(Leviticus 10:6): on Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

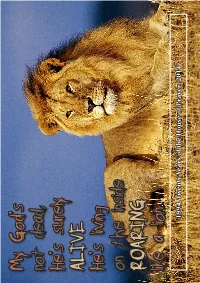

My God's Not Dead, He's Surely Alive He's Living on the Inside Roaring

My God’s not dead, He’s surely ALIVE He’s living on the inside ROARING like a lion 1994 Twenty Years of the House of Prayer 2014 - God’s not Dead Syria Jesus abandoned the changes that have The news this month We have included a taken place in Ireland has been dominated piece from a blog we in recent years and how by the wars in Palestine came across from a our society is becoming and Israel and in Syria monastery in County more Godless than ever and Iraq. We have been Meath. The prior was before. E horrified by images from told of an auction taking Twenty Years Syria of Christians, men, place near the monastery Our theme of twenty women and children, which included some years of the House of D being beheaded and religious artefacts. On Prayer also continues crucified because they going to investigate, he with two articles. One refuse to abandon was horrified to find that reflects on the early days I their faith and convert there was a tabernacle here in the House and to Islam. Harrowing with two Hosts still another talks about the images have been inside! music and how the Music T beamed across the world God’s Not Dead Ministry has evolved of children, beheaded, A couple of articles this over the years in to what maimed and their heads month are on the theme is now SonLight. O put on sticks for all to of ‘God’s Not Dead.’ Ballad of a Viral Video see. This is nothing We recently watched a A servant recounts short of barbaric!! It film of this title here at her thoughts on the R greatly upset me to see the House of Prayer and viral video of Fr. -

Agorapicbk-15.Pdf

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 1s Prepared by Fred S. Kleiner Photographs by Eugene Vanderpool, Jr. Produced by The Meriden Gravure Company, Meriden, Connecticut Cover design: Coins of Gela, L. Farsuleius Mensor, and Probus Title page: Athena on a coin of Roman Athens Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1975 1. The Agora in the 5th century B.C. HAMMER - PUNCH ~ u= REVERSE DIE FLAN - - OBVERSE - DIE ANVIL - 2. Ancient method of minting coins. Designs were cut into two dies and hammered into a flan to produce a coin. THEATHENIAN AGORA has been more or less continuously inhabited from prehistoric times until the present day. During the American excava- tions over 75,000 coins have been found, dating from the 6th century B.c., when coins were first used in Attica, to the 20th century after Christ. These coins provide a record of the kind of money used in the Athenian market place throughout the ages. Much of this money is Athenian, but the far-flung commercial and political contacts of Athens brought all kinds of foreign currency into the area. Other Greek cities as well as the Romans, Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Turks have left their coins behind for the modern excavators to discover. Most of the coins found in the excavations were lost and never recovered-stamped into the earth floor of the Agora, or dropped in wells, drains, or cisterns. Consequently, almost all the Agora coins are small change bronze or copper pieces. -

Torah: Covenant and Constitution

Judaism Torah: Covenant and Constitution Torah: Covenant and Constitution Summary: The Torah, the central Jewish scripture, provides Judaism with its history, theology, and a framework for ethics and practice. Torah technically refers to the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). However, it colloquially refers to all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, also called the Tanakh. Torah is the one Hebrew word that may provide the best lens into the Jewish tradition. Meaning literally “instruction” or “guidebook,” the Torah is the central text of Judaism. It refers specifically to the first five books of the Bible called the Pentateuch, traditionally thought to be penned by the early Hebrew prophet Moses. More generally, however, torah (no capitalization) is often used to refer to all of Jewish sacred literature, learning, and law. It is the Jewish way. According to the Jewish rabbinic tradition, the Torah is God’s blueprint for the creation of the universe. As such, all knowledge and wisdom is contained within it. One need only “turn it and turn it,” as the rabbis say in Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) 5:25, to reveal its unending truth. Another classical rabbinic image of the Torah, taken from the Book of Proverbs 3:18, is that of a nourishing “tree of life,” a support and a salve to those who hold fast to it. Others speak of Torah as the expression of the covenant (brit) given by God to the Jewish people. Practically, Torah is the constitution of the Jewish people, the historical record of origins and the basic legal document passed down from the ancient Israelites to the present day. -

THRU the BIBLE EXPOSITION Ezekiel

THRU THE BIBLE EXPOSITION Ezekiel: Effective Ministry To The Spiritually Rebellious Part XXXIII: Illustrating Israel's Great Pain From God's Discipline (Ezekiel 24:15-27) I. Introduction A. When God disciplines man for sin, His discipline is very painful that it might produce the desired repentance. B. Ezekiel 24:15-27 provides an illustration of this truth, and we view this passage for our insight (as follows): II. Illustrating Israel's Great Pain From God's Discipline, Ezekiel 24:15-27. A. God made Ezekiel a moving illustration of the painful shock his fellow Hebrew captives would experience at the fall of Jerusalem in God's judgment, the destruction of their beloved temple and children, Ezek. 24:15-24: 1. After God's prophet in Ezekiel 24:1-14 announced that the Babylonian army had begun its siege of Jerusalem, the Lord told Ezekiel that He was going to take the delight of his eyes, Ezekiel's wife, away from him in death with a "blow," that is, to take her life very suddenly, Ezekiel 24:15-16a NIV. 2. Regardless of the intense shock of such event, Ezekiel was not to mourn or weep, not to let tears run from his eyes, but to sigh silently, to perform no public mourning act for the dead, Ezek. 24:16b-17a. Rather, he was to bind on his turban, put on his sandals, not cover the lower part of his face nor eat any food, highly unusual behavior for a man who had just tragically, suddenly lost his beloved wife, Ezekiel 24:17b NIV. -

Introduction to the Hebrew Bible Hb 510

1 INTRODUCTION TO THE HEBREW BIBLE HB 510 Instructor: Paul Kim Spring 2016 (Wednesdays 8:30 – 11:20 am) COURSE DESCRIPTION “For learning wisdom and discipline; for understanding words of discernment; for acquiring the discipline for success” (Prov 1:2) 1. This is an introduction to the study of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament, Hebrew Scriptures, or Tanak). We will attempt to acquire both broad and in-depth knowledge of the HB for a diverse, enriching, and thereby better understanding, appreciation, and application of it toward our life, ministry, and world. 2. In order to attain broad and in-depth understanding, this course aims at (a) acquainting the students with the basic data of biblical history and literature and (b) having them be exposed to and digest diverse critical and theological readings of the Bible, such as literary, historical, gender-oriented, ethnicity-oriented and Third World approaches in order that what is learned can become the ground for the students’ own interpretive appropriation (in reading and interpreting the Bible) in the contexts of multiple issues, concerns, and tasks of the church, as well as in incorporating into pastoral care and counseling. 3. For these goals, I would like us to pursue mutually open respect, disagreement, and dialogue among ourselves during lectures and discussions. I would like to encourage you not to be confined to one orientation or method but be willing to explore various angles, theories, and perspectives, even if your view may differ significantly. TEXTBOOKS “Of making many books, there is no end” (Eccl 12:12) Joel S. Kaminsky and Joel N. -

Domitian's Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome

Rising from the Ashes: Domitian’s Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome Lea K. Cline In the August 1888 edition of the Notizie degli Scavi, profes- on a base of two steps; it is a long, solid rectangle, 6.25 m sors Guliermo Gatti and Rodolfo Lanciani announced the deep, 3.25 m wide, and 1.26 m high (lacking its crown). rediscovery of a Domitianic altar on the Quirinal hill during These dimensions make it the second largest public altar to the construction of the Casa Reale (Figures 1 and 2).1 This survive in the ancient capital. Built of travertine and revet- altar, found in situ on the southeast side of the Alta Semita ted in marble, this altar lacks sculptural decoration. Only its (an important northern thoroughfare) adjacent to the church inscription identifies it as an Ara Incendii Neroniani, an altar of San Andrea al Quirinale, was not unknown to scholars.2 erected in fulfillment of a vow made after the great fire of The site was discovered, but not excavated, in 1644 when Nero (A.D. 64).7 Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini) and Gianlorenzo Bernini Archaeological evidence attests to two other altars, laid the foundations of San Andrea al Quirinale; at that time, bearing identical inscriptions, excavated in the sixteenth the inscription was removed to the Vatican, and then the and seventeenth centuries; the Ara Incendii Neroniani found altar was essentially forgotten.3 Lanciani’s notes from May on the Quirinal was the last of the three to be discovered.8 22, 1889, describe a fairly intact structure—a travertine block Little is known of the two other altars; one, presumably altar with remnants of a marble base molding on two sides.4 found on the Vatican plain, was reportedly used as building Although the altar’s inscription was not in situ, Lanciani refers material for the basilica of St. -

The Bible in Music

The Bible in Music 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb i 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM The Bible in Music A Dictionary of Songs, Works, and More Siobhán Dowling Long John F. A. Sawyer ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiiiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by Siobhán Dowling Long and John F. A. Sawyer All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dowling Long, Siobhán. The Bible in music : a dictionary of songs, works, and more / Siobhán Dowling Long, John F. A. Sawyer. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-8451-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-8452-6 (ebook) 1. Bible in music—Dictionaries. 2. Bible—Songs and music–Dictionaries. I. Sawyer, John F. A. II. Title. ML102.C5L66 2015 781.5'9–dc23 2015012867 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

Des Clitumnus (8,8) Und Des Lacus Vadimo (8,20)

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg ECKARD LEFÈVRE Plinius-Studien IV Die Naturauffassungen in den Beschreibungen der Quelle am Lacus Larius (4,30), des Clitumnus (8,8) und des Lacus Vadimo (8,20) Mit Tafeln XIII - XVI Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Gymnasium 95 (1988), S. [236] - 269 ECKARD LEFEVRE - FREIBURG I. BR. PLINIUS-STUDIEN IV Die Naturauffassung in den Beschreibungen der Quelle am Lacus Larius (4,30), des Clitumnus (8,8) und des Lacus Vadimo (8,20)* Mit Tafeln XIII-XVI quacumque enim ingredimur, in aliqua historia vestigium ponimus. Cic. De fin. 5,5 In seiner 1795 erschienenen Abhandlung Über naive und sentimen- talische Dichtung unterschied Friedrich von Schiller den mit der Natur in Einklang lebenden, den ‚naiven' Dichter (und Menschen) und den aus der Natur herausgetretenen, sich aber nach ihr zurücksehnenden, den ,sentimentalischen` Dichter (und Menschen). Der Dichter ist nach Schil- ler entweder Natur, oder er wird sie suchen. Im großen und ganzen war mit dieser Unterscheidung die verschiedene Ausprägung der griechischen und der modernen Dichtung gemeint. Schiller hat richtig gesehen, daß die Römer im Hinblick auf diese Definition den Modernen zuzuordnen sind': Horaz, der Dichter eines kultivierten und verdorbenen Weltalters, preist die ruhige Glückseligkeit in seinem Tibur, und ihn könnte man als den wahren Stifter dieser Diese Betrachtungen bilden zusammen mit den Plinius-Studien I-III (die in den Lite- raturhinweisen aufgeführt sind) eine Tetralogie zu Plinius' ästhetischer Naturauffas- sung. Dieses Thema ist hiermit abgeschlossen. [Inzwischen ist das interessante Buch von H. Mielsch, Die römische Villa. Architektur und Lebensform, München 1987, erschienen, in dem einiges zur Sprache kommt, was in dieser Tetralogie behandelt wird.] Auch in diesem Fall wurden die Briefe als eigenständige Kunstwerke ernst- genommen und jeweils als Ganzes der Interpretation zugrundegelegt. -

Church of Saint Edward the Confessor

Pastor: Church of MSGR. PAUL P. ENKE Saint Edward the Confessor Deacon: REV. MR. JOHN BARBOUR 785 NEWARK-GRANVILLE ROAD • GRANVILLE, OHIO 43023 PastorAL MINISTEr/r.C.I.A. WWW.SAINTEDWARDS.ORG PArISH School of rELIgion: 740-587-4160 MIKE MILLISOR [email protected] SARAH SWEEN [email protected] PArISH Office: 740-587-3254 [email protected] Office ManagEr: CHEryL BOGGESS, CPA [email protected] Office Staff: BARBARA HINTERSCHIED [email protected] ANNE ARNOLD [email protected] Youth MINISTEr: MarIssa EVERHart, 740-587-3254 [email protected] Preschool DIrector: ADRIENNE EVANS, 740-587-3275 [email protected] Maintenance: DIANE KINNEY, KEVIN KINNEY FLOYD LAHMON DIrector of Music: PAUL RADKOWSKI, 740-587-3254 [email protected] Baptismal CLASS: (Contact PArISH Office) PatrICIA BELHORN, 740-587-3254 MArrIAgE Preparation INventorY PrOgrAM DCN. JOHN AND CINDY BARBOUR, 740-587-3254 respect LIFE Committee: JOHN KOENIG, 740-587-0720 [email protected] PArISH Council: JOHN MartIN, 614-403-0567 Dominican Sisters of Peace [email protected] visits to SHUT-ins: CONFESSIONS: DIANE KINNEY, 740-587-4121 MASS SCHEDULE SUNDAY MASS SCHEDULE: SATURDAY: 4:00-4:30 P.M. Eucharistic ADOration: SATURDAY: 5:00 P.M. BULLETIN DEADLINE: KIM CHUPKA, 740-587-7067 SUNDAY: 8:15 A.M. Monday NOON [email protected] 10:45 A.M. PARISH OFFICE: KNIghts of Columbus: HOLY DAY MASS SCHEDULE: 740-587-3254 MIKE MaurER, 740-348-6377 [email protected] TBA IN BULLETIN FAX: WEEKDAY MASS SCHEDULE: Prayer CHAIN 740-587-0149 E-MAIL: CIndy KEndrICK, 740-366-2871 MONDAY-FRIDAY: [email protected] 9:00 A.M. -

June 7-25, 2020…..17 Days in Scandinavia with Dave Anderson

June 7-25, 2020…..17 days in Scandinavia with Dave Anderson Sunday June 7 Our tour begins with an evening flight from Chicago to Copenhagen Monday June 8 We arrive in Copenhagen, go to our hotel to freshen up and then we will stretch our legs on Copenhagen’s famous walking street. Dinner and overnight at our Copenhagen hotel. Tuesday, June 9 Today we will visit Roskilde, the incredible cathedral where Danish Kings and Queens are buried. We will stop at the famous mermaid statue in the Copenhagen harbor and a great fountain nearby. We will stop at two amazing Copenhagen cathedrals including the Gruntvig Cathedral. Dinner tonight in Tivoli Gardens, one of Europe’s most famous amusement parks. Same hotel. Wednesday, June 10 We head a little north of Copenhagen to the beautiful and massive Christian IV Castle. The castle tour will take two hours. After lunch we head east to Helsingør for a short ferry boat ride to Helsingborg, Sweden. After looking around the city center, we will travel to the very old Helsingborg suburb of Råå, where we will stay overnight at the Sundsgården Folkhögskola. Dinner and great accommodations. Sundsgården is a Chrsitian “folk high school” where Dave and Barb Anderson have stayed many times. Thursday, June 11 After breakfast, we will travel south to the great university city of Lund where we will visit the 1000-year old Lund Cathedral. We will have time to look in shops in Lund and have lunch there. Dave and Barb Anderson have hosted the Rökeblås (Röke is the village the founder of the band lived in and blås is the Sweden word for “blow”) band for ten US tours over the past 40 years. -

Kabbalah As a Shield Against the “Scourge” of Biblical Criticism: a Comparative Analysis of the Torah Commentaries of Elia Benamozegh and Mordecai Breuer

Kabbalah as a Shield against the “Scourge” of Biblical Criticism: A Comparative Analysis of the Torah Commentaries of Elia Benamozegh and Mordecai Breuer Adiel Cohen The belief that the Torah was given by divine revelation, as defined by Maimonides in his eighth principle of faith and accepted collectively by the Jewish people,1 conflicts with the opinions of modern biblical scholarship.2 As a result, biblical commentators adhering to both the peshat (literal or contex- tual) method and the belief in the divine revelation of the Torah, are unable to utilize the exegetical insights associated with the documentary hypothesis developed by Wellhausen and his school, a respected and accepted academic discipline.3 As Moshe Greenberg has written, “orthodoxy saw biblical criticism in general as irreconcilable with the principles of Jewish faith.”4 Therefore, in the words of D. S. Sperling, “in general, Orthodox Jews in America, Israel, and elsewhere have remained on the periphery of biblical scholarship.”5 However, the documentary hypothesis is not the only obstacle to the religious peshat commentator. Theological complications also arise from the use of archeolog- ical discoveries from the ancient Near East, which are analogous to the Torah and can be a very rich source for its interpretation.6 The comparison of biblical 246 Adiel Cohen verses with ancient extra-biblical texts can raise doubts regarding the divine origin of the Torah and weaken faith in its unique sanctity. The Orthodox peshat commentator who aspires to explain the plain con- textual meaning of the Torah and produce a commentary open to the various branches of biblical scholarship must clarify and demonstrate how this use of modern scholarship is compatible with his or her belief in the divine origin of the Torah. -

Musgrave, George. 2020. Avicii: True Stories - Review

Musgrave, George. 2020. Avicii: True Stories - Review. Dancecult Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture, 12(1), pp. 94-97. ISSN 1947-5403 [Article] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/28935/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] 94 Dancecult 12(1) Avicii: True Stories Dir. Levan Tsikurishvili USA: Black Dalmation Films, OPA People Production, Piece of Magic Entertainment, and SF Bio, 2017. <https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7357302/> <http://dx.doi.org/10.12801/1947-5403.2020.12.01.15> George Musgrave Goldsmiths, University of London (UK) University of Westminster (UK) It is extremely hard to review a documentary like Avicii: True Stories and disentangle myself from the research on mental health and the music industry which I have spent the last four years immersed in (Gross and Musgrave 2016; 2017; 2020). With almost every minute that passes of this profoundly sad, and at times chilling film, I found myself thinking that, in many respects, what I was watching was one of the most extreme case studies imaginable for the conceptual architecture we have developed to try and grapple with the potential for toxicity which a music career presents.