The Agency of Prayers: the Legend of M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ceificate of Auenticity

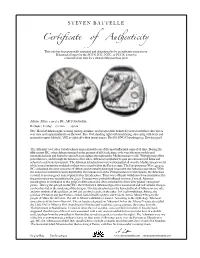

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna

Brief Chronicles IV (2012-13) 89 Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna: A Study in Jacobean Literary Form Roger Stritmatter his article investigates the presence of a concealed and previously undetected numerical symbolism in a Stuart-era emblem book, Henry TPeacham’s Minerva Britanna (1611). Although alien to modern conceptions of art, emblem books constitute one of the most widely published and popular genres in early modern book production. Drawing from an eclectic tradition of literary, religious, and iconological traditions, the emblem book combined words and images into complex patterns of signification, often of a markedly didactic character. Popular in all the European vernaculars, it appealed to a wide range of Renaissance readers, from the nearly illiterate (by virtue of its illustrated nature) to the most erudite (by virtue of its reputation for dazzling displays of intellectual and aesthetic virtuosity). By convention the emblem was divided into three parts: superscriptio, pictura, and subscriptio: the superscriptio was the short legend or motto that typically appeared at the top of the page; below it appeared the pictura – the emblem per se – followed by the subscriptio, a longer responsive analysis, usually written in verse, which completed the design. While emblem book scholars still debate the exact relationship between the three parts – and no doubt individual emblem writers themselves sometimes conceived of it in different ways, Deitrich Walter Jöns’ definition constitutes a useful and standard point -

Dream Goddess:Athena

Dream Goddess: Athena Goddess of Wisdom & War Women who embody the Athena archetype are not afraid of their power—in fact they thrive on it. They are achievement oriented, alpha “A- type” personalities. They tend to identify themselves with their work, projects, or creative endeavors, and thus are extremely driven. Contemporary Athena women in Western culture are natural leaders, who usually find themselves either working for themselves or climbing to the top of the corporate ladder. They don’t typically complain about the proverbial “glass ceiling” because they are too busy making strides, working hard, and focusing on the goal they are achieving than on how difficult it is to make it in a “man’s world.” Women ruled by Athena live in a world where they know if they work hard enough, they can create their own destiny. They can be competitive with men and women alike (anyone who stands in the way of her reaching the brass ring she is striving for). The cost of being overly “Athena” can be adrenal burn out, constantly feeling at war, and thus being criticized for being “ruthless” and a “bitch”. Being an extreme Athena archetype can be a lonely road since there’s only room at the top for one person— relationships can be opportunistic, conditional, thus not deep, long-lasting, and satisfying. 1 Athena women’s dreams are filled with wisdom and strategic guidance about how to get ahead in business and become more successful. If you’re not an Athena woman, you definitely want to be on her good side. -

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood: A Novel of Ancient Rome Author: Steven Saylor Publisher: St. Martin’s Minotaur Year: 2000 ISBN: 9780312972967 You will be creating a magazine based on this novel. Be creative. Everything about your magazine should be centered around the theme of the novel. Your magazine must contain the following: Cover Table of Contents One: Crossword puzzle OR Word search OR Cryptogram At least 6 (six) news articles which may consist of character interviews, background on the time period, slave/master relationship, Roman law, etc. It is not necessary to interview Saylor. One of the following: horoscopes (relevant to the novel), cartoons (relevant to the novel), recipes (relevant to the novel), want ads (relevant to the novel), general advertisements for products/services (relevant to the novel). There must be no “white/blank” space in the magazine. It must be laid out and must look like a magazine and not just pages stapled together. This must be typed and neatly done. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. Due date: September 1, 2016. Thank you. SUMMER 2016 LATIN II GRADE 10: Amsco Workbook: Work on the review sections after verbs, nouns and adjectives. Complete all mastery exercises on pp. 36-39, 59-61, 64-66, 92-95, 102-104. Please be sure to study all relevant vocab in these mastery exercises. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. -

ARCTOS Acta Philologica Fennica

ARCTOS Acta Philologica Fennica VOL. LI HELSINKI 2017 INDEX Heikki Solin Rolf Westman in Memoriam 9 Ria Berg Toiletries and Taverns. Cosmetic Sets in Small 13 Houses, Hospitia and Lupanaria at Pompeii Maurizio Colombo Il prezzo dell'oro dal 300 al 325/330 41 e ILS 9420 = SupplIt V, 253–255 nr. 3 Lee Fratantuono Pallasne Exurere Classem: Minerva in the Aeneid 63 Janne Ikäheimo Buried Under? Re-examining the Topography 89 Jari-Matti Kuusela & and Geology of the Allia Battlefield Eero Jarva Boris Kayachev Ciris 204: an Emendation 111 Olli Salomies An Inscription from Pheradi Maius in Africa 115 (AE 1927, 28 = ILTun. 25) Umberto Soldovieri Una nuova dedica a Iuppiter da Pompei e l'origine 135 di L. Ninnius Quadratus, tribunus plebis 58 a.C. Divna Soleil Héraclès le premier mélancolique : 147 Origines d'une figure exemplaire Heikki Solin Analecta epigraphica 319–321 167 Holger Thesleff Pivotal Play and Irony in Platonic Dialogues 179 De novis libris iudicia 220 Index librorum in hoc volumine recensorum 277 Libri nobis missi 283 Index scriptorum 286 Arctos 51 (2017) 63–88 PALLASNE EXURERE CLASSEM: MINERVA IN THE AENEID Lee Fratantuono The goddess Minerva is a key figure in the theology of Virgil's Aeneid, though there has been relatively little written to explicate all of the scenes in the epic in which she plays a part or receives a reference.1 The present study seeks to provide a commentary on every mention of Pallas Athena/Minerva in Virgil's poetic corpus, with the intention of illustrating how the goddess plays a crucial role in the unfolding drama of the transition from a Trojan to an Italian identity for the future Rome, and in particular how the Volscian heroine Camilla serves as a mortal incarnation of the Minerva who was a patroness of battles and the military arts. -

The Emergence of Archival Records at Rome in the Fourth Century BCE

Foundations of History: The Emergence of Archival Records at Rome in the Fourth Century BCE by Zachary B. Hallock A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Potter, Chair Associate Professor Benjamin Fortson Assistant Professor Brendan Haug Professor Nicola Terrenato Zachary B. Hallock [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0337-0181 © 2018 by Zachary B. Hallock To my parents for their endless love and support ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Rackham Graduate School and the Departments of Classics and History for providing me with the resources and support that made my time as a graduate student comfortable and enjoyable. I would also like to express my gratitude to the professors of these departments who made themselves and their expertise abundantly available. Their mentoring and guidance proved invaluable and have shaped my approach to solving the problems of the past. I am an immensely better thinker and teacher through their efforts. I would also like to express my appreciation to my committee, whose diligence and attention made this project possible. I will be forever in their debt for the time they committed to reading and discussing my work. I would particularly like to thank my chair, David Potter, who has acted as a mentor and guide throughout my time at Michigan and has had the greatest role in making me the scholar that I am today. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Andrea, who has been and will always be my greatest interlocutor. -

A Handbook of Greek and Roman Coins

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library CJ 237.H64 A handbook of Greek and Roman coins. 3 1924 021 438 399 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021438399 f^antilioofcs of glrcfjaeologj) anU Antiquities A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS G. F. HILL, M.A. OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COINS AND MEDALS IN' THE bRITISH MUSEUM WITH FIFTEEN COLLOTYPE PLATES Hon&on MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY l8 99 \_All rights reserved'] ©jcforb HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE The attempt has often been made to condense into a small volume all that is necessary for a beginner in numismatics or a young collector of coins. But success has been less frequent, because the knowledge of coins is essentially a knowledge of details, and small treatises are apt to be un- readable when they contain too many references to particular coins, and unprofltably vague when such references are avoided. I cannot hope that I have passed safely between these two dangers ; indeed, my desire has been to avoid the second at all risk of encountering the former. At the same time it may be said that this book is not meant for the collector who desires only to identify the coins which he happens to possess, while caring little for the wider problems of history, art, mythology, and religion, to which coins sometimes furnish the only key. -

Roman Domestic Religion : a Study of the Roman Lararia

ROMAN DOMESTIC RELIGION : A STUDY OF THE ROMAN LARARIA by David Gerald Orr Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland in partial fulfillment of the requirements fo r the degree of Master of Arts 1969 .':J • APPROVAL SHEET Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia Name of Candidate: David Gerald Orr Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis and Abstract Approved: UJ~ ~ J~· Wilhelmina F. {Ashemski Professor History Department Date Approved: '-»( 7 ~ 'ii, Ii (, J ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia David Gerald Orr, Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis directed by: Wilhelmina F. Jashemski, Professor This study summarizes the existing information on the Roman domestic cult and illustrates it by a study of the arch eological evidence. The household shrines (lararia) of Pompeii are discussed in detail. Lararia from other parts of the Roman world are also studied. The domestic worship of the Lares, Vesta, and the Penates, is discussed and their evolution is described. The Lares, protective spirits of the household, were originally rural deities. However, the word Lares was used in many dif ferent connotations apart from domestic religion. Vesta was closely associated with the family hearth and was an ancient agrarian deity. The Penates, whose origins are largely un known, were probably the guardian spirits of the household storeroom. All of the above elements of Roman domestic worship are present in the lararia of Pompeii. The Genius was the living force of a man and was an important element in domestic religion. -

3274 Myths and Legends of Ancient Rome

MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF ANCIENT ROME CFE 3274V OPEN CAPTIONED UNITED LEARNING INC. 1996 Grade Levels: 6-10 20 minutes 1 Instructional Graphic Enclosed DESCRIPTION Explores the legend of Romulus and Remus, twin boys who founded Rome on seven hills. Briefly relates how Perseus, son of Jupiter, used his shield as a mirror to safely slay Medusa, a monster who turned anyone who looked on her to stone. Recounts the story of Psyche and Cupid, a story of broken promises and forgiveness. Each legend ends with discussion questions. Animated. INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS · To depict three Roman myths. · To enhance a unit on Roman mythology. · To show how the Romans explained natural phenomena and human behavior. · To show that human nature remains the same throughout the ages. BEFORE SHOWING 1. Read the CAPTION SCRIPT to determine unfamiliar vocabulary and language concepts. 2. Discuss the concept of myths: a. As a way of explaining and rationalizing natural phenomena. b. As stories of the heroic deeds and adventures of mortals with semidivine parentage. c. As stories of a large family of quarrelsome gods and goddesses. 3. Explain that the video shows three different Roman myths. a. Using a time line, explain that Roman mythology appeared after Greek mythology. b. Display a list of gods and goddesses and their Roman and Greek names. c. Explain there are many variations of the same myths. 4. Display a family tree of the Roman gods and goddesses. 1 a. Include pictures of monsters such as Medusa and Cerberus. b. Refer to the tree as characters appear in the video. -

Chapter Two: the Annalistic Form

FORM, INTENT, AND THE FRAGMENTARY ROMAN HISTORIANS 240 to 63 B.C.E. By GERTRUDE HARRINGTON BECKER A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 2008 Gertrude Harrington Becker 2 To Andy 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many have helped me on my journey through the long Ph.D. process. Writing is often a lonely and isolating task but I was lucky never to feel alone. For that I owe thanks to a multitude of friends who cheered me, colleagues who read my work, my department (and Dean) at Virginia Tech which allowed me time off to write, and parents who supported my every step. I also thank the many women who showed me it was possible to complete schooling and a Ph.D. later in life, in particular my mother, Trudy Harrington, and my mother-in-law, Judith Becker. Above all, I thank my family: my children, Matt, Tim, and Trudy for their regular brilliance; and my husband, Andy, who is my center, cornerstone, and rock, this year, the past 21 years, and more to come. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................7 1 EARLY ROMAN HISTORIOGRAPHY: PAST AND PRESENT .........................................9 2 FOUNDERS AND FOLLOWERS: EARLY ROMAN ANNALISTS IN GREEK ..............37 Annales -

MYTHOLOGY PROJECT This Project Is a Study of Roman Religion. You

MYTHOLOGY PROJECT This project is a study of Roman religion. You will prepare a notebook in which you present your materials on Roman deities (gods and goddesses) and myths. Section A: on the gods and goddesses should have one page/slide for each deity, presenting neatly and artistically the following information: 1. Roman name and Greek name (in Greek) 2. the appearance of the deity (a picture, either hand drawn or from computer/book) 3. the symbol (plant, animal, object, etc.) and 4. the deity’s realm of responsibility (s/he is the god/dess of what?) Section B: on myths should have a page for each of the ten myths, giving a brief summary (a paragraph or two) of that myth, along with some kind of visual representation of the myth. You must rewrite each one in your own words!! Section C: derivatives- find the definitions of the following words that are related to the gods and goddesses: volcano, mercurial, Cyclopean, Herculean, arachnid, January, martial, cupidity, pomegranate, Olympic. (Find up to 20 additional derivatives related to the gods and goddesses for an additional 10 pts.) Deities and Myths: please assemble in the listed order. Deities Myths 1. Saturn 11. Vulcan 1. Overthrow of Saturn (Cronos) 2. Jupiter 12. Diana 2. Cupid and Psyche 3. Juno 13. Apollo* 3. Minerva and Arachne 4. Ceres 14. Mercury 4. Philemon and Baucis 5. Neptune 15. Bacchus 5. Ceres and Proserpina 6. Pluto 16. Janus* 6. Orpheus and Eurydice 7. Vesta 17. Faunus 7. Pyramis and Thisbe 8. Mars 18. Cupid 8. Daedalus and Icarus 9. -

Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography Jennifer Gerrish University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Gerrish, Jennifer, "Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 511. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/511 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/511 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography Abstract This dissertation explores echoes of the triumviral period in Sallust's Histories and demonstrates how, through analogical historiography, Sallust presents himself as a new type of historian whose "exempla" are flawed and morally ambiguous, and who rejects the notion of a triumphant, ascendant Rome perpetuated by the triumvirs. Just as Sallust's unusual prose style is calculated to shake his reader out of complacency and force critical engagement with the reading process, his analogical historiography requires the reader to work through multiple layers of interpretation to reach the core arguments. In the De Legibus, Cicero lamented the lack of great Roman historians, and frequently implied that he might take up the task himself. He had a clear sense of what history ought to be : encomiastic and exemplary, reflecting a conception of Roman history as a triumphant story populated by glorious protagonists. In Sallust's view, however, the novel political circumstances of the triumviral period called for a new type of historiography. To create a portrait of moral clarity is, Sallust suggests, ineffective, because Romans have been too corrupted by ambitio and avaritia to follow the good examples of the past.