Thirty Years Later: Remembering the U.S. Churchwomen in El Salvador and the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

March 12.Pub

March 12, 2006 Rev. Robert J. Schrader, Pastor Dear Parishioners, Rev. Robert T. Werth, Parochial Vicar Our Lenten Retreat began this past week, and I think everyone who attended will agree: it is just the spiritual medicine we all most Weekend Liturgy Schedule need to nurse us to the best possible spiritual health. “Spirituality” (a Saturday 4:30 p.m. St. James challenge in all of our lives, to be sure) is the theme of this year’s re- Sunday 8:00 a.m. St. James treat, and we were given much to ponder, indeed: “Spirituality is Sunday 9:00 a.m. St. John what we do with God’s fire in our life” and (from Joan Chittister) Sunday 9:45 a.m. St. Ambrose “Silence is that place just before the voice of God.” Our sharings at Sunday 11:00 a.m. St. John table were then very helpful as well, and the refreshments were abun- Sunday 5:00 p.m. St. Ambrose dant and superb. Our next session is tomorrow, Monday, 11:00 A.M.- 12:30 P.M. (bring brown bag lunch) OR 7:00-8:30 P.M. (refreshments Weekday Liturgy Schedule Monday 7:45 a.m. St. James follow both sessions). Even if you missed last week, there are still 4 Tuesday 9:15 a.m. St. Ambrose more sessions (last year’s retreat was 3 sessions total). Do join us if Wednesday 7:45 a.m. St. James you can for a Lenten experience that’s sure to inspire! 12:10 p.m. St. -

A History of Political Murder in Latin America Clear of Conflict, Children Anywhere, and the Elderly—All These Have Been Its Victims

Chapter 1 Targets and Victims His dance of death was famous. In 1463, Bernt Notke painted a life-sized, thirty-meter-long “Totentanz” that snaked around the chapel walls of the Marienkirche in Lübeck, the picturesque port town outside Hamburg in northern Germany. Individuals covering the entire medieval social spec- trum were represented, ranging from the Pope, the Emperor and Empress, and a King, followed by (among others) a duke, an abbot, a nobleman, a merchant, a maiden, a peasant, and even an infant. All danced reluctantly with grinning images of the reaper in his inexorable procession. Today only photos remain. Allied bombers destroyed the church during World War II. If Notke were somehow transported to Latin America five hundred years later to produce a new version, he would find no less diverse a group to portray: a popular politician, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, shot down on a main thoroughfare in Bogotá; a churchman, Archbishop Oscar Romero, murdered while celebrating mass in San Salvador; a revolutionary, Che Guevara, sum- marily executed after his surrender to the Bolivian army; journalists Rodolfo Walsh and Irma Flaquer, disappeared in Argentina and Guatemala; an activ- ist lawyer and nun, Digna Ochoa, murdered in her office for defending human rights in Mexico; a soldier, General Carlos Prats, murdered in exile for standing up for democratic government in Chile; a pioneering human rights organizer, Azucena Villaflor, disappeared from in front of her home in Buenos Aires never to be seen again. They could all dance together, these and many other messengers of change cut down by this modern plague. -

“Your Love and Your Grace. It Is All I Need.” Joan L. Roccasalvo, C.S.J. Week of November 16, 2017

“Your love and your grace. It is all I need.” Joan L. Roccasalvo, C.S.J. Week of November 16, 2017 How many times had they prayed in solitude and in public, “Give me your love and your grace. It is all I need?” A thousand times? In the end, they had no time to utter lengthy prayers, perhaps not even this final verse of St. Ignatius’ self-offering. Leisurely, they had prayed it for years. Now they were suddenly called on to live it in death. In the stealth of night, in those early hours of November 16th, 1989, six Jesuits were prodded from a deep sleep and dragged out of their beds to the grounds of their University of Central America. That moment had come when the prayer of self-giving would ask of them a final Yes. They were not entirely caught by surprise. Their residence had been visited a few days before. It was a warning as though to say: ‘Teach, but stay out of our business.’ Of all people, a young student of the Jesuit high school was enlisted to execute in cold blood six Jesuits, their cook and her daughter: Ignacio Ellacuría, the University Rector, an internationally known philosopher and tireless in his efforts to promote peace through his writings, conferences and travels abroad; . They also split open his head and spread his brains on the grass to make it clear why he had been killed. They certainly understood the symbolism of the head, the seat of the intellect. Segundo Montes. Head of the University of Central America sociology department, director of the new human rights institute, superior of the Jesuit community. -

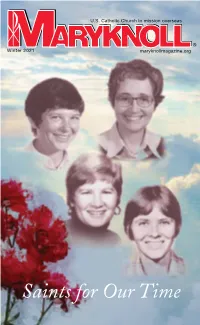

Saints for Our Time from the EDITOR FEATURED STORIES DEPARTMENTS

U.S. Catholic Church in mission overseas ® Winter 2021 maryknollmagazine.org Saints for Our Time FROM THE EDITOR FEATURED STORIES DEPARTMENTS n the centerspread of this issue of Maryknoll we quote Pope Francis’ latest encyclical, Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship, which Despite Restrictions of 2 From the Editor Iwas released shortly before we wrapped up this edition and sent it to the COVID-19, a New Priest Is 10 printer. The encyclical is an important document that focuses on the central Ordained at Maryknoll Photo Meditation by David R. Aquije 4 theme of this pontiff’s papacy: We are all brothers and sisters of the human family living on our common home, our beleaguered planet Earth. Displaced by War 8 Missioner Tales The joint leadership of the Maryknoll family, which includes priests, in South Sudan 18 brothers, sisters and lay people, issued a statement of resounding support by Michael Bassano, M.M. 16 Spirituality and agreement with the pope’s message, calling it a historic document on ‘Our People Have Already peace and dialogue that offers a vision for global healing from deep social 40 In Memoriam and economic divisions in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. “We embrace Canonized Them’ by Rhina Guidos 24 the pope’s call,” the statement says, “for all people of good will to commit to 48 Orbis Books the sense of belonging to a single human family and the dream of working together for justice and peace—a call that includes embracing diversity, A Listener and Healer 56 World Watch encounter, and dialogue, and rejecting war, nuclear weapons, and the death by Rick Dixon, MKLM 30 penalty.” 58 Partners in Mission This magazine issue is already filled with articles that clearly reflect the Finding Christmas very interconnected commonality that Pope Francis preaches, but please by Martin Shea, M.M. -

November 29 2020 Bulletin

† Pastor Fr. Ben Onegiu, A.J. † Parochial Vicar Fr. Felix Kauta, A.J. St. James Roman Catholic Parish † Deacons Dcn. Frank Devine A Faith and Family Community Dcn. Marvin Hernandez Dcn. Ron TenBarge 19640 N. 35th Avenue, Glendale, Arizona 85308 † Sisters in Residence Sr. Betty Banja, S.H.S. Phone 623-581-0707 † Fax 623-581-0110 ● Business Manager Bob Piotrowski Ext.101 www.stjames-greater.com Finance Assistant Kristy Hillhouse Administrative Assistant Terri Simonetta ● Director Liturgy & RE Sr. Sophie Lado, S.H.S Formation Assistant Mary Ann Zimmerman ● Director of Music James Poppleton Assistant Music Director Mike Giacalone ● Receptionists Gretchen Fenninger Kristy Hillhouse Irene Molette Terri Simonetta ● Facilities Coordinator Rene Vera Maintenance Martin Sanchez Vince Paul Matthew 13:33-37 • CTP Coordinator Christina Metelski • Funeral Coordinator Deacon Frank Devine “Be watchful! Be alert! • Bulletin Editor Thelia Morris You do not know when the time will come…” • St. Vincent DePaul Phone: 623-581-0728 • Holy Cross Catholic Phone: 623-936-1710 Cemetery & Funeral Home (Available 24 hours) Weekend Masses † Saturday - 4:00PM Sunday - 7:30AM - 8:00AM (Hall) - 9:00AM - 11:00AM Apostles of Jesus Mission Appeal (Spanish) - 11:15AM (Hall) Daily Mass † Wednesday - 7:00PM November 28th and November 29th Monday-Tuesday-Thursday-Friday-Saturday - 8:00AM Holy Days † Please consult the Parish Office Reconciliation † 2nd & 4th Wednesdays - 6:00PM-6:45PM Saturday - 2:00PM - 3:30PM, or by appointment Parish Office Hours † Sunday - 8:00AM-2:00PM / Monday- Thursday - 9:00AM-Noon 12:30PM-4PM / Friday - 9:00AM- Noon / Saturday - 2:00PM-5:30PM ST. JAMES ROMAN CATHOLIC PARISH WELCOME… We extend our hearts in a warm St. -

Index to the US Department of State Documents Collection, 2010

Description of document: Index to the US Department of State Documents Collection, 2010 Requested date: 13-May-2010 Released date: 03-December-2010 Posted date: 09-May-2011 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Officer Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL US Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Notes: This index lists documents the State Department has released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) The number in the right-most column on the released pages indicates the number of microfiche sheets available for each topic/request The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

(B) (6) 1 2 [Right Margin: J.S

f [Illegible stamp in right margin] EL SALVADOR: FROM THE GENOCIDE OF THE MILITARY JUNTA TO THE HOPE OF THE INSURRECTIONAL STRUGGLE [Stamp in right margin: University of(Illegible), El Salvador, C.A.] [Illegible stamp] [Emblem] LEGAL AID ARCHBISHOPRIC OF SAN SALVADOR R4957 NYC Translation #101587 (Spanish) (b) (6) 1 2 [Right margin: J.S. CAI'7,1ASUNIVERSITY, C1DAI, El Salvador, C.A.] INDEX Page INTRODUCTION 3 TYPICAL CASES OF THE PRACTICE OF GENOCIDE IN EL SALVADOR 5 I. POLITICAL ASSASSINATIONS AND PARTIES RESPONSIBLE 7 Presentation of significant eases 11 Evidence against the Government and FF.AA. of El Salvador 16 I[. DISAPPEARANCES/CAPTURES FOR POLITICAL REASONS 17 Ill. GENERAL REPRESSION 19 IV. PERSECUTION OF THE CHURCH 21 GENOCIDE AND WAR OF EXTERMINATION IN EL SALVADOR 31 I. BY WAY OF INTRODUCTION 33 If. GENOCIDE: THE SUBJECT THAT CONCERNS US 34 Ill, EXTERMINATION IN EL SALVADOR? 35 IV. ASPECTS OF INTENTIONALITY 39 V. BY WAY OF CONCLUSION 48 THE RIGHT TO EXERCISE LEGITIMATE DEFENSE: POPULAR INSUR- RECTION 51 I. BACKGROUND 53 II. IMPOSITION OF NAPOLEON DUARTE AND ABDUL GUTIERREZ 55 IIL APPEAL TO THE WORLD'S CHRISTIAN-DEMOCRATIC ORGANIZATIONS 56 1V. APPEAL TO THE WORLD'S GOVERNMENTS 57 V. APPEAL TO THE WORLD'S CHRISTIANS AND MEN OF GOOD WILL 57 PHOTOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE 59 R4958 NYC Translation #101587 (Spanish) (b) (6) 2 3 INTRODUCTION OPEN LETTER TO THE PROGRESSIVE MEN, PEOPLES AND GOVERNMENTS OF THE WORLD When we intend to express ourselves, we are always conditioned by the socio- historical reality in which we are immersed On this date of January 15, 1981, our reality is of war, with the threat - which is more than a shadow - of direct North American intervention. -

Junior High Church History, Chapter Review

Junior High Church History, Chapter Review Chapter 3 “Blessed Are the Persecuted” 1. ________ of the Church are those who witness to their faith in Christ by suffering death. a. The laity b. Members c. Priests d. Martyrs 2. The martyrs’ courage and heroism testified to their faith in the ________, their hope in the eternal life promised by Christ, and their love for Christ. a. Church’s ability to save them b. teachings of St. Paul c. Paschal Mystery d. love they had for others 3. As the early Church spread, ________ refused to offer sacrifice to the Roman gods. a. Israelites b. Gentiles c. Greeks d. Christians 4. The Christians’ “rebellious activity” led to ________. a. protests on the street b. positions in government for them c. persecutions d. acceptance 5. ________ refused to worship Roman gods and was put to death. a. John the Baptist b. Saint Ignatius of Antioch c. Mary, the Mother of Jesus d. Mary Magdalene 6. Roman imperial authorities believed that condemning Ignatius to death would ________ the faith of the Church in Antioch. a. strengthen b. weaken c. increase d. help 7. Saints Agatha, Agnes, and Lucy were ________ because of their faith in the Church. a. forgiven b. released c. kidnapped d. martyred 8. ________ was killed because he told the prefect of Rome that the poor were the “true treasures of the Church”. a. Saint Lawrence the Deacon b. The Pope c. Saint Stephen d. Jesus 9. ________ values, customs, and practices infiltrated the societies where the Church lived during the first centuries of the Church. -

Western Pennsylvaniaâ•Žs First Martyr: Father Gerard A. Donovan, M.M

4 Western Pennsylvania’s First Martyr: Father Gerard A. Donovan, M.M. Go forth, farewell for life, O dearest brothers; Proclaim afar the sweetest name of God. We meet again one day in heaven’s land of blessings. Farewell, brothers, farewell.” – Charles-François Gounod’s missionary hymn, refrain sung at the annual Maryknoll Departure Ceremony1 John C. Bates Western Pennsylvania was true missionary territory well into the 30 miles east of the city of Mukden (today, Shenyang),6 would 19th century. A small number of colonial Catholics who migrated serve as headquarters for this new mission. to the area after the British secured control from the French was later joined by German and Irish immigrants seeking freedom, Maryknoll would become, to many, the best-known Catholic land, and employment. Used to privation in the “old country,” missionary order in the United States. Its monthly, The Field Afar the new arrivals survived and thrived. Their children, typically (later renamed Maryknoll magazine), enjoyed a broad national raised in modest circumstances, were no less able to cope with readership. That magazine, missionary appeals at parishes, teaching the challenges occasioned by an industrializing society. Imbued sisters’ encouragement of mission-mindedness among students in with the faith of their parents, this next generation of young parochial schools, and newspaper and radio coverage of mission- men and women responded to appeals by the Catholic Church ary activities abroad served to encourage vocations among young to become missionaries and evangelize the Americans who sought to become mission- 7 parts of the world where the Gospel had aries. -

Annual PILGRIMAGE/RETREAT

TO CENTRAL AMERICA PILGRIMAGE/RETREAT Annual PO Box 302, Maryknoll, NY 10545-0302 Maryknoll, PO Box 302, Annual PILGRIMAGE/RETREAT Fr. David La Buda, M.M. TO CENTRAL AMERICA January 10-21, 2022 Fr. Robert Dueweke, OSA For more information, contact Kris East Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers P.O. Box 302 Maryknoll, NY 10545-0302 510-276-5021 [email protected] www.maryknollpilgrimage.org “The violence we preach is the Stamp Place violence of love” Here Bro. Octavio Duran Archbishop Oscar Romero PN 30975-21 Pilgrimage Retreat 2022.indd 1 5/4/21 3:42 PM A 10 DAY SPIRITUAL Witness statements FROM PREVIOUS JOURNEY FOR BISHOPS, PILGRIMAGE/RETREAT PARTICIPANTS PRIESTS, BROTHERS AND “I find it difficult to express in words PERMANENT DEACONS the impact that this pilgrimage/retreat of January 14th-25th, 2019 had on me. I felt alk in the footsteps of modern day connected to these inspirational martyrs Wmartyrs. Learn why these coura- in a way that could not have been possible geous women and men, caught up in situations without the personal testimonies of others of civil war in which the people they served and and our physical presences in the sites of the Catholic Church itself suffered persecution, their martyrdom. Am eternally grateful!” were able to give their lives as witnesses of Jesus Christ. “By far this was a blessed pilgrimage – better than Rome, Ireland, France.” We will visit the tomb of Saint Archbishop Romero and celebrate Mass at the altar where “My participation in the Maryknoll he was assassinated. We will also visit the site Pilgrimage/Retreat to Central America in El Salvador where Maryknoll Sisters Ita Ford, during January 2019 impressed on me the Maura Clarke, Ursuline Sister Dorothy Kazel power of the preached word of God.” Fr. -

Northwest Catholic Women's Convocation

Northwest Catholic Women’s Convocation IIi April 22-23, 2005 AUTHOR TITLE PUBL. YR SYNOPSIS Vivienne SM “The State, the Moro Greenwood Press 2001 This essay by Angeles is included in “Contributions to the Study of Popular Culture, #65: Angeles, Ph.D. National Liberation Front, Religious Fundamentalism in Developing Countries” by Santosh C. Saha. and Islamic Resurgence in the Philippines” Betsey Beckman, A Retreat With Our Lady, St. Anthony 1997 Co-authored with Nina O’Connor and J. Michael Sparough. M.M. Dominic & Ignatius: Praying Messenger Press With Our Bodies Full Body Blessing: St. Anthony 1992 A superb meditation work that can be used for individual and group praise and movement. Praying with Movement Messenger Press Frida Berrigan “Proud to be an American? Common May “The weapons industry- companies like Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon and Northrop Not While it Chooses Bombs Dreams 2, Grumman- are also pretty tone deaf. With the country on a permanent war footing, the sky is Over Bread.” NewsCenter 2003 literally the limit for America's second most heavily subsidized industry.” Read more of Frida’s numer commentaries and articles at www.AlterNet.org/authors/5482 and at www.jonahhouse.org/frida_index.htm . “Now you see, now you In these times Sept. “U.S. military researchers are hard at work developing directed-energy weapons that could be don’t: The Pentagon’s 29, used to destroy communication lines, power grids, or fuel dumps, or to zero in on part of a Blinding Lasers” 2002 vehicle, like the engine.” But are they safe for civilian populations? Mary Boys, SNJM, Has God Only One Blessing? Paulist Press 2000 This compelling book makes academic scholarship highly accessible.