Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 6, 2007 No. 22 House of Representatives The House met at 10:30 a.m. and was become true. It is Orwellian double- committee of initial referral has a called to order by the Speaker pro tem- think, an amazing concept. statement that the proposition con- pore (Mr. JOHNSON of Georgia). They believe that if you simply just tains no congressional earmarks. So f say you are lowering drug prices, poof, the chairman of the Appropriations it’s done, ignoring the reality that Committee, Mr. OBEY, conveniently DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO prices really won’t be lowered and submitted to the record on January 29 TEMPORE fewer drugs will be made available to that prior to the omnibus bill being The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- our seniors. considered, quote, ‘‘does not contain fore the House the following commu- They believe that if you just say you any congressional earmarks, limited nication from the Speaker: are implementing all of the 9/11 Com- tax benefits, or limited tariff benefits.’’ WASHINGTON, DC, mission’s recommendations, it changes But, in fact, Mr. Speaker, this omnibus February 6, 2007. the fact that the bill that was passed spending bill that the Democrats I hereby appoint the Honorable HENRY C. here on the floor doesn’t reflect the to- passed last week contained hundreds of ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, Jr. to act as Speaker pro tality of those recommendations. -

Contemporary Conservative Constructions of American Exceptionalism

Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, Vol. 1, No.2, 2011, pp. 40-54. Contemporary Conservative Constructions of American Exceptionalism Jason A. Edwards Ever since President Obama took office in 2009, there has been an underlying debate amongst politicians, pundits, and policymakers over America’s exceptionalist nature. American exceptionalism is one of the foundational myths of U.S. identity. While analyses of Barack Obama’s views on American exceptionalism are quite prominent, there has been little discussion of conservative rhetorical constructions of this impor- tant myth. In this essay, I seek to fill this gap by mapping prominent American conservatives’ rhetorical voice on American exceptionalism. Keywords: American exceptionalism, conservative rhetoric, jeremiad In April 2009, President Obama travelled to Europe to meet with European leaders in coordinating a strategy to deal with the global financial crisis and to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the NATO alliance. At a news conference in Strasbourg, France, Ed Luce of the Financial Times asked the president whether or not he believed in American ex- ceptionalism. Obama answered by stating, I believe in American exceptionalism, just as I suspect that the Brits believe in British ex- ceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism. I am enormously proud of my country and its role and history in the world . we have a core set of values that are en- shrined in our Constitution, in our body of law, in our democratic practices, in our belief in free speech and equality that, though imperfect, are exceptional. Now, the fact that I am very proud of my country and I think that we‟ve got a whole lot to offer the world does not lessen my interest in recognizing the value and wonderful qualities of other countries or recogniz- ing that we‟re not always going to be right, or that people may have good ideas, or that in order for us to work collectively, all parties, have to compromise, and that includes us. -

House Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JUNE 21, 2005 No. 83 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was I would like to read an e-mail that there has never been a worse time for called to order by the Speaker pro tem- one of my staffers received at the end Congress to be part of a campaign pore (Miss MCMORRIS). of last week from a friend of hers cur- against public broadcasting. We formed f rently serving in Iraq. The soldier says: the Public Broadcasting Caucus 5 years ‘‘I know there are growing doubts, ago here on Capitol Hill to help pro- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO questions and concerns by many re- mote the exchange of ideas sur- TEMPORE garding our presence here and how long rounding public broadcasting, to help The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- we should stay. For what it is worth, equip staff and Members of Congress to fore the House the following commu- the attachment hopefully tells you deal with the issues that surround that nication from the Speaker: why we are trying to make a positive important service. difference in this country’s future.’’ There are complexities in areas of le- WASHINGTON, DC, This is the attachment, Madam June 21, 2005. gitimate disagreement and technical I hereby appoint the Honorable CATHY Speaker, and a picture truly is worth matters, make no mistake about it, MCMORRIS to act as Speaker pro tempore on 1,000 words. -

Jonathan Capehart

Jonathan Capehart Award-winning journalist Jonathan Capehart is anchor of The Sunday Show with Jonathan Capehart on MSNBC and also an opinion writer and member of the editorial board of The Washington Post, where he hosts the podcast, Cape Up. In 1999, he was on the editorial board at the New York Daily News that won a Pulitzer Prize for the paper’s series of editorials that helped save Harlem’s Apollo Theater. He was also named an Esteem Honoree in 2011. In 2014, The Advocate magazine ranked him nineth out of fifty of the most influential LGBT people in media. In December 2014, Mediaite named him one of the “Top Nine Rising Stars of Cable News.” Equality Forum made him a 2018 LGBT History Month Icon in October. In May 2018, the publisher of the Washington Post awarded him an “Outstanding Contribution Award” for his opinion writing and “Cape Up” podcast interviews. Mr. Capehart first worked as assistant to the president of the WNYC Foundation. He then became a researcher for NBC's The Today Show. From 1993 to 2000, he served as a member of the New York Daily News’ editorial board. Mr. Capehart then went on to work as a national affairs columnist for Bloomberg News from 2000 to 2001, and later served as a policy advisor for Michael Bloomberg in his successful 2001 campaign for Mayor of New York City. In 2002, he returned to the New York Daily News, where he worked as deputy editorial page editor until 2004, when he was hired as senior vice president and senior counselor of public affairs for Hill & Knowlton. -

1 in the United States District Court for the District

6:10-cv-01884-JMC Date Filed 07/20/10 Entry Number 1 Page 1 of 23 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA GREENVILLE DIVISION TIM CLARK, JOHANNA CLOUGHERTY, CIVIL ACTION MICHAEL CLOUGHERTY, on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated, Plaintiffs, v. CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT GOLDLINE INTERNATIONAL, INC., Defendant. I. NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Plaintiffs and proposed class representatives Tim Clark, Johanna Clougherty, and Michael Clougherty (“Plaintiffs”) bring this action individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated against Defendant Goldline International, Inc. (“Goldline”) to recover damages arising from Goldline’s violation of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (“RICO”), 18 U.S.C. § 1961, et seq., unfair and deceptive trade practices, and unjust enrichment. 2. This action is brought as a class action pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 on behalf of a Class, described more fully below, which includes all persons or entities domiciled or residing in any of the fifty states of the United States of America or in the District of Columbia who purchased at least one product from Goldline since July 20, 2006. 3. Goldline is a precious metal dealer that buys and sells numismatic coins and bullion to investors and collectors all across the nation via telemarketing and telephone sales. Goldline is an established business that has gained national prominence in recent years through its association with conservative talk show hosts it sponsors and paid celebrity spokespeople who 1 6:10-cv-01884-JMC Date Filed 07/20/10 Entry Number 1 Page 2 of 23 have agreed to promote Goldline products by playing off the fear of inflation to encourage people to purchase gold and other precious metals as an investment that will protect them from an out of control government. -

Dear Peace and Justice Activist, July 22, 1997

Peace and Justice Awardees 1995-2006 1995 Mickey and Olivia Abelson They have worked tirelessly through Cambridge Sane Free and others organizations to promote peace on a global basis. They’re incredible! Olivia is a member of Cambridge Community Cable Television and brings programming for the local community. Rosalie Anders Long time member of Cambridge Peace Action and the National board of Women’s Action of New Dedication for (WAND). Committed to creating a better community locally as well as globally, Rosalie has nurtured a housing coop for more than 10 years and devoted loving energy to creating a sustainable Cambridge. Her commitment to peace issues begin with her neighborhood and extend to the international. Michael Bonislawski I hope that his study of labor history and workers’ struggles of the past will lead to some justice… He’s had a life- long experience as a member of labor unions… During his first years at GE, he unrelentingly held to his principles that all workers deserve a safe work place, respect, and decent wages. His dedication to the labor struggle, personally and academically has lasted a life time, and should be recognized for it. Steve Brion-Meisels As a national and State Board member (currently national co-chair) of Peace Action, Steven has devoted his extraordinary ability to lead, design strategies to advance programs using his mediation skills in helping solve problems… Within his neighborhood and for every school in the city, Steven has left his handiwork in the form of peaceable classrooms, middle school mediation programs, commitment to conflict resolution and the ripping effects of boundless caring. -

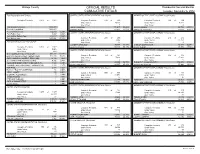

Official Results Cumulative Totals

Orange County OFFICIAL RESULTS Presidential General Election CUMULATIVE TOTALS Tuesday, November 6, 2012 Total Registration and Turnout UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 45th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 55th District Complete Precincts: 1,977 of 1,977 Complete Precincts: 519 of 519 Complete Precincts: 160 of 160 Under Votes: 19,555 Under Votes: 8,377 Over Votes: 7 Over Votes: 4 Total Registered Voters 1,683,001 JOHN CAMPBELL 171,417 58.46% CURT HAGMAN 56,736 65.39% Precinct Registration 1,683,001 SUKHEE KANG 121,814 41.54% GREGG D. FRITCHLE 30,033 34.61% Precinct Ballots Cast 552,018 32.80% UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 46th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 65th District Early Ballots Cast 5,343 0.32% Vote-by-Mail Ballots Cast 575,843 34.22% Total Ballots Cast 1,133,204 67.33% Complete Precincts: 290 of 290 Complete Precincts: 276 of 276 Under Votes: 7,682 Under Votes: 11,167 PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT Over Votes: 17 Over Votes: 8 LORETTA SANCHEZ 95,694 63.87% SHARON QUIRK-SILVA 68,988 52.04% Complete Precincts: 1,977 of 1,977 JERRY HAYDEN 54,121 36.13% CHRIS NORBY 63,576 47.96% Under Votes: 9,926 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 47th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 68th District Over Votes: 614 MITT ROMNEY PAUL RYAN (REP) 582,332 51.87% BARACK OBAMA JOSEPH BIDEN (DEM) 512,440 45.65% Complete Precincts: 184 of 184 Complete Precincts: 345 of 345 7,648 17,944 GARY JOHNSON JAMES P. GRAY (LIB) 14,132 1.26% Under Votes: Under Votes: 5 6 JILL STEIN CHERI HONKALA (GRN) 4,792 0.43% Over Votes: Over Votes: 49,599 54.72% 104,706 60.82% ROSEANNE BARR CINDY SHEEHAN (P-F) 3,348 0.30% GARY DELONG DONALD P. -

Speech Error Expressions in Maliki National Debate Tournament (Mandate) 2015

SPEECH ERROR EXPRESSIONS IN MALIKI NATIONAL DEBATE TOURNAMENT (MANDATE) 2015 THESIS By: MUHAMMAD RYDZKY MUHAMMAD ALI NIM 12320079 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES THE ISLAMIC STATE UNIVERSITY MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2017 SPEECH ERROR EXPRESSIONS IN MALIKI NATIONAL DEBATE TOURNAMENT (MANDATE) 2015 THESIS Presented to Maulana Malik Ibrahim State Islamic University of Malang in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra (S.S) By: MUHAMMAD RYDZKY MUHAMMAD ALI NIM 12320079 Advisor Dr. ROHMANI NUR INDAH, M.Pd. NIP 19760910 200312 2 003 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES THE ISLAMIC STATE UNIVERSITY MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2017 i ii iv v MOTTO قَا َل َر ِّب ا ْش َر ْح لِي َص ْد ِري )52( َويَ ِّس ْر لِي أَ ْم ِري )52( َوا ْحلُ ْل ُع ْق َدةً ِم ْن لِ َسانِي )52( يَ ْفقَهُوا قَ ْولِي )52 Musa said, "Allah, expand for me my breast [with assurance], and ease for me my task, and untie the knot from my tongue, that they may understand my speech. (QS. Thoha: 25-28) vi DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to: My beloved father and mother, Muhammad Ali Hamzah and Abida Yakob Saman. I hope that it could make them proud. It is also for my beloved brother Fitrianto Muhammad Ali and Muhammad Ali Family who always support me. Thank you for my wife, Dian Purwitasari, for helping me finishing this work. vii ACKNOWLEDGMENT All praises are to Allah, who has given power, inspiration, and health in finishing the thesis. All my hopes and wishes are only for him. -

Accuracy in the Detection of Deception As a Function of Training in the Study of Human Behavior

University of Central Florida STARS Retrospective Theses and Dissertations 1976 Accuracy in the Detection of Deception as a Function of Training in the Study of Human Behavior Charner Powell Leone University of Central Florida Part of the Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/rtd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Leone, Charner Powell, "Accuracy in the Detection of Deception as a Function of Training in the Study of Human Behavior" (1976). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 230. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/rtd/230 ACCURACY IN THE DETECTION OF DECEPTION AS A FUNCTION OF TRAINING I N· ·T"H E STU 0 Y 0 F HUMAN BE HA V I 0 R BY CHARNER POWELL LEONE B.S.J., University of Florida, 1967 THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts: Communication in the Graduate Studies Program of the College of Social Sciences Florida Technological University Orlando, Florida 1976 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . i v INTRODUCTION . 1 METHODOLOGY . 12 Subjects . 12 Procedure and Materials . 12 RESULTS . 1 7 DISCUSSION . ~ 26 SUMMARY . 34 APPENDIX A. Questionnaire . 37 APPENDIX 8 • Judge•s Scoresheets . 39 REFERENCES . 44 i i LIST OF TABLES TABLE Page 1 Mean Behaviors Used to Discriminate Lying from Truthful Role Players by Decoder Groups . -

Persuasion in the Art of Preaching for the Church

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project Concordia Seminary Scholarship 5-1-1991 Persuasion in the Art of Preaching for the Church William Matzat Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Matzat, William, "Persuasion in the Art of Preaching for the Church" (1991). Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project. 88. https://scholar.csl.edu/dmin/88 This Major Applied Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROLOGUE INTRODUCTION iii SECTION ONE CHAPTER 1 PROCLAIMING THE WORD OF GOD FOR THE CHURCH 2 CHAPTER 2 CONNECTING THE PROCLAMATION WITH THE LIFE OF THE HEARER 22 CHAPTER 3 APPLYING LAW AND GOSPEL TO THE HEARER 41 SECTION TWO 54 CHAPTER 4 PERSUASION UNDERSTOOD BY THE ANCIENT AND CONTEMPORARY WORLD 55 CHAPTER 5 PERSUASION IS BASED ON THE TRANSACTION OF THE PROCLAINDE WITH THE HEARER 68 CHAPTER 6 PERSUASION IS IMPLEMENTED BY THE SPIRIT OF GOD 88 SECTION THREE 105 CHAPTER 7 ANALYZING THE PREACHING TASK TODAY 106 CHAPTER 8 EVALUATING THE PREACHING TASK FOR THE CHURCH 122 CHAPTER 9 THE SHARED RESPONSIBILITY OF PREACHING 139 THE CONCLUSION 146 BIBLIOGRAPHY 147 APPENDIX A 151 APPENDIX B 153 APPENDIX C 154 APPENDIX D 155 PROLOGUE THE SOWER REVISITED: A PARABLE As the sun brightened the field and warmed the face of the farmer, he sowed the good seed with rhythmic motion and head held high. -

Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research the Dynamics of Wordplay

Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research The Dynamics of Wordplay Edited by Esme Winter-Froemel Editorial Board Salvatore Attardo, Dirk Delabastita, Dirk Geeraerts, Raymond W. Gibbs, Alain Rabatel, Monika Schmitz-Emans and Deirdre Wilson Volume 6 Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research Edited by Esme Winter-Froemel and Verena Thaler The conference “The Dynamics of Wordplay / La dynamique du jeu de mots – Interdisciplinary perspectives / perspectives interdisciplinaires” (Universität Trier, 29 September – 1st October 2016) and the publication of the present volume were funded by the German Research Founda- tion (DFG) and the University of Trier. Le colloque « The Dynamics of Wordplay / La dynamique du jeu de mots – Interdisciplinary perspectives / perspectives interdisciplinaires » (Universität Trier, 29 septembre – 1er octobre 2016) et la publication de ce volume ont été financés par la Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) et l’Université de Trèves. ISBN 978-3-11-058634-3 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-058637-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063087-9 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2018955240 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Esme Winter-Froemel and Verena Thaler, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Contents Esme Winter-Froemel, Verena Thaler and Alex Demeulenaere The dynamics of wordplay and wordplay research 1 I New perspectives on the dynamics of wordplay Raymond W. -

Trump's Generals

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE Trump’s Generals: A Natural Experiment in Civil-Military Relations JAMES JOYNER Abstract President Donald Trump’s filling of numerous top policy positions with active and retired officers he called “my generals” generated fears of mili- tarization of foreign policy, loss of civilian control of the military, and politicization of the military—yet also hope that they might restrain his worst impulses. Because the generals were all gone by the halfway mark of his administration, we have a natural experiment that allows us to com- pare a Trump presidency with and without retired generals serving as “adults in the room.” None of the dire predictions turned out to be quite true. While Trump repeatedly flirted with civil- military crises, they were not significantly amplified or deterred by the presence of retired generals in key roles. Further, the pattern continued in the second half of the ad- ministration when “true” civilians filled these billets. Whether longer-term damage was done, however, remains unresolved. ***** he presidency of Donald Trump served as a natural experiment, testing many of the long- debated precepts of the civil-military relations (CMR) literature. His postelection interviewing of Tmore than a half dozen recently retired four- star officers for senior posts in his administration unleashed a torrent of columns pointing to the dangers of further militarization of US foreign policy and damage to the military as a nonpartisan institution. At the same time, many argued that these men were uniquely qualified to rein in Trump’s worst pro- clivities. With Trump’s tenure over, we can begin to evaluate these claims.