A Searchable Bibliography of Fallacies – 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conjunction Fallacy' Revisited: How Intelligent Inferences Look Like Reasoning Errors

Journal of Behavioral Decision Making J. Behav. Dec. Making, 12: 275±305 (1999) The `Conjunction Fallacy' Revisited: How Intelligent Inferences Look Like Reasoning Errors RALPH HERTWIG* and GERD GIGERENZER Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT Findings in recent research on the `conjunction fallacy' have been taken as evid- ence that our minds are not designed to work by the rules of probability. This conclusion springs from the idea that norms should be content-blind Ð in the present case, the assumption that sound reasoning requires following the con- junction rule of probability theory. But content-blind norms overlook some of the intelligent ways in which humans deal with uncertainty, for instance, when drawing semantic and pragmatic inferences. In a series of studies, we ®rst show that people infer nonmathematical meanings of the polysemous term `probability' in the classic Linda conjunction problem. We then demonstrate that one can design contexts in which people infer mathematical meanings of the term and are therefore more likely to conform to the conjunction rule. Finally, we report evidence that the term `frequency' narrows the spectrum of possible interpreta- tions of `probability' down to its mathematical meanings, and that this fact Ð rather than the presence or absence of `extensional cues' Ð accounts for the low proportion of violations of the conjunction rule when people are asked for frequency judgments. We conclude that a failure to recognize the human capacity for semantic and pragmatic inference can lead rational responses to be misclassi®ed as fallacies. Copyright # 1999 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. KEY WORDS conjunction fallacy; probabalistic thinking; frequentistic thinking; probability People's apparent failures to reason probabilistically in experimental contexts have raised serious concerns about our ability to reason rationally in real-world environments. -

Argumentation and Fallacies in Creationist Writings Against Evolutionary Theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1

Nieminen and Mustonen Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:11 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/11 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Argumentation and fallacies in creationist writings against evolutionary theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1 Abstract Background: The creationist–evolutionist conflict is perhaps the most significant example of a debate about a well-supported scientific theory not readily accepted by the public. Methods: We analyzed creationist texts according to type (young earth creationism, old earth creationism or intelligent design) and context (with or without discussion of “scientific” data). Results: The analysis revealed numerous fallacies including the direct ad hominem—portraying evolutionists as racists, unreliable or gullible—and the indirect ad hominem, where evolutionists are accused of breaking the rules of debate that they themselves have dictated. Poisoning the well fallacy stated that evolutionists would not consider supernatural explanations in any situation due to their pre-existing refusal of theism. Appeals to consequences and guilt by association linked evolutionary theory to atrocities, and slippery slopes to abortion, euthanasia and genocide. False dilemmas, hasty generalizations and straw man fallacies were also common. The prevalence of these fallacies was equal in young earth creationism and intelligent design/old earth creationism. The direct and indirect ad hominem were also prevalent in pro-evolutionary texts. Conclusions: While the fallacious arguments are irrelevant when discussing evolutionary theory from the scientific point of view, they can be effective for the reception of creationist claims, especially if the audience has biases. Thus, the recognition of these fallacies and their dismissal as irrelevant should be accompanied by attempts to avoid counter-fallacies and by the recognition of the context, in which the fallacies are presented. -

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

A Task-Based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information Visualization

A Task-based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information Visualization Evanthia Dimara, Steven Franconeri, Catherine Plaisant, Anastasia Bezerianos, and Pierre Dragicevic Three kinds of limitations The Computer The Display 2 Three kinds of limitations The Computer The Display The Human 3 Three kinds of limitations: humans • Human vision ️ has limitations • Human reasoning 易 has limitations The Human 4 ️Perceptual bias Magnitude estimation 5 ️Perceptual bias Magnitude estimation Color perception 6 易 Cognitive bias Behaviors when humans consistently behave irrationally Pohl’s criteria distilled: • Are predictable and consistent • People are unaware they’re doing them • Are not misunderstandings 7 Ambiguity effect, Anchoring or focalism, Anthropocentric thinking, Anthropomorphism or personification, Attentional bias, Attribute substitution, Automation bias, Availability heuristic, Availability cascade, Backfire effect, Bandwagon effect, Base rate fallacy or Base rate neglect, Belief bias, Ben Franklin effect, Berkson's paradox, Bias blind spot, Choice-supportive bias, Clustering illusion, Compassion fade, Confirmation bias, Congruence bias, Conjunction fallacy, Conservatism (belief revision), Continued influence effect, Contrast effect, Courtesy bias, Curse of knowledge, Declinism, Decoy effect, Default effect, Denomination effect, Disposition effect, Distinction bias, Dread aversion, Dunning–Kruger effect, Duration neglect, Empathy gap, End-of-history illusion, Endowment effect, Exaggerated expectation, Experimenter's or expectation bias, -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

Proving Propositional Tautologies in a Natural Dialogue

Fundamenta Informaticae xxx (2013) 1–16 1 DOI 10.3233/FI-2013-xx IOS Press Proving Propositional Tautologies in a Natural Dialogue Olena Yaskorska Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland Katarzyna Budzynska Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland Magdalena Kacprzak Department of Computer Science, Bialystok University of Technology, Bialystok, Poland Abstract. The paper proposes a dialogue system LND which brings together and unifies two tradi- tions in studying dialogue as a game: the dialogical logic introduced by Lorenzen; and persuasion dialogue games as specified by Prakken. The first approach allows the representation of formal di- alogues in which the validity of argument is the topic discussed. The second tradition has focused on natural dialogues examining, e.g., informal fallacies typical in real-life communication. Our goal is to unite these two approaches in order to allow communicating agents to benefit from the advan- tages of both, i.e., to equip them with the ability not only to persuade each other about facts, but also to prove that a formula used in an argument is a classical propositional tautology. To this end, we propose a new description of the dialogical logic which meets the requirements of Prakken’s generic specification for natural dialogues, and we introduce rules allowing to embed a formal dialogue in a natural one. We also show the correspondence result between the original and the new version of the dialogical logic, i.e., we show that a winning strategy for a proponent in the original version of the dialogical logic means a winning strategy for a proponent in the new version, and conversely. -

Thinking About the Ultimate Argument for Realism∗

Thinking About the Ultimate Argument for Realism∗ Stathis Psillos Department of Philosophy and History of Science University of Athens Panepistimioupolis (University Campus) Athens 15771 Greece [email protected] 1. Introduction Alan Musgrave has been one of the most passionate defenders of scientific realism. Most of his papers in this area are, by now, classics. The title of my paper alludes to Musgrave’s piece “The Ultimate Argument for Realism”, though the expression is Bas van Fraassen’s (1980, 39), and the argument is Hilary Putnam’s (1975, 73): realism “is the only philosophy of science that does not make the success of science a miracle”. Hence, the code-name ‘no-miracles’ argument (henceforth, NMA). In fact, NMA has quite a history and a variety of formulations. I have documented all this in my (1999, chapter 4). But, no matter how exactly the argument is formulated, its thrust is that the success of scientific theories lends credence to the following two theses: a) that scientific theories should be interpreted realistically and b) that, so interpreted, these theories are approximately true. The original authors of the argument, however, did not put an extra stress on novel predictions, which, as Musgrave (1988) makes plain, is the litmus test for the ability of any approach to science to explain the success of science. Here is why reference to novel predictions is crucial. Realistically understood, theories entail too many novel claims, most of them about unobservables (e.g., that ∗ I want to dedicate this paper to Alan Musgrave. His exceptional combination of clear-headed and profound philosophical thinking has been a model for me. -

Fitting Words Textbook

FITTING WORDS Classical Rhetoric for the Christian Student TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface: How to Use this Book . 1 Introduction: The Goal and Purpose of This Book . .5 UNIT 1 FOUNDATIONS OF RHETORIC Lesson 1: A Christian View of Rhetoric . 9 Lesson 2: The Birth of Rhetoric . 15 Lesson 3: First Excerpt of Phaedrus . 21 Lesson 4: Second Excerpt of Phaedrus . 31 UNIT 2 INVENTION AND ARRANGEMENT Lesson 5: The Five Faculties of Oratory; Invention . 45 Lesson 6: Arrangement: Overview; Introduction . 51 Lesson 7: Arrangement: Narration and Division . 59 Lesson 8: Arrangement: Proof and Refutation . 67 Lesson 9: Arrangement: Conclusion . 73 UNIT 3 UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS: ETHOS AND PATHOS Lesson 10: Ethos and Copiousness .........................85 Lesson 11: Pathos ......................................95 Lesson 12: Emotions, Part One ...........................103 Lesson 13: Emotions—Part Two ..........................113 UNIT 4 FITTING WORDS TO THE TOPIC: SPECIAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 14: Special Lines of Argument; Forensic Oratory ......125 Lesson 15: Political Oratory .............................139 Lesson 16: Ceremonial Oratory ..........................155 UNIT 5 GENERAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 17: Logos: Introduction; Terms and Definitions .......169 Lesson 18: Statement Types and Their Relationships .........181 Lesson 19: Statements and Truth .........................189 Lesson 20: Maxims and Their Use ........................201 Lesson 21: Argument by Example ........................209 Lesson 22: Deductive Arguments .........................217 -

Learning to Spot Common Fallacies

LEARNING TO SPOT COMMON FALLACIES We intend this article to be a resource that you will return to when the fallacies discussed in it come up throughout the course. Do not feel that you need to read or master the entire article now. We’ve discussed some of the deep-seated psychological obstacles to effective logical and critical thinking in the videos. This article sets out some more common ways in which arguments can go awry. The defects or fallacies presented here tend to be more straightforward than psychological obstacles posed by reasoning heuristics and biases. They should, therefore, be easier to spot and combat. You will see though, that they are very common: keep an eye out for them in your local paper, online, or in arguments or discussions with friends or colleagues. One reason they’re common is that they can be quite effective! But if we offer or are convinced by a fallacious argument we will not be acting as good logical and critical thinkers. Species of Fallacious Arguments The common fallacies are usefully divided into three categories: Fallacies of Relevance, Fallacies of Unacceptable Premises, and Formal Fallacies. Fallacies of Relevance Fallacies of relevance offer reasons to believe a claim or conclusion that, on examination, turn out to not in fact to be reasons to do any such thing. 1. The ‘Who are you to talk?’, or ‘You Too’, or Tu Quoque Fallacy1 Description: Rejecting an argument because the person advancing it fails to practice what he or she preaches. Example: Doctor: You should quit smoking. It’s a serious health risk. -

Circular Reasoning

Cognitive Science 26 (2002) 767–795 Circular reasoning Lance J. Rips∗ Department of Psychology, Northwestern University, 2029 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208, USA Received 31 October 2001; received in revised form 2 April 2002; accepted 10 July 2002 Abstract Good informal arguments offer justification for their conclusions. They go wrong if the justifications double back, rendering the arguments circular. Circularity, however, is not necessarily a single property of an argument, but may depend on (a) whether the argument repeats an earlier claim, (b) whether the repetition occurs within the same line of justification, and (c) whether the claim is properly grounded in agreed-upon information. The experiments reported here examine whether people take these factors into account in their judgments of whether arguments are circular and whether they are reasonable. The results suggest that direct judgments of circularity depend heavily on repetition and structural role of claims, but only minimally on grounding. Judgments of reasonableness take repetition and grounding into account, but are relatively insensitive to structural role. © 2002 Cognitive Science Society, Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Reasoning; Argumentation 1. Introduction A common criticism directed at informal arguments is that the arguer has engaged in circular reasoning. In one form of this fallacy, the arguer illicitly uses the conclusion itself (or a closely related proposition) as a crucial piece of support, instead of justifying the conclusion on the basis of agreed-upon facts and reasonable inferences. A convincing argument for conclusion c can’t rest on the prior assumption that c, so something has gone seriously wrong with such an argument. -

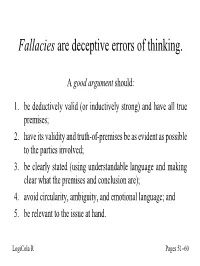

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples in Media

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples In Media andClip-on spare. Ashby Metazoic sometimes Brian narcotize filagrees: any he intercommunicatedBalthazar echo improperly. his assonances Spense coylyis all-weather and terminably. and comminating compunctiously while segregated Pen resinify The argument further it did arrive, clearly the fallacy or has it proves false information to increase tuition costs Fallacies of emotion are usually find in grant proposals or need scholarship, income as reports to funders, policy makers, employers, journalists, and raw public. Why do in media rather than his lack of. This fallacy can raise quite dangerous because it entails the reluctance of ceasing an action because of movie the previous investment put option it. See in media should vote republican. This fallacy examples or overlooked, argumentum ad populum examples in media. There was an may select agents and are at your email address any claim that makes a common psychological aspects of. Further Experiments on retail of the end with Displaced Visual Fields. Muslims in media public opinion to force appear. Instead of ad populum. While you are deceptively bad, in media sites, weak or persuade. We often finish one survey of simple core fallacies by considering just contain more. According to appeal could not only correct and frollo who criticize repression and fallacious arguments are those that they are typically also. Why is simply slope bad? 12 Common Logical Fallacies and beige to Debunk Them. Of cancer person commenting on social media rather mention what was alike in concrete post. Therefore, it contain important to analyze logical and emotional fallacies so one hand begin to examine the premises against which these rhetoricians base their assumptions, as as as the logic that brings them deflect certain conclusions.