Spectacles of Suffering: Self-Harm in New Woman Writing 1880-1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Levinas and the New Woman Writers: Narrating the Ethics of Alterity

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 12-10-2018 Levinas and the New Woman Writers: Narrating the Ethics of Alterity Anita Turlington Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Turlington, Anita, "Levinas and the New Woman Writers: Narrating the Ethics of Alterity." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2018. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/210 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEVINAS AND THE NEW WOMAN WRITERS: NARRATING THE ETHICS OF ALTERITY by ANITA TURLINGTON Under the Direction of Leeanne Richardson, PhD ABSTRACT This study applies the ethical theories of Emmanuel Levinas to the novels and short stories of the major New Woman novelists of the fin de siècle in England. Chapter One introduces the study and its theoretical framework. Chapter Two discusses how New Woman writers confront their protagonists with ethical dilemmas framed as face-to-face encounters that can be read as the moment of ethics formation. They also gesture toward openness and indeterminacy through their use of carnivalesque characters. In Chapter Three, Levinas’s concepts of the said and the saying illuminate readings of polemical passages that interrogate the function of language to oppress or empower women. Chapter Four reads dreams, visions, allegories, and proems as mythic references to a golden age past that reframe the idea of feminine altruism. -

Representations, Limitations, and Implications of the “Woman” and Womanhood in Selected Victorian Literature and Contemporary Chick Lit

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University MA in English Theses Department of English Language and Literature 2017 “Not as She is” but as She is Expected to Be: Representations, Limitations, and Implications of the “Woman” and Womanhood in Selected Victorian Literature and Contemporary Chick Lit. Amanda Ellen Bridgers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/english_etd Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Bridgers, Amanda Ellen, "“Not as She is” but as She is Expected to Be: Representations, Limitations, and Implications of the “Woman” and Womanhood in Selected Victorian Literature and Contemporary Chick Lit." (2017). MA in English Theses. 16. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/english_etd/16 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English Language and Literature at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in MA in English Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please see Copyright and Publishing Info. “Not as She is” but as She is Expected to Be: Representations, Limitations, and Implications of the “Woman” and Womanhood in Selected Victorian Literature and Contemporary Chick Lit. by Amanda Bridgers A thesis submitted to the faculty of Gardner-Webb University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English. Boiling Springs, N.C. 2017 ! Bridgers!2! “Not as She is but as She is Expected to Be:’ Representations, Limitations, and Implications of the ‘Woman’ and Womanhood in Selected Victorian Literature and Contemporary Chick Lit.” One face looks out from all his canvases, One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans: We found her hidden just behind those screens, That mirror gave back all her loveliness. -

Download The

GENIUS, WOMANHOOD AND THE STATISTICAL IMAGINARY: 1890s HEREDITY THEORY IN THE BRITISH SOCIAL NOVEL by ZOE GRAY BEAVIS B.A. Hons., La Trobe University, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2014 © Zoe Gray Beavis, 2014 Abstract The central argument of this thesis is that several tropes or motifs exist in social novels of the 1890s which connect them with each other in a genre, and which indicate a significant literary preoccupation with contemporary heredity theory. These tropes include sibling and twin comparison stories, the woman musician’s conflict between professionalism and domesticity, and speculation about biparental inheritance. The particulars of heredity theory with which these novels engage are consistent with the writings of Francis Galton, specifically on hereditary genius and regression theory, sibling and twin biometry, and theoretical population studies. Concurrent with the curiosity of novelists about science, was the anxiety of scientists about discursive linguistic sharing. In the thesis, I illuminate moments when science writers (Galton, August Weismann, William Bates, and Karl Pearson) acknowledged the literary process and the reading audience. I have structured the thesis around the chronological appearance of heredity themes in 1890s social novels, because I am arguing for the existence of a broader cultural curiosity about heredity themes, irrespective of authors’ primary engagement with scientific texts. Finally, I introduce the statistical imaginary as a framework for understanding human difference through populations and time, as evidenced by the construction of theoretical population samples – communities, crowds, and peer groups – in 1890s social fictions. -

Religion & Spirituality in Society Religión Y Espiritualidad En La

IX Congreso Internacional sobre Ninth International Conference on Religión y Religion & Espiritualidad en Spirituality in la Sociedad Society Símbolos religiosos universales: Universal Religious Symbols: Influencias mutuas y relaciones Mutual Influences and Specific específicas Relationships 25–26 de abril de 2019 25–26 April 2019 Universidad de Granada University of Granada Granada, España Granada, Spain La-Religion.com ReligionInSociety.com Centro de Estudios Bizantinos, Neogriegos y Chipriotas Ninth International Conference on Religion & Spirituality in Society “Universal Religious Symbols: Mutual Influences and Specific Relationships” 25–26 April 2019 | University of Granada | Granada, Spain www.ReligionInSociety.com www.facebook.com/ReligionInSociety @religionsociety | #ReligionConference19 IX Congreso Internacional sobre Religión y Espiritualidad en la Sociedad “Símbolos religiosos universales: Influencias mutuas y relaciones específicas” 25–26 de abril de 2019 | Universidad de Granada | Granada, España www.La-Religion.com www.facebook.com/ReligionSociedad @religionsociety | #ReligionConference19 Centro de Estudios Bizantinos, Neogriegos y Chipriotas Ninth International Conference on Religion & Spirituality in Society www.religioninsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please contact [email protected]. Common Ground Research Networks may at times take pictures of plenary sessions, presentation rooms, and conference activities which may be used on Common Ground’s various social media sites or websites. -

Mona Caird's the Daughters of Danaus (1894) As A

UNIVERSITE D’ ANTANANARIVO ECOLE NORMALE SUPERIEURE DEPARTEMENT DE FORMATION INITIALE LITTERAIRE CENTRE D’ETUDE ET DE RECHERCHE EN LANGUE ET LETTRE ANGLAISES MEMOIRE DE CERTIFICAT D’ APTITUDE PEDAGOGIQUE DE L’ ECOLE NORMALE (C.A.P.E.N ) MONA CAIRD’S THE DAUGHTERS OF DANAUS (1894) AS A REFLECTION OF THE EARLY ASPECTS OF FEMINISM IN BRITAIN PRESENTED BY : RAHARIJHON Mbolasoa Nadine DISSERTATION ADVISOR Mrs RABENORO Mireille Date de soutenance : 22 Décembre 2006 ACADEMIC YEAR : 2005-2006 When you accuse me of not being * When you accuse me of not being Like a woman I wonder what like is And how one becomes it I think woman is what Women are And as I am one So must that be included In what woman is So, there fore, I am like by Pat Van Twest. ___________________________________________________________________________ * HEALY, Maura, Women , England, 1984, Longman p. 28 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We address our deep gratitude to : - Mrs RABENORO Mireille, our dissertation advisor, for her precious contribution to the elaboration of this dissertation - Mrs RAZAIARIVELO A. for her advice which were so useful for the achievement of this work. - Mr RAZAFINDRATSIMA E. for he is the one who inspired us the very topic of this dissertation. - Mr Manoro Regis, our teacher and the head of English Department at E.N.S. for his kindness, his patience, and above all his helpful advice. - All our teachers at the English Department of E.N.S. for their support and follow-up while through on the five years’ training. - Our dearest parents and our sister for the kind support they brought to us during all this time. -

John Singer Sargent's British and American Sitters, 1890-1910

JOHN SINGER SARGENT’S BRITISH AND AMERICAN SITTERS, 1890-1910: INTERPRETING CULTURAL IDENTITY WITHIN SOCIETY PORTRAITS EMILY LOUISA MOORE TWO VOLUMES VOLUME 1 PH.D. UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2016 ABSTRACT Began as a compositional analysis of the oil-on-canvas portraits painted by John Singer Sargent, this thesis uses a selection of those images to relate national identity, cultural and social history within cosmopolitan British and American high society between 1890 and 1910. Close readings of a small selection of Sargent’s portraits are used in order to undertake an in-depth analysis on the particular figural details and decorative elements found within these images, and how they can relate to nation-specific ideologies and issues present at the turn of the century. Thorough research was undertaken to understand the prevailing social types and concerns of the period, and biographical data of individual sitters was gathered to draw larger inferences about the prevailing ideologies present in America and Britain during this tumultuous era. Issues present within class and family structures, the institution of marriage, the performance of female identity, and the formulation of masculinity serve as the topics for each of the four chapters. These subjects are interrogated and placed in dialogue with Sargent’s visual representations of his sitters’ identities. Popular images of the era, both contemporary and historic paintings, as well as photographic prints are incorporated within this analysis to fit Sargent’s portraits into a larger art historical context. The Appendices include tables and charts to substantiate claims made in the text about trends and anomalies found within Sargent’s portrait compositions. -

A Complex Legacy of Romanticism in Edith Johnstone's New Woman

Women's Writing ISSN: 0969-9082 (Print) 1747-5848 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwow20 Painting the Soul: A Complex Legacy of Romanticism in Edith Johnstone’s New Woman Novel, A Sunless Heart (1894) Elizabeth Neiman To cite this article: Elizabeth Neiman (2017): Painting the Soul: A Complex Legacy of Romanticism in Edith Johnstone’s New Woman Novel, A Sunless Heart (1894), Women's Writing, DOI: 10.1080/09699082.2017.1334366 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09699082.2017.1334366 Published online: 03 Jun 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rwow20 Download by: [University of Maine - Orono] Date: 03 June 2017, At: 03:43 WOMEN’S WRITING, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/09699082.2017.1334366 PAINTING THE SOUL: A COMPLEX LEGACY OF ROMANTICISM IN EDITH JOHNSTONE’S NEW WOMAN NOVEL, A SUNLESS HEART (1894) Elizabeth Neiman English and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, University of Maine, Orono, Maine, USA ABSTRACT In the last decade of the twentieth century, the scholarly consensus was that genius was incompatible with what Lyn Pykett terms the “proper feminine.” This incompatibility makes the “New Woman” artist-protagonist the exemplar of a genre known for self-conflicted, introspective protagonists. Edith Johnstone’s A Sunless Heart (1894) has been peripheral to this scholarship because Johnstone relegates her artist to the sidelines of a second protagonist’s life. Most New Woman authors recall the narrow brand of Romanticism that reverberates through nineteenth-century poetics—the poet’s lyrical turn inwards to (in John Stuart Mill’s words) “paint the human soul truly.” When Johnstone presents lyricism as an interchange between two people, she seizes what would be an otherwise missed opportunity in New Woman fiction: a portrait of the artist’s struggle not to transpose her subjectivity onto another individual. -

Books at 2016 05 05 for Website.Xlsx

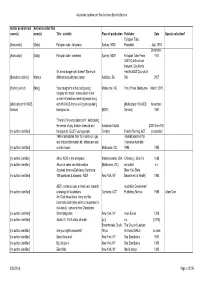

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Book Collection Author or editor last Author or editor first name(s) name(s) Title : sub-title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection? Fallopian Tube [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : fallopiana Sydney, NSW Pamphlet July, 1974 December, [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : madness Sydney, NSW Fallopian Tube Press 1974 GLBTIQ with cancer Network, Gay Men's It's a real bugger isn't it dear? Stories of Health (AIDS Council of [Beresford (editor)] Marcus different sexuality and cancer Adelaide, SA SA) 2007 [Hutton] (editor) [Marg] Your daughter's at the door [poetry] Melbourne, VIC Panic Press, Melbourne March, 1975 Inequity and hope : a discussion of the current information needs of people living [Multicultural HIV/AIDS with HIV/AIDS from non-English speaking [Multicultural HIV/AIDS November, Service] backgrounds [NSW] Service] 1997 "There's 2 in every classroom" : Addressing the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and Australian Capital [2001 from 100 [no author identified] transgender (GLBT) young people Territory Family Planning, ACT yr calendar] 1995 International Year for Tolerance : gay International Year for and lesbian information kit : milestones and Tolerance Australia [no author identified] current issues Melbourne, VIC 1995 1995 [no author identified] About AIDS in the workplace Massachusetts, USA Channing L Bete Co 1988 [no author identified] Abuse in same sex relationships [Melbourne, VIC] not stated n.d. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome : [New York State [no author identified] 100 questions & answers : AIDS New York, NY Department of Health] 1985 AIDS : a time to care, a time to act, towards Australian Government [no author identified] a strategy for Australians Canberra, ACT Publishing Service 1988 Adam Carr And God bless Uncle Harry and his roommate Jack (who we're not supposed to talk about) : cartoons from Christopher [no author identified] Street Magazine New York, NY Avon Books 1978 [no author identified] Apollo 75 : Pix & story, all male [s.l.] s.n. -

New Books on Women & Feminism

NEW BOOKS ON WOMEN & FEMINISM No. 50, Spring 2007 CONTENTS Scope Statement .................. 1 Politics/ Political Theory . 31 Anthropology...................... 1 Psychology ...................... 32 Art/ Architecture/ Photography . 2 Reference/ Bibliography . 33 Biography ........................ 3 Religion/ Spirituality . 34 Economics/ Business/ Work . 6 Science/ Mathematics/ Technology . 37 Education ........................ 8 Sexuality ........................ 37 Film/ Theater...................... 9 Sociology/ Social Issues . 38 Health/ Medicine/ Biology . 10 Sports & Recreation . 44 History.......................... 12 Women’s Movement/ General Women's Studies . 44 Humor.......................... 18 Periodicals ...................... 46 Language/ Linguistics . 18 Index: Authors, Editors, & Translators . 47 Law ............................ 19 Index: Subjects ................... 58 Lesbian Studies .................. 20 Citation Abbreviations . 75 Literature: Drama ................. 20 Literature: Fiction . 21 New Books on Women & Feminism is published by Phyllis Hol- man Weisbard, Women's Studies Librarian for the University of Literature: History & Criticism . 22 Wisconsin System, 430 Memorial Library, 728 State Street, Madi- son, WI 53706. Phone: (608) 263-5754. Email: wiswsl @library.wisc.edu. Editor: Linda Fain. Compilers: Amy Dachen- Literature: Mixed Genres . 25 bach, Nicole Grapentine-Benton, Christine Kuenzle, JoAnne Leh- man, Heather Shimon, Phyllis Holman Weisbard. Graphics: Dan- iel Joe. ISSN 0742-7123. Annual subscriptions are $8.25 for indi- Literature: Poetry . 26 viduals and $15.00 for organizations affiliated with the UW Sys- tem; $16.00 for non-UW individuals and non-profit women's pro- grams in Wisconsin ($30.00 outside the state); and $22.50 for Media .......................... 28 libraries and other organizations in Wisconsin ($55.00 outside the state). Outside the U.S., add $13.00 for surface mail to Canada, Music/ Dance .................... 29 $15.00 elsewhere; or $25.00 for air mail to Canada, $55.00 else- where. -

Author Title Place of Publication Publisher Date Special Collection Wet Leather New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 up Cain

Books Author Title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection Wet leather New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 Up Cain London, United Kingdom Cain of London 197? Up and coming [USA] [s.n.] 197? Welcome to the circus shirkus [Townsville, Qld, Australia] [Student Union, Townsville College of [1978] Advanced Education] A zine about safer spaces, conflict resolution & community [Sydney, NSW, Australia] Cunt Attack and Scumsystemspice 2007 Wimmins TAFE handbook [Melbourne, Vic, Australia] [s.n.] [1993] A woman's historical & feminist tour of Perth [Perth, WA, Australia] [s.n.] nd We are all lesbians : a poetry anthology New York, NY, USA Violet Press 1973 What everyone should know about AIDS South Deerfield, MA, USA Scriptographic Publications Pty Ltd 1992 Victorian State Election 29 November 2014 : HIV/AIDS : What [Melbourne, Vic, Australia] Victorian AIDS Council/Living Positive 2014 your government can do Victoria Feedback : Dixon Hardy, Jerry Davis [USA] [s.n.] c. 1980s Colin Simpson How to increase the size of your penis Sydney, NSW, Australia Venus Publications Pty.Ltd 197? HRC Bulletin, No 72 Canberra, ACT, Australia Humanities Research Centre ANU 1993 It was a riot : Sydney's First Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras Sydney, NSW, Australia 78ers Festival Events Group 1998 Biker brutes New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 Colin Simpson HIV tests and treatments Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia AIDS Council of NSW (ACON) 1997 Fast track New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1980 Colin Simpson Denver University Law Review Denver, CO, -

Consuming Fantasies: Labor, Leisure, and the London Shopgirl

Sanders_FM_3rd.qxp 1/19/2006 10:23 AM Page i CONSUMING FANTASIES Sanders_FM_3rd.qxp 1/19/2006 10:23 AM Page ii Sanders_FM_3rd.qxp 1/19/2006 10:23 AM Page iii Consuming Fantasies: LABOR, LEISURE, AND THE LONDON SHOPGIRL, 1880–1920 Lise Shapiro Sanders The Ohio State University Press Columbus Sanders_FM_3rd.qxp 1/19/2006 10:23 AM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by The Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sanders, Lise, 1970– Consuming fantasies : labor, leisure, and the London shopgirl, 1880–1920 / Lise Shapiro Sanders. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8142-1017-1 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-9093-0 (cd-rom) 1. English literature—19th century—History and criticism. 2. Women sales personnel in literature. 3. English literature—20th centu- ry—History and criticism. 4. Women sales personnel—England— London—History. 5. Working class women—England—London— History. 6. Department stores—England—London—History. 7. Retail trade—England—London—History. 8. Women and literature— England—London. 9. London (England)—In literature. 10. Sex role in literature. I. Title. PR468.W6S26 2006 820.9'3522—dc22 2005029994 Cover design by Jeff Smith. Type set in Adobe Garamond. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Sanders_FM_3rd.qxp 1/19/2006 10:23 AM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1. -

Doctors, Dandies and New Men: Ella Hepworth Dixon and Late-Century Masculinities

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Doctors, Dandies and New Men: Ella Hepworth Dixon and Late-Century Masculinities MacDonald, T. DOI 10.1080/09699082.2012.622980 Publication date 2012 Document Version Final published version Published in Women's Writing Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): MacDonald, T. (2012). Doctors, Dandies and New Men: Ella Hepworth Dixon and Late- Century Masculinities. Women's Writing, 19(1), 41-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/09699082.2012.622980 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:24 Sep 2021 This article was downloaded by: [UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek SZ], [Tara MacDonald] On: 09 February 2012, At: 03:30 Publisher: