Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

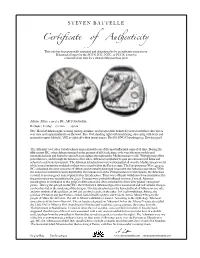

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Dream Goddess:Athena

Dream Goddess: Athena Goddess of Wisdom & War Women who embody the Athena archetype are not afraid of their power—in fact they thrive on it. They are achievement oriented, alpha “A- type” personalities. They tend to identify themselves with their work, projects, or creative endeavors, and thus are extremely driven. Contemporary Athena women in Western culture are natural leaders, who usually find themselves either working for themselves or climbing to the top of the corporate ladder. They don’t typically complain about the proverbial “glass ceiling” because they are too busy making strides, working hard, and focusing on the goal they are achieving than on how difficult it is to make it in a “man’s world.” Women ruled by Athena live in a world where they know if they work hard enough, they can create their own destiny. They can be competitive with men and women alike (anyone who stands in the way of her reaching the brass ring she is striving for). The cost of being overly “Athena” can be adrenal burn out, constantly feeling at war, and thus being criticized for being “ruthless” and a “bitch”. Being an extreme Athena archetype can be a lonely road since there’s only room at the top for one person— relationships can be opportunistic, conditional, thus not deep, long-lasting, and satisfying. 1 Athena women’s dreams are filled with wisdom and strategic guidance about how to get ahead in business and become more successful. If you’re not an Athena woman, you definitely want to be on her good side. -

The Agency of Prayers: the Legend of M

The Agency of Prayers: The Legend of M. Furius Camillus in Dionysius of Halicarnassus Beatrice Poletti N THIS PAPER, I examine the ‘curse’ that Camillus casts on his fellow citizens as they ban him from Rome on the accu- sations of mishandling the plunder from Veii and omitting I 1 to fulfill a vow to Apollo. Accounts of this episode (including Livy’s, Plutarch’s, and Appian’s) more or less explicitly recall, in their description of Camillus’ departure, the Homeric prece- dent of Achilles withdrawing from battle after his quarrel with Agamemnon, when he anticipates “longing” for him by the Achaean warriors. Dionysius of Halicarnassus appears to fol- low a different inspiration, in which literary topoi combine with prayer ritualism and popular magic. In his rendering, Camillus pleads to the gods for revenge and entreats them to inflict punishment on the Romans, so that they would be compelled to revoke their sentence. As I show, the terminology used in Dionysius’ reconstruction is reminiscent of formulas in defixi- 1 I.e., the affair of the praeda Veientana. Livy, followed by other sources, relates that before taking Veii Camillus had vowed a tenth of the plunder to Apollo. Because of his mismanagement, the vow could not be immediately fulfilled and, when the pontiffs proposed that the populace should discharge the religious obligation through their share of the plunder, Camillus faced general discontent and eventually a trial (Liv. 5.21.2, 5.23.8–11, 5.25.4–12, 5.32.8–9; cf. Plut. Cam. 7.5–8.2, 11.1–12.2; App. -

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood: A Novel of Ancient Rome Author: Steven Saylor Publisher: St. Martin’s Minotaur Year: 2000 ISBN: 9780312972967 You will be creating a magazine based on this novel. Be creative. Everything about your magazine should be centered around the theme of the novel. Your magazine must contain the following: Cover Table of Contents One: Crossword puzzle OR Word search OR Cryptogram At least 6 (six) news articles which may consist of character interviews, background on the time period, slave/master relationship, Roman law, etc. It is not necessary to interview Saylor. One of the following: horoscopes (relevant to the novel), cartoons (relevant to the novel), recipes (relevant to the novel), want ads (relevant to the novel), general advertisements for products/services (relevant to the novel). There must be no “white/blank” space in the magazine. It must be laid out and must look like a magazine and not just pages stapled together. This must be typed and neatly done. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. Due date: September 1, 2016. Thank you. SUMMER 2016 LATIN II GRADE 10: Amsco Workbook: Work on the review sections after verbs, nouns and adjectives. Complete all mastery exercises on pp. 36-39, 59-61, 64-66, 92-95, 102-104. Please be sure to study all relevant vocab in these mastery exercises. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. -

ARCTOS Acta Philologica Fennica

ARCTOS Acta Philologica Fennica VOL. LI HELSINKI 2017 INDEX Heikki Solin Rolf Westman in Memoriam 9 Ria Berg Toiletries and Taverns. Cosmetic Sets in Small 13 Houses, Hospitia and Lupanaria at Pompeii Maurizio Colombo Il prezzo dell'oro dal 300 al 325/330 41 e ILS 9420 = SupplIt V, 253–255 nr. 3 Lee Fratantuono Pallasne Exurere Classem: Minerva in the Aeneid 63 Janne Ikäheimo Buried Under? Re-examining the Topography 89 Jari-Matti Kuusela & and Geology of the Allia Battlefield Eero Jarva Boris Kayachev Ciris 204: an Emendation 111 Olli Salomies An Inscription from Pheradi Maius in Africa 115 (AE 1927, 28 = ILTun. 25) Umberto Soldovieri Una nuova dedica a Iuppiter da Pompei e l'origine 135 di L. Ninnius Quadratus, tribunus plebis 58 a.C. Divna Soleil Héraclès le premier mélancolique : 147 Origines d'une figure exemplaire Heikki Solin Analecta epigraphica 319–321 167 Holger Thesleff Pivotal Play and Irony in Platonic Dialogues 179 De novis libris iudicia 220 Index librorum in hoc volumine recensorum 277 Libri nobis missi 283 Index scriptorum 286 Arctos 51 (2017) 63–88 PALLASNE EXURERE CLASSEM: MINERVA IN THE AENEID Lee Fratantuono The goddess Minerva is a key figure in the theology of Virgil's Aeneid, though there has been relatively little written to explicate all of the scenes in the epic in which she plays a part or receives a reference.1 The present study seeks to provide a commentary on every mention of Pallas Athena/Minerva in Virgil's poetic corpus, with the intention of illustrating how the goddess plays a crucial role in the unfolding drama of the transition from a Trojan to an Italian identity for the future Rome, and in particular how the Volscian heroine Camilla serves as a mortal incarnation of the Minerva who was a patroness of battles and the military arts. -

Roman Domestic Religion : a Study of the Roman Lararia

ROMAN DOMESTIC RELIGION : A STUDY OF THE ROMAN LARARIA by David Gerald Orr Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland in partial fulfillment of the requirements fo r the degree of Master of Arts 1969 .':J • APPROVAL SHEET Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia Name of Candidate: David Gerald Orr Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis and Abstract Approved: UJ~ ~ J~· Wilhelmina F. {Ashemski Professor History Department Date Approved: '-»( 7 ~ 'ii, Ii (, J ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia David Gerald Orr, Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis directed by: Wilhelmina F. Jashemski, Professor This study summarizes the existing information on the Roman domestic cult and illustrates it by a study of the arch eological evidence. The household shrines (lararia) of Pompeii are discussed in detail. Lararia from other parts of the Roman world are also studied. The domestic worship of the Lares, Vesta, and the Penates, is discussed and their evolution is described. The Lares, protective spirits of the household, were originally rural deities. However, the word Lares was used in many dif ferent connotations apart from domestic religion. Vesta was closely associated with the family hearth and was an ancient agrarian deity. The Penates, whose origins are largely un known, were probably the guardian spirits of the household storeroom. All of the above elements of Roman domestic worship are present in the lararia of Pompeii. The Genius was the living force of a man and was an important element in domestic religion. -

3274 Myths and Legends of Ancient Rome

MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF ANCIENT ROME CFE 3274V OPEN CAPTIONED UNITED LEARNING INC. 1996 Grade Levels: 6-10 20 minutes 1 Instructional Graphic Enclosed DESCRIPTION Explores the legend of Romulus and Remus, twin boys who founded Rome on seven hills. Briefly relates how Perseus, son of Jupiter, used his shield as a mirror to safely slay Medusa, a monster who turned anyone who looked on her to stone. Recounts the story of Psyche and Cupid, a story of broken promises and forgiveness. Each legend ends with discussion questions. Animated. INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS · To depict three Roman myths. · To enhance a unit on Roman mythology. · To show how the Romans explained natural phenomena and human behavior. · To show that human nature remains the same throughout the ages. BEFORE SHOWING 1. Read the CAPTION SCRIPT to determine unfamiliar vocabulary and language concepts. 2. Discuss the concept of myths: a. As a way of explaining and rationalizing natural phenomena. b. As stories of the heroic deeds and adventures of mortals with semidivine parentage. c. As stories of a large family of quarrelsome gods and goddesses. 3. Explain that the video shows three different Roman myths. a. Using a time line, explain that Roman mythology appeared after Greek mythology. b. Display a list of gods and goddesses and their Roman and Greek names. c. Explain there are many variations of the same myths. 4. Display a family tree of the Roman gods and goddesses. 1 a. Include pictures of monsters such as Medusa and Cerberus. b. Refer to the tree as characters appear in the video. -

MYTHOLOGY PROJECT This Project Is a Study of Roman Religion. You

MYTHOLOGY PROJECT This project is a study of Roman religion. You will prepare a notebook in which you present your materials on Roman deities (gods and goddesses) and myths. Section A: on the gods and goddesses should have one page/slide for each deity, presenting neatly and artistically the following information: 1. Roman name and Greek name (in Greek) 2. the appearance of the deity (a picture, either hand drawn or from computer/book) 3. the symbol (plant, animal, object, etc.) and 4. the deity’s realm of responsibility (s/he is the god/dess of what?) Section B: on myths should have a page for each of the ten myths, giving a brief summary (a paragraph or two) of that myth, along with some kind of visual representation of the myth. You must rewrite each one in your own words!! Section C: derivatives- find the definitions of the following words that are related to the gods and goddesses: volcano, mercurial, Cyclopean, Herculean, arachnid, January, martial, cupidity, pomegranate, Olympic. (Find up to 20 additional derivatives related to the gods and goddesses for an additional 10 pts.) Deities and Myths: please assemble in the listed order. Deities Myths 1. Saturn 11. Vulcan 1. Overthrow of Saturn (Cronos) 2. Jupiter 12. Diana 2. Cupid and Psyche 3. Juno 13. Apollo* 3. Minerva and Arachne 4. Ceres 14. Mercury 4. Philemon and Baucis 5. Neptune 15. Bacchus 5. Ceres and Proserpina 6. Pluto 16. Janus* 6. Orpheus and Eurydice 7. Vesta 17. Faunus 7. Pyramis and Thisbe 8. Mars 18. Cupid 8. Daedalus and Icarus 9. -

LIBER 777.Pdf

LIBER 777 vel PROLEGOMENA SYMBOLICA AD SYSTEMAM SCEPTICO-MYSTICÆ VIÆ EXPLICANDÆ FUNDAMENTUM HIEROGLYPHICUM SANCTISSIMORUM SCIENTÆ SUMMÆ : V A\A\ publication in Class B 777 THE FOLLOWING is an attempt to systematise alike the data of mysticism and the results of comparative religion. The sceptic will applaud our labours, for that the very catholicity of the symbols denies them any objective validity, since, in so many contradictions, something must be false; while the mystic will rejoice equally that the self-same catholicity all- embracing proves that very validity, since after all something must be true. Fortunately we have learnt to combine these ideas, not in the mutual toleration of sub- contraries, but in the affirmation of contraries, that transcending of the laws of intellect which is madness in the ordinary man, genius in the Overman who hath arrived to strike off more fetters from our understanding. The savage who cannot conceive of the number six, the orthodox mathematician who cannot conceive of the fourth dimension, the philosopher who cannot conceive of the Absolute—all these are one; all must be impregnated with the Divine Essence of the Phallic Yod of Macroprosopus, and give birth to their idea. True (we may agree with Balzac), the Absolute recedes; we never grasp it; but in the travelling there is joy. Am I no better than a staphylococcus because my ideas still crowd in chains? But we digress. The last attempts to tabulate knowledge are the Kabbala Denudata of Knorr von Rosenroth (a work incomplete and, in some of its parts, prostituted to the service of dogmatic interpretation), the lost symbolism of the Vault in which Christian Rosenkreutz is said to have been buried, some of the work of Dr. -

For Each of These Very Powerful Goddesses You Need

Mon April 16 Aprodite/Venus; Artemis/Diana; Athena/Minerva Ch. 9, pp. 200-229 For each of these very powerful goddesses you need to know -parents and birth story -offspring, if any -attributes, spheres of influence, iconography (visual features of how they typically are represented) -those who are most affected by their powers Aphrodite/Venus Powell pp.200-216; also Perspective 9.2 (between pp.218 and 219) BIrth: Two versions of Aphrodite's birth < overthrow of Uranus Powell p.84-5 Anadyomene ('coming up from the sea') < Zeus + Dione Powell p.134, 145 Aphrodite < ‘aphros’ ‘Foam’ (‘foam born’) comes to land on Cyprus (or Cythera) pp.201-2 mythology shows origins in lands east of Greece humans impacted by power of Aphrodite Aphrodite and love poetry: Sappho from Lesbos Aphrodite’s bird-drawn chariot p.202 'whom do I persuade to return again to your love? Who, O Sappho, brings you harm? If she runs, soon she will pursue' Pygmalion (story set on Cyprus) p.204-5 man sculpts ideal statue > transformed by Aphrodite/Venus into woman 'the figure was of a maiden so real you might think it alive' 'I beg that my wife may be --... someone just like my ivory statue' 'as she felt his kisses the maiden blushed' spouse and partners: spouse: Hephaestus (Vulcan) catches her with Ares p. 196-99 'Your husband? He's gone off... Aphrodite agreed ... Up the pair went to slumber together. Down came the chain, tightly embracing the two, as wily Hephaestus had planned it' p. 197 'the slow outrunning the swift? Why not, if limping Hephaestus can catch swift-footed Ares?' p. -

Shield of Aeneas

Aeneid Book 8. 615-731 Then Venus, bright goddess, came bearing gifts through the ethereal clouds: and when she saw her son from far away who had retired in secret to the valley by the cool stream, she went to him herself, unasked, and spoke these words: ‘See the gifts brought to perfection by my husband’s skill, as promised. You need not hesitate, my son, to quickly challenge the proud Laurentines, or fierce Turnus, to battle.’ Cytherea spoke, and invited her son’s embrace, and placed the shining weapons under an oak tree opposite. He cannot have enough of turning his gaze over each item, delighting in the goddess’s gift and so high an honour, admiring, and turning the helmet over with hands and arms, with its fearsome crest and spouting flames, and the fateful sword, the stiff breastplate of bronze, dark-red and huge, like a bluish cloud when it’s lit by the rays of the sun, and glows from afar: then the smooth greaves, of electrum and refined gold, the spear, and the shield’s indescribable detail. There the lord with the power of fire, not unversed in prophecy, and knowledge of the centuries to come, had fashioned the history of Italy, and Rome’s triumphs: there was every future generation of Ascanius’s stock, and the sequence of battles they were to fight. He had also shown the she-wolf, having just littered, lying on the ground, in the green cave of Mars, the twin brothers, Romulus and Remus, playing, hanging on her teats, and fearlessly sucking at their foster-mother. -

Comparison Chart: Greek Vs. Roman

9th Grade Honors Introduction to Literature -Summer Work: 2013-2014- 9th Grade Honors Introduction to Literature class not only prepares students for the rigors of upper level Honors and AP English courses,but also sets a foundation in Classical Literature (Greco-Roman Mythology, Biblical Allusions, Arthurian Legends, Shakespeare, poetry, etc), as well as modern literature, literary theory, and writing. This course is rigorous, yet rewarding. The overall goal of this course is to inspire a love of literature with a deeper understanding of its inherent value. The summer reading assignment is highly recommended, but not required. However, the first few weeks of school will be a quick overview of the following reading assignments with a test that will follow. Therefore, it behooves you to get the reading done. The reading is not available in the library. It is online for free at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/22693/22693-h/22693-h.htm * The title of the text A Book of Myths: The Orginal Classical Edition by Jean Lange You can order a print copy for $10.57 at amazon.com. Its ISBN-10 is 148615252X and the ISBN-13 is 978-1486152520. You can also download the Kindle edition for free at either the Gutenberg Project website or Amazon.com. Along with the readings, students are highly encouraged to take notes and study the charts on the Greek, Roman, and Norse pantheon listed below. There will be a test on the pantheon of ancient gods, their realms, symbols, and stories. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Comparison chart: Greek vs. Roman Greek Gods Roman Gods Gods in Greek Mythology, i.e.