Download Original Attachment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Ta-Nehisi Coates's Between the World and Me

“OVERPOLICED AND UNDERPROTECTED”:1 RACIALIZED GENDERED VIOLENCE(S) IN TA-NEHISI COATES’S BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME “SOBREVIGILADAS Y DESPROTEGIDAS”: VIOLENCIA(S) DE GÉNERO RACIALIZADA(S) EN BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME, DE TA-NEHISI COATES EVA PUYUELO UREÑA Universidad de Barcelona [email protected] 13 Abstract Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me (2015) evidences the lack of visibility of black women in discourses on racial profiling. Far from tracing a complete representation of the dimensions of racism, Coates presents a masculinized portrayal of its victims, relegating black women to liminal positions even though they are one of the most overpoliced groups in US society, and disregarding the fact that they are also subject to other forms of harassment, such as sexual fondling and other forms of abusive frisking. In the face of this situation, many women have struggled, both from an academic and a political-activist angle, to raise the visibility of the role of black women in contemporary discourses on racism. Keywords: police brutality, racism, gender, silencing, black women. Resumen Con la publicación de la obra de Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me (2015) se puso de manifiesto un problema que hacía tiempo acechaba a los discursos sobre racismo institucional: ¿dónde estaban las mujeres de color? Lejos de trazar un esbozo fiel de las dimensiones de la discriminación racial, la obra de Coates aboga por una representación masculinizada de las víctimas, relegando a las miscelánea: a journal of english and american studies 62 (2020): pp. 13-28 ISSN: 1137-6368 Eva Puyuelo Ureña mujeres a posiciones marginales y obviando formas de acoso que ellas, a diferencia de los hombres, son más propensas a experimentar. -

Resources on Race, Racism, and How to Be an Anti-Racist Articles, Books, Podcasts, Movie Recommendations, and More

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” – JAMES BALDWIN DIVERSITY & INCLUSION ————— Resources on Race, Racism, and How to be an Anti-Racist Articles, Books, Podcasts, Movie Recommendations, and More Below is a non-exhaustive list of resources on race, anti-racism, and allyship. It includes resources for those who are negatively impacted by racism, as well as resources for those who want to practice anti-racism and support diverse individuals and communities. We acknowledge that there are many resources listed below, and many not captured here. If after reviewing these resources you notice gaps, please email [email protected] with your suggestions. We will continue to update these resources in the coming weeks and months. EXPLORE Anguish and Action by Barack Obama The National Museum of African American History and Culture’s web portal, Talking About Race, Becoming a Parent in the Age of Black Lives which is designed to help individuals, families, and Matter. Writing for The Atlantic, Clint Smith communities talk about racism, racial identity and examines how having children has pushed him the way these forces shape society to re-evaluate his place in the Black Lives Matter movement: “Our children have raised the stakes of Antiracism Project ― The Project offers participants this fight, while also shifting the calculus of how we ways to examine the crucial and persistent issue move within it” of racism Check in on Your Black Employees, Now by Tonya Russell ARTICLES 75 Things White People Can Do For Racial Justice First, Listen. -

The Black Male Experience in Ta-Nehisi Coates's Between The

YESMINA KHEDHIR The Black Male Experience in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me and The Beautiful Struggle Pro&Contra 2 No. 2 (2018) 49–65. DOI: 10.33033/pc.2018.2.49 THE BLACK MALE EXPERIENCE... 51 Abstract Since the publication of his autobiographical essay Between the World and Me, the African American writer and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates has garnered a wide readership as well as considerable recognition. Both in Between the World and Me (2015) and in his earlier memoir The Beautiful Struggle (2008), Coates traces his own experience as a black male growing up in a poor black neighborhood in West Baltimore. In his work, Coates tackles the major problems faced by black men in today’s America, especially poverty, mass incarceration, drug addiction and dealing, urban violence and police brutality. He contends that the present predicament of black people, and black men in particular, can only be understood in light of the continuous dehumanization, marginalization, and destruction of black bodies. The paper aims to examine Coates’ experience as a black male and to argue that despite his overt pessimism, Coates challenges hegemonic notions of black masculinity and subverts stereotypes about African American men by becoming a caring father and a conscious intellectual. Keywords: Ta-Nehisi Coates, autobiography, black masculinity, black body, manhood Since the publication of his autobiographical essay Between the World and Me (2015) written as a letter to his fifteen-year-old son, the African American writer and journalist Ta-Ne- hisi Coates has garnered a wide readership as well as considerable recognition. -

Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences

Shrews, Moneylenders, Soldiers, and Moors: Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Harelik, M.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Professor Lesley Ferris, Adviser Professor Jennifer Schlueter Professor Shilarna Stokes Professor Robin Post Copyright by Elizabeth Harelik 2016 Abstract Shakespeare’s plays are often a staple of the secondary school curriculum, and, more and more, theatre artists and educators are introducing young people to his works through performance. While these performances offer an engaging way for students to access these complex texts, they also often bring up topics and themes that might be challenging to discuss with young people. To give just a few examples, The Taming of the Shrew contains blatant sexism and gender violence; The Merchant of Venice features a multitude of anti-Semitic slurs; Othello shows characters displaying overtly racist attitudes towards its title character; and Henry V has several scenes of wartime violence. These themes are important, timely, and crucial to discuss with young people, but how can directors, actors, and teachers use Shakespeare’s work as a springboard to begin these conversations? In this research project, I explore twenty-first century productions of the four plays mentioned above. All of the productions studied were done in the United States by professional or university companies, either for young audiences or with young people as performers. I look at the various ways that practitioners have adapted these plays, from abridgments that retain basic plot points but reduce running time, to versions incorporating significant audience participation, to reimaginings created by or with student performers. -

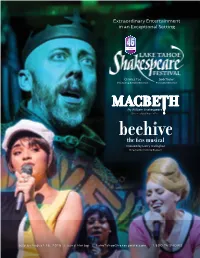

Extraordinary Entertainment in an Exceptional Setting

Extraordinary Entertainment in an Exceptional Setting Charles Fee Bob Taylor Producing Artistic Director Executive Director By William Shakespeare Directed by Charles Fee Created by Larry Gallagher Directed by Victoria Bussert July 6–August 26, 2018 | Sand Harbor | L akeTahoeShakespeare.com | 1.800.74.SHOWS Enriching lives, inspiring new possibilities. At U.S. Bank, we believe art enriches and inspires our community. That’s why we support the visual and performing arts organizations that push our creativity and passion to new levels. When we test the limits of possible, we fi nd more ways to shine. usbank.com/communitypossible U.S. Bank is proud to support the Lake Tahoe Shakespeare Festival. Incline Village Branch 923 Tahoe Blvd. Incline Village, NV 775.831.4780 ©2017 U.S. Bank. Member FDIC. 171120c 8.17 “World’s Most Ethical Companies” and “Ethisphere” names and marks are registered trademarks of Ethisphere LLC. 2018 Board of Directors Patricia Engels, Chair Michael Chamberlain, Vice Chair Atam Lalchandani, Treasurer Mary Ann Peoples, Secretary Wayne Cameron Scott Crawford Katharine Elek Amanda Flangas John Iannucci Vicki Kahn Charles Fee Bob Taylor Nancy Kennedy Producing Artistic Director Executive Director Roberta Klein David Loury Vicki McGowen Dear Friends, Judy Prutzman Welcome to the 46th season of Lake Tahoe Shakespeare Festival, Nevada’s largest professional, non-profit Julie Rauchle theater and provider of educational outreach programming! Forty-six years of Shakespeare at Lake Tahoe D.G. Menchetti, Director Emeritus is a remarkable achievement made possible by the visionary founders and leaders of this company, upon whose shoulders we all stand, and supported by the extraordinary generosity of this community, our board Allen Misher, Director Emeritus of directors, staff, volunteers, and the many artists who have created hundreds of evenings of astonishing Warren Trepp, Honorary Founder entertainment under the stars. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

SUPPORT FOR THE 2021 SEASON OF THE TOM PATTERSON THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY THE HARKINS & MANNING FAMILIES IN MEMORY OF SUSAN & JIM HARKINS LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

Ta-Nehisi Coates' Critique of American Culture And

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Critique of American Culture and Walter J. Ong’s Thought Thomas J. Farrell Professor Emeritus in Writing Studies University of Minnesota Duluth [email protected] Recently I have been re-reading and writing about the American Jesuit cultural historian and theorist Walter J. Ong’s book about the Victorian Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844- 1889), Hopkins, the Self, and God (1986), the expanded published version of Ong’s 1981 Alexander Lectures at the University of Toronto. Hopkins’ poetry was published posthumously in 1918. As the title of Ong’s book indicates, his study of Hopkins centers on Hopkins’ writings about the self, including his poetry but not just on his poetry. Now, in the title of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ short book Between the World and Me (2015), the author announces that he is writing about his sense of his self. Coates writes his autobiographical book as a letter to his 15-year old son, whose first name honors Samori Toure (page 68). So Coates is telling his son the story of his (the son’s) father’s upbringing and how his father met his mother and more. As other reviewers have noted, James Baldwin’s book The Fire Next Time (1963) begins as a letter to Baldwin’s 15-year-old nephew. So perhaps Coates’ new book addressed to his 15-year- old son represents Coates’ bid to become the new Baldwin for the 21st century. Your guess is as good as mine as to whether the book-reading American public today will see Coates as the new Baldwin for the 21st century. -

The Visual Craft of Old English Verse: Mise-En-Page in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts

The visual craft of Old English verse: mise-en-page in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts Rachel Ann Burns UCL PhD in English Language and Literature 1 I, Rachel Ann Burns confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Rachel Ann Burns 2 Table of Contents Abstract 8 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 12 List of images and figures 13 List of tables 17 CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 18 Organisation of the page 26 Traditional approaches to Old English verse mise-en-page 31 Questions and hypotheses 42 Literature review and critical approaches 43 Terminology and methodologies 61 Full chapter plan 68 CHAPTER TWO: Demarcation of the metrical period in the Latin verse texts of Anglo-Saxon England 74 Latin verse on the page: classical and late antiquity 80 Latin verse in early Anglo-Saxon England: identifying sample sets 89 New approach 92 Identifying a sample set 95 Basic results from the sample set 96 Manuscript origins and lineation 109 Order and lineation: acrostic verse 110 3 Order and lineation: computistical verse and calendars 115 Conclusions from the sample set 118 Divergence from Old English 119 Learning Latin in Anglo-Saxon England: the ‘shape’ of verse 124 Contrasting ‘shapes’: Latin and Old English composition 128 Hybrid layouts, and the failure of lineated Old English verse 137 Correspondences with Latin rhythmic verse 145 Conclusions 150 CHAPTER THREE: Inter-word Spacing in Beowulf and the neurophysiology of scribal engagement with Old English verse 151 Thesis and hypothesis 152 Introduction of word-spacing in the Latin West 156 Previous scholarship on the significance of inter-word spacing 161 Robert D. -

Postmaster and the Merton Record 2019

Postmaster & The Merton Record 2019 Merton College Oxford OX1 4JD Telephone +44 (0)1865 276310 www.merton.ox.ac.uk Contents College News Edited by Timothy Foot (2011), Claire Spence-Parsons, Dr Duncan From the Acting Warden......................................................................4 Barker and Philippa Logan. JCR News .................................................................................................6 Front cover image MCR News ...............................................................................................8 St Alban’s Quad from the JCR, during the Merton Merton Sport ........................................................................................10 Society Garden Party 2019. Photograph by John Cairns. Hockey, Rugby, Tennis, Men’s Rowing, Women’s Rowing, Athletics, Cricket, Sports Overview, Blues & Haigh Awards Additional images (unless credited) 4: Ian Wallman Clubs & Societies ................................................................................22 8, 33: Valerian Chen (2016) Halsbury Society, History Society, Roger Bacon Society, 10, 13, 36, 37, 40, 86, 95, 116: John Cairns (www. Neave Society, Christian Union, Bodley Club, Mathematics Society, johncairns.co.uk) Tinbergen Society 12: Callum Schafer (Mansfield, 2017) 14, 15: Maria Salaru (St Antony’s, 2011) Interdisciplinary Groups ....................................................................32 16, 22, 23, 24, 80: Joseph Rhee (2018) Ockham Lectures, History of the Book Group 28, 32, 99, 103, 104, 108, 109: Timothy Foot -

Article from Socially Distant to Socially Engaged: Exploring the Soundscape and Material Environment of Guillaume De Machaut’S Remede De Fortune

Article From Socially Distant to Socially Engaged: Exploring the Soundscape and Material Environment of Guillaume de Machaut’s Remede de Fortune Mahoney-Steel, Tamsyn Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/37960/ Mahoney-Steel, Tamsyn ORCID: 0000-0003-0037-7281 (2021) From Socially Distant to Socially Engaged: Exploring the Soundscape and Material Environment of Guillaume de Machaut’s Remede de Fortune. Digital Philology: A Journal of Medieval Cultures, 10 (1). pp. 64-94. ISSN 2162-9544 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/dph.2021.0003 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk Tamsyn Mahoney-Steel University of Central Lancashire From Socially Distant to Socially Engaged: Exploring the Soundscape and Material Environment of Guillaume de Machaut’s Remede de Fortune Ostensibly a story about gaining confidence in love, Guillaume de 4Machaut’s Remede de Fortune has been explored as a summa of contemporary musical styles and a treatise on the memorial arts.1 It has also been examined as an important example of the use of citation and allusion in the fourteenth century because it incorporates references to Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy and Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun’s Le roman de la Rose. -

St Andrews Institute of Legal and Constitutional Research

St Andrews Institute of Legal and Constitutional Research 2016-17 Report Now in its second year, the St Andrews Institute of Legal and Constitutional Research (ILCR) has built upon its successes in the 2015 - 2016 academic year and experienced another busy, enjoyable, and intellectually stimulat- ing period of activity. Over the past year, the ILCR has enjoyed success in a number of areas: internationally recognised academic pub- lications; innovative public engagement activities; unique research projects; world-leading workshops; and the award of major research grants. At the beginning of the 2016 Martinmas term the ILCR also welcomed the first students on the Institute’s new Legal and Constitutional Research M.Litt, studying a range of topics including international law, political history and medieval and early-modern law. The 2017 - 2018 academic year promises to be equally stimulating. It will witness the first full year of activity on a major ERC Advanced Grant funded project on medieval legal history undertaken within the ILCR, the arrival of the second cohort of students taking the Legal and Constitutional Research M.Litt degree, and the development of further innovative research projects. This report contains information about the activities of the Institute and its members over the course of the 2016 - 2017 academic year. Contents Events and research activities: 2 Conferences and colloquiums: 3 Visiting scholars: 4 Awards and other news: 5 Publications and research: 6 - 7 The Legal and Constitutional Studies M.Litt 2016 - 2017 cohort with Professor Caroline Humfress: Photo - Friederike Ritzmann School of History, University of St Andrews, 71 South Street, St Andrews, Fife, KY16 9QW [email protected] 2016-2017 Events and Research Activities Lectures Annual Lecture (April 2017): The ILCR’s Annual Lecture was given by Professor William Ian Miller (Thomas G. -

Doctors, Dandies and New Men: Ella Hepworth Dixon and Late-Century Masculinities

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Doctors, Dandies and New Men: Ella Hepworth Dixon and Late-Century Masculinities MacDonald, T. DOI 10.1080/09699082.2012.622980 Publication date 2012 Document Version Final published version Published in Women's Writing Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): MacDonald, T. (2012). Doctors, Dandies and New Men: Ella Hepworth Dixon and Late- Century Masculinities. Women's Writing, 19(1), 41-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/09699082.2012.622980 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:24 Sep 2021 This article was downloaded by: [UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek SZ], [Tara MacDonald] On: 09 February 2012, At: 03:30 Publisher: