Ed 393 216 Author Title Report No Pub Date Available From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nlrcv20201.Pdf

1 2020 Nancy Lipton Rosenblum Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, Emerita Harvard University Department of Government 1731 Cambridge St. Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Educational Background B.A., Radcliffe College, Social Studies, 1969 Ph.D., Harvard University Political Science, 1973 Teaching Positions Chair, Department of Government, Harvard University, 2004-2010 Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, 2001 to 2016 Faculty Fellow, Safra Center for Ethics, Harvard University, 2003-4 Henry Merritt Wriston Professorship, Brown University, 1997- 2001 Chairperson, Political Science Department, Brown University, 1989-95 Professor, Brown University, 1980-2000 Liberal Arts Fellow, Harvard Law School, 1992-93 Fellow, Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, 1988-89 Visiting Professor, Harvard University, Department of Government, Fall, 1985 Associate Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1977-80 Henry LaBarre Jayne Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1973-77 Publications Books A Lot of People are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy”, with Russell Muirhead (Princeton University Press, 2019) 2 Good Neighbors: The Democracy of Everyday Life in America (Princeton University Press, 2016) On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship (Princeton University Press, 2008) Membership and Morals: The Personal Uses of Pluralism in America (Princeton University -

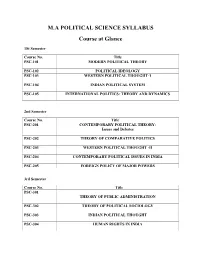

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance 1St Semester Course No. Title PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY PSC-102 POLITICAL IDEOLOGY PSC-103 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT-1 PSC-104 INDIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM PSC-105 INTERNATIONAL POLITICS: THEORY AND DYNAMICS 2nd Semester Course No. Title PSC-201 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THEORY: Issues and Debates PSC-202 THEORY OF COMPARATIVE POLITICS PSC-203 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT -II PSC-204 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL ISSUES IN INDIA PSC-205 FOREIGN POLICY OF MAJOR POWERS 3rd Semester Course No. Title PSC-301 THEORY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PSC-302 THEORY OF POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY PSC-303 INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-304 HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA PSC-305 INDIA IN WORLD AFFAIRS 4th Semester Course No. Title PSC-401 CHANGING DIMENSIONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION IN INDIA PSC-402 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZIATION AND ADMINISTRIATION PSC-403 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY PSC-404 COMPUTER BASICS: THEORY AND PRACTICE Elective CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-405 (i) 405 (ii) LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN INDIA 405 (iii) ETHICS AND POLITICS 405 (iv) COMPARATIVE FEDERALISM 405 (v) SOCIAL EXCLUSION IN INDIA Courses of Studies for M.A. in Political Science (Under Semester System of Teaching & Examination Effective from the Academic Session 2016-17) SEMESTER-I Course No. PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY Unit-I (i) Political Theory- Evolution, The Traditional Approach; Nature and Scope of Traditional Political Theory; Prime Concerns. (ii) Modern Political Theory- Genesis and Evolution; The Modern Behavioural Approach; Nature and Scope of Modern Political Theory; Prime Concerns. Unit-II (i) Political Decision-making Theory of Harold. D. Laswell – The Concept of Politics as the Societal Decision-making Process; Classification of Societal Values; Role of Elites in the Societal Decision-making Process; Effectiveness and Legitimacy of the Societal Decision-making Structure. -

Political Education in the Elementary School: a Decision-Making Rationale

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-6748 COG AN, John Joseph, 1942- POLITICAL EDUCATION IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: A DECISION-MAKING RATIONALE. The Ohio State U niversity, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (£) Copyright by John Joseph Cogan ,1970 POLITICAL EDUCATION IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: A DECISION-MAKING RATIONALE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Joseph Cogan, B.S., M.A, ****** The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by College of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This writer would like to extend hiB appreciation to all who provided guidance and help in any manner during the completion of this study. The writer is indebted immeasurably to his adviser, Professor Raymond H. Muessig, whose patient and continuous counsel made the completion of this study possible. Appreciation is also extended to Professors Robert E. Jewett and Alexander Frazier who served as readers of the dissertation. Finally, the writer is especially grateful to his wife, Norma, and hiB daughter, Susan, whose patience and understanding have been unfailing throughout the course of this study. ii VITA May 30, 19^2 . Born - Youngstown, Ohio 1 9 6 3. B.S., Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 1963-1965.... Elementary Teacher, Columbus Public Schools, Columbus, Ohio I965 ............ M.A., The Ohio State University, ColumbuB, Ohio 1965-1966 .... Graduate Assistant, College of Education, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1966-1967 .... United States Office of Education Fellow, Washington, D.C. Summer, 1967 . Acting Director, Consortium of Professional Associations for the Study of Special Teacher Improvement Programs (CONPASS), Washington, D.C. -

SS 12 Paper V Half 1 Topic 1B

Systems Analysis of David Easton 1 Development of the General Systems Theory (GST) • In early 20 th century the Systems Theory was first applied in Biology by Ludwig Von Bertallanfy. • Then in 1920s Anthropologists Bronislaw Malinowski ( Argonauts of the Western Pacific ) and Radcliffe Brown ( Andaman Islanders ) used this as a theoretical tool for analyzing the behavioural patterns of the primitive tribes. For them it was more important to find out what part a pattern of behaviour in a given social system played in maintaining the system as a whole, rather than how the system had originated. • Logical Positivists like Moritz Schilick, Rudolf Carnap, Otto Von Newrath, Victor Kraft and Herbert Feigl, who used to consider empirically observable and verifiable knowledge as the only valid knowledge had influenced the writings of Herbert Simon and other contemporary political thinkers. • Linguistic Philosophers like TD Weldon ( Vocabulary of Politics ) had rejected all philosophical findings that were beyond sensory verification as meaningless. • Sociologists Robert K Merton and Talcott Parsons for the first time had adopted the Systems Theory in their work. All these developments in the first half of the 20 th century had impacted on the application of the Systems Theory to the study of Political Science. David Easton, Gabriel Almond, G C Powell, Morton Kaplan, Karl Deutsch and other behaviouralists were the pioneers to adopt the Systems Theory for analyzing political phenomena and developing theories in Political Science during late 1950s and 1960s. What is a ‘system’? • Ludwig Von Bertallanfy: A system is “a set of elements standing in inter-action.” • Hall and Fagan: A system is “a set of objects together with relationships between the objects and between their attributes.” • Colin Cherry: The system is “a whole which is compounded of many parts .. -

American Political Science Association

A MERICAN P OLITICAL S CIENCE ASSOCIATION Assessing (In)Security after the Arab Spring John Gledhill, guest editor, April Longley Alley, Brian McQuinn, and Mohammad Ayatollahi Tabaar Misconceptions and Realities of the 2011 Tunisian Election Moez Habadou and Nawel Amrouche Political Science & Politics Katrina Seven Years On PSO CTOBER 2013, V OLUME 46, N UMBER 4 Christine L. Day American Political Science Association Make plans to attend the 2014 APSA Teaching & Learning Conference The 2014 APSA Teaching & Learning Conference theme is “Teaching Inclusively: Inte- grating Multiple Approaches into the Curriculum.” In this unique meeting, APSA strives to promote the greater understanding of cutting- edge approaches, techniques, and methodologies for the political science classroom. Using a working group format, the conference includes plenaries, tracks, and work- shops on topics such as: t Civic Engagement t Integrating Technology in the t Conflict and Conflict Resolution Classroom t Core Curriculum/General t Internationalizing the Curriculum Education t Teaching and Learning at Community t Curricular and Program Assessment Colleges t Distance Learning t Professional Development t Diversity, Inclusiveness, and Equality t Simulations and Role Play t Graduate Education: Teaching and t Teaching Political Theory and Theories Advising Graduate Students t Teaching Research Methods www.apsanet.org/teachingconference 1527 New Hampshire Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036 | 202.483.2512 | www.apsanet.org ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Playstation Blast 16.Pdf

ÍNDICE Pegue a pipoca e vamos além A discussão em torno de jogos cinematográficos não é de hoje, mas parece estar prestes a ganhar um novo foco de debates, o esperado Beyond: Two Souls (PS3). Nós não só preparamos uma Prévia desse grande lançamento, como também trouxemos um Blast from the Past de outra pérola da Quantic Dream: Indigo Prophecy (PS2). E se você acha que a participação de Ellen Page na captura de movimentos de Beyond era um fato extraordinário, nós ainda trazemos um Especial com vários personagens inspirados em personalidades reais. Você confere isso e muito mais sobre os últimos lançamentos da família PlayStation! – Rafael Neves BLAST FROM THETOP PAST 10 ESPECIAL Indigo of Personagens e 04 Prophecy (PS2) suas Inspirações 43 PRÉVIA TOP 5 Beyond Two 5 Jogos da Disney 10 Souls (PS3) para Playstation 47 ANÁLISE ANÁLISE MAIS ONLINE! Persona 3 16 Portable (PSP) Heavy Rain (PS3) ANÁLISE ESPECIAL Killzone: Mercenary Jogos 22 (PSVita) Cinematográficos ANÁLISE PRÉVIA Dragon’s Crown(PS3) Killzone: Shadow 30 Fall (PS4) DISCUSSÃO DISCUSSÃO Jogos Tornam Diversão Deixou de 36 Alguém Violento? Ser Prioridade? playstationblast.com.br 2 / 52 HQ BLAST Os Dramas da Alma por Sybellyus Paiva DIRETOR GERAL / EDITORIAL / PROJETO GRÁFICO Sérgio Estrella DIRETOR DE PAUTAS Rodrigo Estevam DIRETOR DE REVISÃO Alberto Canen DIRETOR DE DIAGRAMAÇÃO Guilherme Vargas REDAÇÃO Thomas Schulze Samuel Coelho Alex Campos Fillipe Salles Rodrigo Estevam Rayner Lacerda Alberto Canen Rafael Neves REVISÃO Vitor Tibério Bruna Lima Rafael Neves Samuel Coelho Ramon de Oliveira José Carlos Alves DIAGRAMAÇÃO David Vieira Lucas Paes Eidy Tasaka Gabriel Leles Breno Madureira Leonardo Correia Ítalo Lourenço Tiffany B. -

Political Science & Politics

Political Science & Politics Volume XXI Number 2 Spring 1988 "/ <£lVE. TbU A MAM WHO 6 RELI&10U5, QUX Cb NO fAhKTlc; A MAM VVHO ^V&RS ^ ro A eo/Mr; /\ MAN WHO LIKES Private Lives and Public Careers Bruce Buchanan, Ronald Elving and Sanford Levinson 1988 Annual Meeting Preview Chatham House Checklist Box One, Chatham, NJ 07928 Telephone: (201) 635-2059 * Arian: Politics in Israel it Ball: Modern Politics and Government 4ed * Cannon and O'Brien: Views from the Bench * Dalton: Citizen Politics in Western Democracies * Dogan and Pelassy: How to Compare Nations * Dolbeare: American Political Thought * Dolbeare: Democracy at Risk rev ed * Dragnich et al.: Politics and Government 2ed •sir Fry: Masters of Public Administration it Godwin: Direct Marketing of Politics * Goodsell: The Case for Bureaucracy 2ed •sir Hancock: West Germany •sir Hancock et al.: Politics in Western Europe ~k Hershey: Running for Office it Hinckley: The Symbolic Presidency * Hood: Tools of Government * Jacobs et al.: Comparative Politics * Jones: The Reagan Legacy * Kaufman: Time, Chance, and Organizations * King: The State in Modern Society it Lynn &. Wildavsky: Public Administration * McFarland: Common Cause * Meehan: The Thinking Game: A Guide to Effective Study * Orren and Polsby: Media and Momentum: New Hampshire * Peters: American Public Policy 2ed •sir Rose: The Post-Modern Presidency * Sartori: The Theory of Democracy Revisited * Savas: Privatization: The Key to Better Government * Wilson: Business and Politics * Published it Forthcoming On your request for exam copies, please state course title, present text, and enrollment on your letterhead and send it to Edward Artinian, publisher, Chatham House Publishers, Inc., Box One, Chatham, New Jersey 07928 or telephone (201) 635-2059. -

Chris Riddell

84 Greville Road, Cambridge, Chris Cambridgeshire, CB1 3QL Mobile: +44 (0)7395 484351 Riddell E-Mail: [email protected] Portfolio: www.axisphere.art -3D Artist- Profile As a highly motivated and self-taught CG artist I have always pushed the industries current tools to produce real-time art work of the upmost quality. Being interested in game engines, I have always enjoyed working with cutting edge technology to push the envelope of real- time graphics. I continue to provide creative input into producing some of the industry's best tools and rendering technology to produce work of excellent merit. As a keen learner and avid tech fanatic I always seek and pursue innovation. Experience Virtual Arts Limited 2017 - Present - Principal Artist/Tech Art I joined a new startup in Cambridge for a fresh challenge in Mobile VR/AR. My role at Virtual Arts Limited is creating shader networks, Unity tech art, content creation, inputting into creating our own engine/tool pipeline and to schedule artwork. Sony Interactive Entertainment 2004-2017 - Principal Artist I joined SCEE/SIE as a standard level artist and progressed to principal level. My 13-year period saw a lot of projects with some very challenging situations creating games for brand new platforms/technology, the toughest challenge being to create a Virtual Reality title (RIGS) which would be fast paced without creating nausea and achieve a solid 60 FPS throughout the experience. In my career at Sony I’ve inputted into developing our internal engines and tools, create 2D/3D graphics for our products, produce basic concept art to focus prototypes for future projects, write technical documentation and tutorials to educate the art team, worked closely with marketing to provide resources to advertise and create online social media presence, entertained VIP visitors, and educated myself in legal issues regarding design and copyright issues. -

Foundation of Political Science

School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION I SEMESTER B.A POLITICAL SCIENCE (2013 ADMISSION) CORE COURSE FOUNDATION OF POLITICAL SCIENCE QUESTION BANK 1. Who defined political science is “that part of social science which treats the foundations of the foundations of the state and principles of government”? a. Paul Janet; b. Dyke; c. Gettell; d. None of it 2. Who is the author of “A History of Political Theory”? a. Karl Popper; b. Sabine; c. Mill; d. Locke 3. Who described historical approach as ‘historicism’? a. Bentham; b. Hegel; c. Popper; d. Marx 4. Which approach is, according to Rober A Dahl, an attempt to make the empirical content of Political Science more scientific “ a. Institutional Approach c. Philosophical Approach b. Historical Approach d. Behavioural Approach 5. Who introduced ‘intellectual foundations’ for behavioural approach? a. Easton; b. Merriam; c. Lasswell; d. Bentley 6. Who said “the concept of power is the most fundamental in the whole of Political Science: the Political Process is the shaping, dissolution and exercise of power” ? a. Merriam and Easton c. Catlin and Bentley b. Lasswell and Kaplan d. None of them 7. Who is known as the greatest advocate of Post-Behaviouralism? a. Merriam; b. Easton; c. Lasswell; d. Bentley 8. Which approach demands ‘relevance’ and ‘action’? a. Institutional Approach c. Behaviouralist b. Post-Behaviouralist Approach d. Historical Approach 9. Whose definition encompasses the ‘politics of consent’ as well as the ‘politics of struggle’? a. Easton; b. Merriam; c. Lasswell; d. Kaplan 10. Who introduced ‘politics of consent’ ? a. Lasswell; b. -

Gaikai - Wikipedia Case 3:19-Cv-07027-WHA Document 28-2 Filed 10/14/19 Page 2 of 8 Not Logged in Talk Contributions Create Account Log In

Case 3:19-cv-07027-WHA Document 28-2 Filed 10/14/19 Page 1 of 8 EXHIBIT B Gaikai - Wikipedia Case 3:19-cv-07027-WHA Document 28-2 Filed 10/14/19 Page 2 of 8 Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Gaikai From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Gaikai (外海, lit. "open sea", i.e. an expansive outdoor space) is an American company which provides technology for the streaming of high- Contents Gaikai Featured content end video games.[1] Founded in 2008, it was acquired by Sony Interactive Entertainment in 2012. Its technology has multiple applications, Current events including in-home streaming over a local wired or wireless network (as in Remote Play between the PlayStation 4 and PlayStation Vita), as Random article well as cloud-based gaming where video games are rendered on remote servers and delivered to end users via internet streaming (such as Donate to Wikipedia the PlayStation Now game streaming service.[2]) As a startup, before its acquisition by Sony, the company announced many partners using Wikipedia store [3] the technology from 2010 through 2012 including game publishers, web portals, retailers and consumer electronics manufacturers. On July Founded November 2008 Interaction 2, 2012, Sony announced that a formal agreement had been reached to acquire the company for $380 million USD with plans of establishing Headquarters Aliso Viejo, California, U.S. [4] Help their own new cloud-based gaming service, as well as integrating streaming technology built by Gaikai into PlayStation products, resulting Owner Sony [5] [6] About Wikipedia in PlayStation Now and Remote Play. -

Scott L. Althaus

Althaus – 1 SCOTT L. ALTHAUS Cline Center for Advanced Social Research Office: 217.265.7845 University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign Fax: 217.265.7880 2001 South First St., Suite 207 E‐mail: [email protected] Champaign, IL 61820‐7461 Web: www.illinois.edu/~salthaus CURRENT APPOINTMENTS Merriam Professor of Political Science and Professor of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign (2012‐present). Director of the Cline Center for Advanced Social Research, University of Illinois at Urbana‐ Champaign (2014‐present) Faculty Affiliate of the following University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign units: School of Information Sciences (2016‐present) National Center for Supercomputer Applications (2014‐present) Institute for Computing in the Humanities and Social Sciences (2014‐present) Illinois Informatics Institute (2011‐present) PAST APPOINTMENTS Associate Director of the Cline Center for Democracy, University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign (2011‐2014) Associate Professor, Department of Political Science and Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign (2003‐2012). Assistant Professor, Department of Communication and Department of Political Science, University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign (1996‐2003). EDUCATION NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Ph.D. in Political Science with certificate in Political Communication, December 1996. M.A. in Political Science, June 1993. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY B.A. in Rhetoric with honors, May 1991. Departmental honors, Phi Beta Kappa. DIABLO VALLEY COLLEGE, PLEASANT HILL, CA General education studies, 1987‐89. BOOKS Althaus, Scott. In preparation. Time in the Fight: Understanding Popular Support for America’s Wars. Under contract with Cambridge University Press. Althaus, Scott. 2003. Collective Preferences in Democratic Politics: Opinion Surveys and the Will of the People. -

1 a Theoretical Framework for Exploring

A theoretical framework for exploring the capability of participative and collective governance in sustainable outcomes - Literature Review and Draft Framework- Jennifer Meyer-Ueding Division of Cooperative Sciences, Department of Agricultural Economics, Humboldt University of Berlin, [email protected] Abstract This paper presents the draft of a composite theoretical framework for describing participative and collective forms of resource governance in integrative institutional settings. Given the observable deficiencies in hierarchical governance, the underlying approach argues that the transfer of governance powers to affected stakeholders makes the provision of basic and limited resources more legitimate and sustainable as long as it is organized according to specific criteria for participation and cooperation. Our approach is multidisciplinary, combining insights from political science, institutional economics and systems theory in an extensive literature review. This draft framework is intended for analyzing the degree of participative governance and collective action according to appropriate organizational forms of civil society at the local level and in an urban context in India (i.e. cooperatives, NGOs, CBOs) but can be employed for analyzing different organizational forms at different levels (local, regional, national, global). Key words: Framework, Participative Governance, Collective Action, Social Capital, Sustainable Development, Integrative Institutions, Civil Society, System Theory, Actor- Centered Institutionalism, India, Hyderabad 1. Aims and scope of this paper This paper aims to design a comprehensive framework to aid both in the analysis of the degree of participative governance and collective action according to appropriate organizational forms and at various levels, and to analyse its implications for sustainability. It is intended to deliver some new insights into the interrelation between participation, collective action and sustainability.