ALEXANDER III the Men Who Roa4e GREAT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giresun, Ordu Ve Samsun Illerinde Findik Bahçelerinde Zarar Yapan Yaziciböcek (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) Türleri, Kisa Biyolojileri Ve Bulunuş Oranlari

OMÜ Zir. Fak. Dergisi, 2005,20(2):37-44 J. of Fac. of Agric., OMU, 2005,20(2):37-44 GİRESUN, ORDU VE SAMSUN İLLERİNDE FINDIK BAHÇELERİNDE ZARAR YAPAN YAZICIBÖCEK (COLEOPTERA: SCOLYTIDAE) TÜRLERİ, KISA BİYOLOJİLERİ VE BULUNUŞ ORANLARI Kibar AK Karadeniz Tarımsal Araştırma Enstitüsü, Samsun Meryem UYSAL S.Ü. Ziraat Fakültesi, Bitki Koruma Bölümü, Konya Celal TUNCER O.M.Ü. Ziraat Fakültesi, Bitki Koruma Bölümü, Samsun Geliş Tarihi: 09.12.2004 ÖZET: Bu çalışma fındık üretiminin yoğun olarak yapıldığı Giresun, Ordu ve Samsun illerinde fındık bahçelerinde son yıllarda giderek zararı artan yazıcıböcek (Col.: Scolytidae) türlerinin tespiti ve önemli türlerin kısa biyolojileri ve bulunuş oranlarının belirlenmesi amacıyla 2003 ve 2004 yıllarında yapılmıştır. Sürvey sahasında fındıklarda zararlı dört scolytid türü [ Xyleborus dispar (Fabricius), Lymantor coryli (Perris), Xyleborus xylographus (Say) ve Hypothenemus eruditus Westwood ] belirlenmiştir. Bu türlerden H. eruditus Türkiye’de fındıkta ilk kayıt niteliğindedir. L. coryli ve X. dispar en yaygın ve önemli türler olarak belirlenmiştir. Sürvey sahasındaki scolytid populasyonunun %90’ını L. coryli, %10’unu ise X. dispar oluşturmuştur. L. coryli’nin fındık alanlarında önemli bir zararlı olduğu bu çalışmayla ortaya konulmuş, ayrıca biyolojileriyle ilgili ilginç bulgular elde edilmiştir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Yazıcıböcekler, Scolytidae, Xyleborus dispar, Lymantor coryli, Xyleborus xylographus, Hypothenemus eruditus, Fındık BARK BEETLE (COLEOPTERA: SCOLYTIDAE) SPECIES WHICH ARE HARMFUL IN HAZELNUT ORCHARDS, THEIR SHORT BIOLOGY AND DENSITIES IN GIRESUN, ORDU AND SAMSUN PROVINCES OF TURKEY ABSTRACT: This study was carried out in 2003-2004 years to determine the species of Bark Beetle (Col.:Scolytidae), the densities and short biology of important species, which their importance has increased in the recent years in the hazelnut orchards of Giresun, Ordu and Samsun provinces where hazelnut has been intensively produced. -

The Charm of the Amalfi Coast

SMALL GROUP Ma xi mum of LAND 28 Travele rs JO URNEY Sorrento The Charm of the Amalfi Coast Inspiring Moments >Travel the fabled ribbon of the Amalfi Coast, a mélange of ice-cream colored facades, rocky cliffs and sparkling sea. >Journey to Positano, a picturesque INCLUDED FEATURES gem along the Divine Coast. Accommodations Itinerary >Relax amid gentle, lemon-scented (with baggage handling) Day 1 Depart gateway city A breezes in beautiful Sorrento. – 7 nights in Sorrento, Italy, at the Day 2 Arrive in Naples | Transfer A >Walk a storied path through the ruins first-class Hotel Plaza Sorrento. to Sorrento of Herculaneum and Pompeii. Day 3 Positano | Amalfi Extensive Meal Program >Discover fascinating history at a world- – 7 breakfasts, 3 lunches and 4 dinners, Day 4 Paestum renowned archaeological including Welcome and Farewell Day 5 Naples museum in Naples. Dinners; tea or coffee with all meals, Day 6 Sorrento plus wine with dinner. >From N eapolitan pizza to savory olive Day 7 Pompeii | Herculaneum oils to sweet gelato , delight in – Opportunities to sample authentic Day 8 Sorrento cuisine and local flavors. sensational regional flavors. Day 9 Transfer to Naples airport and >Experience four UNESCO World depart for gateway city A Your One-of-a-Kind Journey Heritage sites. – Discovery excursions highlight ATransfers and flights included for AHI FlexAir participants. the local culture, heritage and history. Paestum Note: Itinerary may change due to local conditions. – Expert-led Enrichment programs Walking is required on many excursions. enhance your insight into the region. – AHI Connects: Local immersion. – Free time to pursue your own interests. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Tomasz Grabowski Jagiellonian University, Kraków*

ELECTRUM * Vol. 21 (2014): 21–41 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.14.001.2778 www.ejournals.eu/electrum THE CULT OF THE PTOLEMIES IN THE AEGEAN IN THE 3RD CENTURY BC Tomasz Grabowski Jagiellonian University, Kraków* Abstract: The cult of the Ptolemies spread in various ways. Apart from the Lagids, the initiative came from poleis themselves; private cult was also very important. The ruler cult, both that organ- ised directly by the Ptolemaic authorities and that established by poleis, was tangibly benefi cial for the Ptolemaic foreign policy. The dynastic cult became one of the basic instruments of political activity in the region, alongside acts of euergetism. It seems that Ptolemy II played the biggest role in introducing the ruler cult as a foreign policy measure. He was probably responsible for bringing his father’s nickname Soter to prominence. He also played the decisive role in popularising the cult of Arsinoe II, emphasising her role as protector of sailors and guarantor of the monarchy’s prosperity and linking her to cults accentuating the warrior nature of female deities. Ptolemy II also used dynastic festivals as vehicles of dynastic propaganda and ideology and a means to popu- larise the cult. The ruler cult became one of the means of communication between the subordinate cities and the Ptolemies. It also turned out to be an important platform in contacts with the poleis which were loosely or not at all subjugated by the Lagids. The establishment of divine honours for the Ptolemies by a polis facilitated closer relations and created a friendly atmosphere and a certain emotional bond. -

The Influence of Achaemenid Persia on Fourth-Century and Early Hellenistic Greek Tyranny

THE INFLUENCE OF ACHAEMENID PERSIA ON FOURTH-CENTURY AND EARLY HELLENISTIC GREEK TYRANNY Miles Lester-Pearson A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11826 This item is protected by original copyright The influence of Achaemenid Persia on fourth-century and early Hellenistic Greek tyranny Miles Lester-Pearson This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews Submitted February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Miles Lester-Pearson, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2015. Date: Signature of Candidate: 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

PL. LXI.J the Position of Polykleitos in the History of Greek

A TERRA-COTTA DIADUMENOS. 243 A TERRA-COTTA DIADUMENOS. [PL. LXI.J THE position of Polykleitos in the history of Greek sculpture is peculiarly tantalizing. We seem to know a good deal about his work. We know his statue of a Doryphoros from the marble copy of it in Naples, and we know his Diadumenos from two marble copies in the British Museum. Yet with these and other sources of knowledge, it happens that when we desire to get closer to his real style and to define it there occurs a void. So to speak, a bridge is wanting at the end of an otherwise agreeable journey, and we welcome the best help that comes to hand. There is, I think, some such help to be obtained from the terra-cotta statuette recently acquired in Smyrna by Mr. W. R. Paton. But first it may be of use to recall the reasons why the marble statues just mentioned must fail to convey a perfectly true notion of originals which we are justified in assuming were of bronze. In each of these statues the artist has been compelled by the nature of the material to introduce a massive support in the shape of a tree stem. That is at once a new element in the design, and, as a distinguished French sculptor1 has rightly observed, this new element called for a modification of the entire figure. This would have been true of a marble copy made even 1 M. Eugene Guillaume, in Eayet's dell' Tnst. Arch, 1878, p. 5. He gives Monuments de VArt Antique, pt. -

CLASSICAL TURKEY Archaeology and Mythology of Asia Minor Wednesday, June 12Th - Wednesday, June 26Th (14 Nights, 15 Days)

CLASSICAL TURKEY Archaeology and Mythology of Asia Minor Wednesday, June 12th - Wednesday, June 26th (14 Nights, 15 Days) On this trip guests are guided through an in-depth examination of the Greco-Roman civilization in Western Asia Minor. The Aeolian and Ionian cities along the west coast of Anatolia were founded around 1000 B.C. while the Eastern Greek world made its first cultural gains at the beginning of the 7th century BC. We see first hand that Eastern Greek art and culture owe a considerable debt to their long-standing contact with the indigenous Lydian, Lycian and Carian cultures in Anatolia, not forgetting the Phrygians. The Ionian civilization was thus a product of the co-existence of Greeks with the natives of Asia Minor. The voyage of Jason and the Argonauts, legend of the Hellespont, the Iliad of Homer, Alexander the Great’s pilgrimage to Troy, Cleanthes of Assos, the Library of Pergamum, the legend of Asclepius, Coinage & Customs of the Lydians, the wealth of Croesus, the Temple of Diana, and the Oracle at Didyma will assist us in comprehending the creativity and inspiration of the period. Day 1 Istanbul Special category (4-star) hotel Guests are met by the tour director at the Atatürk Airport and are then taken to the hotel and assisted through check-in. Group participants meet each other and staff with a welcome drink before sitting down to dinner. (D) Day 2 Istanbul Special category (4-star) hotel This morning we visit the Istanbul Archaeology Museum (main building). The facade of the building was inspired by the Alexander Sarcophagus and Sarcophagus of the Mourning Women, both housed inside the Museum. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

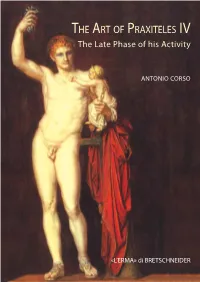

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

The Coins from the Necropolis "Metlata" Near the Village of Rupite

margarita ANDONOVA the coins from the necropolis "metlata" near the village of rupite... THE COINS FROM THE NECROPOLIS METLATA NEAR THE VILLAGE "OF RUPITE" (F. MULETAROVO), MUNICIPALITY OF PETRICH by Margarita ANDONOVA, Regional Museum of History– Blagoevgrad This article sets to describe and introduce known as Charon's fee was registered through the in scholarly debate the numismatic data findspots of the coins on the skeleton; specifically, generated during the 1985-1988 archaeological these coins were found near the head, the pelvis, excavations at one of the necropoleis situated in the left arm and the legs. In cremations in situ, the locality "Metlata" near the village of Rupite. coins were placed either inside the grave or in The necropolis belongs to the long-known urns made of stone or clay, as well as in bowls "urban settlement" situated on the southern placed next to them. It is noteworthy that out of slopes of Kozhuh hill, at the confluence of 167 graves, coins were registered only in 52, thus the Strumeshnitsa and Struma Rivers, and accounting for less than 50%. The absence of now identified with Heraclea Sintica. The coins in some graves can probably be attributed archaeological excavations were conducted by to the fact that "in Greek society, there was no Yulia Bozhinova from the Regional Museum of established dogma about the way in which the History, Blagoevgrad. souls of the dead travelled to the realm of Hades" The graves number 167 and are located (Зубарь 1982, 108). According to written sources, within an area of 750 m². Coins were found mainly Euripides, it is clear that the deceased in 52 graves, both Hellenistic and Roman, may be accompanied to the underworld not only and 10 coins originate from areas (squares) by Charon, but also by Hermes or Thanatos. -

Greece & Italy

First Class 15 Day Tour/Cruise Package Greece & Italy Day 1: Depart USA tions of the major streets in this ancient city including the Agora, Overnight flight to Athens. the Odeon, the Library, the marble-paved main Street, the Baths, Trajan’s Fountain, the Residences of the Patricians, the Pryta - Day 2: Arrive Athens neum, and Temple of Hadrian. The Great Theatre, built in the 4th We fly to Athens and check into our hotel. You will have the re - century B.C., could accommodate 24,000 spectators and it is fa - mainder of the day free to relax or take a stroll along the streets of mous even nowadays for its acoustics. This afternoon we visit the Athens to enjoy the flavor of the city. (B, D) Isle of Patmos, under statutory protection as a historic monu - ment. Here we have a tour to see the fortified monastery of St. Day 3: Cruising Mykonos John and the cave claimed to be where John received the Revela - We sail this morning from Athens to the quaint isle of Mykonos, tion. Back on the ship, enjoy the Captain's dinner before settling called the island of windmills. Experience the waterfront lined in to your cabin for the night. with shops and cafes and then stroll the charming walkways through a maze of whitewashed buildings before returning to the Day 5: Crete and Santorini ship for dinner and evening entertainment. (B, D) Crete is the largest and the most rugged of the Greek islands. Take a tour to Heraklion and the fantastic ruins of the Palace of Knos - Day 4: Ephesus and Patmos sos. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1.