“Your Love and Your Grace. It Is All I Need.” Joan L. Roccasalvo, C.S.J. Week of November 16, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 12.Pub

March 12, 2006 Rev. Robert J. Schrader, Pastor Dear Parishioners, Rev. Robert T. Werth, Parochial Vicar Our Lenten Retreat began this past week, and I think everyone who attended will agree: it is just the spiritual medicine we all most Weekend Liturgy Schedule need to nurse us to the best possible spiritual health. “Spirituality” (a Saturday 4:30 p.m. St. James challenge in all of our lives, to be sure) is the theme of this year’s re- Sunday 8:00 a.m. St. James treat, and we were given much to ponder, indeed: “Spirituality is Sunday 9:00 a.m. St. John what we do with God’s fire in our life” and (from Joan Chittister) Sunday 9:45 a.m. St. Ambrose “Silence is that place just before the voice of God.” Our sharings at Sunday 11:00 a.m. St. John table were then very helpful as well, and the refreshments were abun- Sunday 5:00 p.m. St. Ambrose dant and superb. Our next session is tomorrow, Monday, 11:00 A.M.- 12:30 P.M. (bring brown bag lunch) OR 7:00-8:30 P.M. (refreshments Weekday Liturgy Schedule Monday 7:45 a.m. St. James follow both sessions). Even if you missed last week, there are still 4 Tuesday 9:15 a.m. St. Ambrose more sessions (last year’s retreat was 3 sessions total). Do join us if Wednesday 7:45 a.m. St. James you can for a Lenten experience that’s sure to inspire! 12:10 p.m. St. -

A Prophet for All Ages

STJHUMRev Vol. 4-2 1 A Prophet for All Ages Charles Plock, C. M Charles Plock, C. M. is currently a chaplain at St. John’s University. For the past two years he has been translating the homilies of Archbishop Romero for the Archdiocese of San Salvador that is advocating the cause for the canonization of Romero. He worked in the Republic of Panama for ten years and at St. John the Baptist Parish in Brooklyn before beginning ministry at the university. Introduction During the past two years I have had the privilege of translating the Sunday homilies of Archbishop Oscar A. Romero, a charismatic figure in the history of the Church of Latin America, as well as the universal Church. As James R. Brockman stated in his book, Romero: This was a man who lived his life amid the poverty and injustice of Latin America. He became a priest before Vatican II and a bishop after Medellin. As archbishop of San Salvador, he became the leader of the Church in his native land. But as archbishop he also became a man of the poor, their advocate when they had no other voice to demand justice for them. He suffered and gave his life on their behalf.1 From a historical perspective, Romero was the Archbishop of San Salvador during a time when most of Latin America was guided by the United States’ Doctrine of National Security. As a result of this policy most of the nations in Latin America were ruled by military dictatorships that were backed by the United States government. -

A History of Political Murder in Latin America Clear of Conflict, Children Anywhere, and the Elderly—All These Have Been Its Victims

Chapter 1 Targets and Victims His dance of death was famous. In 1463, Bernt Notke painted a life-sized, thirty-meter-long “Totentanz” that snaked around the chapel walls of the Marienkirche in Lübeck, the picturesque port town outside Hamburg in northern Germany. Individuals covering the entire medieval social spec- trum were represented, ranging from the Pope, the Emperor and Empress, and a King, followed by (among others) a duke, an abbot, a nobleman, a merchant, a maiden, a peasant, and even an infant. All danced reluctantly with grinning images of the reaper in his inexorable procession. Today only photos remain. Allied bombers destroyed the church during World War II. If Notke were somehow transported to Latin America five hundred years later to produce a new version, he would find no less diverse a group to portray: a popular politician, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, shot down on a main thoroughfare in Bogotá; a churchman, Archbishop Oscar Romero, murdered while celebrating mass in San Salvador; a revolutionary, Che Guevara, sum- marily executed after his surrender to the Bolivian army; journalists Rodolfo Walsh and Irma Flaquer, disappeared in Argentina and Guatemala; an activ- ist lawyer and nun, Digna Ochoa, murdered in her office for defending human rights in Mexico; a soldier, General Carlos Prats, murdered in exile for standing up for democratic government in Chile; a pioneering human rights organizer, Azucena Villaflor, disappeared from in front of her home in Buenos Aires never to be seen again. They could all dance together, these and many other messengers of change cut down by this modern plague. -

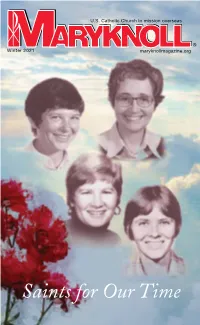

Saints for Our Time from the EDITOR FEATURED STORIES DEPARTMENTS

U.S. Catholic Church in mission overseas ® Winter 2021 maryknollmagazine.org Saints for Our Time FROM THE EDITOR FEATURED STORIES DEPARTMENTS n the centerspread of this issue of Maryknoll we quote Pope Francis’ latest encyclical, Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship, which Despite Restrictions of 2 From the Editor Iwas released shortly before we wrapped up this edition and sent it to the COVID-19, a New Priest Is 10 printer. The encyclical is an important document that focuses on the central Ordained at Maryknoll Photo Meditation by David R. Aquije 4 theme of this pontiff’s papacy: We are all brothers and sisters of the human family living on our common home, our beleaguered planet Earth. Displaced by War 8 Missioner Tales The joint leadership of the Maryknoll family, which includes priests, in South Sudan 18 brothers, sisters and lay people, issued a statement of resounding support by Michael Bassano, M.M. 16 Spirituality and agreement with the pope’s message, calling it a historic document on ‘Our People Have Already peace and dialogue that offers a vision for global healing from deep social 40 In Memoriam and economic divisions in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. “We embrace Canonized Them’ by Rhina Guidos 24 the pope’s call,” the statement says, “for all people of good will to commit to 48 Orbis Books the sense of belonging to a single human family and the dream of working together for justice and peace—a call that includes embracing diversity, A Listener and Healer 56 World Watch encounter, and dialogue, and rejecting war, nuclear weapons, and the death by Rick Dixon, MKLM 30 penalty.” 58 Partners in Mission This magazine issue is already filled with articles that clearly reflect the Finding Christmas very interconnected commonality that Pope Francis preaches, but please by Martin Shea, M.M. -

Un Testimonio Monseñor Oscar Arnulfo Romero Galdamez English

1 To Saint Romero of America To Márgara To my children To my grandchildren To my family, kin and friends alike Ever since the overwhelming news of Monsignor Romero‟s death – and having given thought to the incredible gift that the Lord bestowed upon me to be near a saint – I have not been able to calm my conscience for not writing about the moments I had the privilege to share with him. My wife, Márgara, and my children, Aída Verónica, Jorge José, Rebeca and Florence, were witnesses to many of these moments when Monsignor came to our home. When I remember Monsignor Romero, I have come to understand what it is like to live in sanctity, to practice humility and commitment, to convert to God every day and to do whatever He asked during the times when it was not clear what road the country should take. Monsignor Romero never aspired to become a prophet and mediator, as he indeed became; instead, his objective was to serve the Church and feel for its mission as the archbishop that he was. I have given testimony of my experience with Monsignor Romero in North Carolina, at the Riverside Church in New York City, at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, at La Trobe University in Australia and in New Zealand. But I did not keep records of these testimonies, given that I find it difficult to express myself in writing. Thanks to interviews by Héctor Lindo (2002) and Ricardo José Valencia (2005), of El Faro (2005), as well as the editing that Ana María Nafría undertook of these interviews and other conversations that expanded on some of the points, it is now possible to present my homage to the memory of Monsignor Óscar Arnulfo Romero. -

November 29 2020 Bulletin

† Pastor Fr. Ben Onegiu, A.J. † Parochial Vicar Fr. Felix Kauta, A.J. St. James Roman Catholic Parish † Deacons Dcn. Frank Devine A Faith and Family Community Dcn. Marvin Hernandez Dcn. Ron TenBarge 19640 N. 35th Avenue, Glendale, Arizona 85308 † Sisters in Residence Sr. Betty Banja, S.H.S. Phone 623-581-0707 † Fax 623-581-0110 ● Business Manager Bob Piotrowski Ext.101 www.stjames-greater.com Finance Assistant Kristy Hillhouse Administrative Assistant Terri Simonetta ● Director Liturgy & RE Sr. Sophie Lado, S.H.S Formation Assistant Mary Ann Zimmerman ● Director of Music James Poppleton Assistant Music Director Mike Giacalone ● Receptionists Gretchen Fenninger Kristy Hillhouse Irene Molette Terri Simonetta ● Facilities Coordinator Rene Vera Maintenance Martin Sanchez Vince Paul Matthew 13:33-37 • CTP Coordinator Christina Metelski • Funeral Coordinator Deacon Frank Devine “Be watchful! Be alert! • Bulletin Editor Thelia Morris You do not know when the time will come…” • St. Vincent DePaul Phone: 623-581-0728 • Holy Cross Catholic Phone: 623-936-1710 Cemetery & Funeral Home (Available 24 hours) Weekend Masses † Saturday - 4:00PM Sunday - 7:30AM - 8:00AM (Hall) - 9:00AM - 11:00AM Apostles of Jesus Mission Appeal (Spanish) - 11:15AM (Hall) Daily Mass † Wednesday - 7:00PM November 28th and November 29th Monday-Tuesday-Thursday-Friday-Saturday - 8:00AM Holy Days † Please consult the Parish Office Reconciliation † 2nd & 4th Wednesdays - 6:00PM-6:45PM Saturday - 2:00PM - 3:30PM, or by appointment Parish Office Hours † Sunday - 8:00AM-2:00PM / Monday- Thursday - 9:00AM-Noon 12:30PM-4PM / Friday - 9:00AM- Noon / Saturday - 2:00PM-5:30PM ST. JAMES ROMAN CATHOLIC PARISH WELCOME… We extend our hearts in a warm St. -

Index to the US Department of State Documents Collection, 2010

Description of document: Index to the US Department of State Documents Collection, 2010 Requested date: 13-May-2010 Released date: 03-December-2010 Posted date: 09-May-2011 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Officer Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL US Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Notes: This index lists documents the State Department has released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) The number in the right-most column on the released pages indicates the number of microfiche sheets available for each topic/request The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

¡A Todos Ellos Gracias!

BOLETÍN N° 17 • AÑO • 26 JULIO 2020 De izq. a der.: los obispos Jorge de Viteri y Ungo, Tomás Miguel Pineda y Saldaña, y José Luis Cárcamo y Rodríguez. Le siguen los Arzobispos Antonio Adolfo Pérez y Aguilar, José Alfonso Belloso y Sánchez, Mons. Luis Chávez y González, San Oscar Arnulfo Romero Galdámez, junto a Mons. Arturo Rivera y Damas, S.D.B. Por úlitmo Mons. Fernando Sáenz Lacalle y Mons. José Luis Escobar Alas ¡A todos ellos gracias! En este próximo contexto, de las fiestas en honor al Divino Salvador del Mundo, patrono del país, traemos a cuenta esa constelación de obispos que han testimoniado, hasta el día de hoy el su amor al Pueblo de Dios, su fidelidad a la Iglesia Católica, y su fe en Cristo Jesús, Nuestro Salvador. La erección de la Provincia eclesiástica de El Salvador religiosa que ocasionó un doloroso enfrentamiento de la (...) acaeció el 11 de febrero de 1913 e implica dos cambios Iglesia católica con el Estado salvadoreño. Cosa sabida es importantes en la estructura del servicio que la Iglesia Católica de todos que la Asamblea Constituyente de ese tiempo presta a los salvadoreños. Primero, fueron erigidas dos nuevas nombró al presbítero y doctor José Matías Delgado, diócesis: una en el occidente del país, Santa Ana; y otra en el primer obispo de San Salvador; designación que la Santa oriente, San Miguel, con sus respectivos obispos. En segundo Sede Apostólica desconoció, y no solo, sino que condenó lugar, la diócesis más antigua, San Salvador, fue ascendida al como un abuso de poder. -

(B) (6) 1 2 [Right Margin: J.S

f [Illegible stamp in right margin] EL SALVADOR: FROM THE GENOCIDE OF THE MILITARY JUNTA TO THE HOPE OF THE INSURRECTIONAL STRUGGLE [Stamp in right margin: University of(Illegible), El Salvador, C.A.] [Illegible stamp] [Emblem] LEGAL AID ARCHBISHOPRIC OF SAN SALVADOR R4957 NYC Translation #101587 (Spanish) (b) (6) 1 2 [Right margin: J.S. CAI'7,1ASUNIVERSITY, C1DAI, El Salvador, C.A.] INDEX Page INTRODUCTION 3 TYPICAL CASES OF THE PRACTICE OF GENOCIDE IN EL SALVADOR 5 I. POLITICAL ASSASSINATIONS AND PARTIES RESPONSIBLE 7 Presentation of significant eases 11 Evidence against the Government and FF.AA. of El Salvador 16 I[. DISAPPEARANCES/CAPTURES FOR POLITICAL REASONS 17 Ill. GENERAL REPRESSION 19 IV. PERSECUTION OF THE CHURCH 21 GENOCIDE AND WAR OF EXTERMINATION IN EL SALVADOR 31 I. BY WAY OF INTRODUCTION 33 If. GENOCIDE: THE SUBJECT THAT CONCERNS US 34 Ill, EXTERMINATION IN EL SALVADOR? 35 IV. ASPECTS OF INTENTIONALITY 39 V. BY WAY OF CONCLUSION 48 THE RIGHT TO EXERCISE LEGITIMATE DEFENSE: POPULAR INSUR- RECTION 51 I. BACKGROUND 53 II. IMPOSITION OF NAPOLEON DUARTE AND ABDUL GUTIERREZ 55 IIL APPEAL TO THE WORLD'S CHRISTIAN-DEMOCRATIC ORGANIZATIONS 56 1V. APPEAL TO THE WORLD'S GOVERNMENTS 57 V. APPEAL TO THE WORLD'S CHRISTIANS AND MEN OF GOOD WILL 57 PHOTOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE 59 R4958 NYC Translation #101587 (Spanish) (b) (6) 2 3 INTRODUCTION OPEN LETTER TO THE PROGRESSIVE MEN, PEOPLES AND GOVERNMENTS OF THE WORLD When we intend to express ourselves, we are always conditioned by the socio- historical reality in which we are immersed On this date of January 15, 1981, our reality is of war, with the threat - which is more than a shadow - of direct North American intervention. -

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS Butchered)

674 5, 1987 CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS butchered). In the final stages of the syndrome the pa- he following exchangetook place at President tient starts to make excuses for the U.S. Administration Napole6n Duarte’s press conference here on Oc- that even the Administration is too shy to offer. tober 29, three days after the murder of Herbert Before the flag-kissing photo opportunity Duarte had ac- TErnesto Anaya, who headed the unofficial Salva- cused the Sandinista government of being responsible for doran Human Rights Commission: the civil war in El Salvador, a claim that no Washington hawk has had the face to make. He has stated publicly that wlll he was quite unaware of the use of Ilopango Air Force Base to of for the illegal supply of forces. Ilopango is about of of In twenty minutes by car from the center of San Salvador and is the headquarters of the Salvadoran Air Force. If Duarte 1s did not know that it was being used to attack Nicaragua, 1 to then he has effectively ceded power to an arrogant foreign to m~nlmum of You patron. he did know, while affirming the contrary and of while arguing that the flow of arms was in the other direc- of tion, then he has effectively ceded power to an arrogant U.S. not if foreign patron. In true Sadat style, Duarte has also “written” a book, of titled My This volume was co-authored by Diana Page and published onlyin English. It is dedicated to, One could make a number of observations about this among others, the Boy Scout movement (a large statue to reply. -

A Mass in Celebration of the Beatification of Fr. Michael

A Mass in Celebration of the Beatification of Fr. Michael McGivney, Diocesan Priest and Founder of the Knights of Columbus Saturday of the 30th Week of Ordinary Time Homily of Bishop John O. Barres Diocese of Rockville Centre St. Mary’s Church, New Haven, CT October 31, 2020 Holy priests have shaped the history of the United States. Their heroism, evangelizing zeal, and pastoral charity are woven into our nation’s story. Looking to those priest Saints and Blesseds who labored in this part of God’s vineyard that is the land of the free and the home of the brave, we see a wide and beautiful American kaleidoscope of “holiness and mission” in the Catholic priesthood. Think of the New York Jesuit martyrs: Saints Isaac Jogues (1607-1646), Rene Goupil (1608-1642), and Jean de Lalande (d. 1646). Recall the Redemptorist Saint John Neumann (1811-1860), the Bishop of Philadelphia, and his confrere, Blessed Francis Xavier Seelos (1819-1867). See the missionary hearts of Saint Juniper Serra (1713-1784) in California and Saint Damien of Molokai (1840-1889) in Hawaii. Call to mind the Capuchin Blessed Solanus Casey (1870-1957), a mystical porter who opened the Doors of Christ to so many souls. 2 Think, too, of Blessed Stanley Rother (1935-1981), a parish priest-missionary from Oklahoma who died as a parish priest-martyr in Guatemala. Spanning centuries, their priestly holiness has animated the life of the Church and contributed to our growth as one nation under God. -- Thanks be to God, today, October 31, 2020, this illustrious list of priest Saints and Blesseds has been increased with the Beatification of Father Michael J. -

Junior High Church History, Chapter Review

Junior High Church History, Chapter Review Chapter 3 “Blessed Are the Persecuted” 1. ________ of the Church are those who witness to their faith in Christ by suffering death. a. The laity b. Members c. Priests d. Martyrs 2. The martyrs’ courage and heroism testified to their faith in the ________, their hope in the eternal life promised by Christ, and their love for Christ. a. Church’s ability to save them b. teachings of St. Paul c. Paschal Mystery d. love they had for others 3. As the early Church spread, ________ refused to offer sacrifice to the Roman gods. a. Israelites b. Gentiles c. Greeks d. Christians 4. The Christians’ “rebellious activity” led to ________. a. protests on the street b. positions in government for them c. persecutions d. acceptance 5. ________ refused to worship Roman gods and was put to death. a. John the Baptist b. Saint Ignatius of Antioch c. Mary, the Mother of Jesus d. Mary Magdalene 6. Roman imperial authorities believed that condemning Ignatius to death would ________ the faith of the Church in Antioch. a. strengthen b. weaken c. increase d. help 7. Saints Agatha, Agnes, and Lucy were ________ because of their faith in the Church. a. forgiven b. released c. kidnapped d. martyred 8. ________ was killed because he told the prefect of Rome that the poor were the “true treasures of the Church”. a. Saint Lawrence the Deacon b. The Pope c. Saint Stephen d. Jesus 9. ________ values, customs, and practices infiltrated the societies where the Church lived during the first centuries of the Church.