Reciprocity and the Chaos/Order Opposition in Virgil's Aeneid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apuleius's Story of Cupid and Psyche and the Roman Law of Marriage" Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), Vol

Georgetown University Institutional Repository http://www.library.georgetown.edu/digitalgeorgetown The author made this article openly available online. Please tell us how this access affects you. Your story matters. OSGOOD, J. "Nuptiae Iure Civili Congruae: Apuleius's Story of Cupid and Psyche and the Roman Law of Marriage" Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), Vol. 136, No. 2 (Autumn, 2006), pp. 415-441 Collection Permanent Link: http://hdl.handle.net/10822/555440 © 2006 The John Hopkins University Press This material is made available online with the permission of the author, and in accordance with publisher policies. No further reproduction or distribution of this copy is permitted by electronic transmission or any other means. Transactionsof the American Philological Association 136 (2006) 415-441 Nuptiae lure Civili Congruae: Apuleius'sStory of Cupid and Psyche and the Roman Lawof Marriage JOSIAH OSGOOD GeorgetownUniversity SUMMARY: Socialhistorians, despite showing greatinterest in Apuleius'sMeta- morphoses,have tended to ignorethe novel'sembedded tale of Cupidand Psycheon the groundsthat it is purelyimaginary. This paperdemonstrates that Apuleiusin fact refersthroughout his story to realRoman practices, especially legal practices-most conspicuousare the frequentreferences to the Romanlaw of marriage.A carefulexamination of severalpassages thus shows how knowl- edge of Romanlaw, it turns out, enhancesthe reader'spleasure in Apuleius's story.The paperconcludes by exploringthe connectionsbetween Apuleius's fairytaleand the accountof his own marriageto AemiliaPudentilla in his ear- lier work,the Apologia.Apuleius seems to be recalling,playfully, his own earlier legal success.At the same time, both works suggestthat legal problemsarose in Romanfamilies not becauseof the actions of any officialenforcers, but rather appealto the law by particularfamily members. -

A Study of the Cupid and Psyche Myth, with Particular Reference to C.S

Inklings Forever Volume 7 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Seventh Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Article 21 Lewis & Friends 6-3-2010 Tale as Old as Time: A Study of the Cupid and Psyche Myth, with Particular Reference to C.S. Lewis's Till We Have Faces John Stanifer Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Stanifer, John (2010) "Tale as Old as Time: A Study of the Cupid and Psyche Myth, with Particular Reference to C.S. Lewis's Till We Have Faces," Inklings Forever: Vol. 7 , Article 21. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol7/iss1/21 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tale as Old as Time: A Study of the Cupid and Psyche Myth, with Particular Reference to C.S. Lewis's Till We Have Faces Cover Page Footnote This essay is available in Inklings Forever: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol7/iss1/21 INKLINGS FOREVER, Volume VII A Collection of Essays Presented at the Seventh FRANCES WHITE COLLOQUIUM on C.S. LEWIS & FRIENDS Taylor University 2010 Upland, Indiana Tale as Old as Time A Study of the Cupid & Psyche Myth, with Particular Reference to C.S. -

Etruscans in the Context of European Identity

Phasis 15-16, 2012-2013 Ekaterine Kobakhidze (Tbilisi) Etruscans in the Context of European Identity The so-called cultural factor has a decisive role in European identity. It is common knowledge that the legacy of Antiquity made a significant contribution to shape it. Numerous fundamental studies have been devoted to the role of the ancient civilisation in the formation of European culture. However, the importance of the cultures, which made their contributions to the process of shaping European identity by making an impact on the ancient Greek and Roman world directly or via Graeca or via Roma, have not been given sufficient attention. In this regard, the Etruscan legacy is one of the most noteworthy. Pierre Grimal wrote in this connection that the Etruscan civilisation “played the same role ... in the history of Italy as the Cretan civilisation played in shaping the Greek world.“1 At the same time, the Etruscan civilisation proper emerged based on the archaic roots of Mediterranean cultures and, becoming, like the Greek civilisation, the direct heritor of the so-called Mediterranean substratum, which it elevated to new heights thanks to its own innovations and interpretations, it fulfilled an important function of a cultural mediator in the history of the nations of the new world. This is precisely what Franz Altheim meant, noting that “the importance of the Etruscan civilisation lies first and foremost in its cultural mediation.”2 As noted above, in addition, Etruscans introduced a lot of innovations and it is noteworthy that they were made in numerous important spheres, which we are going to discuss in detail below. -

(Leviticus 10:6): on Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible

1 “Do not bare your heads and do not rend your clothes” (Leviticus 10:6): On Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible Yael Shemesh, Bar Ilan University Many agree today that objective research devoid of a personal dimension is a chimera. As noted by Fewell (1987:77), the very choice of a research topic is influenced by subjective factors. Until October 2008, mourning in the Bible and the ways in which people deal with bereavement had never been one of my particular fields of interest and my various plans for scholarly research did not include that topic. Then, on October 4, 2008, the Sabbath of Penitence (the Sabbath before the Day of Atonement), my beloved father succumbed to cancer. When we returned home after the funeral, close family friends brought us the first meal that we mourners ate in our new status, in accordance with Jewish custom, as my mother, my three brothers, my father’s sisters, and I began “sitting shivah”—observing the week of mourning and receiving the comforters who visited my parent’s house. The shivah for my father’s death was abbreviated to only three full days, rather than the customary week, also in keeping with custom, because Yom Kippur, which fell only four days after my father’s death, truncated the initial period of mourning. Before my bereavement I had always imagined that sitting shivah and conversing with those who came to console me, when I was so deep in my grief, would be more than I could bear emotionally and thought that I would prefer for people to leave me alone, alone with my pain. -

Agorapicbk-15.Pdf

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 1s Prepared by Fred S. Kleiner Photographs by Eugene Vanderpool, Jr. Produced by The Meriden Gravure Company, Meriden, Connecticut Cover design: Coins of Gela, L. Farsuleius Mensor, and Probus Title page: Athena on a coin of Roman Athens Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1975 1. The Agora in the 5th century B.C. HAMMER - PUNCH ~ u= REVERSE DIE FLAN - - OBVERSE - DIE ANVIL - 2. Ancient method of minting coins. Designs were cut into two dies and hammered into a flan to produce a coin. THEATHENIAN AGORA has been more or less continuously inhabited from prehistoric times until the present day. During the American excava- tions over 75,000 coins have been found, dating from the 6th century B.c., when coins were first used in Attica, to the 20th century after Christ. These coins provide a record of the kind of money used in the Athenian market place throughout the ages. Much of this money is Athenian, but the far-flung commercial and political contacts of Athens brought all kinds of foreign currency into the area. Other Greek cities as well as the Romans, Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Turks have left their coins behind for the modern excavators to discover. Most of the coins found in the excavations were lost and never recovered-stamped into the earth floor of the Agora, or dropped in wells, drains, or cisterns. Consequently, almost all the Agora coins are small change bronze or copper pieces. -

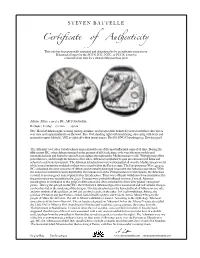

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Rome. the Etymological Origins

ROME.THE ETYMOLOGICAL ORIGINS Enrique Cabrejas — Director Linguistic Studies, Regen Palmer (Barcelona, Spain) E-mail: [email protected] The name of Rome was always a great mystery. Through this taxonomic study of Greek and Latin language, Enrique Cabrejas gives us the keys and unpublished answers to understand the etymology of the name. For thousands of years never came to suspect, including about the founder Romulus the reasons for the name and of his brother Remus, plus the unknown place name of the Lazio of the Italian peninsula which housed the foundation of ancient Rome. Keywords: Rome, Romulus, Remus, Tiber, Lazio, Italy, Rhea Silvia, Numitor, Amulio, Titus Tatius, Aeneas, Apollo, Aphrodite, Venus, Quirites, Romans, Sabines, Latins, Ἕλενος, Greeks, Etruscans, Iberians, fortuitus casus, vis maior, force majeure, rape of the Sabine, Luperca, Capitoline wolf, Palladium, Pallas, Vesta, Troy, Plutarch, Virgil, Herodotus, Enrique Cabrejas, etymology, taxonomy, Latin, Greek, ancient history , philosophy of language, acronyms, phrases, grammar, spelling, epigraphy, epistemology. Introduction There are names that highlight by their size or their amazing story. And from Rome we know his name, also history but what is the meaning? The name of Rome was always a great mystery. There are numerous and various hypotheses on the origin, list them again would not add any value to this document. My purpose is to reveal the true and not add more conjectures. Then I’ll convey an epistemology that has been unprecedented for thousands of years. So this theory of knowledge is an argument that I could perfectly support empirically. Let me take that Rome was founded as a popular legend tells by the brothers Romulus and Remus, suckled by a she-wolf, and according to other traditions by Romulus on 21 April 753 B.C. -

Aeneidic and Odyssean Patterns of Escape and Release in Tolkien's "The Fall of Gondolin" and the Return of the King

Volume 18 Number 2 Article 1 Spring 4-15-1992 Aeneidic and Odyssean Patterns of Escape and Release in Tolkien's "The Fall of Gondolin" and The Return of the King David Greenman Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Greenman, David (1992) "Aeneidic and Odyssean Patterns of Escape and Release in Tolkien's "The Fall of Gondolin" and The Return of the King," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 18 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol18/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Sees classical influence in the quest patterns of olkienT ’s heroes. Tuor fits the pattern of Aeneas (the Escape Quest) and the hobbits in Return of the King follow that of Odysseus (the Return Quest). -

Let's Think About This Reasonably: the Conflict of Passion and Reason

Let’s Think About This Reasonably: The Conflict of Passion and Reason in Virgil’s The Aeneid Scott Kleinpeter Course: English 121 Honors Instructor: Joan Faust Essay Type: Poetry Analysis It has long been a philosophical debate as to which is more important in human nature: the ability to feel or the ability to reason. Both functions are integral in our composition as balanced beings, but throughout history, some cultures have invested more importance in one than the other. Ancient Rome, being heavily influenced by stoicism, is probably the earliest example of a society based fundamentally on reason. Its most esteemed leaders and statesmen such as Cicero and Marcus Aurelius are widely praised today for their acumen in affairs of state and personal ethics which has survived as part of the classical canon. But when mentioning the classical canon, and the argument that reason is essential to civilization, a reader need not look further than Virgil’s The Aeneid for a more relevant text. The Aeneid’s protagonist, Aeneas, is a pious man who relies on reason instead of passion to see him through adversities and whose actions are foiled by a cast of overly passionate characters. Personages such as Dido and Juno are both portrayed as emotionally-laden characters whose will is undermined by their more rational counterparts. Also, reason’s importance is expressed in a different way in Book VI when Aeneas’s father explains the role reason will play in the future Roman Empire. Because The Aeneid’s antagonists are capricious individuals who either die or never find contentment, the text very clearly shows the necessity of reason as a human trait for survival and as a means to discover lasting happiness. -

Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna

Brief Chronicles IV (2012-13) 89 Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna: A Study in Jacobean Literary Form Roger Stritmatter his article investigates the presence of a concealed and previously undetected numerical symbolism in a Stuart-era emblem book, Henry TPeacham’s Minerva Britanna (1611). Although alien to modern conceptions of art, emblem books constitute one of the most widely published and popular genres in early modern book production. Drawing from an eclectic tradition of literary, religious, and iconological traditions, the emblem book combined words and images into complex patterns of signification, often of a markedly didactic character. Popular in all the European vernaculars, it appealed to a wide range of Renaissance readers, from the nearly illiterate (by virtue of its illustrated nature) to the most erudite (by virtue of its reputation for dazzling displays of intellectual and aesthetic virtuosity). By convention the emblem was divided into three parts: superscriptio, pictura, and subscriptio: the superscriptio was the short legend or motto that typically appeared at the top of the page; below it appeared the pictura – the emblem per se – followed by the subscriptio, a longer responsive analysis, usually written in verse, which completed the design. While emblem book scholars still debate the exact relationship between the three parts – and no doubt individual emblem writers themselves sometimes conceived of it in different ways, Deitrich Walter Jöns’ definition constitutes a useful and standard point -

The Architecture of Roman Temples

P1: JzL 052181068XAgg.xml CB751B/Stamper 0 521 81068 X August 28, 2004 17:30 The Architecture of Roman Temples - The Republic to the Middle Empire John W. Stamper University of Notre Dame iii P1: JzL 052181068XAgg.xml CB751B/Stamper 0 521 81068 X August 28, 2004 17:30 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C John W. Stamper 2005 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2005 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typefaces Bembo 11/14 pt., Weiss, Trajan, and Janson System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Stamper, John W. The architecture of Roman temples : the republic to the middle empire / John W. Stamper. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-521-81068-x 1. Temples, Roman – Italy – Rome. 2. Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus (Rome, Italy) 3. Architecture, Roman – Italy – Rome – Influence. 4. Rome (Italy) -

Aeneid 7 Page 1 the BIRTH of WAR -- a Reading of Aeneid 7 Sara Mack

Birth of War – Aeneid 7 page 1 THE BIRTH OF WAR -- A Reading of Aeneid 7 Sara Mack In this essay I will touch on aspects of Book 7 that readers are likely either to have trouble with (the Muse Erato, for one) or not to notice at all (the founding of Ardea is a prime example), rather than on major elements of plot. I will also look at some of the intertexts suggested by Virgil's allusions to other poets and to his own poetry. We know that Virgil wrote with immense care, finishing fewer than three verses a day over a ten-year period, and we know that he is one of the most allusive (and elusive) of Roman poets, all of whom wrote with an eye and an ear on their Greek and Roman predecessors. We twentieth-century readers do not have in our heads what Virgil seems to have expected his Augustan readers to have in theirs (Homer, Aeschylus, Euripides, Apollonius, Lucretius, and Catullus, to name just a few); reading the Aeneid with an eye to what Virgil has "stolen" from others can enhance our enjoyment of the poem. Book 7 is a new beginning. So the Erato invocation, parallel to the invocation of the Muse in Book 1, seems to indicate. I shall begin my discussion of the book with an extended look at some of the implications of the Erato passage. These difficult lines make a good introduction to the themes of the book as a whole (to the themes of the whole second half of the poem, in fact).