Title 英文目次ほか Author(S) Citation 京都帝国大学文学部考古学研究報告

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PICTORIAL POSTCARDS of a COLONIAL CITY: the "DREAM- WORK" of JAPANESE IMPERIAL- ISM Won Gi Jung

Won Gi Jung 39 PICTORIAL POSTCARDS OF A COLONIAL CITY: THE "DREAM- WORK" OF JAPANESE IMPERIAL- ISM Won Gi Jung Introduction by Yumi Moon, Associate Professor of His- tory, Stanford University The Japanese empire produced many kinds of visual sources in governing its colonies. Won Gi Jung focuses on postcards of colonial Korea collected in the LUNA Archive of the University of Chicago, analyzing their pictorial narratives and the contexts in which they were made and consumed. Comparing Japan’s case with Western colonialism, Won Gi associates the fourishing postcard industry with the development of modern tourism in the Japanese metropole. He also accentuates Japan’s interest in using foreign tourism to present positive images of its empire to the world. For this reason it was the colonial state of Korea, rather than private studios, that produced the postcards, carefully curating the images of main tourist sites in Keijō (present-day Seoul) and elsewhere. Won Gi also discusses several publications by Western tourists who visited colonial Korea and offers a balanced commen- tary on the colonial state’s “dreamlike” representation of Keijō. Pictorial Postcards 40 Pictorial Postcards of a Colonial City: The "dreamwork" of Japanese Imperialism Won Gi Jung It’s because she found only one or two ‘Korean-made’ products… The [Australian] mistress wanted to purchase Joseon costume for female, but she couldn’t fnd any ready-made clothes. She said, “How come I cannot fnd even one pictorial postcard made by Koreans?”1 Blooming cherry blossom trees adorn the streets of spring- time Keijo.2 A Shinto shrine, dedicated to the Japanese sun-god- dess Amaterasu, stands with dignity at the center of the city.3 Street signs and brochures written in Japanese fll a crowded market- place.4 Tourists saw these landscapes in pictorial postcards sold at train stations, private studios, or near historical sites in colonial Korea. -

The Making of Modern Japan

The Making of Modern Japan The MAKING of MODERN JAPAN Marius B. Jansen the belknap press of harvard university press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 2000 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Third printing, 2002 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2002 Book design by Marianne Perlak Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jansen, Marius B. The making of modern Japan / Marius B. Jansen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-674-00334-9 (cloth) isbn 0-674-00991-6 (pbk.) 1. Japan—History—Tokugawa period, 1600–1868. 2. Japan—History—Meiji period, 1868– I. Title. ds871.j35 2000 952′.025—dc21 00-041352 CONTENTS Preface xiii Acknowledgments xvii Note on Names and Romanization xviii 1. SEKIGAHARA 1 1. The Sengoku Background 2 2. The New Sengoku Daimyo 8 3. The Unifiers: Oda Nobunaga 11 4. Toyotomi Hideyoshi 17 5. Azuchi-Momoyama Culture 24 6. The Spoils of Sekigahara: Tokugawa Ieyasu 29 2. THE TOKUGAWA STATE 32 1. Taking Control 33 2. Ranking the Daimyo 37 3. The Structure of the Tokugawa Bakufu 43 4. The Domains (han) 49 5. Center and Periphery: Bakufu-Han Relations 54 6. The Tokugawa “State” 60 3. FOREIGN RELATIONS 63 1. The Setting 64 2. Relations with Korea 68 3. The Countries of the West 72 4. To the Seclusion Decrees 75 5. The Dutch at Nagasaki 80 6. Relations with China 85 7. The Question of the “Closed Country” 91 vi Contents 4. STATUS GROUPS 96 1. The Imperial Court 97 2. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

Copyrighted Material

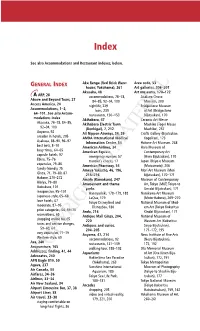

18_543229 bindex.qxd 5/18/04 10:06 AM Page 295 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Aka Renga (Red Brick Ware- Area code, 53 house; Yokohama), 261 Art galleries, 206–207 Akasaka, 48 Art museums, 170–172 A ARP, 28 accommodations, 76–78, Asakura Choso Above and Beyond Tours, 27 84–85, 92–94, 100 Museum, 200 Access America, 24 nightlife, 229 Bridgestone Museum Accommodations, 1–2, bars, 239 of Art (Bridgestone 64–101. See also Accom- restaurants, 150–153 Bijutsukan), 170 modations Index Akihabara, 47 Ceramic Art Messe Akasaka, 76–78, 84–85, Akihabara Electric Town Mashiko (Togei Messe 92–94, 100 (Denkigai), 7, 212 Mashiko), 257 Aoyama, 92 All Nippon Airways, 34, 39 Crafts Gallery (Bijutsukan arcades in hotels, 205 AMDA International Medical Kogeikan), 173 Asakusa, 88–90, 96–97 Information Center, 54 Hakone Art Museum, 268 best bets, 8–10 American Airlines, 34 Hara Museum of busy times, 64–65 American Express Contemporary Art capsule hotels, 97 emergency number, 57 (Hara Bijutsukan), 170 Ebisu, 75–76 traveler’s checks, 17 Japan Ukiyo-e Museum expensive, 79–86 American Pharmacy, 54 (Matsumoto), 206 family-friendly, 75 Ameya Yokocho, 46, 196, Mori Art Museum (Mori Ginza, 71, 79–80, 87 215–216 Bijutsukan), 170–171 Hakone, 270–272 Amida (Kamakura), 247 Museum of Contemporary Hibiya, 79–80 Amusement and theme Art, Tokyo (MOT; Tokyo-to Ikebukuro, 101 parks Gendai Bijutsukan), 171 inexpensive, 95–101 Hanayashiki, 178–179, 188 Narukawa Art Museum Japanese-style, 65–68 LaQua, 179 (Moto-Hakone), 269–270 love hotels, -

Enmusubi Perfect Ticket Model Courses

How to use Enmusubi Perfect Ticket Model Courses Making the most of A complete guide for the areas Enmusubi around Matsue Castle and the City of Matsue Perfect Ticket Use Enmusubi Perfect Ticket Use smart and enjoy Matsue! Sunset at Shinji-ko Lake In the evening in the lake city, the deep red setting sun dyes Shinji-ko Lake with the same color as itself while the sky changes its color from blue to orangey gold. The beauty of such a magical view becomes an unforgettable memory for all who visit the lake. MATSUE Published by: Planning Division, Ichibata Electric Railway Co., Ltd MATSUE In cooperation with: Matsue City Printed by: Watanabe Printing Co., Ltd Tourist Guidebook Photos by: Masanobu Ito Model: JENNIFA 2012.1 Matsue & Izumo free train & bus excursion ticket “Enmusibi Perfect Ticket” User’s Guide - Lake and River City Matsue - the way to enjoy the every corner of Matsue using trains and buses its history and culture Use buses as much as you want for 3 days!! A city that once thrived as a Castle Town and still retains its look in the old days. Ticket with a variety The city that lies amid the calm waterside landscape is dubbed “Lake and River City”. of special deals!! Stroll around in the historic streets and, after a day of walking, Hand this slip to sit by the lake and watch it reflect the color of the setting sun. the attendant on the train to You will surely encounter breathtaking scenery you have never seen before! get Lake Line Free Ticket. -

FESTIVALS Worship, Four Elements of Worship, Worship in the Home, Shrine Worship, Festivals

PLATE 1 (see overleaf). OMIVA JINJA,NARA. Front view of the worshipping hall showing the offering box at the foot of the steps. In the upper foreground is the sacred rope suspended between the entrance pillars. Shinto THE KAMI WAY by DR. SOKYO ONO Professor, Kokugakuin University Lecturer, Association of Shinto Shrines in collaboration with WILLIAM P. WOODARD sketches by SADAO SAKAMOTO Priest, Yasukuni Shrine TUTTLE Publishing Tokyo | Rutland, Vermont | Singapore Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd., with editorial offices at 364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon, VT 05759 USA and 61 Tai Seng Avenue #02-12, Singapore 534167. © 1962 by Charles E. Tuttle Publishing Company, Limited All rights reserved LCC Card No. 61014033 ISBN 978-1-4629-0083-1 First edition, 1962 Printed in Singapore Distributed by: Japan Tuttle Publishing Yaekari Building, 3rd Floor 5-4-12 Osaki, Shinagawa-ku Tokyo 141-0032 Tel: (81)3 5437 0171; Fax: (81)3 5437 0755 Email: [email protected] North America, Latin America & Europe Tuttle Publishing 364 Innovation Drive North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436 USA Tel: 1 (802) 773 8930; Fax: 1 (802) 773 6993 Email:[email protected] www.tuttlepublishing.com Asia Pacific Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd. 61 Tai Seng, Avenue, #02-12 Singapore 534167 Tel: (65) 6280 1330; Fax: (65) 6280 6290 Email: [email protected] www.periplus.com 15 14 13 12 11 10 38 37 36 35 34 TUTTLE PUBLISHING® is a registered trademark of Tuttle Publishing, a division of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. CONTENTS Foreword -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Shiodome, 106–108 Antique Jamboree, 38 Shuzenji, 304 Antique Mall Ginza, 226 surfing online for, 89–90 Antiques and curios, Bathing Ape, 238 A taxes and service charges, 226–227 Accommodations, 81–121. 87 Aoyama, 72 See also Accommodations tips on, 88 accommodations, 110–111 Index Ueno, 116–118 restaurants, 147–153 Akasaka, 96–97, 101–104, very expensive, 90–98 shopping, 237 111–112, 119 Welcome Inn Reservation walking tour, 209–213 Aoyama, 110–111 Center, 88–89 Apple Store, 61 arcades in hotels, 227 Western-style, 86 Aqua City, 228 Asakusa, 108–110, Acupuncture, 181 Aquarium 114–116 Addresses, finding, 68 Sunshine International, Atami, 301–302 Advocates, 265 201 best, 3–4, 81–82 Agave, 261 Tokyo Sea Life Park (Kasai capsule hotels, 115 Airport Limousine Bus Rinkai Suizokuen), 202 with double beds or twin from Haneda Airport, 45 Yokohama Hakkeijima Sea beds, 107 from Narita Airport, 44 Paradise, 287–288 Ebisu, 95–96 Air travel, 42–43 Arcades and shopping malls, eco-friendly, 57 Aka Renga (Red Brick Ware- 227–228 expensive, 98–106 house; Yokohama), 286 Area codes, 306 family-friendly, 96 Akasaka Art galleries, 228–229 Ginza and environs, 83–86, accommodations, 96–97, Artisans of Leisure, 58 90, 98, 106–108 101–104, 111–112, 119 Art museums, 187–192 Hakone, 295–296 nightlife, 252–253, 263– Bridgestone Museum of Hibiya, 98 264 Art (Bridgestone Bijutsu- Ikebukuro, Toyoko Inn Ike- restaurants, 165–169 kan), 187 bukuro Kita-guchi No. 1, Akihabara (Akiba), 70, 225, Crafts -

National Institute of Polar Research 2020-2021

Inter-University Research Institute Corporation Research Organization of Information and Systems 2020-2021 Polar Research Information Observations Support Ellesmere Island Taymyr Peninsula Victoria International Island Collaboration Site Banks Polar Collaborative Island Outreach IBCB (Russia) Research Research International Collaboration Site Spa (Russia) RUSSIA International Collaboration Site Alaska (USA) IARC (USA) CONTENTS Foreword 3 What we do 4 About ROIS 5 National Institute of Polar Research Organization Chart 6 Research Groups 8 Research Projects 13 Center for Antarctic programs 19 Arctic Environment Research Center 20 Arctic Challenge for Sustainability (ArCS II) 21 Collaborative Research 22 Research Support 25 Polar Science Museum, National Institute of Polar Research 32 Graduate Education 34 Organization 35 Institute Data 36 Research Staff 37 Partnership Agreements 40 NIPR in numbers 42 History 43 Photo: Akihiro TACHIMOTO, JARE51 2 FOREWORD The Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition (JARE) activities were first initiated in the middle of the Cold War in 1956. After the Cold War, arctic research of Japan officially started by establishing a station in Svalbard, Norway, in 1991. Founded in 1973, National Institute of Polar Research(NIPR) is an inter-university research institute that conducts comprehensive scientific research and observations in the polar regions. As one of the four institutes constituting the Research Organization of Information and Systems (ROIS), NIPR's continuous contributions benefit research universities -

Gourmet Guide

ACCESS GUIDE H t i o Akasaka t s Mitsuke akasaka Biz Tower u M g Station i u is akasaka S r t SHOPS & DINING j e Sacas i S e M r t t a e T r e u a t n m o S h uc o TBS Akasaka a t c b o Akasaka the Residence ACT Theater h L i i ri o S i r t ne TBS e S e r Broadcasting t MyNavi t Gourmet e Hie Center Blitz Akasaka e t Jinja Hitotsugi Park Akas tation ak Akasaka S a St reet Kokusai Kokusai Chiyoda Line Guide Shin-Akasaka Shin-Akasaka Building West Building East G i n z a Enjoy a wide variety of Hikawa Park Line Japanese flavors Akasaka Kokusai Hikawa akasaka Biz Tower Tameike Shrine Akasaka Sanno SHOPS & DINING Building Station akasaka Biz Tower SHOPS & DINING 【Address】5-3-1 Akasaka, Minato-ku,Tokyo 107-6301 【Access】Tokyo Metro Chiyoda Line Akasaka Station Direct access from exits 1, 3a, and 3b. 【Hours】[Apparel, goods & services] 11:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. [Dining] 11:00 a.m. to 11:30 p.m. Varies by shop/restaurant. Scan here for more information about akasaka Biz Tower SHOPS & DINING! Sushi, one of Japan’s signature dishes, is thinly sliced fish placed on bite-size blocks of rice. The rice is cooked simple, but in a special way so that chefs’ skills become essential. One popular type of sushi is maki-rolled sushi that wraps This One! seafood and other ingredients with rice in nori seaweed. -

The Sacred Art of Metallurgy

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 1991 The as cred art of metallurgy : Heidi Moyer Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Moyer, Heidi, "The as cred art of metallurgy :" (1991). Theses and Dissertations. 5463. https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd/5463 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ,, . ,'' THE SACRED ART OF METALLURGY: THE KANAYAKO TRADITION OF JAPANESE IRON AND FORGE WORKERS by: Heidi ·Moyer A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh ·university in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts . In Social Relations Lehigh University 1991 This thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ma~ters of Arts. !kw1 /] / l'f tj) r I Date Professor in Charge hairman of Department .. 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Prof. Michael Notis for his support and encouragement and m.y committee members, Drs. Barbara Frankel., Nicola Tannenbaum, and Norman Girardot. I would also like to acknowledge the many hours of work ::· contributed by Miss Mia Itasaki and Mrs. Sherilyn Twork. Their assistance with translating the Japanese literature is greatly appreciated. Ill TABLE OF CONTENTS CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL . .. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . • . .. iii TABLE· OF CONTENTS . .. iv LIST OF lLLUSTRATIO NS . • . v ABSTRACT ......................... ! • • • • • • • .• • • • • • • • • • • 1 INTRODUCfION . 2 CHAPTER I. MYTH AND METALLURGY . 4 Methodology and Comparative Theories . 13 a) Technician of the Sacred: Shaman and Smith . -

Kokugakuin Japan Studies

Kokugakuin Japan Studies 2021 | Nº 02 Kokugakuin Japan Studies Volume 2, 2021 Contents 1 Editorial Intent 3 Portrait of the Solitary Empress: Genmei Tennō in Man’yōshū TOSA HIDESATO 37 The Composition of the “Plum-blossom Poems” in Man’yōshū ŌISHI YASUO 57 Japan’s Imperial Household Rites: Meaning, Significance, and Current Situation MOTEGI SADASUMI Editorial Intent Special Number: The Emperor and the Japanese Culture In 2019, the imperial succession rites were conducted and Japan entered a new era referred to as Reiwa 令和, leaving behind the previous Heisei 平成 period. The new emperor formally ascended to the Chrysanthemum throne, and the former one became emperor emeritus. However, when Japan shifted from Shōwa 昭和 to Heisei in 1989, it was because the Shōwa emperor had passed away, not as a result of an abdication as in 2019. For this reason, among others, in 2019 many Japanese seemed to welcome the change of era in a celebratory mood. For example, as the new imperial era “Reiwa” takes its name from ancient poetry, the region in which those poems were read for the first time became a frequent topic in conversations. Also, numerous worshippers paid visit to sanctuaries to receive the seal stamp commemorative of Reiwa’s first year. In other contexts, people often talked about the scarcity of heirs to Japan’s throne, and the possibility of a future empress was extensively debated. Any topic related to “the emperor” received wide media coverage, and interest on the subject increased throughout the country. In that Japanese culture revolves around the emperor’s figure, his presence is an element of the utmost importance in rituals, religion and culture. -

The Incredible Power of Serendipity! Highlights of an Uncommon Life!

The Incredible Power of Serendipity! Highlights Of an Uncommon Life! —A Very Personal Memoir— A VERY PERSONAL MEMOIR Photo by Scott Holland Life isn’t about finding yourself. Life is about creating yourself. —George Bernard Shaw— II A VERY PERSONAL MEMOIR The Incredible Power of Serendipity! Highlights Of an Uncommon Life! —A Very Personal Memoir— Boyé Lafayette De Mente Phoenix Books / Publishers Copyright © 2012 by Boyé Lafayette De Mente All Rights Reserved III A VERY PERSONAL MEMOIR CONTENTS Publisher’s Preface My Jack-Off Uncle Again Introduction Impaled on a Log HIGHLIGHTS OF AN Moving to Redford UNCOMMON LIFE Pell Pirtle’s Hole Cutting Winnie’s Tongue! Sex Education 101 & 102 Doorway Squirrel Shoot! Avoiding Sunday School Killing a Pig The Death of Uncle Bill Shattering an Elbow My First Movie Deer Hunting & The Poisonous Snake Bite Rattlesnakes Going into Business Running Over Winnie Holy Roller Entertainment Moving to Sawmill Shack On the Dole An Untimely Death Struck by Lightning Killing a Chicken Sex Ed 103 Fern & the Hornet Attack Logging with Dad School & Golden Cory Working in a Sawdust Pit My Nose in a Circle Dad’s Copper SS Card Almost Losing Fern The Move to St. Louis Dad Loses a Thumb Clinton-Peabody School Coon Hunting Pearl Harbor 1941 Moving up the Valley & Becoming a Paperboy L’s Arrival My First Boxing Match The Shack that Dad Built Visiting Mother Evans Living on Potatoes Hawking Stolen Goods My Jack-Off Uncle Starting High School Flying off the Truck Working at the Lennox Hanging a Dog Hotel Chopping Down a Tree Discovering an Allergy Hitting Don with an Ax Learning about Life Moving Again My Second Boxing Match The Bologna & Cracker The Arizona Connection Treat The New Mexico Adventure Freezing for Pine Nuts The End of World War II The Chicken Pox Escapade Joining the State Guard Curling Wagon Wheel Hub Sailing on the Mississippi Rings Joining the Navy Losing a Toe Nail Getting to San Diego IV A VERY PERSONAL MEMOIR The Boot Camp Experience Service.