Controlling the Wrath of Self-Representation: the ICTY's Crucial Trial of Radovan Karadžić

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money by Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss

The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money by Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss A Special Report presented by The Interpreter, a project of the Institute of Modern Russia imrussia.org interpretermag.com The Institute of Modern Russia (IMR) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan public policy organization—a think tank based in New York. IMR’s mission is to foster democratic and economic development in Russia through research, advocacy, public events, and grant-making. We are committed to strengthening respect for human rights, the rule of law, and civil society in Russia. Our goal is to promote a principles- based approach to US-Russia relations and Russia’s integration into the community of democracies. The Interpreter is a daily online journal dedicated primarily to translating media from the Russian press and blogosphere into English and reporting on events inside Russia and in countries directly impacted by Russia’s foreign policy. Conceived as a kind of “Inopressa in reverse,” The Interpreter aspires to dismantle the language barrier that separates journalists, Russia analysts, policymakers, diplomats and interested laymen in the English-speaking world from the debates, scandals, intrigues and political developments taking place in the Russian Federation. CONTENTS Introductions ...................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................... 6 Background ........................................................................ -

Justice to the Extent Possible: the Prospects for Accountability in Afghanistan

KHAN GALLEY 1.0 11/18/2010 5:40:51 PM JUSTICE TO THE EXTENT POSSIBLE: THE PROSPECTS FOR ACCOUNTABILITY IN AFGHANISTAN Nadia Khan* I. INTRODUCTION Justice in Afghanistan, in the wake of nearly three decades of war, is a com- plicated endeavor – further complicated by the Afghan government’s recent grant of amnesty to perpetrators of past crimes. This paper will attempt to establish the prospects for accountability in Afghanistan, in light of the country’s historical cy- cles of war and violence and the recent attempts to trade justice for peace. The his- torical foundation will first be laid to demonstrate the complexities of the Afghan conflict and the fragility of the current regime. The steps that have been taken to- wards establishing a transitional justice framework are then set out to illustrate the theoretical objectives that stand in sharp contrast to the government’s actual intran- sigence to justice and accountability. The latter being demonstrated most signifi- cantly in the amnesty law signed into effect on February 20, 2007, that may ulti- mately be considered illegal at international law. However, the illegality of amnesty does not answer the question of account- ability for Afghans, since current circumstances and the government’s self-interest suggest that it will continue in effect. Thus, alternatives are considered, both do- mestically and internationally – with only one avenue producing the most realistic prospect for justice and accountability. It suggests that justice in Afghanistan is not entirely impossible, in spite of the increasing instability and in spite of the am- nesty. Although the culture of impunity in Afghanistan has been perpetuated on the pretext of peace – it has become all too clear that true peace will require jus- tice. -

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

Russia's Hostile Measures in Europe

Russia’s Hostile Measures in Europe Understanding the Threat Raphael S. Cohen, Andrew Radin C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1793 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0077-2 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report is the collaborative and equal effort of the coauthors, who are listed in alphabetical order. The report documents research and analysis conducted through 2017 as part of a project entitled Russia, European Security, and “Measures Short of War,” sponsored by the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7, U.S. -

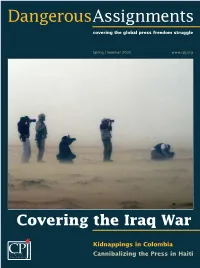

DA Spring 03

DangerousAssignments covering the global press freedom struggle Spring | Summer 2003 www.cpj.org Covering the Iraq War Kidnappings in Colombia Committee to·Protect Cannibalizing the Press in Haiti Journalists CONTENTS Dangerous Assignments Spring|Summer 2003 Committee to Protect Journalists FROM THE EDITOR By Susan Ellingwood Executive Director: Ann Cooper History in the making. 2 Deputy Director: Joel Simon IN FOCUS By Amanda Watson-Boles Dangerous Assignments Cameraman Nazih Darwazeh was busy filming in the West Bank. Editor: Susan Ellingwood Minutes later, he was dead. What happened? . 3 Deputy Editor: Amanda Watson-Boles Designer: Virginia Anstett AS IT HAPPENED By Amanda Watson-Boles Printer: Photo Arts Limited A prescient Chinese free-lancer disappears • Bolivian journalists are Committee to Protect Journalists attacked during riots • CPJ appeals to Rumsfeld • Serbia hamstrings Board of Directors the media after a national tragedy. 4 Honorary Co-Chairmen: CPJ REMEMBERS Walter Cronkite Our fallen colleagues in Iraq. 6 Terry Anderson Chairman: David Laventhol COVERING THE IRAQ WAR 8 Franz Allina, Peter Arnett, Tom Why I’m Still Alive By Rob Collier Brokaw, Geraldine Fabrikant, Josh A San Francisco Chronicle reporter recounts his days and nights Friedman, Anne Garrels, James C. covering the war in Baghdad. Goodale, Cheryl Gould, Karen Elliott House, Charlayne Hunter- Was I Manipulated? By Alex Quade Gault, Alberto Ibargüen, Gwen Ifill, Walter Isaacson, Steven L. Isenberg, An embedded CNN reporter reveals who pulled the strings behind Jane Kramer, Anthony Lewis, her camera. David Marash, Kati Marton, Michael Massing, Victor Navasky, Frank del Why I Wasn’t Embedded By Mike Kirsch Olmo, Burl Osborne, Charles A CBS correspondent explains why he chose to go it alone. -

International Court of Justice (ICJ)

SRMUN ATLANTA 2018 Our Responsibility: Facilitating Social Development through Global Engagement and Collaboration November 15 - 17, 2018 [email protected] Greetings Delegates, Welcome to SRMUN Atlanta 2018 and the International Court of Justice (ICJ). My name is Lydia Schlitt, and I will be serving as your Chief Justice for the ICJ. This will be my third conference as a SRMUN staff member. Previously, I served as the Director of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) at SRMUN Atlanta 2017 and the Assistant Director (AD) of the Group of 77 (G-77) at SRMUN Atlanta 2016. I am currently a Juris Doctorate candidate at the University of Oregon School of Law and hold a Bachelor’s of Science with Honors in Political Science and a minor in Mathematics from Berry College. Our committee’s Assistant Chief Justice will be Jessica Doscher. This will be Jessica’s second time as a staff member as last year she served as the AD for the General Assembly Plenary (GA Plen). Founded in 1945, the ICJ is the principal legal entity for the United Nations (UN). The ICJ’s purpose is to solve legal disputes at the request of Member States and other UN entities. By focusing on the SRMUN Atlanta 2018 theme of “Our Responsibility: Facilitating Social Development through Global Engagement and Collaboration," throughout the conference, delegates will be responsible for arguing on the behalf of their assigned position for the assigned case, as well as serving as a Justice for the ICJ for the remaining cases. The following cases will be debated: I. -

The Kosovo Report

THE KOSOVO REPORT CONFLICT v INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE v LESSONS LEARNED v THE INDEPENDENT INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON KOSOVO 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford Executive Summary • 1 It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, Address by former President Nelson Mandela • 14 and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Map of Kosovo • 18 Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Introduction • 19 Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw PART I: WHAT HAPPENED? with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Preface • 29 Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the uk and in certain other countries 1. The Origins of the Kosovo Crisis • 33 Published in the United States 2. Internal Armed Conflict: February 1998–March 1999 •67 by Oxford University Press Inc., New York 3. International War Supervenes: March 1999–June 1999 • 85 © Oxford University Press 2000 4. Kosovo under United Nations Rule • 99 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) PART II: ANALYSIS First published 2000 5. The Diplomatic Dimension • 131 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, 6. International Law and Humanitarian Intervention • 163 without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, 7. Humanitarian Organizations and the Role of Media • 201 or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

AGENDA June 3 – 4, 2017

Pulitzer Center Pulitzer Center Gender Lens Conference Gender Lens Conference June 3 – 4, 2017 AGENDA June 3 – 4, 2017 Saturday, June 3, 2017 2:00-2:30 Registration 2:30-3:45 Concurrent panels 1) Women in Conflict Zones Welcome: Tom Hundley, Pulitzer Center Senior Editor • Susan Glasser, Politico chief international affairs columnist and host of The Global Politico (moderator) • Paula Bronstein, freelance photojournalist (G) • Sarah Holewinski, senior fellow, Center for a New American Security, board member, Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) • Sarah Topol, freelance journalist (G) • Cassandra Vinograd, freelance journalist (G) 2) Property Rights Welcome: Steve Sapienza, Pulitzer Center Senior Producer • LaShawn Jefferson, deputy director, Perry World House, University of Pennsylvania (moderator) • Amy Toensing, freelance photojournalist (G) • Paola Totaro, editor, Thomson Reuters Foundation’s Place • Nana Ama Yirrah, founder, COLENDEF 3) Global Health • Rebecca Kaplan, Mellon/ACLS Public Fellow at the Pulitzer Center (moderator) • Jennifer Beard, Clinical Associate Professor, Boston University School of Public Health (Pulitzer Center Campus Consortium partner) • Caroline Kouassiaman, senior program officer, Sexual Health and Rights, American Jewish World Service (AJWS) • Allison Shelley, freelance photojournalist (G) • Rob Tinworth, filmmaker (G) 4:00-4:30 Coffee break 4:30-5:45 Concurrent panels 1) Diversifying the Story • Yochi Dreazen, foreign editor of Vox.com (moderator) (G) • Kwame Dawes, poet, writer, actor, musician, professor -

The Hague Espace for Environmental Global Governance

I NSTITUTE FOR E NVIRONMENTAL S ECURITY Study on The Hague Espace for Environmental Global Governance Wybe Th. Douma ❘ Leonardo Massai ❘ Serge Bronkhorst ❘ Wouter J. Veening Volume One - Report May 2009 STUDY ON THE HAGUE ESPACE FOR ENVIRONMENTAL GLOBAL GOVERNANCE VOLUME ONE - REPORT May 2009 Study on The Hague Espace for Environmental Global Governance Volume One - Report Authors: Wybe Th. Douma - Leonardo Massai - Serge Bronkhorst - Wouter J. Veening Published by: Institute for Environmental Security Anna Paulownastraat 103 2518 BC The Hague, The Netherlands Tel: +31 70 365 2299 ● Fax: +31 70 365 1948 www.envirosecurity.org In association with: T.M.C. Asser Institute P.O. Box 30461 2500 GL The Hague, The Netherlands Tel: +31 70 342 0300 ● Fax: +3170 342 0359 www.asser.nl With the support of: City of The Hague The Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs The Netherlands Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment Project Team: Wouter J. Veening, Chairman / President, IES Ronald A. Kingham, Director, IES Serge Bronkhorst, Bronkhorst International Law Services (BILS) / IES Jeannette E. Mullaart, Senior Fellow, IES Prof. Dr. Frans Nelissen, General Director, T.M.C. Asser Institute Dr. Wybe Th. Douma, Senior Researcher, European Law and International Trade Law, T.M.C. Asser Institute Leonardo Massai, Researcher, European Law, T.M.C. Asser Institute Marianna Kondas, Project Assistant, T.M.C. Asser Institute Daria Ratsiborinskaya, Project Assistant, T.M.C. Asser Institute Cover design: Géraud de Ville, IES Copyright © 2009 Institute for Environmental Security, The Hague, The Netherlands ISBN: ________________ NUR: ________________ All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this publication for education and other non- commercial purposes are authorised without any prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the authors and publisher are fully acknowledged. -

The International Law of War Crimes (Ll211)

THE INTERNATIONAL LAW OF WAR CRIMES (LL211) Course duration: 54 hours lecture and class time (Over three weeks) LSE Teaching Department: Department of Law Lead Faculty: Professor Gerry Simpson (Dept. of Law) Pre-requisites: Introduction to legal methods or equivalent. (Basic legal knowledge is a requirement. This would be satisfied by, among other things, Professor Lang’s LL105 course in the previous session). Introduction The following provides a course outline, list of lecture topics and sample readings. Use the list to familiarize yourself with the range and type of materials that will be used. Please note that the full reading lists and tutorial discussion questions will be provided at the start of the course. Welcome to this Summer School course in The International Law of War Crimes. The course will consist of twelve three-hour lectures and twelve one-and-a-half-hour classes. It will examine the law and policy issues relating to a number of key aspects of the information society. 1 The course examines, from a legal perspective, the rules, concepts, principles, institutional architecture, and enforcement of what we call international criminal law or international criminal justice, or, sometimes, the law of war crimes. The focus of the course is the area of international criminal law concerned with traditional “war crimes” and, in particular, four of the core crimes set out in the Rome Statute (war crimes, torture as a crime against humanity, genocide and aggression). It adopts an institutional (Nuremberg, Rwanda, the Former Yugoslavia), philosophical (Arendt, Shklar) and practical (the ICC) focus throughout. There will be a particular focus on war crimes trials and proceedings e.g. -

Methods of the International Criminal Court and the Role of Social Media

Methods of the International Criminal Court and the Role of Social Media Stefanie Kunze Northern Arizona University Flagstaff, AZ [email protected] April 2014 Introduction In the 20th century crimes against humanity and crimes of war have become more present in our conscience and awareness. The reasons are that they have become more methodical, more devastating, and also better documented. The 20th century has seen a development from international awareness of international crime and human rights violations, to the establishment of international criminal tribunals and ultimately the establishment of the International Criminal Court, and an undeniable influence of social media on the international discourse. Genocide is one of these crimes against humanity, and arguably the gravest one. With ad-hoc international and national criminal tribunals, special and hybrid courts, as well as the permanent International Criminal Court (ICC), big steps have been taken towards justice in the wake of genocide and crimes against humanity. Genocide is hardly a novel crime; it is the name that was newly coined in the mid-1900s. In fact, mass killings and possible genocide have occurred for centuries. The mass killing under Russian leader Stalin1 (Appendix A) occurred before the height of the Nazi Holocaust. Even before then, mass atrocities were committed over time, though not well documented. For instance the Armenian genocide under the Ottoman Empire, has been widely accepted as a “true” genocide, with roughly one-and-a-half-million dead.2 To this day Turkey denies these numbers.3 With the end of World War II and the end of the Nazi regime, the first international tribunals in history were held, prosecuting top-level perpetrators. -

Putin's Useful Idiots

Putin’s Useful Idiots: Britain’s Left, Right and Russia Russia Studies Centre Policy Paper No. 10 (2016) Dr Andrew Foxall The Henry Jackson Society October 2016 PUTIN’S USEFUL IDIOTS Executive Summary ñ Over the past five years, there has been a marked tendency for European populists, from both the left and the right of the political spectrum, to establish connections with Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Those on the right have done so because Putin is seen as standing up to the European Union and/or defending “traditional values” from the corrupting influence of liberalism. Those on the left have done so in part because their admiration for Russia survived the end of the Cold War and in part out of ideological folly: they see anybody who opposes Western imperialism as a strategic bedfellow. ñ In the UK, individuals, movements, and parties on both sides of the political spectrum have deepened ties with Russia. Some individuals have praised Putin and voiced their support for Russia’s actions in Ukraine; others have travelled to Moscow and elsewhere to participate in events organised by the Kremlin or Kremlin-backed organisations; yet more have appeared on Russia’s propaganda networks. Some movements have even aligned themselves with Kremlin-backed organisations in Russia who hold views diametrically opposed to their own; this is particularly the case for left-leaning organisations in the UK, which have established ties with far-right movements in Russia. ñ In an era when marginal individuals and parties in the UK are looking for greater influence and exposure, Russia makes for a frequent point of ideological convergence, and Putin makes for a deceptive and dangerous friend.