History of US Park Police

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider There are so many things to do when visiting D.C., many for free, and here are a few you may have not done before. They may make it worthwhile to come to D.C. early or to stay to the end of the weekend. Getting to the Sites: • D.C. Sites and the Pentagon: Metro is a way around town. The hotel is four minutes from the Metro’s Mt. Vernon Square/7th St.-Convention Center Station. Using Metro or walking, or a combination of the two (or a taxi cab) most D.C. sites and the Pentagon are within 30 minutes or less from the hotel.1 Googlemaps can help you find the relevant Metro line to use. Circulator buses, running every 10 minutes, are an inexpensive way to travel to and around popular destinations. Routes include: the Georgetown-Union Station route (with a stop at 9th and New York Avenue, NW, a block from the hotel); and the National Mall route starting at nearby Union Station. • The Mall in particular. Many sites are on or near the Mall, a five-minute cab ride or 17-minute walk from the hotel going straight down 9th Street. See map of Mall. However, the Mall is huge: the Mall museums discussed start at 3d Street and end at 14th Street, and from 3d Street to 14th Street is an 18-minute walk; and the monuments on the Mall are located beyond 14th Street, ending at the Lincoln Memorial at 23d Street. -

East-Download The

TIDAL BASIN TO MONUMENTS AND MUSEUMS Outlet Bridge TO FRANKLIN L’ENFANT DELANO THOMAS ROOSEVELT ! MEMORIAL JEFFERSON e ! ! George ! # # 14th STREET !!!!! Mason Park #! # Memorial MEMORIAL # W !# 7th STREET ! ! # Headquarters a ! te # ! r ## !# !# S # 395 ! t # !! re ^ !! e G STREET ! OHIO DRIVE t t ! ! # e I Street ! ! ! e ! ##! tr # ! !!! S # th !!# # 7 !!!!!! !! K Street Cuban ! Inlet# ! Friendship !!! CASE BRIDGE## SOUTHWEST Urn ! # M Bridge ! # a # ! # in !! ! W e A !! v ! e ! ! ! n ! ! u East Potomac !!! A e 395 ! !! !!!!! ^ ! Maintenance Yard !! !!! ! !! ! !! !!!! S WATERFRONT ! e ! !! v ! H 6 ri ! t ! D !# h e ! ! S ! y # I MAINE AVENUE Tourmobile e t George Mason k ! r ! c ! ! N e !! u ! e ! B East Potomac ! Memorial !!! !!! !! t !!!!! G Tennis Center WASHINGTON! !! CHANNEL I STREET ##!! !!!!! T !"!!!!!!! !# !!!! !! !"! !!!!!! O Area!! A Area B !!! ! !! !!!!!! N ! !! U.S. Park ! M S !! !! National Capital !!!!!#!!!! ! Police Region !!!! !!! O !! ! Headquarters Headquarters hi !! C !!!! o !!! ! D !!!!! !! Area C riv !!!!!!! !!!! e !!!!!! H !! !!!!! !!O !! !! !h ! A !! !!i ! ! !! !o! !!! Maine !!!D ! ! !!r !!!! # Lobsterman !!iv ! e !! N !!!!! !! Memorial ! ! !!" ! WATER STREET W !!! !! # ! ! N a ! ! ! t !! ! !! e !! ##! r !!!! #! !!! !! S ! ! !!!!!!! ! t !!! !! ! ! E r !!! ! !!! ! ! e !!!! ! !!!!!! !!! e ! #!! !! ! ! !!! t !!!!!#!! !!!!! BUCKEYE DRIVE Pool !! L OHIO #!DRIVE! !!!!! !!! #! !!! ! Lockers !!!## !! !!!!!!! !! !# !!!! ! ! ! ! !!!!! !!!! !! !!!! 395 !!! #!! East Potomac ! ! !! !!!!!!!!!!!! ! National Capital !!!! ! ! -

NTSB Accident Report

TRANSPORTATION SAFETII! BOARD AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT l$EPOfiT,, . !!;, , I,_ .: I ‘/ AlR FLORIIDA, INC. -: BOEING 737-222, N62AF ‘, .- COLLISION WITH 14TH STRFET BRIIDGE, -c ,+ . NEAR WASHINGTON NATIONAL AIRPO!iT .I . - WASHINGTON, I).C. JANUARY 13,1982 .---.--NTSB-AAR-82-8 --.__.._- _ ,c. I i e __- ’ ‘““‘Y’ED STATES GOVERNMENT I / f -4 . -~~sB-qjAR-82-8 1 PB82-910408 & . Ti t le and Subt i t le Aircraft -4ccident Report-- S.Report Date Air Florida, Inc., Boeing 737-222, N62AF, Collision August lo-, 1982 with 14th Street Bridge, Near Washington National 6.Performing Organization Airport, Washington, D.C., January 13. 1982. Code 7. Author(s) 8.Performing Organization Report No. I I I q. Performing Organization Name and Address 1 lO.Work Unit No. 3453-B I National Transportation Safety Board 11 .Contract or Grant No. Bureau of Accident Investigation H I Washington, D.C. 20594 / 13.Type of Report and 1 Period Covered 12.Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Aircraft Accident Report January 13, 1982 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, D. C. 20594 14.Sponsoring Agency Code . lY.Supplementary Notes 16.Abstract On January 13, 1982, Air Florida Flight 90, a Boeing 737-222 (N62AF), was a scheduled- flight to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, from Washington National Airport, Washington, D.C. There were 74 passengers, including 3 infants, and 5 crewmembers on board. The flight’s scheduled departure time was delayed about 1 hour 45 minutes due to a moderate to heavy snowfall which necessitated the temporary closing of the airport. Following takeoff from runway 36, which was made with snow and/or ice adhering to the aircraft, the aircraft at 1601 e.s.t. -

Appendix H: Comment Received on the Draft

Appendix H: Comments Received on the Draft EIS Appendix H includes the following: • Public Hearing Transcript • Comment Cards • Public Comments • Federal Agency Comments • State and Local Agency Comments • Organization Comments Appendix H1: Public Hearing Transcript Public Hearing October 22, 2019 Page 1 1 Public Hearing 2 Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) 3 Draft Section 4(f) Evaluation 4 and 5 Draft Section 106 Programmatic Agreement 6 7 8 9 Moderated by Anna Chamberlin 10 Tuesday, October 22, 2019 11 4:35 p.m. 12 13 14 Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs 15 1100 4th St., SW, Room E200 16 Washington, DC 20024 17 (202)442-4400 18 19 20 Reported by: Michael Farkas 21 JOB No.: 3532547 22 H-3 www.CapitalReportingCompany.com 202-857-3376 Public Hearing October 22, 2019 Page 2 1 C O N T E N T S 2 PAGE 3 Anna Chamberlin 3, 25 4 David Valenstein 8, 30 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 H-4 www.CapitalReportingCompany.com 202-857-3376 Public Hearing October 22, 2019 Page 3 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 MS. CHAMBERLAIN: Hello. If folks 3 can go ahead and get seated. We'll be starting 4 shortly with the presentation. Thank you. Good 5 afternoon, although it feels like evening with the 6 weather, but my name's Anna Chamberlain. I'm with the 7 District Department of Transportation, and we are the 8 project sponsor for the Long Bridge, EIS. -

REFLECTIONS Washington’S Southeast / Southwest Waterfront

REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront CAMBRIA HOTEL Washington, DC Capitol Riverfront REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront Copyright © 2021 by Square 656 Owner, LLC Front cover image: Rendering of the Frederick Douglass Memorial ISBN: 978-0-578-82670-7 Bridge. The bridge connects the two shores of Designed by LaserCom Design, Berkeley CA the Anacostia River and is named after a former slave and human rights leader who became one of Washington’s most famous residents. District Department of Transportation vi FOREWORD REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront Marjorie Lightman, PhD William Zeisel, PhD CAMBRIA HOTEL Washington, DC Capitol Riverfront QED Associates LLC Washington, DC CAMBRIA HOTEL n REFLECTIONS vii Then ... A gardener’s residence on the site of the Cambria Hotel. The flat-roofed frame house, 18 feet wide and costing $1,800 to construct more than a century ago, was home to Samuel Howison, a market gardener. The cornice at the top of the building now graces the Cambria Hotel’s lobby, and a fireplace mantle accents the rooftop bar. Peter Sefton Now ... The Cambria Hotel at 69 Q Street SW, a part of the Southeast/Southwest waterfront’s renaissance. Donohoe Welcome to the Cambria Hotel Located in an historic part of one of the world’s great cities. ashington is a star-studded town where money and influence glitter on a world stage of W24/7 news bites. Images of the White House, the Capitol, and the Mall are recognized around the world as synonymous with majesty and power. Washington, the nation’s capital, shapes our times and history. -

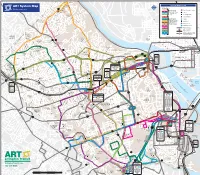

ART System Map (PDF, 741KB)

N G lebe Rd Madison 53B 53A Community System Map Legend ART System Map Center Military Rd d R Fort ART Bus Routes Ch e Ethan es 120 b te le Allen Effective August 2019 r G 23AT br ld 41 oo N O Fort More Frequent Capital Bikeshare Location k Rd Ethan Allen 43 Walker Chapel Trench (Thick lines: 20 min. Library and Cemetery 45 or less frequency Roberts Ln 55 Gulf Branch all day) Community Center N Albemarle St 38th St N Nature Center 42 Point of Interest N Glebe Rd 3 5 th 51 S Less Frequent t Hospital N N Pollard St 52 Jamestown 37th St N (Thin lines: 20 min. Elementary Dittmar Rd 53 or more frequency High School School 61 36th St N during portion of Middle School 62 the day or all day) 53 72 Elementary School 72 t 74 S 23AT Old Dominion Dr w 00 Metrobus Routes N o t 75 r S d t s o Williamsburg Blvd 1 77 o 3 Metrorail Station N Glebe Rd W 15K N 84 Metrorail Line Military Rd Little Falls Rd 87 Virginia Rail Express (VRE) 87X Station and Rail Line Williamsburg Middle FAIRFAX School lvd ¥¬!RLINGTON¬#OUNTY¬#OMMUTER¬3ERVICES ¬6IRGINIA¬¬s¬¬$ESIGN¬BY¬3MARTMAPS ¬+NOXVILLE ¬4. rg B Rock Spring Rd Discovery bu Taylor COUNTY ms Elementary illia Elementary METRORAIL RED LINE School W School G Georgetown eo 309 120 rg University 26th St N e N Harrison St John W 25th Rd N as 53 Saegmuller N hin St N Stuart St g House 30th Marymount ton 38B 26th Rd N M N Kensington St University e FAIRFAX COUNTY m John Marshall Dr or ial Pkw ARLINGTON COUNTY Yorktown Blvd 25th St N Nelly Custis Dr y Farragut d lv 26th St N town B North Station 52 York N Taylor St Woodmont 38B KEY BRIDGE Yorktown N Center 3Y 3Y 38B N Powhatan St d R High School G 38B e lls N 11Y 38B Little Fa o 23AT Fort 38B NE LI r 309 VER V IL Yorktown 28th St N g 62 Lorcom Ln C.F. -

The D.C. Freeway Revolt and the Coming of Metro Part 6 a New Administration Takes Over

The D.C. Freeway Revolt and the Coming of Metro Part 6 A New Administration Takes Over Table of Contents The New Administration Gets to Work .......................................................................................... 2 Transition in the District ................................................................................................................. 7 Waiting for Secretary Volpe ......................................................................................................... 10 Secretary Volpe Gets Involved ..................................................................................................... 15 Trying to Break the Logjam .......................................................................................................... 21 Backstage Negotiation .................................................................................................................. 24 The Nixon Administration Gets Involved ..................................................................................... 36 Advancing Metro .......................................................................................................................... 42 How To Break An Impasse ........................................................................................................... 48 Regrouping After a Loss ............................................................................................................... 65 Imminent Compromise ................................................................................................................ -

Appendix F: Agency, Operator, and Organization Comments Received

LONG BRIDGE PROJECT 111Connecting North ond South Through our Notion'sCopitol Appendix F: Agency, Operator, and Organization Comments Received Federal Agency Comments United States Environmental Protection Agency ........................................................................ F-1 United States Department of the Interior ................................................................................... F-5 Federal Aviation Administration ........................................................................................... F-10 National Capital Planning Commission .................................................................................. F-11 National Marine Fisheries Service ......................................................................................... F-14 State, Local, and Regional Agency Comments District Councilmember Silverman ........................................................................................ F-18 District Department of Energy and Environment ................................................................... F-19 DC Water ............................................................................................................................. F-21 Northern Virginia Transportation Commission ...................................................................... F-25 Potomac and Rappahannock Transportation Commission ..................................................... F-27 Virginia Railway Express ...................................................................................................... -

Long Bridge Study

District Department of Transportation LONG BRIDGE STUDY January 2015 Cover photo credits: Zefiro 280 High Speed Rail Train courtesy of Bombadier. LONG BRIDGE STUDY FINAL REPORT Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS & ACRONYMS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Introduction 1 History 3 Bridge Structure 3 Purpose and Need 4 Bridge Condition and Current Operations 5 Alternatives 6 Railroad Alternatives 10 Alternative 1: No Build 10 Alternative 2: Two-Track Bridge 10 Alternative 3: Four-Track Bridge 11 Alternative 4: Four-Track Tunnel 11 Railroad and Other Modal Alternatives 11 Alternative 5: Four-Track Bridge and Pedestrian/Bicycle 11 Alternative 6: Four-Track Bridge with Pedestrian/Bicycle and Streetcar 12 Alternative 7: Four-Track Bridge with Pedestrian/Bicycle and Shared Streetcar/ General-Purpose Lanes 12 Alternative 8: Four-Track Bridge with Pedestrian/Bicycle, Shared Streetcar/General- Purpose Lanes and Additional General-Purpose Lanes 13 Transportation Analysis 14 Freight and Passenger Rail 14 Freight and Passenger Outlook 16 Analysis of Pedestrians and Bicycles 16 Analysis of Transit and Vehicular Modes 17 Engineering, Constructability and Costing 18 4-Track Concepts - Alternatives 2-4 20 Environmental Review and Resource Identification 21 4-Track Concepts - Alternatives 5-8 21 Findings 22 Project Coordination 24 Acknowledgements 25 CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW 1 Background 1 The Long Bridge 1 Study Area 2 Freight, Passenger, and Commuter Rail 4 Long Bridge History 5 Relationship to Other Studies 7 Southeast High-Speed Rail Market and Demand Study, August -

Can't See the Map?

Glenmont Metrorail System Wheaton Station West Falls Church Metro Station East Falls Church Metro Station MARYLAND Route 15KL Shady Grove RED LINE Forest Glen Transfer station Tysons Corner Interstate 66 west Note about street names on this map Rockville FC 425, Vienna Silver Spring Metro parking FC 553, FC 950 427 Twinbrook FC 951 F Washington Blvd. All streets north of Arlington Blvd. (Route 50) George Mason Greenbelt 585 G White Flint 495 952 H University Takoma 980 are designated “North” as in “North Quincy Grosvenor-Strathmore College Park-U of Md I FC 505, Medical Center Wolftrap RED LINE Prince Georges Plaza 555 Escalators to 15L Loudoun Shuttle Dulles St.” or “16th St. North”. All streets south of Bethesda GREEN/YELLOWWest LINE Hyattsville E Flyer Metrorail trains S C D yc WASHINGTON, D.C. 95 Transit A B Arlington Blvd. are likewise designated “South”. FORT TOTTEN amore St. 15K Friendship Heights Georgia Ave-Petworth -495 Tenleytown-AU FC 551, 552, station platform 0 50 100 parking Chain Bridge Columbia Heights Brookland-CUA 554, 557 Van Ness-UDC Metrorail Blue, Orange, Yellow Lines Cleveland Park U Street pedestrian Feet FUTURE SILVER LINE Rhode Island Ave bridge CHAIN BRIDGE George Washington Mem’l. Pkwy. Woodley Park Dupont Circle Metrorail stations Interstate 66 east FOREST Farragut West Farragut North Shaw-Howard U New Carrollton Foggy Bottom-GWU Metrobus 24T,Tysons Corner Mt Vernon Sq ART 52 New York Ave LINE Landover ART bus routes ART 52, 53 McPherson Union Station Cheverly Columbia Heights ART 53B Sq NORTH Judiciary Sq ANGE B STAFFORD ORANGE LINE ROSSLYN Woodley Park-ZDoo/eanAwdamsood Morgan 23A ART 53A Vienna METRO CENTER GALLERY PLACE OR Metrobus routes A Madison Minnesota Ave Largo 28AX Federal Triangle Archives D ALBEMARLE Community RIVERCREST BLUE/ORANGE LINE Town Center Military Rd. -

Virginia Railway Express

VIRGINIA RAILWAY EXPRESS IEEE Vehicular Technology Society National Capital Chapter September 11, 2018 VIRGINIA RAILWAY EXPRESS 1 1 TODAY’S REMARKS . Introduction . VRE Overview . VRE Capital Program − Program Overview − Long Bridge “The 12-Mile Bridge” − Midday Storage − L’Enfant Improvements − Crystal City Improvements − Other Fredericksburg Line Improvements − Other Manassas Line Improvements . Questions − Perhaps answers... VIRGINIA RAILWAY EXPRESS 2 WHO WE ARE A commuter rail system Running on existing railroad tracks Serving Washington DC and Northern Virginia Carrying long-distance commuters to DC, Arlington & Alexandria Two lines, 96 miles Adding peak capacity to I-95, I-395 & I-66 corridors* 19,000 weekday trips Commuters that would otherwise drive alone in cars* VIRGINIAVIRGINIA RAILWAY RAILWAY EXPRESS EXPRESS * Source: Texas Transportation Institute, Virginia Railway Express Congestion Relief Contribution; 2014 3 WHO WE ARE VRE is a “joint project” of two Transportation Commissions Northern Virginia Potomac & Rappahannock Transportation Commission Transportation Commission VRE Master Agreement Northern Jurisdictions: Southern Jurisdictions: Two VA Counties Three VA Counties One VA City Three VA Cities VRE VRE Operations Operations Board Board VRE Staff VIRGINIA RAILWAY EXPRESS 4 WHERE WE OPERATE . VRE operates on tracks owned and controlled by its three “host railroads”: ‒ CSX Transportation (CSXT) ‒ Norfolk Southern (NS) ‒ National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) VIRGINIA RAILWAY EXPRESS 5 WHAT WE ARE KNOWN FOR Safe -

National-Mall-Map.Pdf

To National To National To Gandhi, Shevchenko, To African American To Carter G. Woodson Home WISCONSIN AVE NW O ST NW Zoological Park Creek O ST NW Zoological Park and Masaryk statues Mary McLeod Bethune Civil War Memorial O ST NW National Historic Site O ST NW Council House (temporarily closed) k National Park Service Visitor Services c National Historic Site o R Information Restrooms Parking O ST NW SCOTT CIRCLE Refreshment Ice skating rink Water taxi 35TH ST NW ST 35TH John Witherspoon Webster Georgetown N ST NW Memorial Samuel Hahnemann Memorial N ST NW stand University Scott Souvenir shop Capital Bikeshare 28TH ST NW ST 28TH Tennis court 33RD ST NW ST 33RD and Hospital NW ST 34TH 37TH ST NW ST 37TH N ST NW N ST NW ROCK Circulator stop VERMONT AVE NW Bookstore Golf course CONNECTICUT AVE NW 1 Georgetown CREEK Tickets Statue, monument, THOMAS OLIVE ST NW RHODE ISLAND AVE NW or point of interest PROSPECT ST NW PARK Longfellow CIRCLE MOUNT VERNON Nuns of the Battlefield SQUARE–7th STREET– Old Stone House M ST NW M ST NW CONVENTION CENTER M ST NW Metrorail System National Geographic Thomas M ST NW National 9TH ST NW 12TH ST NW Georgetown Visitor Center Museum Geographic 10TH ST NW M ST NW Chesapeake and Ohio Canal 29 Station name Metro lines Society NEW JERSEY AVE NW National Historical Park West Washington METRO Red line Green line CHESAPEAKE AND Francis Scott Key Convention NEW YORK AVE NW CENTER Memorial MASSACHUSETTS AVE NW Center Orange line Yellow line OHIO CANAL Chesapeake and Ohio Canal PENNSYLVANIA AVE NW End 50 Douglas Mount Entrance/exit NATIONAL L ST NW Blue line Silver line Burke Gompers to Metro station NoMa W 17TH ST NW 16TH ST NW 15TH ST NW 14TH ST NW HISTORICAL PARK A 23RD ST NW Vernon TE 7TH ST NW R ST L ST NW L ST NW L ST NW 395 NW Square Downtown Washington addresses indicate quadrants—NW,Greyhound NE, SE, and SW— 29 FARRAGUT 13TH ST NW starting at the U.S.