Before the Iowa Supreme Court

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

False Dilemma Wikipedia Contents

False dilemma Wikipedia Contents 1 False dilemma 1 1.1 Examples ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Morton's fork ......................................... 1 1.1.2 False choice .......................................... 2 1.1.3 Black-and-white thinking ................................... 2 1.2 See also ................................................ 2 1.3 References ............................................... 3 1.4 External links ............................................. 3 2 Affirmative action 4 2.1 Origins ................................................. 4 2.2 Women ................................................ 4 2.3 Quotas ................................................. 5 2.4 National approaches .......................................... 5 2.4.1 Africa ............................................ 5 2.4.2 Asia .............................................. 7 2.4.3 Europe ............................................ 8 2.4.4 North America ........................................ 10 2.4.5 Oceania ............................................ 11 2.4.6 South America ........................................ 11 2.5 International organizations ...................................... 11 2.5.1 United Nations ........................................ 12 2.6 Support ................................................ 12 2.6.1 Polls .............................................. 12 2.7 Criticism ............................................... 12 2.7.1 Mismatching ......................................... 13 2.8 See also -

Forensic Pattern Recognition Evidence an Educational Module

Forensic Pattern Recognition Evidence An Educational Module Prepared by Simon A. Cole Professor, Department of Criminology, Law, and Society Director, Newkirk Center for Science and Society University of California, Irvine Alyse Berthental PhD Candidate, Department of Criminology, Law, and Society University of California, Irvine Jaclyn Seelagy Scholar, PULSE (Program on Understanding Law, Science, and Evidence) University of California, Los Angeles School of Law For Committee on Preparing the Next Generation of Policy Makers for Science-Based Decisions Committee on Science, Technology, and Law June 2016 The copyright in this module is owned by the authors of the module, and may be used subject to the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Public License. By using or further adapting the educational module, you agree to comply with the terms of the license. The educational module is solely the product of the authors and others that have added modifications and is not necessarily endorsed or adopted by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine or the sponsors of this activity. Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 Goals and Methods ..................................................................................................................... 1 Audience ..................................................................................................................................... -

Yesterday's Algorithm: Penrose on the Gödel Argument

Yesterday’s Algorithm: Penrose and the Gödel Argument §1. The Gödel Argument. Roger Penrose is justly famous for his work in physics and mathematics but he is notorious for his endorsement of the Gödel argument (see his 1989, 1994, 1997). This argument, first advanced by J. R. Lucas (in 1961), attempts to show that Gödel’s (first) incompleteness theorem can be seen to reveal that the human mind transcends all algorithmic models of it1. Penrose's version of the argument has been seen to fall victim to the original objections raised against Lucas (see Boolos (1990) and for a particularly intemperate review, Putnam (1994)). Yet I believe that more can and should be said about the argument. Only a brief review is necessary here although I wish to present the argument in a somewhat peculiar form. Let us suppose that the human cognitive abilities that underlie our propensities to acquire mathematical beliefs on the basis of what we call proofs can be given a classical cognitive psychological or computational explanation (henceforth I will often use ‘belief’ as short for ‘belief on the basis of proof’). These propensities are of at least two types: the ability to appreciate chains of logical reasoning but also the ability to recognise ‘elementary proofs’ or, it would perhaps be better to say, elementary truths, such as if a = b and b = c then a = c, without any need or, often, any possibility of proof in the first sense. On this supposition, these propensities are the realization of a certain definite algorithm or program somehow implemented by the neural hardware of the brain. -

In Defence of a Princess Margaret Premise

Fabrice Pataut: “In Defence of a Princess Margaret Premise,” Introductory chapter to Truth, Objects, Infinity – New Perspectives on the Philosophy of Paul Benacerraf, Fabrice Pataut, editor. Springer International Publishing, Logic, Epistemology, and the Unity of Science, vol. 28, Switzerland, 2016, pp. xvii-xxxviii. ISBN 978-3-319-45978-3 ISSN 2214-9775 ISBN 978-3-319-45980-6 (eBook) ISSN 2214-9783 (electronic) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-45980-6 Library of Congress Control Number : 2016950889 © Springer International Publishing Swtizerland 2016 1 IN DEFENCE OF A PRINCESS MARGARET PREMISE Fabrice Pataut 1. Introductory remarks In their introduction to the volume Benacerraf and his Critics, Adam Morton and Stephen Stich remark that “[t]wo bits of methodology will stand out clearly in anyone who has talked philosophy with Paul Benacerraf”: (i) “[i]n philosophy you never prove anything; you just show its price,” and (ii) “[f]ormal arguments yield philosophical conclusions only with the help of hidden philosophical premises” (Morton and Stich 1996b: 5). The first bit will come to some as a disappointment and to others as a welcome display of suitable modesty. Frustration notwithstanding, the second bit suggests that, should one stick to modesty, one might after all prove something just in case one discloses the hidden premises of one’s chosen argument and pleads convincingly in their favor on independent grounds. I would like to argue that a philosophical premise may be uncovered — of the kind that Benacerraf has dubbed “Princess Margaret Premise” (PMP)1 — that helps us reach a philosophical conclusion to be drawn from an argument having a metamathematical result as one of its other premises, viz. -

A Searchable Bibliography of Fallacies – 2016

A Searchable Bibliography of Fallacies – 2016 HANS V. HANSEN Department of Philosophy University of Windsor Windsor, ON CANADA N9B 3P4 [email protected] CAMERON FIORET Department of Philosophy University of Guelph Guelph, ON CANADA N1G 2W1 [email protected] This bibliography of literature on the fallacies is intended to be a resource for argumentation theorists. It incorporates and sup- plements the material in the bibliography in Hansen and Pinto’s Fallacies: Classical and Contemporary Readings (1995), and now includes over 550 entries. The bibliography is here present- ed in electronic form which gives the researcher the advantage of being able to do a search by any word or phrase of interest. Moreover, all the entries have been classified under at least one of 45 categories indicated below. Using the code, entered as e.g., ‘[AM-E]’, one can select all the entries that have been des- ignated as being about the ambiguity fallacy, equivocation. Literature about fallacies falls into two broad classes. It is either about fallacies in general (fallacy theory, or views about fallacies) or about particular fallacies (e.g., equivocation, appeal to pity, etc.). The former category includes, among others, con- siderations of the importance of fallacies, the basis of fallacies, the teaching of fallacies, etc. These general views about fallacies often come from a particular theoretical orientation about how fallacies are best understood; for example, some view fallacies as epistemological mistakes, some as mistakes in disagreement resolution, others as frustrations of rhetorical practice and com- munication. Accordingly, we have attempted to classify the en- © Hans V. Hansen & Cameron Fioret. -

On Computer-Based Assessment of Mathematics

ON COMPUTER-BASED ASSESSMENT OF MATHEMATICS DANIEL ARTHUR PEAD, BA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2010 Abstract This work explores some issues arising from the widespread use of computer based assessment of Mathematics in primary and secondary education. In particular, it considers the potential of computer based assessment for testing “process skills” and “problem solving”. This is discussed through a case study of the World Class Tests project which set out to test problem solving skills. The study also considers how on-screen “eAssessment” differs from conventional paper tests and how transferring established assessment tasks to the new media might change their difficulty, or even alter what they assess. Once source of evidence is a detailed comparison of the paper and computer versions of a commercially published test – nferNelson's Progress in Maths - including a new analysis of the publisher's own equating study. The other major aspect of the work is a design research exercise which starts by analysing tasks from Mathematics GCSE papers and proceeds to design, implement and trial a computer-based system for delivering and marking similar styles of tasks. This produces a number of insights into the design challenges of computer-based assessment, and also raises some questions about the design assumptions behind the original paper tests. One unanticipated finding was that, unlike younger pupils, some GCSE candidates expressed doubts about the idea of a computer-based examination. The study concludes that implementing a Mathematics test on a computer involves detailed decisions requiring expertise in both assessment and software design, particularly in the case of richer tasks targeting process skills. -

Fantasy & Science Fiction V023n04

13th Anniversary ALL STAR THE MAGAZINE 0 E Fantasy FANTAiy and Science Fictio SCIENCE The Journey of Joenes fiCTION a new novel by ROBERT SHFCfCtfY A Kind of Artistry BRIAN W. ALDISS 6 There Was an Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe ROBERT F. YOUNG 28 24 Hours in a Princess’s Life> With 'Fe6gs DON WHITE 34 Inquest in Kansas {verse) ;/ HYACINTHE HILL 38 Measure My Love ' MILDRED CLINGERMAN 39 Science', Slow Burn ISAAC ASIMOV 52 Books AVRAM DAVIDSON 63 The Unfortunate Mr. Morlcy VANCE AANDAHL 68 Ferdinand Feghoot: LV GRENDEL BRIARTON 70 The Journey of Joenes {1st 6j 2 parts ) ROBERT SHECKLEY 71 ^ Editorial > /* 4 / • In this issue . Coming si/on 5 F&SE Marketplace ' 129 Cover by Ed Emsh {illustrating ^'The Journey of Joenes”) The Magasine of Fantasy and Sciffiice Fiction, Vclume 23, No. 4, Whole No. 137, Oct. 1962. P-ttblisked monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 40^ a copy. Annual subscription S4 50 in U. S. and Possessions, $5.00 in Canada and the Pan American Union; $5.50 m all other countries. Publicaiion office, IQ Ferry Street, Concord, N. //. Editorial and general mail should be sent to 347 East 53rd St., New York 22, N. Y. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N. H. Printed in U. S. A. © 2^62 by Mercury Press, Inc. Ail rights, including translations into other languages, reserved. Submissions mtist be accom- panied by stamped, self-addressed envelopes; the Publisher assumes no responsibility for return of unsolicited manuscripts. Joseph W. Forman, publisher Avram Davidson, executive editor Robert P. -

Observations on Sick Mathematics Andrew Aberdein

ESSAY 1 Observations on Sick Mathematics Andrew Aberdein And you claim to have discovered this . from observations on sick people? (Freud 1990: 13) This paper argues that new light may be shed on mathematical reason- ing in its non-pathological forms by careful observation of its patholo- gies. The first section explores the application to mathematics of recent work on fallacy theory, specifically the concept of an ‘argumentation scheme’: a characteristic pattern under which many similar inferential steps may be subsumed. Fallacies may then be understood as argumen- tation schemes used inappropriately. The next section demonstrates how some specific mathematical fallacies may be characterized in terms · Andrew Aberdein of argumentation schemes. The third section considers the phenomenon of correct answers which result from incorrect methods. This turns out to pose some deep questions concerning the nature of mathematical knowledge. In particular, it is argued that a satisfactory epistemology for mathematical practice must address the role of luck. Otherwise, we risk being unable to distinguish successful informal mathematical rea- soning from chance. We shall see that argumentation schemes may play a role in resolving this problem too.1 Mathematical errors occur in many different forms. In his classic short treatment of the topic, E.A. Maxwell distinguished the simple mistake, which may be caused by ‘a momentary aberration, a slip in writing, or the misreading of earlier work,’ from the howler, ‘an error which leads innocently to a correct result,’ and the fallacy, which ‘leads by guile to a wrong but plausible conclusion’ (Maxwell 1959: 9). We might gloss this preliminary typology of mathematical error as correlating the (in)correctness of the result to the (un)soundness of the method, as in Table 1. -

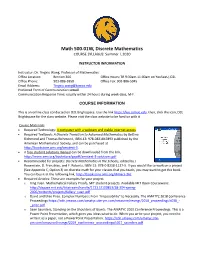

Math 500.01W, Discrete Mathematics COURSE SYLLABUS: Summer I, 2020

Math 500.01W, Discrete Mathematics COURSE SYLLABUS: Summer I, 2020 INSTRUCTOR INFORMATION Instructor: Dr. Tingxiu Wang, Professor of Mathematics Office Location: Binnion 306 Office Hours: TR 9:30am-11:00am on YouSeeU, D2L Office Phone: 903-886-5958 Office Fax: 903-886-5945 Email Address: [email protected] Preferred Form of Communication: email Communication Response Time: usually within 24 hours during week days, M-F. COURSE INFORMATION This is an online class conducted on D2L Brightspace. Use the link https://leo.tamuc.edu, then, click the icon, D2L Brightspace for the class website. Please visit the class website to be familiar with it. Course Materials: • Required Technology: A computer with a webcam and stable internet access. • Required Textbook: A Discrete Transition to Advanced Mathematics by Bettina Richmond and Thomas Richmond, ISBN-13: 978-0821847893 published by the American Mathematical Society, and can be purchased at http://bookstore.ams.org/amstext-3. • A free student solutions manual can be downloaded from the link, http://www.ams.org/bookstore/pspdf/amstext-3-solutions.pdf • Recommended for projects: Discrete Mathematics in the Schools, edited by J. Rosenstein, D. Franzblau, and F. Roberts, ISBN-13: 978-0-8218-1137-5. If you would like to work on a project (See Appendix C, Option 3) on discrete math for your classes that you teach, you may want to get this book. You can buy it at the following link, http://bookstore.ams.org/dimacs-36/. • Required Articles: These are examples for your project. o Xing Yuan. Mathematical Fallacy Proofs, MIT student projects. Available MIT Open Courseware: http://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/100853/18-304-spring- 2006/contents/projects/fallacy_yuan.pdf o David and Elise Price. -

Accepted Manuscript1.0

Nonlinear World – Journal of Interdisciplinary Nature Published by GVP – Prof. V. Lakshmikantham Institute for Advanced Studies and GVP College of Engineering (A) About Journal: Nonlinear World is published in association with International Federation of Nonlinear Analysts (IFNA), which promotes collaboration among various disciplines in the world community of nonlinear analysts. The journal welcomes all experimental, computational and/or theoretical advances in nonlinear phenomena, in any discipline – especially those that further our ability to analyse and solve the nonlinear problems that confront our complex world. Nonlinear World will feature papers which demonstrate multidisciplinary nature, preferably those presented in such a way that other nonlinear analysts can at least grasp the main results, techniques, and their potential applications. In addition to survey papers of an expository nature, the contributions will be original papers demonstrating the relevance of nonlinear techniques. Manuscripts should be submitted to: Dr. J Vasundhara Devi, Associate Director, GVP-LIAS, GVP College of Engineering (A), Madhurawada, Visakhapatnam – 530048 Email: [email protected] Subscription Information 2017: Volume 1 (1 Issue) USA, India Online Registration at www.nonlinearworld.com will be made available soon. c Copyright 2017 GVP-Prof. V. Lakshmikantham Insitute of Advanced Studies ISSN 0942-5608 Printed in India by GVP – Prof. V. Lakshmikantham Institute for Advanced Studies, India Contributions should be prepared in accordance with the ‘‘ Instructions for Authors} 1 Nonlinear World Honorary Editors Dr. Chris Tsokos President of IFNA, Executive Director of USOP, Editor in Chief, GJMS, IJMSM, IJES, IJMSBF Dr. S K Sen Director, GVP-LIAS, India Editor in Chief Dr. J Vasundhara Devi Dept. of Mathematics, GVPCE(A) and Associate Director, GVP-LIAS, India Editorial Board Dr. -

Science and Mathematics Education Centre

Science and Mathematics Education Centre Students’ Understanding of Evidence in Science through Studying Paradoxes and the Principle of Falsification Steven C. Lockwood This thesis is presented as part of the requirement of the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Curtin University of Technology February 2014 Declaration This thesis does not contain material accepted, in any university, for the award of any other degree or diploma. To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgement has been made. Signature: Date: 2 Acknowledgements To my wife Sue, and my children, Morgan, Darcy and Alec, (born during the long and protracted process of thesis generation and writing) I owe a debt of gratitude not least for their preparedness to excuse my absences from fatherly duties but also for their acceptance of my often irritating logical semantics, one of the side-effects of the study of paradox. A particular ‘thank you’ goes to Dr Bevis Yaxley (dec.) and Dr Roya Pugh whose contributions to my well-being during times of challenge, not the least of which occurred when my wife Sue died from breast cancer, afforded me the courage to persist where I may have resolved to give up. To my students, past and present, without whom I would not have written this thesis, particularly those students described admirably by the writer Jorge Luis Borges in his book Labyrinths which I paraphrase. …although I could expect nothing from those students who passively accepted my doctrines, I could of those who, at times, would venture a reasonable contradiction. -

List of Fallacies

List of fallacies For specific popular misconceptions, see List of common if>). The following fallacies involve inferences whose misconceptions. correctness is not guaranteed by the behavior of those log- ical connectives, and hence, which are not logically guar- A fallacy is an incorrect argument in logic and rhetoric anteed to yield true conclusions. Types of propositional fallacies: which undermines an argument’s logical validity or more generally an argument’s logical soundness. Fallacies are either formal fallacies or informal fallacies. • Affirming a disjunct – concluding that one disjunct of a logical disjunction must be false because the These are commonly used styles of argument in convinc- other disjunct is true; A or B; A, therefore not B.[8] ing people, where the focus is on communication and re- sults rather than the correctness of the logic, and may be • Affirming the consequent – the antecedent in an in- used whether the point being advanced is correct or not. dicative conditional is claimed to be true because the consequent is true; if A, then B; B, therefore A.[8] 1 Formal fallacies • Denying the antecedent – the consequent in an indicative conditional is claimed to be false because the antecedent is false; if A, then B; not A, therefore Main article: Formal fallacy not B.[8] A formal fallacy is an error in logic that can be seen in the argument’s form.[1] All formal fallacies are specific types 1.2 Quantification fallacies of non sequiturs. A quantification fallacy is an error in logic where the • Appeal to probability – is a statement that takes quantifiers of the premises are in contradiction to the something for granted because it would probably be quantifier of the conclusion.