Irish Television Drama: a Society and Its Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rte Guide Tv Listings Ten

Rte guide tv listings ten Continue For the radio station RTS, watch Radio RTS 1. RTE1 redirects here. For sister service channel, see Irish television station This article needs additional quotes to check. Please help improve this article by adding quotes to reliable sources. Non-sources of materials can be challenged and removed. Найти источники: РТЗ Один - новости газеты книги ученый JSTOR (March 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) RTÉ One / RTÉ a hAonCountryIrelandBroadcast areaIreland & Northern IrelandWorldwide (online)SloganFuel Your Imagination Stay at home (during the Covid 19 pandemic)HeadquartersDonnybrook, DublinProgrammingLanguage(s)EnglishIrishIrish Sign LanguagePicture format1080i 16:9 (HDTV) (2013–) 576i 16:9 (SDTV) (2005–) 576i 4:3 (SDTV) (1961–2005)Timeshift serviceRTÉ One +1OwnershipOwnerRaidió Teilifís ÉireannKey peopleGeorge Dixon(Channel Controller)Sister channelsRTÉ2RTÉ News NowRTÉjrTRTÉHistoryLaunched31 December 1961Former namesTelefís Éireann (1961–1966) RTÉ (1966–1978) RTÉ 1 (1978–1995)LinksWebsitewww.rte.ie/tv/rteone.htmlAvailabilityTerrestrialSaorviewChannel 1 (HD)Channel 11 (+1)Freeview (Northern Ireland only)Channel 52CableVirgin Media IrelandChannel 101Channel 107 (+1)Channel 135 (HD)Virgin Media UK (Northern Ireland only)Channel 875SatelliteSaorsatChannel 1 (HD)Channel 11 (+1)Sky IrelandChannel 101 (SD/HD)Channel 201 (+1)Channel 801 (SD)Sky UK (Northern Ireland only)Channel 161IPTVEir TVChannel 101Channel 107 (+1)Channel 115 (HD)Streaming mediaVirgin TV AnywhereWatch liveAer TVWatch live (Ireland only)RTÉ PlayerWatch live (Ireland Only / Worldwide - depending on rights) RT'One (Irish : RTH hAon) is the main television channel of the Irish state broadcaster, Raidi'teilif's Siranne (RTW), and it is the most popular and most popular television channel in Ireland. It was launched as Telefes Siranne on December 31, 1961, it was renamed RTH in 1966, and it was renamed RTS 1 after the launch of RTW 2 in 1978. -

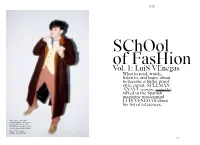

Luis Venegas What to Read, Watch, Listen To, and Know About to Become a Bullet-Proof Style Expert

KUltur kriTik SChOol of FasHion Vol. 1: LuiS VEnegas What to read, watch, listen to, and know about to become a bullet-proof style expert. SULEMAN ANAYA (username: vertiz136) talked to the Spanish magazine mastermind LUIS VENEGAS about his list of references. coat, jacket, and pants: Lanvin Homme, waistcoat: Polo Ralph Lauren, shirt: Dior Homme, bow tie: Marc Jacobs, shoes: Pierre Hardy photo: Chus Antón, styling: Ana Murillas 195 KUltur SChOol kriTik of FasHion At 31, Luis Venegas is already a one-man editorial powerhouse. He produces and publishes three magazines that, though they have small print runs, have a near-religious following: the six-year-old Fanzine 137 – a compendium of everything Venegas cares about, Electric Youth (EY!) Magateen – an oversized cornucopia of adolescent boyflesh started in 2008, and the high- ly lauded Candy – the first truly queer fashion magazine on the planet, which was launched last year. His all-encompassing, erudite view of the fashion universe is the foundation for Venegas’ next big project: the fashion academy he plans to start in 2011. It will be a place where people, as he says, “who are interested in fashion learn about certain key moments from history, film and pop culture.” To get a preview of the curriculum at Professor Venegas’ School of Fashion, Suleman Anaya paid Venegas a visit at his apartment in the Madrid neighborhood of Malasaña, a wonderful space that overflows with the collected objects of his boundless curiosity. Television ● Dynasty ● Dallas What are you watching these days in your scarce spare time? I am in the middle of a Dynasty marathon. -

£2.00 North West Mountain Rescue Team Intruder Alarms Portable Appliance Testing Approved Contractor Fixed Wire Testing

north west mountain rescue team ANNUAL REPORT 2013 REPORT ANNUAL Minimum Donation nwmrt £2.00 north west mountain rescue team Intruder Alarms Portable Appliance Testing Approved Contractor Fixed Wire Testing AA Electrical Services Domestic, Industrial & Agricultural Installation and Maintenance Phone: 028 2175 9797 Mobile: 07736127027 26b Carncoagh Road, Rathkenny, Ballymena, Co Antrim BT43 7LW 10% discount on presentation of this advert The three Tavnaghoney Cottages are situated in beautiful Glenaan in the Tavnaghoney heart of the Antrim Glens, with easy access to the Moyle Way, Antrim Hills Cottages & Causeway walking trails. Each cottage offers 4-star accommodation, sleeping seven people. Downstairs is a through lounge with open plan kitchen / dining, a double room (en-suite), a twin room and family bathroom. Upstairs has a triple room with en-suite. All cottages are wheelchair accessible. www.tavnaghoney.com 2 experience the magic of geological time travel www.marblearchcavesgeopark.com Telephone: +44 (0) 28 6634 8855 4 Contents 6-7 Foreword Acknowledgements by Davy Campbell, Team Leader Executive Editor 8-9 nwmrt - Who we are Graeme Stanbridge by Joe Dowdall, Operations Officer Editorial Team Louis Edmondson 10-11 Callout log - Mountain, Cave, Cliff and Sea Cliff Rescue Michael McConville Incidents 2013 Catherine Scott Catherine Tilbury 12-13 Community events Proof Reading Lowland Incidents Gillian Crawford 14-15 Search and Rescue Teams - Where we fit in Design Rachel Beckley 16-17 Operations - Five Days in March Photography by Graeme Stanbridge, Chairperson Paul McNicholl Anthony Murray Trevor Quinn 18-19 Snowbound by Archie Ralston President Rotary Club Carluke 20 Slemish Challenge 21 Belfast Hills Walk 23 Animal Rescue 25 Mountain Safety nwmrt would like to thank all our 28 Contact Details supporters, funders and sponsors, especially Sports Council NI 5 6 Foreword by Davy Campbell, Team Leader he north west mountain rescue team was established in Derry City in 1980 to provide a volunteer search and rescue Tservice for the north west of Northern Ireland. -

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

Irish Cultural Center of Cincinnati to Hold Green Tie Affair

Irish Cultural Center November 2013 of Cincinnati to Hold ianohio.com Green Tie Affair Saturday, November 2nd Saw Doctors Leo and Anto Hit the Road … page 2 Irish Cultural Center of Cincinnati Celebrates 4th Anniversary . page 6 Rattle of a Thompson Gun … page 7 Opportunity Ireland . page 9 Home to Mayo. pages 13 - 16 Big Screen to Broadway: Once Comes to Cleveland . page 19 Cover artwork by Cindy Matyi http://matyiart.com 2 IAN Ohio “We’ve Always Been Green!” www.ianohio.com November 2013 Saw Doctors Solo, Leo and Anto Hit the Road a little place back in Ireland where we together quite quickly. So we wanted it tested it out, and got a good response. to be different from anything we’d re- By Pete Roche, Special to the OhIAN of their stepping off the plane, and the And it looks like it worked. But we’ll be corded before. So we used the mandolin, guitarist sounded enthusiastic about tweaking it as we figure it out! which is a very different thing than what The North Coast’s music-loving Irish winding his way through the Midwest OhIAN: Apart from the music, how we’d done before with the Saw Doctors. contingent always turns out in strong in true troubadour fashion. will this tour be different from a Saw And I think that’s important. People are numbers whenever the rock quintet OhIAN: Hello again, Leo! Great to Doctors tour? saying to me it feels like they came to from the little Galway town of Tuam be catching up with you again! So you LEO: It’s going to be a whole new Ireland before we left it, because they’d play our neck of the woods. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

Malachy Conway (National Trust)

COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY IN NORTHERN IRELAND Community Archaeology in Northern Ireland Malachy Conway, Malachy Conway, TheArchaeological National Trust Conservation CBA Advisor Workshop, Leicester 12/09/09 A View of Belfast fromThe the National National Trust Trust, Northern property Ireland of Divis Re &g Thione Black Mountain Queen Anne House Dig, 2008 Castle Ward, Co. Down 1755 1813 The excavation was advertised as part of Archaeology Days in NI & through media and other publicity including production of fliers and banners and road signs. Resistivity Survey results showing house and other features Excavation aim to ’ground truth’ Prepared by Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork, QUB, 2007 the survey results through a series of test trenches, with support from NIEA, Built Heritage. Survey & Excavation 2008 Castle Ward, Co. Down All Photos by M. Conway (NT) Unless otherwise stated Excavation ran for 15 days (Wednesday-Sunday) in June 2008 and attracted 43 volunteers. The project was supported by NT archaeologist and 3 archaeologists from Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork (QUB), through funding by NIEA, Built Heritage. The volunteers were given on-site training in excavation and recording. Public access and tours were held throughout field work. The Downpatrick Branch of YAC was given a day on-site, where they excavated in separate trenches and were filmed and interview by local TV. Engagement & Research 2008 Public engagement Pointing the way to archaeology Castle Ward, Co. Down All Photos M. Conway (NT) Members of Downpatrick YAC on site YAC members setting up for TV interview! Engagement was one of the primary aims of this project, seeking to allow public to access and Take part in current archaeological fieldwork and research. -

Complaint, an Tost Fada (The Long Silence), Written and Narrated By

Four pages 1 Complaint, An Tost Fada (The Long Silence), written and narrated by Eoghan Harris, produced and directed by Gerry Gregg, Praxis Films, RTÉ One, 16 April 2012, 7.30pm From: Tom Cooper, 23 Delaford Lawn, Knocklyon, Dublin 16 Telephone: 085 7065200, Email: [email protected], 14 May 2012 (replaces 10 May complaint, please reply by email if possible) Eoghan Harris scripted and narrated an Irish language programme broadcast on RTÉ on 16 April 2012, produced and directed by Gerry Gregg, made by their company, Praxis Films. An Tost Fada (The Long Silence) told a compelling story of Rev’d George Salter’s father, William, being forced to abandon his West Cork farm in 1922. The story was personally moving but the telling of it was historically misleading. The subject matter of the programme concerns matters of public controversy and debate: (a) the specific killing of 13 Protestant civilians in Ballygroman, Dunmanway, in and around Ballineen- Enniskeane and Clonakilty, between 26-9 April 1922; (b) and, generally, the treatment of the Protestant minority in Southern Ireland. The programme makers broadcast incorrect information, seemingly so as to maintain the programme’s pre-selected narrative drive. It would appear, also, the programme makers did not avail of the services of a historical adviser. Had they done so, it might have prevented obvious errors. Here are some examples of the errors. THE SALTER FAMILY 1. The programme contained the following statement: ‘George’s father [William] had six sisters and two brothers. But every one of them left Ireland by April 1922. -

Horaires Des Projections Screening Times

HORAIRES DES PROJECTIONS SCREENING TIMES LE POCKET GUIDE 2016 A ÉTÉ PUBLIÉ AVEC DES INFORMATIONS REÇUES JUSQU'AU 29/04/2016 THE POCKET GUIDE 2016 HAS BEEN EDITED WITH INFORMATION RECEIVED UP UNTIL 29/04/2016 Toutes les projections du Marché sont accessibles sur présentation du badge Marché du Film ou invitation délivrée par le Service Projections. Les projections dans les salles Lumière, Debussy, Buñuel, Salle du Soixantième, Théâtre Croisette et Miramar sont accessibles sur présentation du badge Marché ou Festival. Access to Marché du Film screenings is upon presentation of the Marché badge or an invitation given by the Marché Screening Department. Access to screenings taking place in Lumière, Debussy, Buñuel, Salle du Soixantième, Théâtre Croisette and Miramar is upon presentation of either a Marché or Festival badge. CO: Official Competition • HC: Out of Competition • CC: Cannes Classics • CR: Un Certain Regard • BLUE TITLE : Film screened for the first time at a market QR: Directors Fortnight • SC: Semaine de la critique • press: Press allowed • invite only: By invitation only • priority only: Priority badges only SUNDAY 15 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 08:30 (125’) CO 15:30 (158’) CO 19:30 (125’) CO 22:30 (116’) HC LUMIÈRE FROM THE LAND OF THE MOON AMERICAN HONEY FROM THE LAND OF THE MOON THE NICE GUYS TICKET REQUIRED Nicole Garcia Andrea Arnold Nicole Garcia Shane Black 2 294 seats STUDIOCANAL PROTAGONIST PICTURES STUDIOCANAL BLOOM 11:30 (145’) CO 14:30 (162’) CO 17:30 (120’) HC 19:45 (106’) HC SALLE AGASSI, THE -

5 Day Western Ireland and Dublin Incentive Itinerary

SAMPLE PROGRAMME Ireland WEST & DUBLIN’S FAIR CITY 60 – 85 Guests 1 WHY IRELAND AND A TOUCH OF IRELAND? . “Just for fun” – Ireland has a special magic that starts working the minute you touchdown. Barriers are broken down with the emphasis on fun & the unique Irish experience . Painless travel – no special vaccinations needed – just a capacity to drink a few pints of Guinness! . Great programme mix – lively, cultural city action combined with the “hidden Ireland” – wild romantic nature WITHOUT long bus journeys! . Ireland never says “No” – we make things happen! . Excellent standard of hotels . A Touch of Ireland – Creative DMC & expert reliable Partner with multilingual staff – we understand the demands of the corporate client. 2 WEST IRELAND – LUXURY CASTLE ACCOMMODATION Ashford Castle 5* Cong, Co. Mayo www.ashford.ie Ashford Castle in the heart of the Connemara region, is just one and a half hours from Shannon airport, on the northern shores of Lough Corrib. The countryside around it provided the scenery for the John Wayne classic, “The Quiet Man”. Ashford Castle was selected as the best hotel in Ireland in the 1989 and 1990 Egon Ronay Guide. The original Castle dates back to the 13th century. It has been splendidly restored with rich panelling, intricately carved balustrades, suits of armour and masterpiece paintings. This year the hotel has undergone major refurbishment and is looking stunning. There are 83 rooms in total in the castle offering 5* luxury. Ashford boasts two gourmet restaurants; The “George V” dining room offers traditional and continental menus, while “The Connaught Room” specialises in acclaimed French cuisine. -

About the Artists

Fishamble: The New Play Company presents Swing Written by Steve Blount, Peter Daly, Gavin Kostick and Janet Moran Performed by Arthur Riordan and Gene Rooney ABOUT THE ARTISTS: Arthur Riordan - Performer (Joe): is a founder member of Rough Magic and has appeared in many of their productions, including Peer Gynt, Improbable Frequency, Solemn Mass for a Full Moon in Summer, and more. He has also worked with the Abbey & Peacock Theatre, Gaiety Theatre, Corcadorca, Pan Pan, Druid, The Corn Exchange, Bedrock Productions, Red Kettle, Fishamble, Project, Bewleys Café Theatre and most recently, with Livin’ Dred, in their production of The Kings Of The Kilburn High Road. Film and TV appearances include Out Of Here, Ripper Street, The Clinic, Fair City, Refuge, Borstal Boy, Rat, Pitch’n’Putt with Joyce’n’Beckett, My Dinner With Oswald, and more. Gene Rooney - Performer (May): has performed on almost every stage in Ireland in over 40 productions. Some of these include: Buck Jones and the Bodysnatchers (Dublin Theatre Festival), The Colleen Bawn Trials (Limerick City of Culture), Pigtown, The Taming of the Shrew, Lovers (Island Theatre Company), The Importance of Being Earnest (Gúna Nua), Our Father (With an F Productions), How I Learned to Drive (The Lyric, Belfast), I ❤Alice ❤ I (Hot for Theatre), TV and film work includes Moone Boy, Stella Days, The Sea, Hideaways, Killinaskully, Botched, The Last Furlong and The Clinic Janet Moran - Writer Janet’s stage work includes Juno and the Paycock (National Theatre, London/Abbey Theatre coproduction), Shibari, Translations, No Romance, The Recruiting Officer, The Cherry orchard, She Stoops to Conquer, Communion, The Barbaric Comedies, The Well of the Saints and The Hostage (all at the Abbey Theatre). -

Irish Political Review, October 2010

1640s Today Famine Or Holocaust? Fianna Fail Renaissance? John Minahane Jack Lane Labour Comment page 14 page 16 back page IRISH POLITICAL REVIEW October 2010 Vol.25, No.10 ISSN 0790-7672 and Northern Star incorporating Workers' Weekly Vol.24 No.10 ISSN 954-5891 What's Constitutional? Béal an Lenihan Junior Minister Mansergh Speaks So Brian Lenihan made the journey Fianna Fail Junior Minister Martin Mansergh has been putting himself about. from Cambridge University to Beal na Speaking at the McCluskey Summer School he said that Fianna Fail could not contest mBlath. It was a short trip. Now, if he had elections in the North because it was a party in government in the Republic and to do so gone to Kilcrumper! . would create a conflict of interest and damage the peace process. He hailed his appearance at the place Senior Fianna Fail Ministers, Dermot Ahern and Eamon Cuiv, have been encouraging where Michael Collins,master of the the setting up of Party organisations in the North. The measure is generally supported Treaty state, was killed in an absurd gesture by Cumainn around the South. The question of contesting elections in the North has not of bravado, as a "public act of historical arisen as a practical proposition because party organisation is still in a rudimentary stage. reconciliation". But Mansergh has jumped in to pre-empt it, supported by the new leader of the SDLP, This historical reconciliation was made Margaret Ritchie. The Irish News wrote: over sixty years ago, when those whom "Martin Mansergh's comments will come as a blow to party members lobbying for the Collins had left in the lurch made a final Republic's senior governing party to contest assembly elections next year.