CS 214 040 AUTHOR TITLE Global Perspectives on Teaching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PICTORIAL POSTCARDS of a COLONIAL CITY: the "DREAM- WORK" of JAPANESE IMPERIAL- ISM Won Gi Jung

Won Gi Jung 39 PICTORIAL POSTCARDS OF A COLONIAL CITY: THE "DREAM- WORK" OF JAPANESE IMPERIAL- ISM Won Gi Jung Introduction by Yumi Moon, Associate Professor of His- tory, Stanford University The Japanese empire produced many kinds of visual sources in governing its colonies. Won Gi Jung focuses on postcards of colonial Korea collected in the LUNA Archive of the University of Chicago, analyzing their pictorial narratives and the contexts in which they were made and consumed. Comparing Japan’s case with Western colonialism, Won Gi associates the fourishing postcard industry with the development of modern tourism in the Japanese metropole. He also accentuates Japan’s interest in using foreign tourism to present positive images of its empire to the world. For this reason it was the colonial state of Korea, rather than private studios, that produced the postcards, carefully curating the images of main tourist sites in Keijō (present-day Seoul) and elsewhere. Won Gi also discusses several publications by Western tourists who visited colonial Korea and offers a balanced commen- tary on the colonial state’s “dreamlike” representation of Keijō. Pictorial Postcards 40 Pictorial Postcards of a Colonial City: The "dreamwork" of Japanese Imperialism Won Gi Jung It’s because she found only one or two ‘Korean-made’ products… The [Australian] mistress wanted to purchase Joseon costume for female, but she couldn’t fnd any ready-made clothes. She said, “How come I cannot fnd even one pictorial postcard made by Koreans?”1 Blooming cherry blossom trees adorn the streets of spring- time Keijo.2 A Shinto shrine, dedicated to the Japanese sun-god- dess Amaterasu, stands with dignity at the center of the city.3 Street signs and brochures written in Japanese fll a crowded market- place.4 Tourists saw these landscapes in pictorial postcards sold at train stations, private studios, or near historical sites in colonial Korea. -

Walt Whitman, Where the Future Becomes Present, Edited by David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson

7ALT7HITMAN 7HERETHE&UTURE "ECOMES0RESENT the iowa whitman series Ed Folsom, series editor WALTWHITMAN WHERETHEFUTURE BECOMESPRESENT EDITEDBYDAVIDHAVENBLAKE ANDMICHAELROBERTSON VOJWFSTJUZPGJPXBQSFTTJPXBDJUZ University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 2008 by the University of Iowa Press www.uiowapress.org All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The University of Iowa Press is a member of Green Press Initiative and is committed to preserving natural resources. Printed on acid-free paper issn: 1556–5610 lccn: 2007936977 isbn-13: 978-1-58729–638-3 (cloth) isbn-10: 1-58729–638-1 (cloth) 08 09 10 11 12 c 5 4 3 2 1 Past and present and future are not disjoined but joined. The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is. He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet .... he says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you. He learns the lesson .... he places himself where the future becomes present. walt whitman Preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass { contents } Acknowledgments, ix David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson Introduction: Loos’d of Limits and Imaginary Lines, 1 David Lehman The Visionary Whitman, 8 Wai Chee Dimock Epic and Lyric: The Aegean, the Nile, and Whitman, 17 Meredith L. -

A Propósito De La Filosofía Del Cine Como Educación De Adultos: La Lógica Del Matrimonio Frente Al Absurdo En La Filmografía De Gregory La Cava Hasta 1933

A PROPÓSITO DE LA FILOSOFÍA DEL CINE COMO EDUCACIÓN DE ADULTOS: LA LÓGICA DEL MATRIMONIO FRENTE AL ABSURDO EN LA FILMOGRAFÍA DE GREGORY LA CAVA HASTA 1933 José Alfredo Peris Cancioa Fechas de recepción y aceptación: 2 de junio de 2015, 8 de julio de 2015 Resumen: Desde una concepción de la filosofía del cine como educación de adultos, se puede proponer que la aportación más genuina de la filmografía de La Cava a la expresión de la interrelación entre matrimonio y crisis económica se encuentra en la figura de los antihéroes. Con estos personajes, La Cava plantea tanto la necesidad que experimenta el ser humano de las sociedades industriales de remediar la angustia que le produce su propia debilidad y vulnerabilidad, como la necesidad de entablar relaciones de ayuda. Desde su participación en el cine de animación, así como en sus películas de cine mudo y en sus películas habladas, los protagonistas superan sus propias limitaciones gracias a relaciones de confianza con los demás, de las que el matrimonio igualitario y de mutua ayuda entre el varón y la mujer es el modelo más pleno. Palabras clave: matrimonio, confianza, antihéroes, vulnerabilidad, igualdad y com- plementariedad entre varón y mujer, ayuda, filosofía del cine, educación de adultos. Abstract: From a conception of philosophy of films education of grownups, it can be proposed that the most genuine contribution of the films of La Cava to the expression of the interrelation between marriage and economic crisis is found in the figure of the anti-heroes. With these characters La Cava presents both the need experienced by peo- ple in industrial societies to remedy the distress caused by his own weakness and vulner- a Facultad de Filosofía, Antropología y Trabajo Social, Universidad Católica de Valencia San Vicente Mártir. -

The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018)

The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018) Contents ARTICLES Mother, Monstrous: Motherhood, Grief, and the Supernatural in Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Médée Shauna Louise Caffrey 4 ‘Most foul, strange and unnatural’: Refractions of Modernity in Conor McPherson’s The Weir Matthew Fogarty 17 John Banville’s (Post)modern Reinvention of the Gothic Tale: Boundary, Extimacy, and Disparity in Eclipse (2000) Mehdi Ghassemi 38 The Ballerina Body-Horror: Spectatorship, Female Subjectivity and the Abject in Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977) Charlotte Gough 51 In the Shadow of Cymraeg: Machen’s ‘The White People’ and Welsh Coding in the Use of Esoteric and Gothicised Languages Angela Elise Schoch/Davidson 70 BOOK REVIEWS: LITERARY AND CULTURAL CRITICISM Jessica Gildersleeve, Don’t Look Now Anthony Ballas 95 Plant Horror: Approaches to the Monstrous Vegetal in Fiction and Film, ed. by Dawn Keetley and Angela Tenga Maria Beville 99 Gustavo Subero, Gender and Sexuality in Latin American Horror Cinema: Embodiments of Evil Edmund Cueva 103 Ecogothic in Nineteenth-Century American Literature, ed. by Dawn Keetley and Matthew Wynn Sivils Sarah Cullen 108 Monsters in the Classroom: Essays on Teaching What Scares Us, ed. by Adam Golub and Heather Hayton Laura Davidel 112 Scottish Gothic: An Edinburgh Companion, ed. by Carol Margaret Davison and Monica Germanà James Machin 118 The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018) Catherine Spooner, Post-Millennial Gothic: Comedy, Romance, and the Rise of Happy Gothic Barry Murnane 121 Anna Watz, Angela Carter and Surrealism: ‘A Feminist Libertarian Aesthetic’ John Sears 128 S. T. Joshi, Varieties of the Weird Tale Phil Smith 131 BOOK REVIEWS: FICTION A Suggestion of Ghosts: Supernatural Fiction by Women 1854-1900, ed. -

Japanese Literature Quiz Who Was the First Japanese Novelist to Win the Nobel Prize for Literature?

Japanese Literature Quiz Who was the first Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasunari Kawabata ② Soseki Natsume ③ Ryunosuke Akutagawa ④ Yukio Mishima Who was the first Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasunari Kawabata ② Soseki Natsume ③ Ryunosuke Akutagawa ④ Yukio Mishima Who was the second Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasushi Inoue ② Kobo Abe ③ Junichiro Tanizaki ④ Kenzaburo Oe Who was the second Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasushi Inoue ② Kobo Abe ③ Junichiro Tanizaki ④ Kenzaburo Oe What is the title of Soseki Natsume's novel, "Wagahai wa ( ) de aru [I Am a ___]"? ① Inu [Dog] ② Neko [Cat] ③ Saru [Monkey] ④ Tora [Tiger] What is the title of Soseki Natsume's novel, "Wagahai wa ( ) de aru [I Am a ___]"? ① Inu [Dog] ② Neko [Cat] ③ Saru [Monkey] ④ Tora [Tiger] Which hot spring in Ehime Prefecture is written about in "Botchan," a novel by Soseki Natsume? ① Dogo Onsen ② Kusatsu Onsen ③ Hakone Onsen ④ Arima Onsen Which hot spring in Ehime Prefecture is written about in "Botchan," a novel by Soseki Natsume? ① Dogo Onsen ② Kusatsu Onsen ③ Hakone Onsen ④ Arima Onsen Which newspaper company did Soseki Natsume work and write novels for? ① Mainichi Shimbun ② Yomiuri Shimbun ③ Sankei Shimbun ④ Asahi Shimbun Which newspaper company did Soseki Natsume work and write novels for? ① Mainichi Shimbun ② Yomiuri Shimbun ③ Sankei Shimbun ④ Asahi Shimbun When was Murasaki Shikibu's "Genji Monogatari [The Tale of Genji] " written? ① around 1000 C.E. ② around 1300 C.E. ③ around 1600 C.E. ④ around 1900 C.E. When was Murasaki Shikibu's "Genji Monogatari [The Tale of Genji] " written? ① around 1000 C.E. -

Soseki's Botchan Dango ' Label Tamanoyu Kaminoyu Yojyoyu , The

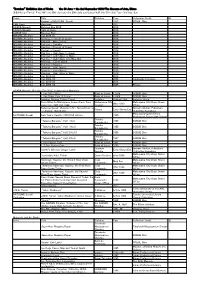

"Botchan" Exhibition List of Works the 30 June - the 2nd September 2018/The Museum of Arts, Ehime ※Exhibition Period First Half: the 30th Jun sat.-the 29th July sun/Latter Half: the 31th July Tue.- 2nd Sep. Sun Artist Title Piblisher Year Collection Credit ※ Portrait of NATSUME Soseki 1912 SOBUE Shin UME Kayo Botchans' 2017 ASADA Masashi Botchan Eye 2018' 2018 ASADA Masashi Cats at Dogo 2018 SOBUE Shin Botchan Bon' 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2018-01 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - White Heron 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Camellia 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi-Neko in Green 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko at Night 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko with Blue Sky 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Turner Island 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Pegasus 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 1 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 2 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko in White 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2013-03 2013 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2002-02 2002 Takahashi Collection MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2014-02 2014 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2006-04 2006 Private ASADA Masashi 'Botchan Eye 2018' Collaboration Materials 1 Yen Bill (2 Bills) Bank of Japan c.1916 SOBUE Shin 1 Yen Silver Coin (3 Coins) Bank of Japan c.1906 SOBUE Shin Iyotetsu Railway Ticket (Copy) Iyotetsu Original:1899 Iyotetsu Group From Mitsu to Matsuyama, Lower Class, Fare Matsuyama City Matsuyama City Dogo Onsen after 1950 3sen 5rin , 28th Oct.,1888 Tourism Office Natsume Soseki, Botchan 's Inn Yamashiroya is Iwanami Shoten, Publishers. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

The Limits of Communication Between Mortals and Immortals in the Homeric Hymns

Body Language: The Limits of Communication between Mortals and Immortals in the Homeric Hymns. Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bridget Susan Buchholz, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Sarah Iles Johnston Fritz Graf Carolina López-Ruiz Copyright by Bridget Susan Buchholz 2009 Abstract This project explores issues of communication as represented in the Homeric Hymns. Drawing on a cognitive model, which provides certain parameters and expectations for the representations of the gods, in particular, for the physical representations their bodies, I examine the anthropomorphic representation of the gods. I show how the narratives of the Homeric Hymns represent communication as based upon false assumptions between the mortals and immortals about the body. I argue that two methods are used to create and maintain the commonality between mortal bodies and immortal bodies; the allocation of skills among many gods and the transference of displays of power to tools used by the gods. However, despite these techniques, the texts represent communication based upon assumptions about the body as unsuccessful. Next, I analyze the instances in which the assumed body of the god is recognized by mortals, within a narrative. This recognition is not based upon physical attributes, but upon the spoken self identification by the god. Finally, I demonstrate how successful communication occurs, within the text, after the god has been recognized. Successful communication is represented as occurring in the presence of ritual references. -

The Making of Modern Japan

The Making of Modern Japan The MAKING of MODERN JAPAN Marius B. Jansen the belknap press of harvard university press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 2000 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Third printing, 2002 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2002 Book design by Marianne Perlak Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jansen, Marius B. The making of modern Japan / Marius B. Jansen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-674-00334-9 (cloth) isbn 0-674-00991-6 (pbk.) 1. Japan—History—Tokugawa period, 1600–1868. 2. Japan—History—Meiji period, 1868– I. Title. ds871.j35 2000 952′.025—dc21 00-041352 CONTENTS Preface xiii Acknowledgments xvii Note on Names and Romanization xviii 1. SEKIGAHARA 1 1. The Sengoku Background 2 2. The New Sengoku Daimyo 8 3. The Unifiers: Oda Nobunaga 11 4. Toyotomi Hideyoshi 17 5. Azuchi-Momoyama Culture 24 6. The Spoils of Sekigahara: Tokugawa Ieyasu 29 2. THE TOKUGAWA STATE 32 1. Taking Control 33 2. Ranking the Daimyo 37 3. The Structure of the Tokugawa Bakufu 43 4. The Domains (han) 49 5. Center and Periphery: Bakufu-Han Relations 54 6. The Tokugawa “State” 60 3. FOREIGN RELATIONS 63 1. The Setting 64 2. Relations with Korea 68 3. The Countries of the West 72 4. To the Seclusion Decrees 75 5. The Dutch at Nagasaki 80 6. Relations with China 85 7. The Question of the “Closed Country” 91 vi Contents 4. STATUS GROUPS 96 1. The Imperial Court 97 2. -

The Post-Postmodern Aesthetics of John Fowles Claiborne Johnson Cordle

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1981 The post-postmodern aesthetics of John Fowles Claiborne Johnson Cordle Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Cordle, Claiborne Johnson, "The post-postmodern aesthetics of John Fowles" (1981). Master's Theses. Paper 444. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POST-POSTMODERN AESTHETICS OF JOHN FOWLES BY CLAIBORNE JOHNSON CORDLE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF ~.ASTER OF ARTS ,'·i IN ENGLISH MAY 1981 LTBRARY UNIVERSITY OF RICHMONl:» VIRGINIA 23173 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . p . 1 CHAPTER 1 MODERNISM RECONSIDERED . p • 6 CHAPTER 2 THE BREAKDOWN OF OBJECTIVITY . p • 52 CHAPTER 3 APOLLO AND DIONYSUS. p • 94 CHAPTER 4 SYNTHESIS . p . 102 CHAPTER 5 POST-POSTMODERN HUMANISM . p . 139 ENDNOTES • . p. 151 BIBLIOGRAPHY . • p. 162 INTRODUCTION To consider the relationship between post modernism and John Fowles is a task unfortunately complicated by an inadequately defined central term. Charles Russell states that ... postmodernism is not tied solely to a single artist or movement, but de fines a broad cultural phenomenon evi dent in the visual arts, literature; music and dance of Europe and the United States, as well as in their philosophy, criticism, linguistics, communications theory, anthropology, and the social sciences--these all generally under thp particular influence of structuralism. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ............................................................................................................................... -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51.