Deliberative Polling As the Gold Standard Jane Mansbridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analyzing Change in International Politics: the New Institutionalism and the Interpretative Approach

Analyzing Change in International Politics: The New Institutionalism and the Interpretative Approach - Guest Lecture - Peter J. Katzenstein* 90/10 This discussion paper was presented as a guest lecture at the MPI für Gesellschaftsforschung, Köln, on April 5, 1990 Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung Lothringer Str. 78 D-5000 Köln 1 Federal Republic of Germany MPIFG Discussion Paper 90/10 Telephone 0221/ 336050 ISSN 0933-5668 Fax 0221/ 3360555 November 1990 * Prof. Peter J. Katzenstein, Cornell University, Department of Government, McGraw Hall, Ithaca, N.Y. 14853, USA 2 MPIFG Discussion Paper 90/10 Abstract This paper argues that realism misinterprets change in the international system. Realism conceives of states as actors and international regimes as variables that affect national strategies. Alternatively, we can think of states as structures and regimes as part of the overall context in which interests are defined. States conceived as structures offer rich insights into the causes and consequences of international politics. And regimes conceived as a context in which interests are defined offer a broad perspective of the interaction between norms and interests in international politics. The paper concludes by suggesting that it may be time to forego an exclusive reliance on the Euro-centric, Western state system for the derivation of analytical categories. Instead we may benefit also from studying the historical experi- ence of Asian empires while developing analytical categories which may be useful for the analysis of current international developments. ***** In diesem Aufsatz wird argumentiert, daß der "realistische" Ansatz außenpo- litischer Theorie Wandel im internationalen System fehlinterpretiere. Dieser versteht Staaten als Akteure und internationale Regime als Variablen, die nationale Strategien beeinflussen. -

Ed 393 216 Author Title Report No Pub Date Available From

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 216 EA 027 482 AUTHOR Scribner, Jay D., Ed.; Layton, Donald H., Ed. TITLE The Study of Educational Politics. 1994 Commemorative Yearbook of the Politics of Education Association (1969-1994). Education Policy Perspectives Series. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7507-0419-5 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 225p. AVAILABLE FROM Falmer Press, Taylor & Francis, Inc., 1900 Frost Road, Suite 101, Bristol, PA 19007 (paperback: ISBN-0-7507-0419-5; clothbound: ISBN-0-7507-0418-7). PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Principles; Educational Sociology; Elementary Secondary Education; Feminism; Ideology; International Education; *Policy Analysis; *Policy Formation; Political Influences; *Politics of Education; Role of Education; Values ABSTRACT This book surveys major trends in the politics of education over the last 25 years. Chapters synthesize political and policy developments at local, national, and state levels in the United States, as well as in the international arena. The chapters examine the emerging micropolitics of education and policy-analysis, cultural, and feminist studies. The foreword is by Paul E. Peterson and the introduction by Jay D. Scribner and Donald H.Layton. Chapters include:(1) "Values: The 'What?' of the Politics of Education" (Robert T. Stout, Marilyn Tallerico, and Kent Paredes Scribner) ;(2) "The Politics of Education: From Political Science to Interdisciplinary Inquiry" (Kenneth K. Wong);(3) "The Crucible of Democracy: The Local Arena" (Laurence Iannaccone and Frank W.Lutz); (4) "State Policymaking and School Reform: Influences and Influentials" (Tim L. Mazzoni);(5) "Politics of Education at the Federal Level" (Gerald E. Sroufe) ;(6) "The International Arena: The Global Village" (Frances C. -

The Politics of Group Representation Quotas for Women and Minorities Worldwide Mona Lena Krook and Diana Z

The Politics of Group Representation Quotas for Women and Minorities Worldwide Mona Lena Krook and Diana Z. O’Brien In recent years a growing number of countries have established quotas to increase the representation of women and minorities in electoral politics. Policies for women exist in more than one hundred countries. Individual political parties have adopted many of these provisions, but more than half involve legal or constitutional reforms requiring that all parties select a certain proportion of female candidates.1 Policies for minorities are present in more than thirty countries.2 These measures typically set aside seats that other groups are ineligible to contest. Despite parallels in their forms and goals, empirical studies on quotas for each group have developed largely in iso- lation from one another. The absence of comparative analysis is striking, given that many normative arguments address women and minorities together. Further, scholars often generalize from the experiences of one group to make claims about the other. The intuition behind these analogies is that women and minorities have been similarly excluded based on ascriptive characteristics like sex and ethnicity. Concerned that these dynamics undermine basic democratic values of inclusion, many argue that the participation of these groups should be actively promoted as a means to reverse these historical trends. This article examines these assumptions to explore their leverage in explaining the quota policies implemented in national parliaments around the world. It begins by out- lining three normative arguments to justify such measures, which are transformed into three hypotheses for empirical investigation: (1) both women and minorities will re- ceive representational guarantees, (2) women or minorities will receive guarantees, and (3) women will receive guarantees in some countries, while minorities will receive them in others. -

Rethinking Representation Author(S): Jane Mansbridge Source: the American Political Science Review, Vol

Rethinking Representation Author(s): Jane Mansbridge Source: The American Political Science Review, Vol. 97, No. 4 (Nov., 2003), pp. 515-528 Published by: American Political Science Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3593021 . Accessed: 16/08/2013 04:49 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Political Science Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 88.119.17.198 on Fri, 16 Aug 2013 04:49:00 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions American Political Science Review Vol. 97, No. 4 November 2003 Rethinking Representation JANE MANSBRIDGE Harvard University long withthe traditional"promissory" form of representation,empirical political scientists have recently analyzed several new forms, called here "anticipatory,""gyroscopic," and "surrogate" representation. None of these more recently recognized forms meets the criteria for democratic accountability developed for promissory representation, yet each generates a set of normative criteria by which it can be judged. These criteria are systemic, in contrast to the dyadic criteria appropriate for promissory representation. They are deliberative rather than aggregative. -

Theda Skocpol

NAMING THE PROBLEM What It Will Take to Counter Extremism and Engage Americans in the Fight against Global Warming Theda Skocpol Harvard University January 2013 Prepared for the Symposium on THE POLITICS OF AMERICA’S FIGHT AGAINST GLOBAL WARMING Co-sponsored by the Columbia School of Journalism and the Scholars Strategy Network February 14, 2013, 4-6 pm Tsai Auditorium, Harvard University CONTENTS Making Sense of the Cap and Trade Failure Beyond Easy Answers Did the Economic Downturn Do It? Did Obama Fail to Lead? An Anatomy of Two Reform Campaigns A Regulated Market Approach to Health Reform Harnessing Market Forces to Mitigate Global Warming New Investments in Coalition-Building and Political Capabilities HCAN on the Left Edge of the Possible Climate Reformers Invest in Insider Bargains and Media Ads Outflanked by Extremists The Roots of GOP Opposition Climate Change Denial The Pivotal Battle for Public Opinion in 2006 and 2007 The Tea Party Seals the Deal ii What Can Be Learned? Environmentalists Diagnose the Causes of Death Where Should Philanthropic Money Go? The Politics Next Time Yearning for an Easy Way New Kinds of Insider Deals? Are Market Forces Enough? What Kind of Politics? Using Policy Goals to Build a Broader Coalition The Challenge Named iii “I can’t work on a problem if I cannot name it.” The complaint was registered gently, almost as a musing after-thought at the end of a June 2012 interview I conducted by telephone with one of the nation’s prominent environmental leaders. My interlocutor had played a major role in efforts to get Congress to pass “cap and trade” legislation during 2009 and 2010. -

Nlrcv20201.Pdf

1 2020 Nancy Lipton Rosenblum Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, Emerita Harvard University Department of Government 1731 Cambridge St. Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Educational Background B.A., Radcliffe College, Social Studies, 1969 Ph.D., Harvard University Political Science, 1973 Teaching Positions Chair, Department of Government, Harvard University, 2004-2010 Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, 2001 to 2016 Faculty Fellow, Safra Center for Ethics, Harvard University, 2003-4 Henry Merritt Wriston Professorship, Brown University, 1997- 2001 Chairperson, Political Science Department, Brown University, 1989-95 Professor, Brown University, 1980-2000 Liberal Arts Fellow, Harvard Law School, 1992-93 Fellow, Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, 1988-89 Visiting Professor, Harvard University, Department of Government, Fall, 1985 Associate Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1977-80 Henry LaBarre Jayne Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1973-77 Publications Books A Lot of People are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy”, with Russell Muirhead (Princeton University Press, 2019) 2 Good Neighbors: The Democracy of Everyday Life in America (Princeton University Press, 2016) On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship (Princeton University Press, 2008) Membership and Morals: The Personal Uses of Pluralism in America (Princeton University -

Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar

The Profession ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar Michael Peress, SUNY–Stony Brook ABSTRACT This article develops a number of measures of the research productivity of politi- cal science departments using data collected from Google Scholar. Departments are ranked in terms of citations to articles published by faculty, citations to articles recently published by faculty, impact factors of journals in which faculty published, and number of top pub- lications in which faculty published. Results are presented in aggregate terms and on a per-faculty basis. he most widely used measure of the quality of of search results, from which I identified publications authored political science departments is the US News and by that faculty member, the journal in which the publication World Report ranking. It is based on a survey sent appeared (if applicable), and the number of citations to that to political science department heads and direc- article or book. tors of graduate studies. Respondents are asked to I constructed four measures for each faculty member. First, Trate other political science departments on a 1-to-5 scale; their I calculated the total number of citations. This can be -

Review Article the MANY VOICES of POLITICAL CULTURE Assessing Different Approaches

Review Article THE MANY VOICES OF POLITICAL CULTURE Assessing Different Approaches By RICHARD W. WILSON Richard J. Ellis and Michael Thompson, eds. Culture Matters: Essays in Honor of Aaron Wildavsky. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1997, 252 pp. Michael Gross. Ethics and Activism: The Theory and Practice of Political Moral- ity. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997, 305 pp. Samuel P. Huntington. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996, 367 pp. Ronald Inglehart. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic and Political Change in Forty-three Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997, 453 pp. David I. Kertzer. Politics and Symbols:The Italian Communist Party and the Fall of Communism. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996, 211 pp. HE popularity of political culture has waxed and waned, yet it re- Tmains an enduring feature of political studies. In recent years the appearance of many excellent books and articles has reminded us of the timeless appeal of the subject and of the need in political analysis to ac- count for values and beliefs. To what extent, though, does the current batch of studies in political culture suffer from the difficulties that plagued those of an earlier time? The recent resurgence of interest in political culture suggests the importance of assessing the relative merits of the different approaches that theorists employ. ESTABLISHING EVALUATIVE CRITERIA The earliest definitions of political culture noted the embedding of po- litical systems in sets of meanings and purposes, specifically in symbols, myths, beliefs, and values.1 Pye later enlarged upon this theme, stating 1 Sidney Verba, “Comparative Political Culture,” in Lucian W. -

Theda Skocpol | Mershon Center for International Security Studies | the Ohio State Univ

Theda Skocpol | Mershon Center for International Security Studies | The Ohio State Univ... Page 1 of 2 The Ohio State University www.osu.edu Help Campus map Find people Webmail Search home > events calendar > september 2006 > theda skocpol September Citizenship Lecture Series October Theda Skocpol November December "Voice and Inequality: The Transformation of American Civic Democracy" January Theda Skocpol Professor of Government February Monday, Sept. 25, 2006 and Sociology March Noon Dean of the Graduate Mershon Center for International Security Studies April School of Arts and 1501 Neil Ave., Columbus, OH 43201 Sciences May Harvard University 2007-08 See a streaming video of this lecture. This streaming video requires RealPlayer. If you do not have RealPlayer, you can download it free. Theda Skocpol is the Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology and Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. She has also served as Director of the Center for American Political Studies at Harvard from 1999 to 2006. The author of nine books, nine edited collections, and more than seven dozen articles, Skocpol is one of the most cited and widely influential scholars in the modern social sciences. Her work has contributed to the study of comparative politics, American politics, comparative and historical sociology, U.S. history, and the study of public policy. Her first book, States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China (Cambridge, 1979), won the 1979 C. Wright Mills Award and the 1980 American Sociological Association Award for a Distinguished Contribution to Scholarship. Her Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States (Harvard, 1992), won five scholarly awards. -

Coming in the NEXT ISSUE

Association News contributors to the international scientific DBASSE can be accessed at http://sites. community. Nearly 500 members of the nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/index. Coming NAS have won Nobel Prizes” (See http:// htm. Presiding over DBASSE presently nasonline.org/about-nas/mission). is political scientist Kenneth Prewitt. in the For the past century and a half, mem- Scholars who are not NAS members also NEXT bers have investigated and responded to regularly participate as members of NAS questions posed by our national leaders committees, and we urge all political sci- ISSUE as a form of service to the nation without entists to give serious consideration to financial recompense. As Ralph Cicerone, these requests. A preview of some of the articles in the president of the NAS, never fails to relate The discussion at this year’s meeting April 2014 issue: to new members at the annual installation of NAS-member political scientists at ceremony, while our advice is often solic- the APSA convention centered on how to SYMPOSIUM ited—its first report to the Lincoln admin- effectively transmit the best social science US PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION istration addressed whether our country knowledge to the government through FORECASTING should adopt the metric system, and sent the NRC. One issue facing the NRC in Michael Lewis-Beck and back a consensus “yes” answer—this ad- general and the DBASSE in particular Mary Stegmaier, guest editors vice is not always followed. Scientific is that by charter the NAS is not permit- FEATURES objectivity is the goal of the Academy, not ted to solicit contracts from government political advocacy. -

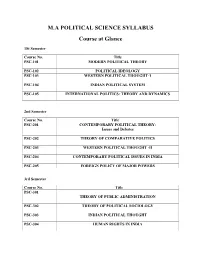

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance 1St Semester Course No. Title PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY PSC-102 POLITICAL IDEOLOGY PSC-103 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT-1 PSC-104 INDIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM PSC-105 INTERNATIONAL POLITICS: THEORY AND DYNAMICS 2nd Semester Course No. Title PSC-201 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THEORY: Issues and Debates PSC-202 THEORY OF COMPARATIVE POLITICS PSC-203 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT -II PSC-204 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL ISSUES IN INDIA PSC-205 FOREIGN POLICY OF MAJOR POWERS 3rd Semester Course No. Title PSC-301 THEORY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PSC-302 THEORY OF POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY PSC-303 INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-304 HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA PSC-305 INDIA IN WORLD AFFAIRS 4th Semester Course No. Title PSC-401 CHANGING DIMENSIONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION IN INDIA PSC-402 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZIATION AND ADMINISTRIATION PSC-403 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY PSC-404 COMPUTER BASICS: THEORY AND PRACTICE Elective CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-405 (i) 405 (ii) LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN INDIA 405 (iii) ETHICS AND POLITICS 405 (iv) COMPARATIVE FEDERALISM 405 (v) SOCIAL EXCLUSION IN INDIA Courses of Studies for M.A. in Political Science (Under Semester System of Teaching & Examination Effective from the Academic Session 2016-17) SEMESTER-I Course No. PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY Unit-I (i) Political Theory- Evolution, The Traditional Approach; Nature and Scope of Traditional Political Theory; Prime Concerns. (ii) Modern Political Theory- Genesis and Evolution; The Modern Behavioural Approach; Nature and Scope of Modern Political Theory; Prime Concerns. Unit-II (i) Political Decision-making Theory of Harold. D. Laswell – The Concept of Politics as the Societal Decision-making Process; Classification of Societal Values; Role of Elites in the Societal Decision-making Process; Effectiveness and Legitimacy of the Societal Decision-making Structure. -

Political Education in the Elementary School: a Decision-Making Rationale

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-6748 COG AN, John Joseph, 1942- POLITICAL EDUCATION IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: A DECISION-MAKING RATIONALE. The Ohio State U niversity, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (£) Copyright by John Joseph Cogan ,1970 POLITICAL EDUCATION IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: A DECISION-MAKING RATIONALE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Joseph Cogan, B.S., M.A, ****** The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by College of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This writer would like to extend hiB appreciation to all who provided guidance and help in any manner during the completion of this study. The writer is indebted immeasurably to his adviser, Professor Raymond H. Muessig, whose patient and continuous counsel made the completion of this study possible. Appreciation is also extended to Professors Robert E. Jewett and Alexander Frazier who served as readers of the dissertation. Finally, the writer is especially grateful to his wife, Norma, and hiB daughter, Susan, whose patience and understanding have been unfailing throughout the course of this study. ii VITA May 30, 19^2 . Born - Youngstown, Ohio 1 9 6 3. B.S., Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 1963-1965.... Elementary Teacher, Columbus Public Schools, Columbus, Ohio I965 ............ M.A., The Ohio State University, ColumbuB, Ohio 1965-1966 .... Graduate Assistant, College of Education, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1966-1967 .... United States Office of Education Fellow, Washington, D.C. Summer, 1967 . Acting Director, Consortium of Professional Associations for the Study of Special Teacher Improvement Programs (CONPASS), Washington, D.C.