The D.C. Freeway Revolt and the Coming of Metro Part 6 a New Administration Takes Over

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider There are so many things to do when visiting D.C., many for free, and here are a few you may have not done before. They may make it worthwhile to come to D.C. early or to stay to the end of the weekend. Getting to the Sites: • D.C. Sites and the Pentagon: Metro is a way around town. The hotel is four minutes from the Metro’s Mt. Vernon Square/7th St.-Convention Center Station. Using Metro or walking, or a combination of the two (or a taxi cab) most D.C. sites and the Pentagon are within 30 minutes or less from the hotel.1 Googlemaps can help you find the relevant Metro line to use. Circulator buses, running every 10 minutes, are an inexpensive way to travel to and around popular destinations. Routes include: the Georgetown-Union Station route (with a stop at 9th and New York Avenue, NW, a block from the hotel); and the National Mall route starting at nearby Union Station. • The Mall in particular. Many sites are on or near the Mall, a five-minute cab ride or 17-minute walk from the hotel going straight down 9th Street. See map of Mall. However, the Mall is huge: the Mall museums discussed start at 3d Street and end at 14th Street, and from 3d Street to 14th Street is an 18-minute walk; and the monuments on the Mall are located beyond 14th Street, ending at the Lincoln Memorial at 23d Street. -

East-Download The

TIDAL BASIN TO MONUMENTS AND MUSEUMS Outlet Bridge TO FRANKLIN L’ENFANT DELANO THOMAS ROOSEVELT ! MEMORIAL JEFFERSON e ! ! George ! # # 14th STREET !!!!! Mason Park #! # Memorial MEMORIAL # W !# 7th STREET ! ! # Headquarters a ! te # ! r ## !# !# S # 395 ! t # !! re ^ !! e G STREET ! OHIO DRIVE t t ! ! # e I Street ! ! ! e ! ##! tr # ! !!! S # th !!# # 7 !!!!!! !! K Street Cuban ! Inlet# ! Friendship !!! CASE BRIDGE## SOUTHWEST Urn ! # M Bridge ! # a # ! # in !! ! W e A !! v ! e ! ! ! n ! ! u East Potomac !!! A e 395 ! !! !!!!! ^ ! Maintenance Yard !! !!! ! !! ! !! !!!! S WATERFRONT ! e ! !! v ! H 6 ri ! t ! D !# h e ! ! S ! y # I MAINE AVENUE Tourmobile e t George Mason k ! r ! c ! ! N e !! u ! e ! B East Potomac ! Memorial !!! !!! !! t !!!!! G Tennis Center WASHINGTON! !! CHANNEL I STREET ##!! !!!!! T !"!!!!!!! !# !!!! !! !"! !!!!!! O Area!! A Area B !!! ! !! !!!!!! N ! !! U.S. Park ! M S !! !! National Capital !!!!!#!!!! ! Police Region !!!! !!! O !! ! Headquarters Headquarters hi !! C !!!! o !!! ! D !!!!! !! Area C riv !!!!!!! !!!! e !!!!!! H !! !!!!! !!O !! !! !h ! A !! !!i ! ! !! !o! !!! Maine !!!D ! ! !!r !!!! # Lobsterman !!iv ! e !! N !!!!! !! Memorial ! ! !!" ! WATER STREET W !!! !! # ! ! N a ! ! ! t !! ! !! e !! ##! r !!!! #! !!! !! S ! ! !!!!!!! ! t !!! !! ! ! E r !!! ! !!! ! ! e !!!! ! !!!!!! !!! e ! #!! !! ! ! !!! t !!!!!#!! !!!!! BUCKEYE DRIVE Pool !! L OHIO #!DRIVE! !!!!! !!! #! !!! ! Lockers !!!## !! !!!!!!! !! !# !!!! ! ! ! ! !!!!! !!!! !! !!!! 395 !!! #!! East Potomac ! ! !! !!!!!!!!!!!! ! National Capital !!!! ! ! -

NTSB Accident Report

TRANSPORTATION SAFETII! BOARD AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT l$EPOfiT,, . !!;, , I,_ .: I ‘/ AlR FLORIIDA, INC. -: BOEING 737-222, N62AF ‘, .- COLLISION WITH 14TH STRFET BRIIDGE, -c ,+ . NEAR WASHINGTON NATIONAL AIRPO!iT .I . - WASHINGTON, I).C. JANUARY 13,1982 .---.--NTSB-AAR-82-8 --.__.._- _ ,c. I i e __- ’ ‘““‘Y’ED STATES GOVERNMENT I / f -4 . -~~sB-qjAR-82-8 1 PB82-910408 & . Ti t le and Subt i t le Aircraft -4ccident Report-- S.Report Date Air Florida, Inc., Boeing 737-222, N62AF, Collision August lo-, 1982 with 14th Street Bridge, Near Washington National 6.Performing Organization Airport, Washington, D.C., January 13. 1982. Code 7. Author(s) 8.Performing Organization Report No. I I I q. Performing Organization Name and Address 1 lO.Work Unit No. 3453-B I National Transportation Safety Board 11 .Contract or Grant No. Bureau of Accident Investigation H I Washington, D.C. 20594 / 13.Type of Report and 1 Period Covered 12.Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Aircraft Accident Report January 13, 1982 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, D. C. 20594 14.Sponsoring Agency Code . lY.Supplementary Notes 16.Abstract On January 13, 1982, Air Florida Flight 90, a Boeing 737-222 (N62AF), was a scheduled- flight to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, from Washington National Airport, Washington, D.C. There were 74 passengers, including 3 infants, and 5 crewmembers on board. The flight’s scheduled departure time was delayed about 1 hour 45 minutes due to a moderate to heavy snowfall which necessitated the temporary closing of the airport. Following takeoff from runway 36, which was made with snow and/or ice adhering to the aircraft, the aircraft at 1601 e.s.t. -

Appendix H: Comment Received on the Draft

Appendix H: Comments Received on the Draft EIS Appendix H includes the following: • Public Hearing Transcript • Comment Cards • Public Comments • Federal Agency Comments • State and Local Agency Comments • Organization Comments Appendix H1: Public Hearing Transcript Public Hearing October 22, 2019 Page 1 1 Public Hearing 2 Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) 3 Draft Section 4(f) Evaluation 4 and 5 Draft Section 106 Programmatic Agreement 6 7 8 9 Moderated by Anna Chamberlin 10 Tuesday, October 22, 2019 11 4:35 p.m. 12 13 14 Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs 15 1100 4th St., SW, Room E200 16 Washington, DC 20024 17 (202)442-4400 18 19 20 Reported by: Michael Farkas 21 JOB No.: 3532547 22 H-3 www.CapitalReportingCompany.com 202-857-3376 Public Hearing October 22, 2019 Page 2 1 C O N T E N T S 2 PAGE 3 Anna Chamberlin 3, 25 4 David Valenstein 8, 30 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 H-4 www.CapitalReportingCompany.com 202-857-3376 Public Hearing October 22, 2019 Page 3 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 MS. CHAMBERLAIN: Hello. If folks 3 can go ahead and get seated. We'll be starting 4 shortly with the presentation. Thank you. Good 5 afternoon, although it feels like evening with the 6 weather, but my name's Anna Chamberlain. I'm with the 7 District Department of Transportation, and we are the 8 project sponsor for the Long Bridge, EIS. -

10B-FY2020-Budget-Adoption-FINALIZED.Pdf

Report by Finance and Capital Committee (B) 03-28-2019 Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Board Action/Information Summary MEAD Number: Resolution: Action Information 202068 Yes No TITLE: Adopt FY2020 Operating Budget and FY2020-2025 CIP PRESENTATION SUMMARY: Staff will review feedback received from the public and equity analysis on the FY2020 Proposed Budget and request approval of the Public Outreach and Input Report, FY2020 Operating Budget and FY2020-2025 Capital Improvement Program (CIP). PURPOSE: The purpose of this item is to seek Board acceptance and approval of the Public Outreach and Input Report and Title VI equity analysis, and the FY2020 Operating Budget and FY2020-2025 CIP. DESCRIPTION: Budget Priorities: Keeping Metro Safe, Reliable and Affordable The budget is built upon the General Manager/CEO's Keeping Metro Safe, Reliable and Affordable (KMSRA) strategic plan. Metro is making major progress to achieve the goals of this plan by ramping up to average capital investment of $1.5 billion annually, establishing a dedicated capital trust fund exclusive to capital investment, and limiting jurisdictional annual capital funding growth to three percent. Metro continues to encourage the U.S. Congress to reauthorize the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act (PRIIA) beyond FY2020, which provides $150 million in annual federal funds matched by $150 million from the District of Columbia, State of Maryland, and Commonwealth of Virginia. In order to establish a sustainable operating model, Metro is limiting jurisdictional operating subsidy growth to three percent and deploying innovative competitive contracting. The items on the KMSRA agenda that remain to be completed include restructuring retirement benefits and creating a Rainy Day Fund. -

Gmf-Icsp-Wsw-2012

Agenda ICSP/GMF Meeting 9 am - 12pm October 9, 2011 Newseum, Knight Conference Center 555 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, 6th Street Entrance, The Freedom Forum Entrance, Washington, DC 20001 Co Chairs: Mary Saunders NIST, ICSP and Mary McKiel, EPA, GMF ICSP Closed Session – Federal Government Only 9:05-10:15 ICSP Closed Door Meeting – see ICSP meeting agenda for call in information ICSP/GMF Joint Session – Open to All Teleconference Call In: 1-866-469-3239 or 1-650-429-3300 Host access code (Scott): 25558273 Attendee access code: 25515125 10:30 Welcome- Co-Chairs: Mary Saunders NIST, ICSP and Mary McKiel, EPA, GMF 10:35 Remarks – Joe Bhatia, ANSI 10:40 Self introductions – All 10:45 Incorporation by Reference issues before PHMSA – Tim Klein, DOT 10:55 Discussion of Standards Incorporated by Reference Database – Fran Schrotter, ANSI 11:15 Discussion of NAESB ‘Green Button’ smart meter standard success story- Dave Wollman, NIST 11:35 ISO General Assembly Update – Mary McKiel, EPA 11:45 Current legislative activities of potential interest to the standardization community – Scott Cooper, ANSI 11:50-noon Other Business, Next Meeting Adjourn Directions to the Newseum Newseum 555 Pennsylvania Ave, NW 6th Street Entrance Washington, DC 20001 Metro Accessible Archives/Navy Memorial-Penn Quarter Station • • Take the Green or Yellow Line to the Archives/Navy Memorial-Penn Quarter Metro Station. Exit the station, turn left and walk toward Pennsylvania Avenue. Turn left onto Pennsylvania Avenue, walk toward the Capitol and cross Seventh Street. Walk one block to the Newseum, located at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and Sixth Street. -

Proposed Judiciary Square Historic District

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE HISTORIC PRESERVATION REVIEW BOARD APPLICATION FOR HISTORIC LANDMARK OR HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION New Designation _X_ Amendment of a previous designation __ Please summarize any amendment(s) Property name Judiciary Square Historic District If any part of the interior is being nominated, it must be specifically identified and described in the narrative statements. Address Roughly bounded by Constitution and Pennsylvania Avenues, N.W. and C Street, N.W. to the south, 6th Street to the west, G Street to the north, and 3rd and 4th Streets N.W to the east. See Boundary Description section for details. Square and lot number(s) Various Affected Advisory Neighborhood Commission 2C Date of construction 1791-1968 Date of major alteration(s) Various Architect(s) Pierre Charles L’Enfant, George Hadield, Montgomery C. Meigs, Elliott Woods, Nathan C. Wyeth, Gilbert S. Underwood, Louis Justement Architectural style(s) Various Original use Various Property owner Various Legal address of property owner Various NAME OF APPLICANT(S) DC Preservation League If the applicant is an organization, it must submit evidence that among its purposes is the promotion of historic preservation in the District of Columbia. A copy of its charter, articles of incorporation, or by-laws, setting forth such purpose, will satisfy this requirement. Address/Telephone of applicant(s) 1221 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20036 Name and title of authorized representative Rebecca Miller, Executive Director Signature of representative _______ _____ Date ____10/25/2018______ Name and telephone of author of application DC Preservation League, 202.783.5144 Office of Planning, 801 North Capitol Street, NE, Suite 3000, Washington, D.C. -

Reagan National

Monday, October 11th Honor Guard Teams / Motors / Support Staff Arrive Tuesday, October 12th Early Arrival Day (Reagan National Airport) for Survivors, 9 AM to 6 PM Colorado Survivor / Peace Officer Reception, 5 PM to 8 PM * * Wednesday, October 13th Official Arrival Day (Reagan National Airport) for Survivors, 9 AM to 6 PM C.O.P.S. 3rd Annual Blue Honor Gala, 6:30 PM Thursday, October 14th C.O.P.S. Blue Family Brunch at Hilton Alexandria Mark Center ***Colorado Peace Officer Group Photo 7th St NW & Indiana Ave NW, 5:15 PM*** NLEOMF Candlelight Vigil on the National Mall, 6 PM Friday, October 15th C.O.P.S. Survivors’ Conference & Kids Programs C.O.P.S. Picnic on the Patio Steve Young Honor Guard / Pipe Band Competition CANCELLED 27th Annual Emerald Society Memorial March, 5 PM Saturday, October 16th National Peace Officers’ Memorial Service (West Front Lawn US Capitol) 12 PM Stand Watch for the Fallen, 2 PM to Midnight at Memorial Sunday, October 17th 30th Anniversary Commemoration at Memorial, 9 AM to 10:30 AM Produced by Danny Veith - Colorado Fallen Hero Foundation - 720.373.6512 - [email protected] Page 1 of 18 Never before has this annual guide been distributed just 8-weeks before Police Week. This guide was delayed to insure Police Week events were not cancelled (as occurred in May of 2019), postponed (as occurred last May), all while monitoring District of Columbia health orders (for example, an order by the Mayor’s Office on July 29, 2021 to resume indoor mask use). Because of the pandemic, this is the first time National Police Week will occur outside the week encompassing May 15th. -

REFLECTIONS Washington’S Southeast / Southwest Waterfront

REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront CAMBRIA HOTEL Washington, DC Capitol Riverfront REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront Copyright © 2021 by Square 656 Owner, LLC Front cover image: Rendering of the Frederick Douglass Memorial ISBN: 978-0-578-82670-7 Bridge. The bridge connects the two shores of Designed by LaserCom Design, Berkeley CA the Anacostia River and is named after a former slave and human rights leader who became one of Washington’s most famous residents. District Department of Transportation vi FOREWORD REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront Marjorie Lightman, PhD William Zeisel, PhD CAMBRIA HOTEL Washington, DC Capitol Riverfront QED Associates LLC Washington, DC CAMBRIA HOTEL n REFLECTIONS vii Then ... A gardener’s residence on the site of the Cambria Hotel. The flat-roofed frame house, 18 feet wide and costing $1,800 to construct more than a century ago, was home to Samuel Howison, a market gardener. The cornice at the top of the building now graces the Cambria Hotel’s lobby, and a fireplace mantle accents the rooftop bar. Peter Sefton Now ... The Cambria Hotel at 69 Q Street SW, a part of the Southeast/Southwest waterfront’s renaissance. Donohoe Welcome to the Cambria Hotel Located in an historic part of one of the world’s great cities. ashington is a star-studded town where money and influence glitter on a world stage of W24/7 news bites. Images of the White House, the Capitol, and the Mall are recognized around the world as synonymous with majesty and power. Washington, the nation’s capital, shapes our times and history. -

National Gallery

West Building East Building Main Floor 1 – 13 13th- to 16th-Century Italian 35 – 35A, 15th- to 16th-Century 53 – 56 18th- and Early 19th-Century Tower 2 Modern and Paintings and Sculptures 38 – 41A Netherlandish and German French Paintings and Sculptures Contemporary Art Paintings and Sculptures 17 – 28 16th-Century Italian, French, and 57 – 59, 61 British Paintings and Sculptures Roof Special Exhibitions Terrace Spanish Paintings, Sculptures, 42 – 51 17th-Century Dutch and Flemish 60 – 60B, American Paintings and Sculptures Roof Terrace and Decorative Arts Paintings 62 – 71 Tower 3 Tower 2 Tower 1 Public Space 29 – 34, 17th- to 18th-Century Italian, 52 18th- and 19th-Century Spanish 80 – 93 19th-Century French Paintings 36 – 37 Spanish, and French Paintings and French Paintings Closed to the Public 72 – 79 Special Exhibitions Roof Terrace Tower 3 Tower 1 Tower Level 19 18 17 20 21 24 12 23 13 25 22 Sculpture Garden 26 27 11 28 10 19 9 18 6 Tower 2 17 5 3 Lobby A 20 8 2 31 24 West 21 7 23 Garden 12 4 29 13 80 32 25 Court22 Lobby B 1 79 30 11 91 Sculpture Garden 26 27 10 81 78 33 28 45 9 92 90 87 82 37 46 6 88 86 75 Tower 2 38 5 93 76 43 48 3 83 77 34 Lobby A 44 8 51 50C 2 89 31 36 West 47 7 85 74 Tower 1 39 Garden 49 4 Rotunda 84 73 Tower 3 35 29 42 50B 80 32 35A Court Lobby B 50 1 79 30 40 50A 91 78 41 52 92 90 87 Lobby C East81 82 33 41A 45 Information Founders 56 75 72 37 46 Room 88 86 Garden 76 38 48 Room 53 93 57 77 34 43 89 58 83Court Lobby D Terrace Café 36 44 47 51 50C 54 74 Tower 1 39 55 85 73 Tower 3 Upper Level 35 42 49 50B -

History of US Park Police

National Park Service: History of U.S. Park Police THE UNITED STATES Home PARK POLICE Origins A HISTORY Early Personalities and by Barry Mackintosh Problems History Division Upgrading the Force National Park Service Defending the Force Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. The Force in Turmoil 1989 The Force Matures Appendix The United States Park Police is a unique organization within the National Park Service. It is the oldest NPS component, predating its Links adoptive parent by half a century (or more, some would argue). Its personnel wear distinctive uniforms, perform specialized functions, and are regularly assigned to a small minority of national parklands. Most NPS employees are probably unfamiliar with the Park Police and may well wonder why the organization exists. From the demanding nature of their duties and the evident public service they perform, Park Police personnel surely know why the organization exists; but few of them may know how it began and how far it has come to reach its present elite status. This short history is intended to acquaint NPS employees in general and Park Police personnel in particular with its background and evolution. If it helps them and others interested in the force to better understand and appreciate this special NPS unit, it will have served its purpose. History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact Top Last Modified: Fri, Dec 10 1999 07:08:48 am PDT http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/nmpidea.htm http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/police/index.htm[1/14/2014 5:22:08 PM] U.S. -

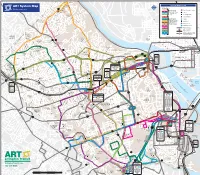

ART System Map (PDF, 741KB)

N G lebe Rd Madison 53B 53A Community System Map Legend ART System Map Center Military Rd d R Fort ART Bus Routes Ch e Ethan es 120 b te le Allen Effective August 2019 r G 23AT br ld 41 oo N O Fort More Frequent Capital Bikeshare Location k Rd Ethan Allen 43 Walker Chapel Trench (Thick lines: 20 min. Library and Cemetery 45 or less frequency Roberts Ln 55 Gulf Branch all day) Community Center N Albemarle St 38th St N Nature Center 42 Point of Interest N Glebe Rd 3 5 th 51 S Less Frequent t Hospital N N Pollard St 52 Jamestown 37th St N (Thin lines: 20 min. Elementary Dittmar Rd 53 or more frequency High School School 61 36th St N during portion of Middle School 62 the day or all day) 53 72 Elementary School 72 t 74 S 23AT Old Dominion Dr w 00 Metrobus Routes N o t 75 r S d t s o Williamsburg Blvd 1 77 o 3 Metrorail Station N Glebe Rd W 15K N 84 Metrorail Line Military Rd Little Falls Rd 87 Virginia Rail Express (VRE) 87X Station and Rail Line Williamsburg Middle FAIRFAX School lvd ¥¬!RLINGTON¬#OUNTY¬#OMMUTER¬3ERVICES ¬6IRGINIA¬¬s¬¬$ESIGN¬BY¬3MARTMAPS ¬+NOXVILLE ¬4. rg B Rock Spring Rd Discovery bu Taylor COUNTY ms Elementary illia Elementary METRORAIL RED LINE School W School G Georgetown eo 309 120 rg University 26th St N e N Harrison St John W 25th Rd N as 53 Saegmuller N hin St N Stuart St g House 30th Marymount ton 38B 26th Rd N M N Kensington St University e FAIRFAX COUNTY m John Marshall Dr or ial Pkw ARLINGTON COUNTY Yorktown Blvd 25th St N Nelly Custis Dr y Farragut d lv 26th St N town B North Station 52 York N Taylor St Woodmont 38B KEY BRIDGE Yorktown N Center 3Y 3Y 38B N Powhatan St d R High School G 38B e lls N 11Y 38B Little Fa o 23AT Fort 38B NE LI r 309 VER V IL Yorktown 28th St N g 62 Lorcom Ln C.F.