Mormon Intruders in Tonga: the Passport Act of 1922

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Pacific Islands

A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS I. C. Campbell A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Thi s One l N8FG-03S-LXLD A History of the Pacific Islands I. C. CAMPBELL University of California Press Berkeley • Los Angeles Copyrighted material © 1989 I. C. Campbell Published in 1989 in the United States of America by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles All rights reserved. Apart from any fair use for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, no part whatsoever may by reproduced by any process without the express written permission of the author and the University of California Press. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Campbell, LC. (Ian C), 1947- A history of the Pacific Islands / LC. Campbell, p. cm. "First published in 1989 by the University of Canterbury Press, Christchurch, New Zealand" — T.p. verso. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-520-06900-5 (alk. paper). — ISBN 0-520-06901-3 (pbk. alk. paper) 1. Oceania — History. I. Title DU28.3.C35 1990 990 — dc20 89-5235 CIP Typographic design: The Caxton Press, Christchurch, New Zealand Cover design: Max Hailstone Cartographer: Tony Shatford Printed by: Kyodo-Shing Loong Singapore C opy righted m ateri al 1 CONTENTS List of Maps 6 List of Tables 6 A Note on Orthography and Pronunciation 7 Preface. 1 Chapter One: The Original Inhabitants 13 Chapter Two: Austronesian Colonization 28 Chapter Three: Polynesia: the Age of European Discovery 40 Chapter Four: Polynesia: Trade and Social Change 57 Chapter Five: Polynesia: Missionaries and Kingdoms -

THE HISTORY of the TONGA and FISHING COOPERATIVES in BINGA DISTRICT 1950S-2015

FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY EMPOWERMENT OR CONTROL? : THE HISTORY OF THE TONGA AND FISHING COOPERATIVES IN BINGA DISTRICT 1950s-2015 BY HONOUR M.M. SINAMPANDE R131722P DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS IN PARTIAL FULLFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE HONOURS DEGREE IN HISTORY AT MIDLANDS STATE UNIVERSITY. NOVEMBER 2016 ZVISHAVANE: ZIMBABWE SUPERVISOR DR. T.M. MASHINGAIDZE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have supervised the student Honour M.M Sinampande (R131722P) dissertation entitled Empowerment or Control? : The history of the Tonga and fishing cooperatives in Binga District 1950-210 submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Arts in History Honours Degree offered by Midlands State University. Dr. T.M Mashingaidze ……………………… SUPERVISOR DATE …….……………………………………… …………………………….. CHAIRPERSON DATE ….………………………………………… …………………………….. EXTERNAL EXAMINER DATE DECLARATION I, Honour M.M Sinampande declare that, Empowerment or Control? : The history of the Tonga and fishing cooperatives in Binga District 1950s-2015 is my own work and it has never been submitted before any degree or examination in any other university. I declare that all sources which have been used have been acknowledged. I authorize the Midlands State University to lend this to other institution or individuals for purposes of academic research only. Honour M.M Sinampande …………………………………………… 2016 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my father Mr. H.M Sinampande and my mother Ms. J. Muleya for their inspiration, love and financial support throughout my four year degree programme. ABSTRACT The history of the Tonga have it that, the introduction of the fishing villages initially and then later the cooperative system in Binga District from the 1950s-2015 saw the Zambezi Tonga lose their fishing rights. -

The Schengen Acquis

The Schengen acquis integrated into the European Union ð 1 May 1999 Notice This booklet, which has been prepared by the General Secretariat of the Council, does not commit either the Community institutions or the governments of the Member States. Please note that only the text that shall be published in the Official Journal of the European Communities L 239, 22 September 2000, is deemed authentic. For further information, please contact the Information Policy, Transparency and Public Relations Division at the following address: General Secretariat of the Council Rue de la Loi 175 B-1048 Brussels Fax 32 (0)2 285 5332 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://ue.eu.int A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet.It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2001 ISBN 92-824-1776-X European Communities, 2001 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium 3 FOREWORD When the Amsterdam Treaty entered into force on 1 May 1999, cooperation measures hitherto in the Schengen framework were integrated into the European Union framework. The Schengen Protocol annexed to the Amsterdam Treaty lays down detailed arrangements for that integration process. An annex to the protocolspecifies what is meant by ‘Schengen acquis’. The decisions and declarations adopted within the Schengen institutional framework by the Executive Committee have never before been published. The GeneralSecretariat of the Councilhas decided to produce for those interested a collection of the Executive Committee decisions and declarations integrated by the Councildecision of 20 May 1999 (1999/435/EC). -

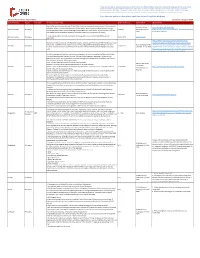

Airport Restrictions Information Updated 3 August 2020 If You Have

Please note, although we endeavour to provide you with the most up to date information derived from various third parties and sources, we cannot be held accountable for any inaccuracies or changes to this information. Inclusion of company information in this matrix does not imply any business relationship between the supplier and WFP / Logistics Cluster, and is used solely as a determinant of services, and capacities. Logistics Cluster /WFP maintain complete impartiality and are not in a position to endorse, comment on any company's suitability as a reputable service provider. If you have any updates to share, please email them to: [email protected] Airport Restrictions Information Updated 3 August 2020 State / Territory Airport ICAO Code Restrictions (Other Info) Restriction Period Source of Info URL / Remarks State of Emergency is extended until 30 July 2020. Color-coded system to guide response. Current level is American Samoa https://6fe16cc8-c42f-411f-9950- Code Blue. All entry permits suspended until further notice. All unnecessary outbound travel strongly American Samoa All airports 1-30 July Government, 1 July 4abb1763c703.filesusr.com/ugd/4bfff9_3514d6c2679d40408 discouraged. All travellers must provide negative COVID-19 test results within 72 hours before arrival. All 2020 e65df6b5bfc38e9.pdf non-medical personnel entering American Samoa are subject to full quarantine of 14 days. Travelers must adhere to mandatory COVID-19 testing upon arrival and complete full 14 days of American Samoa All airports 18 June UFN [email protected] quarantine. https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel- Australia’s borders are closed. Only Australian citizens, residents and immediate family members can travel coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19- to Australia. -

Cedaw Smokescreens: Gender Politics in Contemporary Tonga

CEDAW Smokescreens: Gender Politics in Contemporary Tonga Helen Lee Tonga remains one of only six countries that have not ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (cedaw), which was adopted in 1979 by the United Nations Gen- eral Assembly. In March 2015, the Tongan government made a commit- ment to the United Nations that it would finally ratify cedaw, albeit with some reservations. The prime minister, ‘Akilisi Pōhiva, called it “a historic day for all Tongans . in support of our endeavour to eliminate all forms of discrimination against women and girls” (Matangi Tonga 2015e).1 However, the decision to ratify was met with public protests and peti- tions, and in June, the Privy Council, headed by the king, announced that the proposed ratification was unconstitutional (P Fonua 2015), claiming that under clause 39 of Tonga’s 1875 Constitution, “only the King can lawfully make treaties with foreign states” (Radio New Zealand 2015b). This article asks why so many Tongans, both male and female, are against ratifying cedaw. I argue that their protests conceal much deeper anxieties about gender equality and, more broadly, about democracy and Tonga’s future. In order to understand this resistance to cedaw’s ratification, I explore key issues in Tonga’s contemporary gender politics, including women’s roles in leadership, the economy, and the family, as well as gov- ernment policies addressing gender equality. cedaw in Tonga Most Pacific nations have ratified or acceded to cedaw,2 beginning with New Zealand in 1985 and Sāmoa in 1992. The only remaining Pacific countries are Palau, which signed the convention in 2011 but has not for- mally ratified or acceded to it,3 and Tonga, which has not even signed the The Contemporary Pacic, Volume 29, Number 1, 66–90 © 2017 by University of Hawai‘i Press 66 lee • cedaw smokescreens 67 convention (United Nations 2016). -

The Impact of Westernization on Tongan Cultural Values Related to Business

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 5-2009 The mpI act of Westernization on Tongan Cultural Values Related to Business Lucas Nelson Ross Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the International Business Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Ross, Lucas Nelson, "The mpI act of Westernization on Tongan Cultural Values Related to Business" (2009). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 69. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/69 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF WESTERNIZATION ON TONGAN CULTURAL VALUES RELATED TO BUSINESS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Psychology Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Lucas Nelson Ross May 2009 THE IMPACT OF WESTERNIZATION ON TONGAN CULTURAL VALUES RELATED TO BUSINESS Date Recommended _April 30, 2009______ ______ Tony Paquin ___________________ Director of Thesis ______Betsy Shoenfelt__________________ ______Reagan Brown___________________ ____________________________________ Dean, Graduate Studies and Research Date ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank my thesis chair, Dr. Tony Paquin, for putting up with my awkward sentences, my lack of transitions, and my total disregard of conjunctive adverbs. I would also like thank the other members on my committee, Dr. Betsy Shoenfelt and Dr. Reagan Brown, for their support and input. Finally, I would like to thank my family for always accepting the “I have to work on my thesis” excuse. -

Decisions of the Executive Committee and the Central Group — Declarations of the Central Group

2. — DECISIONS OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE AND THE CENTRAL GROUP — DECLARATIONS OF THE CENTRAL GROUP 2.1. HORIZONTAL 2. — DECISIONS OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE AND THE CENTRAL GROUP 155 DECISION OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE of 14 December 1993 concerning the declarations by the ministers and State secretaries (SCH/Com-ex (93) 10) The Executive Committee, Having regard to Article 132 of the convention implementing the Schengen Agreement, HAS DECIDED AS FOLLOWS: the declarations by the ministers and State secretaries of 19 June 1992 (1) and 30 June 1993 regarding the bringing into force of the implementing convention and the fulfilment of the prerequisites are hereby confirmed. Paris, 14 December 1993 The Chairman A. LAMASSOURE (1) The declarations of 19 June 1992 have not been taken over in the acquis. 156 The Schengen acquis Annex Madrid, 30 June 1993 SCH/M (93) 14 DECLARATION OF THE MINISTERS AND STATE SECRETARIES 1. The ministers and State secretaries hereby agree to set the political goal of applying the 1990 Schengen Convention as of 1 December 1993. 2. The ministers and State secretaries note that the following preconditions have been fulfilled: — the common manual; — the arrangements for issuing the uniform visa and the common consular instructions on visas; — the examination of applications for asylum; — the airports, as agreed in the declaration of the ministers and State secretaries of 19 June 1992. Great progress has been made in respect of the other preconditions, which have already been fulfilled to such an extent that the said application ought to be possible as of 1 December 1993. -

Human Systems

Human Systems In the video below, Hans Rosling looks at the factors involved in demographic changes. This presentation demonstrates massive amounts of demographic data in 4 minutes to show 200 years of changing income and life expectancy around the world. Video 5.1: 200 Countries, 200 Years, 4 Minutes, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jbkSRLYSojo Having the data is not enough- there needs to be an enjoyable way to communicate the data. The data is shown on a graph which indicates life expectancy and income. Within this graph, we can see where poor and sick would be located and rich and healthy would be located. The regions he is looking at is Europe, Asia, the Americas, and Africa. This video is a very engaging and enjoyable way to understand global health and wealth patterns. Note: Income per person (GDP per capita) is adjusted for inflation and for differences in costs of living (purchasing power) across countries. You can play with the data yourself in Gapminder World. Introduction The study of the Earth’s Human Systems is a complex topic. Over 7 billion people inhabit Earth and each are part of multiple human systems. Human systems, simply put, are the patterns and relationships among culture, economies, politics, and demographics. It is easy to make generalizations and oversimplify these systems (and the people in them), but this often leads to misunderstandings, stereotypes, and even prejudice. Our job as geography educators is to eliminate these misunderstandings and lead our students to a deeper understanding of the rich cultural mosaic of our global population. -

CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper

SAE./No.22/December 2014 Studies in Applied Economics CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise & Center for Financial Stability Currency Board Financial Statements First version, December 2014 By Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Paper and accompanying spreadsheets copyright 2014 by Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler. All rights reserved. Spreadsheets previously issued by other researchers are used by permission. About the series The Studies in Applied Economics of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise are under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute ([email protected]). This study is one in a series on currency boards for the Institute’s Currency Board Project. The series will fill gaps in the history, statistics, and scholarship of currency boards. This study is issued jointly with the Center for Financial Stability. The main summary data series will eventually be available in the Center’s Historical Financial Statistics data set. About the authors Nicholas Krus ([email protected]) is an Associate Analyst at Warner Music Group in New York. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics from The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he also worked as a research assistant at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise and did most of his research for this paper. Kurt Schuler ([email protected]) is Senior Fellow in Financial History at the Center for Financial Stability in New York. -

Information to Users

The political ecology of a Tongan village Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Stevens, Charles John, 1950- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 00:11:56 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290684 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper lefr-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

The Tongan Pentecost of 1834 : a Revival in the Kingdom of Tonga

ABSTRACT The Tongan Pentecost of 1834: A Revival in the Kingdom of Tonga: A Possible Key for Renewal and Unity for the Tongan Church Today by Manase Koloamatangi Tafea The Tongan Pentecost was a revival that took place in the kingdom of Tonga ' when Aisea Vovole Latu preached in the village of 'Utui in 1 834. During the service the Holy Spirit moved in a mighty way empowering the congregation until prayers, singing, and testimonies began in such a way that the preacher could not control them. The fire of the Holy Spirit which started in 'Utui spread within a month to all the islands in the Tonga group. The king and the people were converted, resulting in unity and a new motivation for mission and evangelism. After a year the momentum of this Tongan Pentecost spread to the other Pacific islands, first to the Fijian and Samoan groups. Although the Tongan people today tend to remember the history of the 1 834 Tongan Pentecost, their experience of the Holy Spirit is, by and large, limited and perfunctory resulting in division and lack of purpose. Therefore, the purpose of this project dissertation is to rediscover how the Tongan Pentecost of 1 834 affected the Tongan worldview, establishing a sense of unity and mission, and to see if a fresh encounter with the Holy Spirit can renew that sense of unity and mission today. In this project I examined the history of the 1834 experience. With a questionnaire I discovered: (1) that the experience actually happened; (2) that the experience created unity and purpose; and, (3) that the experience could be renewed so the Tongan church can be reunited and motivated toward mission and evangelism. -

Of Tongan Gods

TAPUA: “POLISHED IVORY SHRINES” OF TONGAN GODS FERGUS CLUNIE Sainsbury Research Unit, University of East Anglia Thanks to John Thomas and his fellow missionaries it is known “whales’ teeth” or “polished ivory shrines” were associated with Tongan gods. They failed to elaborate on their form or say how they worked, however, while those they sent “home” have largely lost their identities so no doubt mostly lie in unmarked graves in Fijian collections. In Tonga, meanwhile, because they were kept so closely secluded few but their assigned keepers, priests and makers saw them, knowledge of them has been lost. These anonymous, effectively nondescript objects or tapua have attracted little scholarly attention. That is no longer so, however, for a smoke-stained whale-bone crescent dedicated to a Tongan god has established that they are indistinguishable from symmetrically crescentic tabuabuli, historically the most esteemed form of Fijian tabua. This realisation led to the central issue addressed here: that of a close spiritual and historical relationship between Fijian tabuabuli and Tongan tapua. Because the evidence is so scattered, and the way in which it accrues so diagnostic of the character of the tapua, I will follow its spoor forward from European contact, taking and assessing contributions as they come. Initially, Figure 1. Tabua shaped into crescentic form were termed tabuabuli (buli: ‘formed’) to distinguish them from Fijian-made tabua, which retain the natural form of the whale tooth. Fijian tabuabuli are indistinguishable from Tongan tapua. Collected in Fiji by Baron von Hügel, 1875-77. MAA Z3026. (© Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge.) 161 162 Tapua : “Polished Ivory Shrines” of Tongan Gods this will entail reviewing indirect 18th century evidence.