Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference Guide for the History of English

Reference Guide for the History of English Raymond Hickey English Linguistics Institute for Anglophone Studies University of Duisburg and Essen January 2012 Some tips when using the Reference Guide: 1) To go to a certain section of the guide, press Ctrl-F and enter the name of the section. Alternatively, you can search for an author or the title of a book. 2) Remember that, for reasons of size, the reference guide only includes books. However, there are some subjects for which whole books are not readily available but only articles. In this case, you can come to me for a consultation or of course, you can search yourself. If you are looking for articles on a subject then one way to find some would be to look at a standard book on the (larger) subject area and then consult the bibliography at the back of the book., To find specific contents in a book use the table of contents and also the index at the back which always offers more detailed information. If you are looking for chapters on a subject then an edited volume is the most likely place to find what you need. This is particularly true for the history of English. 3) When you are starting a topic in linguistics the best thing to do is to consult a general introduction (usually obvious from the title) or a collection of essays on the subject, often called a ‘handbook’. There you will find articles on the subareas of the topic in question, e.g. a handbook on varieties of English will contain articles on individual varieties, a handbook on language acquisition will contain information on various aspects of this topic. -

Leeds Working Papers in Linguistics and Phonetics

LWPLP Leeds Working Papers in Linguistics and Phonetics The University of Leeds Volume 18, 2013 Leeds Working Papers in Linguistics and Phonetics Volume 18, 2013 Editors: David Wright, Marilena Di Bari, Christopher Norton, Ashraf Abdullah and Ruba Khamam Contents Christopher Norton and David Wright ii–iii Editorial preface Alaric Hall 1–33 Jón the Fleming: Low German in Thirteenth-Century Norway and Fourteenth-Century Iceland Barry Heselwood and Janet C. E. Watson 34–53 The Arabic definite article does not assimilate Sandra Nickel 54–84 Spreading which word? Philological, theological and socio-political con- siderations behind the nineteenth-century Bible translation into Yorùbá Mary Alice Sanigar 85–114 Selling an Education. Universities as commercial entities: a corpus-based study of university websites as self-promotion Abdurraouf Shitaw 115–132 Gestural phasing of tongue-back and tongue-tip articulations in Tripoli- tanian Libyan Arabic Marilena Di Bari 133–137 An interview with Marina Manfredi on the use of systemic functional linguistics, and other ways of teaching translation studies Ran Xu 138–141 An interview with Dr. Franz Pöchhacker on interpreting research and training Norton and Wright LWPLP, 18, 2013 Editorial Preface Chris Nortona and David Wrightb aThe University of Leeds, UK; [email protected] bThe University of Leeds, UK; [email protected] Leeds Working Papers in Linguistics and Phonetics (LWPLP) is a peer- reviewed journal which publishes reports on research in linguistics, lan- guage studies, phonetics, and translation studies by staff and students at the University of Leeds. First published in 1983, the journal was revived in 1998 by Paul Foulkes (now at the University of York) and Diane Nelson. -

Publications in Pers Format

1 Curriculum Vitae Robert P. Stockwell Professor Emeritus, Department of Linguistics, UCLA Address: (Home) 4000 Hayvenhurst Ave, Encino, CA 91436 (Office) Department of Linguistics, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095 Phone: (Home) (818) 783-1719 (Office) (310) 925-8675 E-Mail: [email protected] Born June 12, 1925, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Education: BA. (English and Greek) 1946, University of Virginia MA. (English) 1949, University of Virginia Ph.D. (English Philology) 1952, University of Virginia Experience: 1952-56 School of Languages, Foreign Service Institute, Department of State (in charge of Spanish and Portuguese language instruction; co-authored the FSI Spanish text which was the main instructional tool at FSI for the next 20 years and became the principal model for the MLA Modern Spanish and the ALM series of language texts from Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 1956-66 Professor of English, UCLA (Assistant Professor 1956, Associate Professor 1958, Full Professor 1962). Responsible for graduate and undergraduate courses in history and structure of English language. 1966-1994: Professor of Linguistics, UCLA. Responsible for graduate and undergraduate courses in historical linguistics, history of English, syntactic theory, historical theory. 1994--: Professor Emeritus, Recalled to Active Service 1994-1999, Department of Linguistics, UCLA 1963-66 Chair, Interdepartmental Program in Linguistics, UCLA 1966-73 Founding Chair, Department of Linguistics, UCLA 1980-84 Chair, Department of Linguistics, UCLA Visiting professorships (summers): 1955, 1956 -

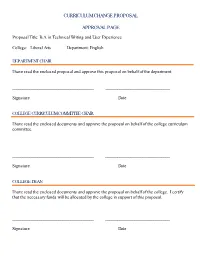

Curriculum Change Proposal Approval Page

CURRICULUM CHANGE PROPOSAL APPROVAL PAGE Proposal Title: B.A. in Technical Writing and User Experience College: Liberal Arts Department: English DEPARTMENT CHAIR I have read the enclosed proposal and approve this proposal on behalf of the department. _______________________________________ _______________________________ Signature Date COLLEGE CURRICULUM COMMITTEE CHAIR I have read the enclosed documents and approve the proposal on behalf of the college curriculum committee. _______________________________________ _______________________________ Signature Date COLLEGE DEAN I have read the enclosed documents and approve the proposal on behalf of the college. I certify that the necessary funds will be allocated by the college in support of this proposal. _______________________________________ _______________________________ Signature Date To: From: Lucia Dura, PhD, Assistant Professor and Program Director of Rhetoric and Writing Studies Re: Proposal for BA Degree in Technical Writing and User Experience September 17, 2018 The Rhetoric and Writing Studies program has been thriving at UTEP with its current offerings: ● PhD in Rhetoric and Composition ● MA in Rhetoric and Writing Studies ● Graduate Certificate in Technical and Professional Writing ● Minor in Rhetoric and Writing Studies ● First Year Composition Program The attached proposal for a BA degree in Technical Writing and User Experience (TWUX) is a natural plan that enables us to “round out” our offerings by expanding the current minor (with the addition of only 4 new courses in the major) and by creating a bridge to the MA program. The BA in TWUX aims to anticipate and respond to the demographic, technological, and socio- economic changes facing the students of our region who are positioned to make both a local and a global impact in a variety of industries. -

Leeds Studies in English

Leeds Studies in English New Series XLII 2011 Edited by Alaric Hall Editorial assistants Helen Price and Victoria Cooper Leeds Studies in English <www.leeds.ac.uk/lse> School of English University of Leeds 2011 Reviews Dinah Hazell, Poverty in Late Middle English Literature: The ‘Meene’ and the ‘Riche’. Dublin Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature, 2. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2009. 234 pp. ISBN 978-1-84682-1155-4. £50.00. Dinah Hazell’s book provides a wide-ranging survey of representations of poverty in late fourteenth-century literature. It is structured by four topics or categories: ‘Aristocratic’, ‘Urban’, ‘Rural’, and ‘Apostolic’ poverty. Each section provides the reader with a brief ‘socioeconomic overview’ and a selection of descriptions of the place of poverty in a variety of texts. The breadth of texts discussed is unusual and interesting, and includes work on diverse genres. The section on ‘Aristocratic’ Poverty includes discussions of five Middle English ro- mances: Ywain and Gawain; Sir Amadace; Sir Cleges; Sir Launfal; and Sir Orfeo. The chapter on ‘Urban’ poverty contains some brief discussion of Havelok; ‘London Lickpenny’; Hoccleve’s Regiment of Princes; Chaucer’s Prioress’s Tale; and The Simonie. The section on ‘Rural’ poverty is dedicated to more substantial discussions of Chaucer (again), in the form of the Clerk’s and Nun’s Priest’s Tales, and of the various Shepherds’ Plays in the York, Chester, Coventry and Towneley cycles (with a natural emphasis on the Towneley Prima and Secunda Pastorum). The chapter on ‘Apostolic’ poverty is largely focused on anticlerical and antifraternal themes, such as those in Gower’s Vox Clamantis, The Land of Cockaygne, and Pierce the Ploughman’s Crede. -

The Visual Craft of Old English Verse: Mise-En-Page in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts

The visual craft of Old English verse: mise-en-page in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts Rachel Ann Burns UCL PhD in English Language and Literature 1 I, Rachel Ann Burns confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Rachel Ann Burns 2 Table of Contents Abstract 8 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 12 List of images and figures 13 List of tables 17 CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 18 Organisation of the page 26 Traditional approaches to Old English verse mise-en-page 31 Questions and hypotheses 42 Literature review and critical approaches 43 Terminology and methodologies 61 Full chapter plan 68 CHAPTER TWO: Demarcation of the metrical period in the Latin verse texts of Anglo-Saxon England 74 Latin verse on the page: classical and late antiquity 80 Latin verse in early Anglo-Saxon England: identifying sample sets 89 New approach 92 Identifying a sample set 95 Basic results from the sample set 96 Manuscript origins and lineation 109 Order and lineation: acrostic verse 110 3 Order and lineation: computistical verse and calendars 115 Conclusions from the sample set 118 Divergence from Old English 119 Learning Latin in Anglo-Saxon England: the ‘shape’ of verse 124 Contrasting ‘shapes’: Latin and Old English composition 128 Hybrid layouts, and the failure of lineated Old English verse 137 Correspondences with Latin rhythmic verse 145 Conclusions 150 CHAPTER THREE: Inter-word Spacing in Beowulf and the neurophysiology of scribal engagement with Old English verse 151 Thesis and hypothesis 152 Introduction of word-spacing in the Latin West 156 Previous scholarship on the significance of inter-word spacing 161 Robert D. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA John Wyclif's Christology

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA John Wyclif’s Christology in Light of De Incarnatione Verbi, Chapter 7 A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Center for Medieval and Byzantine Studies, School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Luke Nathan DeWeese Washington, D.C. 2020 John Wyclif’s Christology in Light of De Incarnatione Verbi, Chapter 7 Luke Nathan DeWeese, Ph.D. Director: Timothy B. Noone, Ph.D. This dissertation begins the work of a full critical edition and translation of Wyclif’s treatise, De incarnatione Verbi (DIV). Chapters 1–4 include full codicological surveys of all eight surviving manuscripts that contain the text; justify the proposed stemma codicum in light of surviving textual variants; argue that the version contained in manuscript M is a reportatio; and explain the need for a new edition to replace Edward Harris’s edition of 1886. Chapters 5–8 contain critical editions and translations of the prologue and seventh chapter of both the reportatio and final version of the treatise. Chapter 9 discusses the treatise’s authenticity, title, genre, and date. Chapter 10 begins the themes-based portion of this dissertation. It contains the most comprehensive account of Wyclif’s Christology yet to appear in print, and advances the state of the question through translations of much hitherto unstudied material. Chapter 11 is a commentary on the material contained in chapters 7 and 8. Chapter 12 considers Wyclif’s use of his sources. Chapter 13 concludes with the intention of giving the reader a sense of a coherent whole. -

Oath-Taking and Oath-Breaking in Medieval Lceland and Anglo-Saxon England

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2014 Bound by Words: Oath-taking and Oath-breaking in Medieval lceland and Anglo-Saxon England Gregory L. Laing Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Laing, Gregory L., "Bound by Words: Oath-taking and Oath-breaking in Medieval lceland and Anglo-Saxon England" (2014). Dissertations. 382. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/382 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOUND BY WORDS: THE MOTIF OF OATH-TAKING AND OATH-BREAKING IN MEDIEVAL ICELAND AND ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND by Gregory L. Laing A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy English Western Michigan University December 2014 Doctoral Committee: Jana K. Schulman, Ph.D., Chair Eve Salisbury, Ph.D. Larry Hunt, Ph.D. Paul E. Szarmach, Ph.D. BOUND BY WORDS: THE MOTIF OF OATH-TAKING AND OATH-BREAKING IN MEDIEVAL ICELAND AND ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND Gregory L. Laing, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2014 The legal and literary texts of early medieval England and Iceland share a common emphasis on truth and demonstrate its importance through the sheer volume of textual references. -

Publications in Pers Format

E-Mail: [email protected] Born June 12, 1925, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Education: BA. (English and Greek) 1946, University of Virginia MA. (English) 1949, University of Virginia Ph.D. (English Philology) 1952, University of Virginia Experience: 1952-56 School of Languages, Foreign Service Institute, Department of State (in charge of Spanish and Portuguese language instruction; co-authored the FSI Spanish text which was the main instructional tool at FSI for the next 20 years and became the principal model for the MLA Modern Spanish and the ALM series of language texts from Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 1956-66 Professor of English, UCLA (Assistant Professor 1956, Associate Professor 1958, Full Professor 1962). Responsible for graduate and undergraduate courses in history and structure of English language. 1966-1994: Professor of Linguistics, UCLA. Responsible for graduate and undergraduate courses in historical linguistics, history of English, syntactic theory, historical theory. 1994--: Professor Emeritus, Recalled to Active Service 1994-1999, Department of Linguistics, UCLA 1963-66 Chair, Interdepartmental Program in Linguistics, UCLA 1966-73 Founding Chair, Department of Linguistics, UCLA 1980-84 Chair, Department of Linguistics, UCLA Visiting professorships (summers): 1955, 1956 Georgetown University; 1960 University of the Philippines; 1961 University of Texas; 1965 University of Michigan; 1979 University of Salzburg. Associate Director, Linguistic Institute at University of Salzburg 1979 Director, Linguistic Institute at UCLA 1983 Honors -

Old English Newsletter

OLD ENGLISH NEWSLETTER Published for !e Old English Division of the Modern Language Association of America by !e Medieval Institute, Western Michigan University and its Richard Rawlinson Center for Anglo-Saxon Studies Editor: R.M. Liuzza Associate Editors: Daniel Donoghue !omas Hall VOLUME NUMBER FALL ISSN - O!" E#$!%&' N()&!(**(+ Volume "# Number $ Fall %&&' Editor Publisher R. M. Liuzza Paul E. Szarmach Department of English Medieval Institute The University of Tennessee Western Michigan University "&$ McClung Tower $#&" W. Michigan Ave. Knoxville, TN "(##)-&*"& Kalamazoo, MI *#&&+-'*"% Associate Editors Year’s Work in Old English Studies OEN Bibliography Daniel Donoghue Thomas Hall Department of English Department of English (M/C $)%) Harvard University University of Illinois at Chicago Barker Center / $% Quincy St. )&$ S. Morgan Street Cambridge MA &%$"+ Chicago, IL )&)&(-($%& Assistant to the Editor: Tara Lynn Assistant to the Publisher: David Clark Subscriptions: The rate for institutions is ,%& -. per volume, current and past volumes, except for volumes $ and %, which are sold as one. The rate for individuals is ,$' -. per volume, but in order to reduce administrative costs the editors ask individuals to pay for two volumes (currently "+ & "#) at one time at the discounted rate of ,%'. Correspondence: General correspondence regarding OEN should be addressed to the Editor; correspondence regard- ing the Year’s Work and the annual Bibliography should be sent to the respective Associate Editors. Correspondence regarding business matters and subscriptions should be sent to the Publisher. Submissions: The Old English Newsletter is a referreed periodical. Solicited and unsolicited manuscripts (except for independent reports and news items) are reviewed by specialists in anonymous reports. Scholars can assist the work of OEN by sending offprints of articles, and notices of books or monographs, to the Edi- tor. -

Edmund Spenser, Lucretian Neoplatonist: Cosmology in the Fowre Hymnes

AYESHA RAMACHANDRAN Edmund Spenser, Lucretian Neoplatonist: Cosmology in the Fowre Hymnes This essay reconsiders the relationship between Spenser’s earthly and divine hymns in terms of the dialogic possibilities of the palinode, suggesting that the apparent ‘‘recantation’’ of the first two hymns is a poetic device used for philosophic effect. I argue that Spenser uses the poetic movement of action and retraction, turn and counterturn, to embody a philosophical oscillation and synthesis between a newly rediscovered Lucretian materialism and the Christian Neoplatonism, traditionally ascribed to the sequence. The stimulus for this seemingly unusual juxtaposition of two fundamentally different philosophies is the subject of the Fowre Hymnes: the poems are not only an expression of personal emotion and faith, but seek to make a significant intervention in the late sixteenth-century revival of cosmology and natural philosophy. Therefore, the essay takes seriously the hymns’ ge- neric claim towards the grand style of philosophic abstraction, showing how Spenser explores the dialectic between matter and form, chaos and creation, mutability and eternity, through his repeated emphasis on the creation. Each hymn contains a dis- tinct creation account; together they contrast a vision of a dy- namic, de-centered, material cosmos (identified textually with the cosmos of Lucretius’s De rerum natura) with the formal sym- metry and stable order of the Christian-Platonic universe. In this syncretic relationship between Lucretius and Plato, Spenser may have seen a powerful model for harmonizing the tradition- ally opposed motivations of poetry and philosophy, and for reconciling, albeit very uneasily, a concern with the flux of worldly experience and a desire to comprehend cosmic stability and formal order. -

British Academy New Fellows 2015 Fellows Professor Janette Atkinson

British Academy New Fellows 2015 Fellows Professor Janette Atkinson FMedSci Emeritus Professor, University College London; Visiting Professor, University of Oxford Professor Oriana Bandiera Professor of Economics, Director of STICERD, London School of Economics Professor Melanie Bartley Emeritus Professor of Medical Sociology, University College London Professor Christine Bell Professor of Constitutional Law, Assistant Principal and Executive Director, Global Justice Academy, University of Edinburgh Professor Julia Black Professor of Law and Pro Director for Research, London School of Economics and Political Science Professor Cyprian Broodbank John Disney Professor of Archaeology and Director, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge Professor David Buckingham Emeritus Professor of Media and Communications, Loughborough University; Visiting Professor, Sussex University; Visiting Professor, Norwegian Centre for Child Research Professor Craig Calhoun Director and School Professor, London School of Economics Professor Michael Carrithers Professor of Anthropology, Durham University Professor Dawn Chatty Professor of Anthropology and Forced Migration, University of Oxford Professor Andy Clark FRSE Professor of Logic and Metaphysics, University of Edinburgh Professor Thomas Corns Emeritus Professor of English Literature, Bangor University Professor Elizabeth Edwards Professor of Photographic History, Director of Photographic History Research Centre, De Montfort University Professor Briony Fer Professor of Art History,