In This Issue Précisinterview: James E Baker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jonathan Capehart

Jonathan Capehart Award-winning journalist Jonathan Capehart is anchor of The Sunday Show with Jonathan Capehart on MSNBC and also an opinion writer and member of the editorial board of The Washington Post, where he hosts the podcast, Cape Up. In 1999, he was on the editorial board at the New York Daily News that won a Pulitzer Prize for the paper’s series of editorials that helped save Harlem’s Apollo Theater. He was also named an Esteem Honoree in 2011. In 2014, The Advocate magazine ranked him nineth out of fifty of the most influential LGBT people in media. In December 2014, Mediaite named him one of the “Top Nine Rising Stars of Cable News.” Equality Forum made him a 2018 LGBT History Month Icon in October. In May 2018, the publisher of the Washington Post awarded him an “Outstanding Contribution Award” for his opinion writing and “Cape Up” podcast interviews. Mr. Capehart first worked as assistant to the president of the WNYC Foundation. He then became a researcher for NBC's The Today Show. From 1993 to 2000, he served as a member of the New York Daily News’ editorial board. Mr. Capehart then went on to work as a national affairs columnist for Bloomberg News from 2000 to 2001, and later served as a policy advisor for Michael Bloomberg in his successful 2001 campaign for Mayor of New York City. In 2002, he returned to the New York Daily News, where he worked as deputy editorial page editor until 2004, when he was hired as senior vice president and senior counselor of public affairs for Hill & Knowlton. -

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech

Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech David Supp-Montgomerie A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication Studies in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Christian Lundberg V. William Balthrop Carole Blair Lawrence Grossberg William Keith © 2013 David Supp-Montgomerie ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT David Supp-Montgomerie: Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech (Under the direction of Christian Lundberg) This dissertation is a critique of the idea that the artifice of public speech is a problem to be solved. This idea is shown to entail the privilege attributed to purportedly direct or unmediated speech in U.S. public culture. I propose that we attend to the ēthos producing effects of rhetorical concealment by asserting that all public speech is constituted through rhetorical artifice. Wherever an alternative to rhetoric is offered, one finds a rhetoric of non-rhetoric at work. A primary strategy in such rhetoric is the performance of sincerity. In this dissertation, I analyze the function of sincerity in contexts of public deliberation. I seek to show how claims to sincerity are strategic, demonstrate how claims that a speaker employs artifice have been employed to imply a lack of sincerity, and disabuse communication, rhetoric, and deliberative theory of the notion that sincere expression occurs without technology. In Chapter Two I begin with the original problem of artifice for rhetoric in classical Athens in the writings of Plato and Isocrates. -

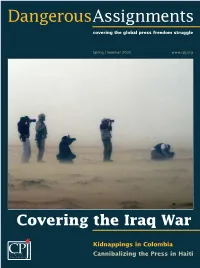

DA Spring 03

DangerousAssignments covering the global press freedom struggle Spring | Summer 2003 www.cpj.org Covering the Iraq War Kidnappings in Colombia Committee to·Protect Cannibalizing the Press in Haiti Journalists CONTENTS Dangerous Assignments Spring|Summer 2003 Committee to Protect Journalists FROM THE EDITOR By Susan Ellingwood Executive Director: Ann Cooper History in the making. 2 Deputy Director: Joel Simon IN FOCUS By Amanda Watson-Boles Dangerous Assignments Cameraman Nazih Darwazeh was busy filming in the West Bank. Editor: Susan Ellingwood Minutes later, he was dead. What happened? . 3 Deputy Editor: Amanda Watson-Boles Designer: Virginia Anstett AS IT HAPPENED By Amanda Watson-Boles Printer: Photo Arts Limited A prescient Chinese free-lancer disappears • Bolivian journalists are Committee to Protect Journalists attacked during riots • CPJ appeals to Rumsfeld • Serbia hamstrings Board of Directors the media after a national tragedy. 4 Honorary Co-Chairmen: CPJ REMEMBERS Walter Cronkite Our fallen colleagues in Iraq. 6 Terry Anderson Chairman: David Laventhol COVERING THE IRAQ WAR 8 Franz Allina, Peter Arnett, Tom Why I’m Still Alive By Rob Collier Brokaw, Geraldine Fabrikant, Josh A San Francisco Chronicle reporter recounts his days and nights Friedman, Anne Garrels, James C. covering the war in Baghdad. Goodale, Cheryl Gould, Karen Elliott House, Charlayne Hunter- Was I Manipulated? By Alex Quade Gault, Alberto Ibargüen, Gwen Ifill, Walter Isaacson, Steven L. Isenberg, An embedded CNN reporter reveals who pulled the strings behind Jane Kramer, Anthony Lewis, her camera. David Marash, Kati Marton, Michael Massing, Victor Navasky, Frank del Why I Wasn’t Embedded By Mike Kirsch Olmo, Burl Osborne, Charles A CBS correspondent explains why he chose to go it alone. -

Trump's Generals

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE Trump’s Generals: A Natural Experiment in Civil-Military Relations JAMES JOYNER Abstract President Donald Trump’s filling of numerous top policy positions with active and retired officers he called “my generals” generated fears of mili- tarization of foreign policy, loss of civilian control of the military, and politicization of the military—yet also hope that they might restrain his worst impulses. Because the generals were all gone by the halfway mark of his administration, we have a natural experiment that allows us to com- pare a Trump presidency with and without retired generals serving as “adults in the room.” None of the dire predictions turned out to be quite true. While Trump repeatedly flirted with civil- military crises, they were not significantly amplified or deterred by the presence of retired generals in key roles. Further, the pattern continued in the second half of the ad- ministration when “true” civilians filled these billets. Whether longer-term damage was done, however, remains unresolved. ***** he presidency of Donald Trump served as a natural experiment, testing many of the long- debated precepts of the civil-military relations (CMR) literature. His postelection interviewing of Tmore than a half dozen recently retired four- star officers for senior posts in his administration unleashed a torrent of columns pointing to the dangers of further militarization of US foreign policy and damage to the military as a nonpartisan institution. At the same time, many argued that these men were uniquely qualified to rein in Trump’s worst pro- clivities. With Trump’s tenure over, we can begin to evaluate these claims. -

This March 19, 2012 Al Sharpton Show

Page 1 7 of 13 DOCUMENTS Copyright 2012 Roll Call, Inc. All Rights Reserved MSNBC SHOW: POLITICS NATION 6:00 PM EST March 19, 2012 Monday TRANSCRIPT: 031901cb.472 SECTION: NEWS; Domestic LENGTH: 6505 words HEADLINE: POLITICS NATION for March 19, 2012 BYLINE: Al Sharpton GUESTS: Jonathan Capehart; Tracy Martin; Benjamin Crump, Steve Kornacki, Erin McPike, Michelle Caddell, Michael Blevins, Eric Zillmer BODY: REVEREND AL SHARPTON, MSNBC HOST: Welcome to "Politics Nation. I`m Al Sharpton. Tonight`s lead, the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin is parking on national outcry for justice. Three weeks ago the high school junior was shot and killed walking back to his father`s girlfriend`s house in a gated community near Orlando. But still, there has been no arrest even though the police know who shot him. George Zimmerman, the neighborhood watch captain, says he shot in self-defense. But the young man was unarmed. He was going home after buying an iced tea and skittles candy. In a minute, we will talk with Trayvon`s father and family lawyer and we will get a live report from the scene. But first, the police have now finally released the 911 tapes in the case, and it contained a shocking heart-breaking picture of what happened that rainy night of February 26th and they cry out for justice to be done in the case. Here is the call that George Zimmerman, the shooter, made to police. (BEGIN AUDIOTAPE) 911 DISPATCHER: Sanford police department. Page 2 POLITICS NATION for March 19, 2012 MSNBC March 19, 2012 Monday GEORGE ZIMMERMAN, SUSPECT IN TRAYVON`S MARTIN`S KILLING: Hey, we have had some break-ins in my neighborhood, and there is a real suspicious guy that looks like he is up to no good or on drugs or something. -

The Kosovo Report

THE KOSOVO REPORT CONFLICT v INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE v LESSONS LEARNED v THE INDEPENDENT INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON KOSOVO 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford Executive Summary • 1 It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, Address by former President Nelson Mandela • 14 and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Map of Kosovo • 18 Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Introduction • 19 Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw PART I: WHAT HAPPENED? with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Preface • 29 Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the uk and in certain other countries 1. The Origins of the Kosovo Crisis • 33 Published in the United States 2. Internal Armed Conflict: February 1998–March 1999 •67 by Oxford University Press Inc., New York 3. International War Supervenes: March 1999–June 1999 • 85 © Oxford University Press 2000 4. Kosovo under United Nations Rule • 99 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) PART II: ANALYSIS First published 2000 5. The Diplomatic Dimension • 131 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, 6. International Law and Humanitarian Intervention • 163 without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, 7. Humanitarian Organizations and the Role of Media • 201 or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

Programming Notes - First Read

Programming notes - First Read Hotmail More TODAY Nightly News Rock Center Meet the Press Dateline msnbc Breaking News EveryBlock Newsvine Account ▾ Home US World Politics Business Sports Entertainment Health Tech & science Travel Local Weather Advertise | AdChoices Recommended: Recommended: Recommended: 3 Recommended: First Thoughts: My, VIDEO: The Week remaining First Thoughts: How New iPads are Selling my, Myanmar That Was: Gifts, undecided House Rebuilding time for Under $40 fiscal cliff, and races verbal fisticuffs How Cruise Lines Fill All Those Unsold Cruise Cabins What Happens When You Take a Testosterone The first place for news and analysis from the NBC News Political Unit. Follow us on Supplement Twitter. ↓ About this blog ↓ Archives E-mail updates Follow on Twitter Subscribe to RSS Like 34k 1 comment Recommend 3 0 older3 Programming notes newer days ago *** Friday's "The Daily Rundown" line-up with guest host Luke Russert: NBC's Kelly O'Donnell on Petraeus' testimony… NBC's Ayman Mohyeldin live in Gaza… one of us (!!!) with more on the Republican reaction to Romney… NBC's Mike Viqueira on today's White House meeting on the fiscal cliff and The Economist's Greg Ip and National Journal's Jim Tankersley on the "what ifs" surrounding the cliff… New NRCC Chairman Rep. Greg Walden (R-OR) on the House GOP's road forward… Democratic strategist Doug Thornell, Roll Call's David Drucker and the New York Times' Jackie Calmes on how the next round of negotiations could be different (or all too similar) to the last time. Advertise | AdChoices *** Friday’s “Jansing & How to Improve Memory E-Cigarettes Exposed: Stony Brook Co.” line-up: MSNBC’s Chris with Scientifically Designed The E-Cigarette craze is sweeping the country. -

Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2018 Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the American Politics Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Political Theory Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Hopper, Hannah, "Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3402. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3402 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Media and Communication East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Brand and Media Strategy _____________________ by Hannah Hopper May 2018 _____________________ Dr. Susan E. Waters, Chair Dr. Melanie Richards Dr. Phyllis Thompson Keywords: Political Journalist, Twitter, Agenda Setting, Framing, Gatekeeping, Feminist Political Theory, Political Polarization, Presidential Debate, Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump ABSTRACT Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate by Hannah Hopper Past research shows that journalists are gatekeepers to information the public seeks. -

AGENDA June 3 – 4, 2017

Pulitzer Center Pulitzer Center Gender Lens Conference Gender Lens Conference June 3 – 4, 2017 AGENDA June 3 – 4, 2017 Saturday, June 3, 2017 2:00-2:30 Registration 2:30-3:45 Concurrent panels 1) Women in Conflict Zones Welcome: Tom Hundley, Pulitzer Center Senior Editor • Susan Glasser, Politico chief international affairs columnist and host of The Global Politico (moderator) • Paula Bronstein, freelance photojournalist (G) • Sarah Holewinski, senior fellow, Center for a New American Security, board member, Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) • Sarah Topol, freelance journalist (G) • Cassandra Vinograd, freelance journalist (G) 2) Property Rights Welcome: Steve Sapienza, Pulitzer Center Senior Producer • LaShawn Jefferson, deputy director, Perry World House, University of Pennsylvania (moderator) • Amy Toensing, freelance photojournalist (G) • Paola Totaro, editor, Thomson Reuters Foundation’s Place • Nana Ama Yirrah, founder, COLENDEF 3) Global Health • Rebecca Kaplan, Mellon/ACLS Public Fellow at the Pulitzer Center (moderator) • Jennifer Beard, Clinical Associate Professor, Boston University School of Public Health (Pulitzer Center Campus Consortium partner) • Caroline Kouassiaman, senior program officer, Sexual Health and Rights, American Jewish World Service (AJWS) • Allison Shelley, freelance photojournalist (G) • Rob Tinworth, filmmaker (G) 4:00-4:30 Coffee break 4:30-5:45 Concurrent panels 1) Diversifying the Story • Yochi Dreazen, foreign editor of Vox.com (moderator) (G) • Kwame Dawes, poet, writer, actor, musician, professor -

Joe Fryer to Host Transamerica, One-Hour Special on Nbc News Now Examining Issues Facing the Transgender Community on June 17

JOE FRYER TO HOST TRANSAMERICA, ONE-HOUR SPECIAL ON NBC NEWS NOW EXAMINING ISSUES FACING THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY ON JUNE 17 • NBC News NOW will stream TRANSAMERICA, hosted by Morning News NOW co-host Joe Fryer at 8 p.m. ET on June 17, examining state laws discriminating against transgender Americans and showcasing stories of transgender lawmakers making a difference in their communities. Fryer will also interview parents of transgender children and will moderate an anti-violence panel to discuss what can be done to raise awareness and help prevent crimes against the transgender community. The special will also examine the mental health challenges that many in the transgender community face from the pressure, stigma, and fears of everyday society that does not accept or understand them. Additionally, previews of the special will air on TODAY and Nightly News with Lester Holt. TODAY, NBC NIGHTLY NEWS, AND MEET THE PRESS TO HIGHLIGHT PRIDE CELEBRATIONS, SPOTLIGHT LGBTQ TRAILBLAZERS OF THE PAST AND PRESENT AND EXPLORE THE EVOLUTION OF LGBTQ SUPPORT • On TODAY, Joe Fryer will take a deep-dive look at Pride celebrations taking place this year and will explore how LGBTQ bars across the country are approaching reopening. Plus, marking 40 years since the first reported case of HIV/AIDS, Fryer will report on the historical, scientific, and cultural impact of the virus as well as advances in prevention and treatment. • Throughout the month,Deadline TODAY will highlight a variety of inspiring stories and perspectives of the LGBTQ experience including: the first gay married couple in the U.S. fifty years ago, Jack Baker and Michael McDonnel, discuss the story that inspired the book “Two Grooms on a Cake”; SNL’s Bowen Yang reflects on coming out and how the process has changed; actresses Indya Moore and Angelic Ross of FX’s Pose reflect on the pioneering nature of the series and its final close this summer; and more. -

Making Black and Brown Lives Matter: Incorporating Race Into the Criminal Procedure Curriculum

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 60 Number 3 Teaching Criminal Procedure (Spring Article 7 2016) 2016 Making Black and Brown Lives Matter: Incorporating Race Into the Criminal Procedure Curriculum Cynthia Lee George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Cynthia Lee, Making Black and Brown Lives Matter: Incorporating Race Into the Criminal Procedure Curriculum, 60 St. Louis U. L.J. (2016). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol60/iss3/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW MAKING BLACK AND BROWN LIVES MATTER: INCORPORATING RACE INTO THE CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CURRICULUM CYNTHIA LEE* The fatal shooting of Michael Brown, an African American teenager, in August 2014 by a White police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, and the death of Eric Garner, an African American man who died after being put into a chokehold by a New York City police officer in July 2014, led to a firestorm of protests under the moniker of “Black Lives Matter.”1 Many Blacks saw these two deaths and the failure to indict the officers involved as reflecting a lack of concern for Black lives.2 * Cynthia Lee is the Charles Kennedy Poe Research Professor of Law, The George Washington University Law School, and the author of MURDER AND THE REASONABLE MAN: PASSION AND FEAR IN THE CRIMINAL COURTROOM (N.Y.