The Comparison of Art in the Carmina Priapea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

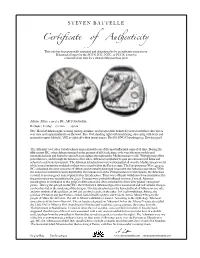

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna

Brief Chronicles IV (2012-13) 89 Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna: A Study in Jacobean Literary Form Roger Stritmatter his article investigates the presence of a concealed and previously undetected numerical symbolism in a Stuart-era emblem book, Henry TPeacham’s Minerva Britanna (1611). Although alien to modern conceptions of art, emblem books constitute one of the most widely published and popular genres in early modern book production. Drawing from an eclectic tradition of literary, religious, and iconological traditions, the emblem book combined words and images into complex patterns of signification, often of a markedly didactic character. Popular in all the European vernaculars, it appealed to a wide range of Renaissance readers, from the nearly illiterate (by virtue of its illustrated nature) to the most erudite (by virtue of its reputation for dazzling displays of intellectual and aesthetic virtuosity). By convention the emblem was divided into three parts: superscriptio, pictura, and subscriptio: the superscriptio was the short legend or motto that typically appeared at the top of the page; below it appeared the pictura – the emblem per se – followed by the subscriptio, a longer responsive analysis, usually written in verse, which completed the design. While emblem book scholars still debate the exact relationship between the three parts – and no doubt individual emblem writers themselves sometimes conceived of it in different ways, Deitrich Walter Jöns’ definition constitutes a useful and standard point -

Dream Goddess:Athena

Dream Goddess: Athena Goddess of Wisdom & War Women who embody the Athena archetype are not afraid of their power—in fact they thrive on it. They are achievement oriented, alpha “A- type” personalities. They tend to identify themselves with their work, projects, or creative endeavors, and thus are extremely driven. Contemporary Athena women in Western culture are natural leaders, who usually find themselves either working for themselves or climbing to the top of the corporate ladder. They don’t typically complain about the proverbial “glass ceiling” because they are too busy making strides, working hard, and focusing on the goal they are achieving than on how difficult it is to make it in a “man’s world.” Women ruled by Athena live in a world where they know if they work hard enough, they can create their own destiny. They can be competitive with men and women alike (anyone who stands in the way of her reaching the brass ring she is striving for). The cost of being overly “Athena” can be adrenal burn out, constantly feeling at war, and thus being criticized for being “ruthless” and a “bitch”. Being an extreme Athena archetype can be a lonely road since there’s only room at the top for one person— relationships can be opportunistic, conditional, thus not deep, long-lasting, and satisfying. 1 Athena women’s dreams are filled with wisdom and strategic guidance about how to get ahead in business and become more successful. If you’re not an Athena woman, you definitely want to be on her good side. -

Temples and Priests of Sol in the City of Rome

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242330197 Temples and Priests of Sol in the City of Rome Article in Mouseion Journal of the Classical Association of Canada · January 2010 DOI: 10.1353/mou.2010.0073 CITATIONS READS 0 550 1 author: S. E. Hijmans University of Alberta 23 PUBLICATIONS 9 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: S. E. Hijmans Retrieved on: 03 November 2016 Temples and Priests of Sol in the city of Rome Summary It was long thought that Sol Invictus was a Syrian sun-god, and that Aurelian imported his cult into Rome after he had vanquished Zenobia and captured Palmyra. This sun-god, it was postulated, differed fundamentally from the old Roman sun-god Sol Indiges, whose cult had long since disappeared from Rome. Scholars thus tended to postulate a hiatus in the first centuries of imperial rule during which there was little or no cult of the sun in Rome. Recent studies, however, have shown that Aurelian’s Sol Invictus was neither new nor foreign, and that the cult of the sun was maintained in Rome without interruption from the city’s earliest history until the demise of Roman religion(s). This continuity of the Roman cult of Sol sheds a new light on the evidence for priests and temples of Sol in Rome. In this article I offer a review of that evidence and what we can infer from it the Roman cult of the sun. A significant portion of the article is devoted to a temple of Sol in Trastevere, hitherto misidentified. -

The Agency of Prayers: the Legend of M

The Agency of Prayers: The Legend of M. Furius Camillus in Dionysius of Halicarnassus Beatrice Poletti N THIS PAPER, I examine the ‘curse’ that Camillus casts on his fellow citizens as they ban him from Rome on the accu- sations of mishandling the plunder from Veii and omitting I 1 to fulfill a vow to Apollo. Accounts of this episode (including Livy’s, Plutarch’s, and Appian’s) more or less explicitly recall, in their description of Camillus’ departure, the Homeric prece- dent of Achilles withdrawing from battle after his quarrel with Agamemnon, when he anticipates “longing” for him by the Achaean warriors. Dionysius of Halicarnassus appears to fol- low a different inspiration, in which literary topoi combine with prayer ritualism and popular magic. In his rendering, Camillus pleads to the gods for revenge and entreats them to inflict punishment on the Romans, so that they would be compelled to revoke their sentence. As I show, the terminology used in Dionysius’ reconstruction is reminiscent of formulas in defixi- 1 I.e., the affair of the praeda Veientana. Livy, followed by other sources, relates that before taking Veii Camillus had vowed a tenth of the plunder to Apollo. Because of his mismanagement, the vow could not be immediately fulfilled and, when the pontiffs proposed that the populace should discharge the religious obligation through their share of the plunder, Camillus faced general discontent and eventually a trial (Liv. 5.21.2, 5.23.8–11, 5.25.4–12, 5.32.8–9; cf. Plut. Cam. 7.5–8.2, 11.1–12.2; App. -

Caecilia, Calpurnia, and Their Dreams of Political Importance. Patterns of Constructing Gender Relations and Female Scope for Action in Ancient Roman Sources

Athens Journal of History - Volume 4, Issue 2 – Pages 93-116 Caecilia, Calpurnia, and Their Dreams of Political Importance. Patterns of Constructing Gender Relations and Female Scope for Action in Ancient Roman Sources By Anna Katharina Romund During the crisis of the Roman Republic, ancient sources mention a number of political interventions by women. The paper at hand seeks to investigate two of these occurences in which dreams motivated women to play an active role in political affairs. Cicero and Julius Obsequens report the dream of Caecilia Metella that instigated the repair of the temple of Juno Sospita in 90 BC. Nicolaus of Damascus, Velleius Paterculus, Valerius Maximus, Plutarch, Suetonius, Appian, Cassius Dio, and, again, Obsequens cover the dream of Caesar's wife Calpurnia in their works. According to them, the dream drove her to save Caesar from the imminent assassination in 44 BC. If we aim for a better understanding of the growing female scope for action, we will need to systematically analyse ancient authors’ personal conceptions of gender relations in a comparative way. Therefore, my paper examines the reports on Caecilia and Calpurnia in order to find recurring patterns that reflect the writers’ ideas of gender relations and gender hierarchies. A three-step analysis scheme will be created. 1) The model regards family roles as an indicator of the gender relationship discussed by the author. 2) The verbal or non-verbal mode of the woman’s intervention, whether of strong or weak intensity, mirrors the options of female action depending on that specific relationship. Furthermore, this relationship is defined by means of the depicted reaction attributed to the addressee. -

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood: A Novel of Ancient Rome Author: Steven Saylor Publisher: St. Martin’s Minotaur Year: 2000 ISBN: 9780312972967 You will be creating a magazine based on this novel. Be creative. Everything about your magazine should be centered around the theme of the novel. Your magazine must contain the following: Cover Table of Contents One: Crossword puzzle OR Word search OR Cryptogram At least 6 (six) news articles which may consist of character interviews, background on the time period, slave/master relationship, Roman law, etc. It is not necessary to interview Saylor. One of the following: horoscopes (relevant to the novel), cartoons (relevant to the novel), recipes (relevant to the novel), want ads (relevant to the novel), general advertisements for products/services (relevant to the novel). There must be no “white/blank” space in the magazine. It must be laid out and must look like a magazine and not just pages stapled together. This must be typed and neatly done. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. Due date: September 1, 2016. Thank you. SUMMER 2016 LATIN II GRADE 10: Amsco Workbook: Work on the review sections after verbs, nouns and adjectives. Complete all mastery exercises on pp. 36-39, 59-61, 64-66, 92-95, 102-104. Please be sure to study all relevant vocab in these mastery exercises. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. -

Mercury (Mythology) 1 Mercury (Mythology)

Mercury (mythology) 1 Mercury (mythology) Silver statuette of Mercury, a Berthouville treasure. Ancient Roman religion Practices and beliefs Imperial cult · festivals · ludi mystery religions · funerals temples · auspice · sacrifice votum · libation · lectisternium Priesthoods College of Pontiffs · Augur Vestal Virgins · Flamen · Fetial Epulones · Arval Brethren Quindecimviri sacris faciundis Dii Consentes Jupiter · Juno · Neptune · Minerva Mars · Venus · Apollo · Diana Vulcan · Vesta · Mercury · Ceres Mercury (mythology) 2 Other deities Janus · Quirinus · Saturn · Hercules · Faunus · Priapus Liber · Bona Dea · Ops Chthonic deities: Proserpina · Dis Pater · Orcus · Di Manes Domestic and local deities: Lares · Di Penates · Genius Hellenistic deities: Sol Invictus · Magna Mater · Isis · Mithras Deified emperors: Divus Julius · Divus Augustus See also List of Roman deities Related topics Roman mythology Glossary of ancient Roman religion Religion in ancient Greece Etruscan religion Gallo-Roman religion Decline of Hellenistic polytheism Mercury ( /ˈmɜrkjʉri/; Latin: Mercurius listen) was a messenger,[1] and a god of trade, the son of Maia Maiestas and Jupiter in Roman mythology. His name is related to the Latin word merx ("merchandise"; compare merchant, commerce, etc.), mercari (to trade), and merces (wages).[2] In his earliest forms, he appears to have been related to the Etruscan deity Turms, but most of his characteristics and mythology were borrowed from the analogous Greek deity, Hermes. Latin writers rewrote Hermes' myths and substituted his name with that of Mercury. However, there are at least two myths that involve Mercury that are Roman in origin. In Virgil's Aeneid, Mercury reminds Aeneas of his mission to found the city of Rome. In Ovid's Fasti, Mercury is assigned to escort the nymph Larunda to the underworld. -

ARCTOS Acta Philologica Fennica

ARCTOS Acta Philologica Fennica VOL. LI HELSINKI 2017 INDEX Heikki Solin Rolf Westman in Memoriam 9 Ria Berg Toiletries and Taverns. Cosmetic Sets in Small 13 Houses, Hospitia and Lupanaria at Pompeii Maurizio Colombo Il prezzo dell'oro dal 300 al 325/330 41 e ILS 9420 = SupplIt V, 253–255 nr. 3 Lee Fratantuono Pallasne Exurere Classem: Minerva in the Aeneid 63 Janne Ikäheimo Buried Under? Re-examining the Topography 89 Jari-Matti Kuusela & and Geology of the Allia Battlefield Eero Jarva Boris Kayachev Ciris 204: an Emendation 111 Olli Salomies An Inscription from Pheradi Maius in Africa 115 (AE 1927, 28 = ILTun. 25) Umberto Soldovieri Una nuova dedica a Iuppiter da Pompei e l'origine 135 di L. Ninnius Quadratus, tribunus plebis 58 a.C. Divna Soleil Héraclès le premier mélancolique : 147 Origines d'une figure exemplaire Heikki Solin Analecta epigraphica 319–321 167 Holger Thesleff Pivotal Play and Irony in Platonic Dialogues 179 De novis libris iudicia 220 Index librorum in hoc volumine recensorum 277 Libri nobis missi 283 Index scriptorum 286 Arctos 51 (2017) 63–88 PALLASNE EXURERE CLASSEM: MINERVA IN THE AENEID Lee Fratantuono The goddess Minerva is a key figure in the theology of Virgil's Aeneid, though there has been relatively little written to explicate all of the scenes in the epic in which she plays a part or receives a reference.1 The present study seeks to provide a commentary on every mention of Pallas Athena/Minerva in Virgil's poetic corpus, with the intention of illustrating how the goddess plays a crucial role in the unfolding drama of the transition from a Trojan to an Italian identity for the future Rome, and in particular how the Volscian heroine Camilla serves as a mortal incarnation of the Minerva who was a patroness of battles and the military arts. -

Reading Death in Ancient Rome

Reading Death in Ancient Rome Reading Death in Ancient Rome Mario Erasmo The Ohio State University Press • Columbus Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Erasmo, Mario. Reading death in ancient Rome / Mario Erasmo. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1092-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1092-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Death in literature. 2. Funeral rites and ceremonies—Rome. 3. Mourning cus- toms—Rome. 4. Latin literature—History and criticism. I. Title. PA6029.D43E73 2008 870.9'3548—dc22 2008002873 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1092-5) CD-ROM (978-0-8142-9172-6) Cover design by DesignSmith Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI 39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents List of Figures vii Preface and Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION Reading Death CHAPTER 1 Playing Dead CHAPTER 2 Staging Death CHAPTER 3 Disposing the Dead 5 CHAPTER 4 Disposing the Dead? CHAPTER 5 Animating the Dead 5 CONCLUSION 205 Notes 29 Works Cited 24 Index 25 List of Figures 1. Funerary altar of Cornelia Glyce. Vatican Museums. Rome. 2. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus. Vatican Museums. Rome. 7 3. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus (background). Vatican Museums. Rome. 68 4. Epitaph of Rufus. -

Roman Domestic Religion : a Study of the Roman Lararia

ROMAN DOMESTIC RELIGION : A STUDY OF THE ROMAN LARARIA by David Gerald Orr Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland in partial fulfillment of the requirements fo r the degree of Master of Arts 1969 .':J • APPROVAL SHEET Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia Name of Candidate: David Gerald Orr Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis and Abstract Approved: UJ~ ~ J~· Wilhelmina F. {Ashemski Professor History Department Date Approved: '-»( 7 ~ 'ii, Ii (, J ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia David Gerald Orr, Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis directed by: Wilhelmina F. Jashemski, Professor This study summarizes the existing information on the Roman domestic cult and illustrates it by a study of the arch eological evidence. The household shrines (lararia) of Pompeii are discussed in detail. Lararia from other parts of the Roman world are also studied. The domestic worship of the Lares, Vesta, and the Penates, is discussed and their evolution is described. The Lares, protective spirits of the household, were originally rural deities. However, the word Lares was used in many dif ferent connotations apart from domestic religion. Vesta was closely associated with the family hearth and was an ancient agrarian deity. The Penates, whose origins are largely un known, were probably the guardian spirits of the household storeroom. All of the above elements of Roman domestic worship are present in the lararia of Pompeii. The Genius was the living force of a man and was an important element in domestic religion. -

3274 Myths and Legends of Ancient Rome

MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF ANCIENT ROME CFE 3274V OPEN CAPTIONED UNITED LEARNING INC. 1996 Grade Levels: 6-10 20 minutes 1 Instructional Graphic Enclosed DESCRIPTION Explores the legend of Romulus and Remus, twin boys who founded Rome on seven hills. Briefly relates how Perseus, son of Jupiter, used his shield as a mirror to safely slay Medusa, a monster who turned anyone who looked on her to stone. Recounts the story of Psyche and Cupid, a story of broken promises and forgiveness. Each legend ends with discussion questions. Animated. INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS · To depict three Roman myths. · To enhance a unit on Roman mythology. · To show how the Romans explained natural phenomena and human behavior. · To show that human nature remains the same throughout the ages. BEFORE SHOWING 1. Read the CAPTION SCRIPT to determine unfamiliar vocabulary and language concepts. 2. Discuss the concept of myths: a. As a way of explaining and rationalizing natural phenomena. b. As stories of the heroic deeds and adventures of mortals with semidivine parentage. c. As stories of a large family of quarrelsome gods and goddesses. 3. Explain that the video shows three different Roman myths. a. Using a time line, explain that Roman mythology appeared after Greek mythology. b. Display a list of gods and goddesses and their Roman and Greek names. c. Explain there are many variations of the same myths. 4. Display a family tree of the Roman gods and goddesses. 1 a. Include pictures of monsters such as Medusa and Cerberus. b. Refer to the tree as characters appear in the video.