WENDE LIFE NARRATIVES by JULIANA MAMOU DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2013 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: _____________________________________ Advisor Date _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY JULIANA MAMOU 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my great appreciation to the members of my Dissertation Committee, Professor Donald Haase, Professor Lisabeth Hock, and Professor Anca Vlasopolos, for their constructive input, their patience, and support. I am particularly grateful for the assistance -

The GDR Opposition Archive

The GDR Opposition Archive in the Robert Havemann Society The GDR Opposition Archive in the Robert Havemann Society holds the largest accessible collection of testaments to the protest against the SED dictatorship. Some 750 linear metres of written material, 180,000 photos, 5,000 videos, 1,000 audio cassettes, original banners and objects from the years 1945 to 1990 all provide impressive evidence that there was always contradiction and resistance in East Germany. The collection forms a counterpoint and an important addition to the version of history presented by the former regime, particularly the Stasi files. Originally emerging from the GDR’s civil rights movement, the archive is now known beyond Germany itself. Enquiries come from all over Europe, the US, Canada, Australia and Korea. Hundreds of research papers, radio and TV programmes, films and exhibitions on the GDR have drawn on sources from the collection. Thus, the GDR Opposition Archive has made a key contribution to our understanding of the communist dictatorship. Testimonials on opposition and resistance against the communist dictatorship The GDR Opposition Archive is run by the Robert Havemann Society. It was founded 26 years ago, on 19 November 1990, by members and supporters of the New Forum group, including prominent GDR opposition figures such as Bärbel Bohley, Jens Reich, Sebastian Pflugbeil and Katja Havemann. To this day, the organisation aims to document the history of opposition and resistance in the GDR and to ensure it is not forgotten. The Robert Havemann Society has been funded entirely on a project basis since its foundation. Its most important funding institutions include the Berlin Commissioner for the Stasi Records and the Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship. -

Freya Klier (Sender Freies Berlin, Berlin, Juli 2001 September 2001) „ DIE DRITTEN DEUTSCHEN“ 1. Momentaufnahme Eine

Freya Klier (Sender Freies Berlin, Berlin, Juli 2001 September 2001) „ DIE DRITTEN DEUTSCHEN“ 1. Momentaufnahme einer Fluchtwelle Im „Askanischen Gymnasium“ Berlin-Tempelhof richtet der amtierende Direktor zwei sogenannte „Ost-Klassen“ ein. Wir schreiben das Jahr 1957 - noch trennt die Deutschen keine Mauer. Doch gibt es in der DDR bereits eine große Zahl Jugendlicher, denen aus politischen Gründen das Abitur verwehrt wird: Schon verhaltene Kritik an der SED und ihrem Jugendverband FDJ oder ein Engagement in der Kirche reichen, um von höherer Bildung ausgeschlossen zu sein. Etliche Jugendliche aus Ostberlin und Umgebung nutzen also vor dem Mauerbau die Chance, in Westberlin das Abitur abzulegen - einige schleichen in täglicher Nervenbelastung über die Zonengrenze, andere sind vor Ort untergebracht, bei der Heilsarmee oder im Kloster zum Guten Hirten, und kehren nur am Wochenende heim zu ihren Familien. Der Direktor, auf der Suche nach einem Ausweg aus dem Dilemma ostdeutscher Bildungsverbote, ist selbst ein Zonenflüchtling und kennt sich in der Materie aus. Das Lehrerkollegium des „Askanischen Gymnasiums“ aber beweist Mut mit seinen Ostklassen, denn das SED-Regime rächt sich, die Lehrer werden bei Kollegiumsfahrten von DDR-Grenzern stets besonders schikaniert. Für die Schüler aus dem Osten aber eröffnet sich sesamgleich die Welt der Demokratie - sie werden in den Diskurs über Europa involviert, die jüdische Geschichte, die Deutschlandfrage... Die meisten der 280 Ost-Schüler, die im Lauf von fünf Jahren in Westberlin das Abitur ablegen, werden früher oder später für immer im westlichen Teil Deutschlands landen. Sie sind Teil einer riesigen Fluchtwelle, die vor 1989 stets in die gleiche Richtung rollt - von Ost nach West. -

The Divided Nation a History of Germany 19181990

Page iii The Divided Nation A History of Germany 19181990 Mary Fulbrook Page 318 Thirteen The East German Revolution and the End of the Post-War Era In 1989, Eastern Europe was shaken by a series of revolutions, starting in Poland and Hungary, spreading to the GDR and then Czechoslovakia, ultimately even toppling the Romanian communist regime, and heralding the end of the post-war settlement of European and world affairs. Central to the ending of the post-war era were events in Germany. The East German revolution of 1989 inaugurated a process which only a few months earlier would have seemed quite unimaginable: the dismantling of the Iron Curtain between the two Germanies, the destruction of the Berlin Wall, the unification of the two Germanies. How did such dramatic changes come about, and what explains the unique pattern of developments? To start with, it is worth reconsidering certain features of East Germany's history up until the 1980s. The uprising of 1953 was the only previous moment of serious political unrest in the GDR. It was, as we have seen above, limited in its origins and initial aims-arising out of a protest by workers against a rise in work norms-and only developed into a wider phenomenon, with political demands for the toppling of Ulbricht and reunification with West Germany, as the protests gained momentum. Lacking in leadership, lacking in support from the West, and ultimately repressed by a display of Soviet force, the 1953 uprising was a short-lived phenomenon. From the suppression of the 1953 revolt until the mid-1980s, the GDR was a relatively stable communist state, which gained the reputation of being Moscow's loyal ally, communism effected with Prussian efficiency. -

REFORM, RESISTANCE and REVOLUTION in the OTHER GERMANY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository RETHINKING THE GDR OPPOSITION: REFORM, RESISTANCE AND REVOLUTION IN THE OTHER GERMANY by ALEXANDER D. BROWN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music University of Birmingham January 2019 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The following thesis looks at the subject of communist-oriented opposition in the GDR. More specifically, it considers how this phenomenon has been reconstructed in the state-mandated memory landscape of the Federal Republic of Germany since unification in 1990. It does so by presenting three case studies of particular representative value. The first looks at the former member of the Politbüro Paul Merker and how his entanglement in questions surrounding antifascism and antisemitism in the 1950s has become a significant trope in narratives of national (de-)legitimisation since 1990. The second delves into the phenomenon of the dissident through the aperture of prominent singer-songwriter, Wolf Biermann, who was famously exiled in 1976. -

Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle William D

History Faculty Publications History 11-7-2014 Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle William D. Bowman Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac Part of the Cultural History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, Eastern European Studies Commons, European History Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Bowman, William D. "Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle." Philly.com (November 7, 2014). This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac/53 This open access opinion is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle Abstract When the Berlin Wall fell 25 years ago, on Nov. 9, 1989, symbolically signaling the end of the Cold War, it was no surprise that many credited President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev for bringing it down. But the true heroes behind the fall of the Berlin Wall are those Eastern Europeans whose protests and political pressure started chipping away at the wall years before. East -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. We use the term “state socialism” in the title of and introduction to this book to refer to the type of political, economic, and social welfare system that existed in postwar Eastern Europe. This was different from the social democracy practiced by some Western European democracies, which, while providing social services and benefits to the population did not advocate the complete overthrow of the market economy and the leading role of one political party. At the same time, since the parties in power during this period identified as communist and because policymakers, scholars, and people of the region often employ the term “communist” or “socialist” when referring to the system (political, economic, and/or social welfare) that existed in postwar Eastern Europe, we recognize the validity of using these terms. 2. See, for example, Nanette Funk and Magda Mueller, eds., Gender Politics and Post-Communism: Reflections from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union (New York, 1993); Barbara Einhorn, Cinderella Goes to Market: Citizenship, Gender and Women’s Movements in East Central Europe (London, 1993); Chris Corrin, ed., Superwomen and the Double Burden: Women’s Experiences of Change in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union (New York, 1993); Marilyn Rueschemeyer, ed., Women in the Politics of Postcommunist Eastern Europe (Armonk, 1994); Barbara Lobodziknska, ed. Family, Women, and Employment in Central- Eastern Europe (Westport, 1995); Susan Gal and Gail Kligman, eds., Reproducing Gender: Politics, Publics, and Everyday Life after Socialism (Princeton, 2000); Susan Gal and Gail Kligman, eds., The Politics of Gender After Socialism: A Comparative-Historical Essay (Princeton, 2002); Kristen Ghodsee, Red Riviera: Gender, Tourism, and Postsocialism on the Black Sea (Durham, NC, 2005); Jasmina Lukic´, Joanna Regulska, and Darja Zaviršek, eds., Women and Citizenship in Central and Eastern Europe (Aldershot, UK, 2006); and Janet E. -

Drucksache 13/10893 29. 05. 98

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 13/10893 13. Wahlperiode 29. 05. 98 Bericht des Ausschusses für Wahlprüfung, Immunität und Geschäftsordnung (1. Ausschuß) zu dem Überprüfungsverfahren des Abgeordneten Dr. Gregor Gysi gemäß § 44 b Abs. 2 Abgeordnetengesetz (Überprüfung auf eine Tätigkeit oder eine politische Verantwortung für das Ministerium für Staatssicherheit/Amt für Nationale Sicherheit der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik) Gliederung Seite 1. Feststellung des Prüfungsergebnisses 3 2. Rechtsgrundlagen des Überprüfungsverfahrens 3 2.1 § 44 b des Abgeordnetengesetzes 3 2.2 Richtlinien 3 2.3 Absprache zur Durchführung der Richtlinien gemäß § 44 b AbgG 3 2.4 Entscheidung des Bundesverfassungsgerichts 4 3. Ablauf des Überprüfungsverfahrens 4 3.1 12. Wahlperiode 4 3.2 13. Wahlperiode 5 4. Grundlagen der Überprüfung des Abg. Dr. Gysi 6 4.1 Zum Quellenwert der Unterlagen des MfS 6 4.2 Recherchen des Bundesbeauftragten mit Bezug auf Dr. Gysi 7 5. Staatliche Kontrolle der politischen Opposition in der DDR 9 5.1 Bekämpfung der politischen Opposi tion durch das MfS 9 5.2 Zur Rolle der Staatsanwaltschaft in MfS-Verfahren 10 5.3 Einfluß der SED 10 6. Einzelfälle der Zusammenarbeit Dr. Gysis mit dem MfS 11 6.1 Rudolf Bahro 11 6.1.1 Die Übernahme der anwaltlichen Vertretung 11 6.1.2 Das Testament Rudolf Bahros 12 6.1.3 Notizen Rudolf Bahros im Zusammenhang mit der Veröffentlichung eines Briefes im „Spiegel" 13 Drucksache 13/10893 Deutscher Bundestag — 13. Wahlperiode Seite 6.1.4 Bestellter Brief 16 6.1.5 Haftbedingungen Rudolf Bahros/Vorschläge gegen den „Veröffentli rieb" -chungst17 6.1.6 Anruf aus West-Berlin 20 6.1.7 Zusammenfassung 20 6.2 Robert Havemann 20 6.2.1 Die Übernahme der anwaltlichen Vertretung 20 6.2.2 Die Eingabe an das MdI vom 20. -

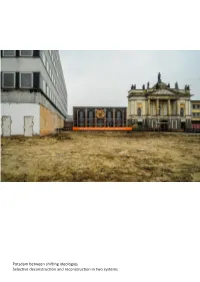

Potsdam Between Shifting Ideologies Selective Deconstruction And

Potsdam between shifting ideologies Selective deconstruction and reconstruction in two systems Architectural History Thesis TU Delft AR2A011 2020 / 2021 Q3 Frederic Hormesch 5147298 Cover: [Computer centre on the left, Marstall on the right, the Chapel of Reconciliation in the centre. Here the Garnisonkirche is being reconstructed]. (2016). https://digitalcosmonaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/rechenzentrum-potsdam-germany-deutschland-ddr-garnisonskirche-baustelle-903x600.jpg Contents 04 1. Introduction 05 2. Political background and architectural conception of the GDR 2.1 Formation and fall of the GDR 2.2 Historiography and self-conception of the GDR 2.3 Architecture in the GDR: Between expression and fundamental needs 09 3. Urbicide and its consequences in former GDR territories 3.1 Urbicide in the GDR 3.2 Urbicide since the reunification 11 4. Potsdam between heritage and reorientation 4.1 Potsdam’s feudal heritage 4.2 Potsdam in the context of the GDR 4.3 Rebuilding gets started 4.4 New problems and political redirection 4.5 The reunification and the revival of opulence 16 5. Potsdam Alter Markt and Garnisonkirche – reflecting shifting ideologies 5.1 Stadtschloss during the GDR 5.2 Reconstruction of the Stadtschloss 5.3 Garnisonkirche during the GDR 5.4 Reconstruction of the Garnisonkirche 24 6. Conclusion 26 References 28 llustrations 1. Introduction This paper examines how the political and ideological background of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) influenced architecture and urban planning, as well as the upswing of selective reconstruction and demolition in the former GDR following the German reunification. The thesis departs from the hypothesis that the frequent change of political and economic systems in post-war Germany was accompanied by an urbicide of architectural heritage and the selective use of historical legacy to satisfy their ideological demands. -

Nonviolent Struggle and the Revolution in East Germany

Nonviolent Struggle and the Revolution in East Germany Nonviolent Struggle and the Revolution in East Germany Roland Bleiker Monograph Series Number 6 The Albert Einstein Institution Copyright 01993 by Roland Bleiker Printed in the United States of America. Printed on Recycled Paper. The Albert Einstein Institution 1430 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 ISSN 1052-1054 ISBN 1-880813-07-6 CONTENTS Acknowledgments ................... .... ... .. .... ........... .. .. .................. .. .. ... vii Introduction ..............................................................................................1 Chapter 1 A BRIEF HISTORY OF DOMINATION, OPPOSITION, AND REVOLUTION IN EAST GERMANY .............................................. 5 Repression and Dissent before the 1980s...................................... 6 Mass Protests and the Revolution of 1989 .................................... 7 Chapter 2 THE POWER-DEVOLVING POTENTIAL OF NONVIOLENT S"I'RUGGLE................................................................ 10 Draining the System's Energy: The Role of "Exit" ...................... 10 Displaying the Will for Change: The Role of "Voice" ................ 13 Voluntary Servitude and the Power of Agency: Some Theoretical Reflections ..................................................15 Chapter 3 THE MEDIATION OF NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE: COMPLEX POWER RELATIONSHIPS AND THE ENGINEERING OF HEGEMONIC CONSENT ................................21 The Multiple Faces of the SED Power Base ..................................21 Defending Civil