ARCTOS Acta Philologica Fennica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Copa: an Introduction and Commentary

THE COPA: AN INTRODUCTION AND COMMENTARY by FRANCES J. GRUENEWALD B.A., University of British Columbia, 1972 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1975 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date AlfJL 3L<\t /<?7S. ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is two-fold: firstly, to make a general study of the Copa with a view to determining, as far as is possible, its authorship and date, and,secondly, to attempt a detailed exegesis of its contents. The first Chapter contains an introduction to the MSS tradi• tion of the Appendix Vergiliana, and a brief discussion of the statements of Donatus and Servius concerning Vergilian authorship of the poems. In Chapter 2 the question of the authorship of the Copa is considered. The views of various scholars, who use as tests of authenticity studies of content and style, vocabulary, metre and parallel passages, are discussed. -

Trojan Women: Introduction

Trojan Women: Introduction 1. Gods in the Trojan Women Two gods take the stage in the prologue to Trojan Women. Are these gods real or abstract? In the prologue, with its monologue by Poseidon followed by a dialogue between the master of the sea and Athena, we see them as real, as actors (perhaps statelier than us, and accoutered with their traditional props, a trident for the sea god, a helmet for Zeus’ daughter). They are otherwise quite ordinary people with their loves and hates and with their infernal flexibility whether moral or emotional. They keep their emotional side removed from humans, distance which will soon become physical. Poseidon cannot stay in Troy, because the citizens don’t worship him any longer. He may feel sadness or regret, but not mourning for the people who once worshiped but now are dead or soon to be dispersed. He is not present for the destruction of the towers that signal his final absence and the diaspora of his Phrygians. He takes pride in the building of the walls, perfected by the use of mason’s rules. After the divine departures, the play proceeds to the inanition of his and Apollo’s labor, with one more use for the towers before they are wiped from the face of the earth. Nothing will be left. It is true, as Hecuba claims, her last vestige of pride, the name of Troy remains, but the place wandered about throughout antiquity and into the modern age. At the end of his monologue Poseidon can still say farewell to the towers. -

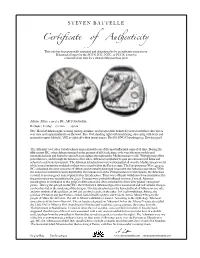

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

THE MYTH of ORPHEUS and EURYDICE in WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., Universi

THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., University of Toronto, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY in the Department of- Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, i960 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada. ©he Pttttrerstt^ of ^riitsl} (Eolimtbta FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A. University of Toronto, 1953 M.A. University of Toronto, 1957 S.T.B. University of Toronto, 1957 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1960 AT 3:00 P.M. IN ROOM 256, BUCHANAN BUILDING COMMITTEE IN CHARGE DEAN G. M. SHRUM, Chairman M. F. MCGREGOR G. B. RIDDEHOUGH W. L. GRANT P. C. F. GUTHRIE C. W. J. ELIOT B. SAVERY G. W. MARQUIS A. E. BIRNEY External Examiner: T. G. ROSENMEYER University of Washington THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN Myth sometimes evolves art-forms in which to express itself: LITERATURE Politian's Orfeo, a secular subject, which used music to tell its story, is seen to be the forerunner of the opera (Chapter IV); later, the ABSTRACT myth of Orpheus and Eurydice evolved the opera, in the works of the Florentine Camerata and Monteverdi, and served as the pattern This dissertion traces the course of the myth of Orpheus and for its reform, in Gluck (Chapter V). -

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars. -

Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna

Brief Chronicles IV (2012-13) 89 Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna: A Study in Jacobean Literary Form Roger Stritmatter his article investigates the presence of a concealed and previously undetected numerical symbolism in a Stuart-era emblem book, Henry TPeacham’s Minerva Britanna (1611). Although alien to modern conceptions of art, emblem books constitute one of the most widely published and popular genres in early modern book production. Drawing from an eclectic tradition of literary, religious, and iconological traditions, the emblem book combined words and images into complex patterns of signification, often of a markedly didactic character. Popular in all the European vernaculars, it appealed to a wide range of Renaissance readers, from the nearly illiterate (by virtue of its illustrated nature) to the most erudite (by virtue of its reputation for dazzling displays of intellectual and aesthetic virtuosity). By convention the emblem was divided into three parts: superscriptio, pictura, and subscriptio: the superscriptio was the short legend or motto that typically appeared at the top of the page; below it appeared the pictura – the emblem per se – followed by the subscriptio, a longer responsive analysis, usually written in verse, which completed the design. While emblem book scholars still debate the exact relationship between the three parts – and no doubt individual emblem writers themselves sometimes conceived of it in different ways, Deitrich Walter Jöns’ definition constitutes a useful and standard point -

Dream Goddess:Athena

Dream Goddess: Athena Goddess of Wisdom & War Women who embody the Athena archetype are not afraid of their power—in fact they thrive on it. They are achievement oriented, alpha “A- type” personalities. They tend to identify themselves with their work, projects, or creative endeavors, and thus are extremely driven. Contemporary Athena women in Western culture are natural leaders, who usually find themselves either working for themselves or climbing to the top of the corporate ladder. They don’t typically complain about the proverbial “glass ceiling” because they are too busy making strides, working hard, and focusing on the goal they are achieving than on how difficult it is to make it in a “man’s world.” Women ruled by Athena live in a world where they know if they work hard enough, they can create their own destiny. They can be competitive with men and women alike (anyone who stands in the way of her reaching the brass ring she is striving for). The cost of being overly “Athena” can be adrenal burn out, constantly feeling at war, and thus being criticized for being “ruthless” and a “bitch”. Being an extreme Athena archetype can be a lonely road since there’s only room at the top for one person— relationships can be opportunistic, conditional, thus not deep, long-lasting, and satisfying. 1 Athena women’s dreams are filled with wisdom and strategic guidance about how to get ahead in business and become more successful. If you’re not an Athena woman, you definitely want to be on her good side. -

TSJCL 2006 Upper Rd 1 Pg 1 2006 Texas State JCL Certamen Upper

2006 Texas State JCL Certamen Upper Round 1 TU # 1: As she was crossing a body of water, what did Helle fall off of? A GOLDEN RAM B1: Whose threats were Phrixus and Helle escaping? INO, THEIR STEP-MOTHER B2: What did Phrixus do when he safely landed in Colchis? SACRIFICED THE RAM TU # 2: Where did Antony win a battle and, three weeks later, win another, bringing to an end a civil war in 42 BC? PHILIPPI B1: Soon after this battle, Antony and Octavian removed themselves from their partner in the triumvirate. Who was this partner? LEPIDUS B2: What two relatives of Antony caused trouble the following year by trying to stir up hostility against Octavian? HIS WIFE FULVIA AND HIS BROTHER LUCIUS TU # 3: Which Roman author is described by the following: Caesar seems to have been a guest in his house at one point; he was about 15 years younger than Caesar and seems to have died at age thirty; we have 113 of his poems, many of which mention his affair with a married woman. CATULLUS B1: To whom did Catullus dedicate his book of poems, according to poem 1 in the collection? CORNELIUS NEPOS B2: Translate this line from Catullus: “passer mortuus est meae puellae.” MY GIRL’S SPARROW / DOVE IS DEAD TU # 4: Give all the participles of the verb ferÇ, ferre. FERNS, L}TUS, L}TâRUS, FERENDUS B1: Give all the participles for the verb arbitror. ARBITR}NS, ARBITR}TUS, ARBITR}TâRUS, ARBITRANDUS B2: Give all the infinitives for arbitror. ARBITR}R¦, ARBITR}TUS ESSE, ARBITR}TâRUS ESSE TU # 5: What king of Elis remained young forever by choosing perpetual sleep as -

Hostage to Feminism? the Success of Christa Wolf's Kassandra in Its 1984

This is a repository copy of Hostage to feminism? The success of Christa Wolf’s Kassandra in its 1984 English translation. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/127025/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Summers, C (2018) Hostage to feminism? The success of Christa Wolf’s Kassandra in its 1984 English translation. Gender and History, 30 (1). pp. 226-239. ISSN 0953-5233 https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.12345 © 2018 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Summers, C (2018) Hostage to feminism? The success of Christa Wolf’s Kassandra in its 1984 English translation. Gender and History, 30 (1). pp. 226-239, which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.12345. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

The Agency of Prayers: the Legend of M

The Agency of Prayers: The Legend of M. Furius Camillus in Dionysius of Halicarnassus Beatrice Poletti N THIS PAPER, I examine the ‘curse’ that Camillus casts on his fellow citizens as they ban him from Rome on the accu- sations of mishandling the plunder from Veii and omitting I 1 to fulfill a vow to Apollo. Accounts of this episode (including Livy’s, Plutarch’s, and Appian’s) more or less explicitly recall, in their description of Camillus’ departure, the Homeric prece- dent of Achilles withdrawing from battle after his quarrel with Agamemnon, when he anticipates “longing” for him by the Achaean warriors. Dionysius of Halicarnassus appears to fol- low a different inspiration, in which literary topoi combine with prayer ritualism and popular magic. In his rendering, Camillus pleads to the gods for revenge and entreats them to inflict punishment on the Romans, so that they would be compelled to revoke their sentence. As I show, the terminology used in Dionysius’ reconstruction is reminiscent of formulas in defixi- 1 I.e., the affair of the praeda Veientana. Livy, followed by other sources, relates that before taking Veii Camillus had vowed a tenth of the plunder to Apollo. Because of his mismanagement, the vow could not be immediately fulfilled and, when the pontiffs proposed that the populace should discharge the religious obligation through their share of the plunder, Camillus faced general discontent and eventually a trial (Liv. 5.21.2, 5.23.8–11, 5.25.4–12, 5.32.8–9; cf. Plut. Cam. 7.5–8.2, 11.1–12.2; App. -

Study Questions Helen of Troycomp

Study Questions Helen of Troy 1. What does Paris say about Agamemnon? That he treated Helen as a slave and he would have attacked Troy anyway. 2. What is Priam’s reaction to Paris’ action? What is Paris’ response? Priam is initially very upset with his son. Paris tries to defend himself and convince his father that he should allow Helen to stay because of her poor treatment. 3. What does Cassandra say when she first sees Helen? What warning does she give? Cassandra identifies Helen as a Spartan and says she does not belong there. Cassandra warns that Helen will bring about the end of Troy. 4. What does Helen say she wants to do? Why do you think she does this? She says she wants to return to her husband. She is probably doing this in an attempt to save lives. 5. What does Menelaus ask of King Priam? Who goes with him? Menelaus asks for his wife back. Odysseus goes with him. 6. How does Odysseus’ approach to Priam differ from Menelaus’? Who seems to be more successful? Odysseus reasons with Priam and tries to appeal to his sense of propriety; Menelaus simply threatened. Odysseus seems to be more successful; Priam actually considers his offer. 7. Why does Priam decide against returning Helen? What offer does he make to her? He finds out that Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter for safe passage to Troy; Agamemnon does not believe that is an action suited to a king. Priam offers Helen the opportunity to become Helen of Troy. 8. What do Agamemnon and Achilles do as the rest of the Greek army lands on the Trojan coast? They disguise themselves and sneak into the city. -

ABSTRACT a Director's Approach to Euripides' Hecuba Christopher F. Peck, M.F.A. Mentor: Deanna Toten Beard, Ph.D. This Thesi

ABSTRACT A Director’s Approach to Euripides’ Hecuba Christopher F. Peck, M.F.A. Mentor: DeAnna Toten Beard, Ph.D. This thesis explores a production of Euripides’ Hecuba as it was directed by Christopher Peck. Chapter One articulates a unique Euripidean dramatic structure to demonstrate the contemporary viability of Euripides’ play. Chapter Two utilizes this dramatic structure as the basis for an aggressive analysis of themes inherent in the production. Chapter Three is devoted to the conceptualization of this particular production and the relationship between the director and the designers in pursuit of this concept. Chapter Four catalogs the rehearsal process and how the director and actors worked together to realize the dramatic needs of the production. Finally Chapter Five is a postmortem of the production emphasizing the strengths and weaknesses of the final product of Baylor University’s Hecuba. A Director's Approach to Euripides' Hecuba by Christopher F. Peck, B.F.A A Thesis Approved by the Department of Theatre Arts Stan C. Denman, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee DeAnna Toten Beard, Ph.D., Chairperson David J. Jortner, Ph.D. Marion D. Castleberry, Ph.D. Steven C. Pounders, M.F.A. Christopher J. Hansen, M.F.A. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2013 J. Larry Lyon, Ph.D., Dean Page bearing signatures is kept on file in the Graduate School. Copyright © 2013 by Christopher F. Peck