Good Afternoon and Welcome to the John F. Kennedy Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

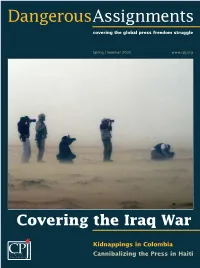

DA Spring 03

DangerousAssignments covering the global press freedom struggle Spring | Summer 2003 www.cpj.org Covering the Iraq War Kidnappings in Colombia Committee to·Protect Cannibalizing the Press in Haiti Journalists CONTENTS Dangerous Assignments Spring|Summer 2003 Committee to Protect Journalists FROM THE EDITOR By Susan Ellingwood Executive Director: Ann Cooper History in the making. 2 Deputy Director: Joel Simon IN FOCUS By Amanda Watson-Boles Dangerous Assignments Cameraman Nazih Darwazeh was busy filming in the West Bank. Editor: Susan Ellingwood Minutes later, he was dead. What happened? . 3 Deputy Editor: Amanda Watson-Boles Designer: Virginia Anstett AS IT HAPPENED By Amanda Watson-Boles Printer: Photo Arts Limited A prescient Chinese free-lancer disappears • Bolivian journalists are Committee to Protect Journalists attacked during riots • CPJ appeals to Rumsfeld • Serbia hamstrings Board of Directors the media after a national tragedy. 4 Honorary Co-Chairmen: CPJ REMEMBERS Walter Cronkite Our fallen colleagues in Iraq. 6 Terry Anderson Chairman: David Laventhol COVERING THE IRAQ WAR 8 Franz Allina, Peter Arnett, Tom Why I’m Still Alive By Rob Collier Brokaw, Geraldine Fabrikant, Josh A San Francisco Chronicle reporter recounts his days and nights Friedman, Anne Garrels, James C. covering the war in Baghdad. Goodale, Cheryl Gould, Karen Elliott House, Charlayne Hunter- Was I Manipulated? By Alex Quade Gault, Alberto Ibargüen, Gwen Ifill, Walter Isaacson, Steven L. Isenberg, An embedded CNN reporter reveals who pulled the strings behind Jane Kramer, Anthony Lewis, her camera. David Marash, Kati Marton, Michael Massing, Victor Navasky, Frank del Why I Wasn’t Embedded By Mike Kirsch Olmo, Burl Osborne, Charles A CBS correspondent explains why he chose to go it alone. -

The Kosovo Report

THE KOSOVO REPORT CONFLICT v INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE v LESSONS LEARNED v THE INDEPENDENT INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON KOSOVO 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford Executive Summary • 1 It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, Address by former President Nelson Mandela • 14 and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Map of Kosovo • 18 Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Introduction • 19 Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw PART I: WHAT HAPPENED? with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Preface • 29 Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the uk and in certain other countries 1. The Origins of the Kosovo Crisis • 33 Published in the United States 2. Internal Armed Conflict: February 1998–March 1999 •67 by Oxford University Press Inc., New York 3. International War Supervenes: March 1999–June 1999 • 85 © Oxford University Press 2000 4. Kosovo under United Nations Rule • 99 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) PART II: ANALYSIS First published 2000 5. The Diplomatic Dimension • 131 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, 6. International Law and Humanitarian Intervention • 163 without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, 7. Humanitarian Organizations and the Role of Media • 201 or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

AGENDA June 3 – 4, 2017

Pulitzer Center Pulitzer Center Gender Lens Conference Gender Lens Conference June 3 – 4, 2017 AGENDA June 3 – 4, 2017 Saturday, June 3, 2017 2:00-2:30 Registration 2:30-3:45 Concurrent panels 1) Women in Conflict Zones Welcome: Tom Hundley, Pulitzer Center Senior Editor • Susan Glasser, Politico chief international affairs columnist and host of The Global Politico (moderator) • Paula Bronstein, freelance photojournalist (G) • Sarah Holewinski, senior fellow, Center for a New American Security, board member, Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) • Sarah Topol, freelance journalist (G) • Cassandra Vinograd, freelance journalist (G) 2) Property Rights Welcome: Steve Sapienza, Pulitzer Center Senior Producer • LaShawn Jefferson, deputy director, Perry World House, University of Pennsylvania (moderator) • Amy Toensing, freelance photojournalist (G) • Paola Totaro, editor, Thomson Reuters Foundation’s Place • Nana Ama Yirrah, founder, COLENDEF 3) Global Health • Rebecca Kaplan, Mellon/ACLS Public Fellow at the Pulitzer Center (moderator) • Jennifer Beard, Clinical Associate Professor, Boston University School of Public Health (Pulitzer Center Campus Consortium partner) • Caroline Kouassiaman, senior program officer, Sexual Health and Rights, American Jewish World Service (AJWS) • Allison Shelley, freelance photojournalist (G) • Rob Tinworth, filmmaker (G) 4:00-4:30 Coffee break 4:30-5:45 Concurrent panels 1) Diversifying the Story • Yochi Dreazen, foreign editor of Vox.com (moderator) (G) • Kwame Dawes, poet, writer, actor, musician, professor -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1998 - June 30,1999 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-•1789 TTele . (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www.cfr.org E-mail communications@cfr. org Officers and Directors, 1999–2000 Officers Directors Term Expiring 2004 Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 2000 John Deutch Chairman of the Board Jessica P.Einhorn Carla A. Hills Maurice R. Greenberg Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Robert D. Hormats* Vice Chairman Maurice R. Greenberg William J. McDonough* Leslie H. Gelb Theodore C. Sorensen President George J. Mitchell George Soros* Michael P.Peters Warren B. Rudman Senior Vice President, Chief Operating Term Expiring 2001 Leslie H. Gelb Officer, and National Director ex officio Lee Cullum Paula J. Dobriansky Vice President, Washington Program Mario L. Baeza Honorary Officers David Kellogg Thomas R. Donahue and Directors Emeriti Vice President, Corporate Affairs, Richard C. Holbrooke Douglas Dillon and Publisher Peter G. Peterson† Caryl P.Haskins Lawrence J. Korb Robert B. Zoellick Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Vice President, Studies David Rockefeller Term Expiring 2002 Elise Carlson Lewis Honorary Chairman Vice President, Membership Paul A. Allaire and Fellowship Affairs Robert A. Scalapino Roone Arledge Abraham F. Lowenthal Cyrus R.Vance John E. Bryson Vice President Glenn E. Watts Kenneth W. Dam Anne R. Luzzatto Vice President, Meetings Frank Savage Janice L. Murray Laura D’Andrea Tyson Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2003 Judith Gustafson Secretary Peggy Dulany Martin S. -

Iraqi Combatant and Noncombatant Fatalities in the 1991 Gulf War

The Wages of War: Iraqi Combatant and Noncombatant Fatalities in the 2003 Conflict Project on Defense Alternatives Research Monograph #8 Carl Conetta, 20 October 2003 Appendix 2: Iraqi Combatant and Noncombatant Fatalities in the 1991 Gulf War INDEX 1. Iraqi civilian fatalities in the 1991 Gulf War 2. Iraqi military personnel killed during the air war 3. Iraqi military personnel killed during the ground war 4. Buried alive: 1st Division breeching operations 5. The “Highway(s) of Death” Sources We accept 3,664 (rounded to 3,500+) as an estimate of the number of Iraqi civilians killed in the 1991 Gulf War. Regarding military personnel, we estimate that between 20,000 and 26,000 were killed in the conflict. 1. Iraqi civilian fatalities in the 1991 Gulf War The estimate for civilian deaths is based on a study conducted by Beth Osborne Daponte, a former Census Bureau analyst and currently a senior research scientist at Carnegie Mellon University (Daponte 1993). With regard to civilian casualties directly attributable to the war, the study builds on earlier research conducted by Humans Rights Watch shortly after the war (HRW 1991). The HRW estimate of 2,500 to 3,000 Iraqi civilians killed in the war was based on eyewitness reports, although no claim was made that the survey was comprehensive. From this source Daponte compiled a database of 2,665 deaths, after removing duplicate reports. Subsequently, she checked this on a province by province basis against the official Iraqi records of 2,278 civilian deaths from the war. Overall it appeared that the Iraqi government had undercounted the civilian death toll, although this was not systematic. -

Women War Reporters' Resistance and Silence In

WOMEN WAR REPORTERS’ RESISTANCE AND SILENCE IN THE FACE OF SEXISM AND SEXUAL VIOLENCE LINDA STEINER UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND. PHILIP MERRILL COLLEGE OF JOURNALISM. COLLEGE PARK, MARYLAND 20742, EUA [email protected] RESUMO As mulheres começaram a fazer reportagens de guerra em meados do século XIX, cobrindo, entre outras guerras, as revoluções europeias e a Guerra Civil dos EUA. Com a Primeira e Segunda Guerras Mundiais e especialmente com a Guer- ra do Vietname, o número de mulheres repórteres de guerra aumentou ao longo do século XX. O seu número voltou mais recentemente a aumentar, quando muitas organizações noticiosas precisavam de jornalistas no Iraque, no Afeganistão e no Paquistão. No entanto, as reportagens de guerra permanecem amplamente consi- deradas como um campo dos homens. Continua a ser um campo altamente sexista. As jornalistas de guerra continuam a enfrentar condescendência, pseudo-protecio- nismo, desdém, comportamentos obscenos e hostilidade por parte dos seus patrões, rivais, militares e do público. São também sujeitas a violência sexual, embora sejam desencorajadas de queixar-se desses assaltos, para que possam continuar a traba- lhar. Esta investigação centra-se no sexismo e assédio sexual enfrentados por mu- lheres repórteres de guerra contemporâneas, com especial atenção a Lara Logan, cuja carreira demonstra muitas dessas altas tensões de género. PALAVRAS-chAVE Mulheres repórteres de guerra; sexismo; culpadas enquanto vítimas; violên- cia sexual ABSTRACT Women began reporting on war in the mid-nineteenth century, covering, among other wars, Europeans revolutions and the US Civil War. The numbers of women report- ing on war increased over the twentieth century with the First and Second World Wars and especially the Vietnam War. -

The Dictator's Army Précis Interviews Chappell Lawson on IPL CIS In

FALL 2015 précis Interviews Chappell Lawson on IPL IN THIS ISSUE arlier this year, CIS established the MIT précis Interview: Chappell Lawson 2 EInternational Policy Lab, whose mission is The Dictator’s Army 6 “to enhance the impact of MIT research on public Caitlin Talmadge policy.” Professor Chappell Lawson, who serves as CIS in American War Gaming 8 the faculty lead, sat down with précis to discuss the Reid Pauly program. Neuffer Fellow Meera Srinivasan 11 The International Policy Lab is awarding up to Events 12 $10,000 to faculty and research staff with principal investigator status who wish to convey their research End Notes 14 to policymakers. continued on page 2 OF NOTE The Dictator’s Army Global Refugee Crisis by Caitlin Talmadge The millions of Syrian refugees displaced by their country’s four-year civil war hy do some states successfully convert their constitute a major tragedy...a group of Wnational assets into operational- and tacti- scholars and relief workers said at an cal- level fighting power in war, whereas others fail MIT Starr Forum. even when they have the economic, demographic, continued on page 4 and technological endowments needed to succeed? New Wilhelm Fellow continued on page 6 Paul Heer, a recent National Intelli- gence Officer for East Asia, has been named a Robert E. Wilhelm fellow. CIS in American War Gaming Heer arrived to MIT in September 2015 and will be in residence at CIS by Reid Pauly for the 2015-2016 academic year. continued on page 11 here did this methodology of modern war Wgames originate? In large part at MIT, where a host of legendary faculty affiliated with the Center for International Studies were crucial early adopt- East Asia Expert Joins CIS ers and innovators of the games. -

Spring-2003-Part 1-Live

NIEMAN REPORTS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL.57 NO.1 SPRING 2003 Five Dollars Reporting on Health Investigating Scandal in the Catholic Church Journalists Testifying at War Crimes Tribunals “… to promote and elevate the standards of journalism” —Agnes Wahl Nieman, the benefactor of the Nieman Foundation. Vol. 57 No. 1 NIEMAN REPORTS Spring 2003 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY Publisher Bob Giles Editor Melissa Ludtke Assistant Editor Lois Fiore Editorial Assistant Elizabeth Son Design Editor Deborah Smiley Nieman Reports (USPS #430-650) is published Please address all subscription correspondence to in March, June, September and December One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098 by the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University, and change of address information to One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098. P.O. Box 4951, Manchester, NH 03108. ISSN Number 0028-9817 Telephone: (617) 496-2968 Second-class postage paid E-Mail Address (Business): at Boston, Massachusetts, [email protected] and additional entries. E-Mail Address (Editorial): POSTMASTER: [email protected] Send address changes to Nieman Reports, Internet Address: P.O. Box 4951, www.Nieman.Harvard.edu Manchester, NH 03108. Copyright 2003 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Subcription $20 a year, $35 for two years; add $10 per year for foreign airmail. Single copies $5. Back copies are available from the Nieman office. Vol. 57 No. 1 NIEMAN REPORTS Spring 2003 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY 5 Reporting on Health 7 Frustrations on the Frontlines of the Health Beat BY ANDREW HOLTZ 10 The Public Health Beat: What Is It? Why Is It Important? BY M.A.J. -

“...No Press Is Truly Free Unless Women Share an Equal Voice...”

“...No press is truly free unless women share an equal voice...” International Women’s Media Foundation Annual Report 2003/2004 Contents Letter from the IWMF Co-Chairs 3 About the IWMF 4 IWMF Programs 6 Courage in Journalism 8 Supporters 12 Financials 14 Contents 1 From the Co-Chairs The IWMF’s mission is to elevate the status of women The IWMF’s programs in Africa continue to be a in the news media, based on the belief that no press is primary focus. In 2003-2004, the IWMF held a truly free unless women share an equal voice. We seek training session on the New Economic Partnership to achieve that mission around the world by training for African Development (NEPAD). Working with women journalists and by supporting a world-wide a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, free press. the IWMF also created the Maisha Yetu (“Our Lives” in Swahili) program. To launch the program, we Since its founding in 1990, the IWMF has conducted conducted research in five African countries with the training programs on five continents and in 28 goal of analyzing the media’s coverage of HIV/AIDS, countries. In many of these locations, IWMF- TB and malaria. The results were published in sponsored programs are the only training opportunities September 2004 under the title Deadline for Health: offered exclusively to women journalists. The Media’s Response to Covering HIV/AIDS, TB and Malaria in Africa. (For the online version, go to In 2003-2004, we added a new online training http://www.awmc.com/pub/p-8392/e-8393/.) The module, Building Your Influence in the Newsroom, IWMF now is providing technical assistance to six to our website, www.iwmf.org. -

Annual Report 2011

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting PULITZER CENTER ON CRISIS REPORTING | ANNUAL REPORT 2011 | 1 We will illuminate “dark places and, with a deep sense of responsibility, interpret these troubled times. JOSEPH PULITZER III (1913-1993)” Founded in 2006, the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting is a leader in sponsoring Pulitzer Center on the independent journalism that media organizations are increasingly less able to Crisis Reporting undertake on their own. The Pulitzer Center’s mission is to raise the standard of coverage of global affairs and to do so in a way that engages the broad public and 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW government policy-makers. Suite 615 Washington, DC 20036 The Pulitzer Center is a bold initiative, in keeping with its sponsorship by a family whose name for more than a century has been a watchword for journalistic 202-332-0982 independence, integrity and courage. The Center is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. www.pulitzercenter.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from Board Chair and 3 Executive Director 2011 Reporting Projects 6 Global Gateway 12 Campus Consortium 16 Event Highlights 19 Awards and Honors 20 Staff, Board of Directors and 22 Advisory Council Donors 23 ” Contact Information and Credits 24 PULITZER CENTER ON CRISIS REPORTING | ANNUAL REPORT 2011 | 1 one on water and sanitation in West Africa and the second on reproductive health issues across Africa. Each pairs an international journalist with local journalists recruited from African countries. LETTER FROM BOARD CHAIR Thanks to a generous group of diverse donors we had the opportunity in 2011 to expand greatly our coverage of gold, AND EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR oil and other extractive industries as well as commodities in general. -

The Foreign Correspondent

[ABCDE] VOLUME 6, ISSUE 9 BY LUCIAN PERKINS — THE washington post A man holds out flowers as he leaves Basra, Iraq, while a British armored vehicle heads toward the city. The photo accompanied a story by Washington Post Foreign Editor Keith Richburg, who reported from the embattled country. The Foreign Correspondent A Look at the Journalists Who Provide Eyewitness Accounts, On-Sight Interviews And Reports of the Trends, Events and Ideas From Around the World. INSIDE Post Foreign Meet the Foreign Demise of Anguish in the Bureaus Correspondent the Foreign Ruins 3 7 12 Correspondent 16 June 5, 2007 © 2007 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 6, ISSUE 9 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program A Word About The Foreign Correspondent Lesson: The foreign correspondent Having a global understanding is essential to being an provides an eyewitness account, educated individual and an informed leader. From locating on-sight interviews and reports a visitor’s homeland on a map to having knowledge of the of trends, events and ideas from culture, economy and political situation of another country, places around the world. This global students are better citizens of an interconnected world. understanding is essential to being This guide focuses on the foreign correspondents who an educated individual and informed leader. provide eyewitness accounts, on-sight interviews and reports of the trends, events and ideas from locations around Level: Low to high the world. An interview with the Post’s Foreign Editor Keith Richburg and two articles written by experienced Subjects: Journalism, Geography, reporters provide the foundation for understanding the Business job of the foreign correspondent.