Political Education in the Elementary School: a Decision-Making Rationale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed 393 216 Author Title Report No Pub Date Available From

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 216 EA 027 482 AUTHOR Scribner, Jay D., Ed.; Layton, Donald H., Ed. TITLE The Study of Educational Politics. 1994 Commemorative Yearbook of the Politics of Education Association (1969-1994). Education Policy Perspectives Series. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7507-0419-5 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 225p. AVAILABLE FROM Falmer Press, Taylor & Francis, Inc., 1900 Frost Road, Suite 101, Bristol, PA 19007 (paperback: ISBN-0-7507-0419-5; clothbound: ISBN-0-7507-0418-7). PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Principles; Educational Sociology; Elementary Secondary Education; Feminism; Ideology; International Education; *Policy Analysis; *Policy Formation; Political Influences; *Politics of Education; Role of Education; Values ABSTRACT This book surveys major trends in the politics of education over the last 25 years. Chapters synthesize political and policy developments at local, national, and state levels in the United States, as well as in the international arena. The chapters examine the emerging micropolitics of education and policy-analysis, cultural, and feminist studies. The foreword is by Paul E. Peterson and the introduction by Jay D. Scribner and Donald H.Layton. Chapters include:(1) "Values: The 'What?' of the Politics of Education" (Robert T. Stout, Marilyn Tallerico, and Kent Paredes Scribner) ;(2) "The Politics of Education: From Political Science to Interdisciplinary Inquiry" (Kenneth K. Wong);(3) "The Crucible of Democracy: The Local Arena" (Laurence Iannaccone and Frank W.Lutz); (4) "State Policymaking and School Reform: Influences and Influentials" (Tim L. Mazzoni);(5) "Politics of Education at the Federal Level" (Gerald E. Sroufe) ;(6) "The International Arena: The Global Village" (Frances C. -

Comparative Government

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Fall 9-1-2001 PSC 520.01: Comparative Government Louis Hayes University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hayes, Louis, "PSC 520.01: Comparative Government" (2001). Syllabi. 7024. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/7024 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political Science 520 COMPARATIVE POLITICS 9/13 Comparative Government and Political Science Robert A Dahl, "Epitaph for a Monument to a Successful Protest, "AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW 1961 763-72 -------------------- ---- ----- 9/20 Systems Approach David Easton, "An Approach to the Analysis of Political Systems," WORLD POLITICS (April 1957) 383-400 Gabriel Almond _and G. Bingham Powell, COMPARATIVE POLITICS: A DEVEtOPMENTAL APPROACH, Chapter II 9/27 Structural-functional Analysis William Flanigan and Edwin Fogelman, "Functionalism in Political Science," in Don Martindale, ed. , FUNCTIONALISM IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES 111-126 Robert Holt, "A Proposed Structural-Functional Framework for Political Science," in Martindale, 84-110 10/4 Political Legitimacy and Authority Richard Lowenthal, "Political Legitimacy and Cultural Change in West and East" SOCIAL RESEARCH (Autumn 1979), 401-35 Young Kim, "Authority: - Some Conceptual and Empirical Notes" Western Political Quarterly (June 1966), 223-34 10/11 Political Parties and Groups Steven Reed, "Structure and Behavior: Extending Duverger's Law to the Japanese Case," British Journal of Political Science (July 1999) 335-56. -

Nlrcv20201.Pdf

1 2020 Nancy Lipton Rosenblum Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, Emerita Harvard University Department of Government 1731 Cambridge St. Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Educational Background B.A., Radcliffe College, Social Studies, 1969 Ph.D., Harvard University Political Science, 1973 Teaching Positions Chair, Department of Government, Harvard University, 2004-2010 Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, 2001 to 2016 Faculty Fellow, Safra Center for Ethics, Harvard University, 2003-4 Henry Merritt Wriston Professorship, Brown University, 1997- 2001 Chairperson, Political Science Department, Brown University, 1989-95 Professor, Brown University, 1980-2000 Liberal Arts Fellow, Harvard Law School, 1992-93 Fellow, Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, 1988-89 Visiting Professor, Harvard University, Department of Government, Fall, 1985 Associate Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1977-80 Henry LaBarre Jayne Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1973-77 Publications Books A Lot of People are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy”, with Russell Muirhead (Princeton University Press, 2019) 2 Good Neighbors: The Democracy of Everyday Life in America (Princeton University Press, 2016) On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship (Princeton University Press, 2008) Membership and Morals: The Personal Uses of Pluralism in America (Princeton University -

"The New Non-Science of Politics: on Turns to History in Polltical Sciencen

"The New Non-Science of Politics: On Turns to History in Polltical Sciencen Rogers Smith CSST Working CRSO Working Paper #59 Paper #449 October 1990 The New Non-Science of Politics : On Turns to Historv in Political Science Prepared for the CSST Conference on "The Historic Turn in the Human Sciences" Oct. 5-7, 1990 Ann Arbor, Michigan Rogers M. Smith Department of Political Science Yale University August, 1990 The New Non-Science of Po1itic.s Rogers M. Smit-h Yale University I. Introducticn. The canon of major writings on politics includes a considerable number that claim to offer a new science of politics, or a new science of man that encompasses politics. Arlc,totle, Hobbos, Hume, Publius, Con~te,Bentham, Hegel, Marx, Spencer, Burgess, Bentley, Truman, East.on, and Riker are amongst the many who have clairr,ed, more or less directly, that they arc founding or helping to found a true palitical science for the first tlme; and the rccent writcrs lean heavily on the tcrni "science. "1 Yet very recently, sorno of us assigned the title "political scien:iSt" havc been ti-il-ning returning to act.ivities that many political scientist.^, among others, regard as unscientific--to the study of instituti~ns, usually in historical perspective, and to historica! ~a'lternsand processes more broadly. Some excellent scholars belie-ve this turn is a disast.er. It has been t.ernlod a "grab bag of diverse, often conf!icting approaches" that does not offer anything iike a scientific theory (~kubband Moe, 1990, p. 565) .2 In this essay I will argue that the turn or return t.o institutions and history is a reasonable response to two linked sets of probicms. -

Political Development Theory in the Sociological and Political Analyses of the New States

POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT THEORY IN THE SOCIOLOGICAL AND POLITICAL ANALYSES OF THE NEW STATES by ROBERT HARRY JACKSON B.A., University of British Columbia, 1964 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Political Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, I966 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission.for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Polit_i_g^j;_s_gience The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date September, 2, 1966 ii ABSTRACT The emergence since World War II of many new states in Asia and Africa has stimulated a renewed interest of sociology and political science in the non-western social and political process and an enhanced concern with the problem of political development in these areas. The source of contemporary concepts of political development can be located in the ideas of the social philosophers of the nineteenth century. Maine, Toennies, Durkheim, and Weber were the first social observers to deal with the phenomena of social and political development in a rigorously analytical manner and their analyses provided contemporary political development theorists with seminal ideas that led to the identification of the major properties of the developed political condition. -

Civic Culture

1 Civic Culture Civic culture is a set of political attitudes, habits, sentiments and behaviour related to the functioning of the democratic regime. It implies that although citizens are not necessarily involved in politics all the time, they are aware to a certain extent of their political rights and also of the implications of the decision making process that affects their life and society. Both political awareness and participation are supposed to be relevant to the stability of a political regime. By contrast citizens´ withdraw from political life has consequences not only for their ability to get what they want from the political community, but also for the quality of democracy. Civic culture involves, therefore, some level of perception of the republican character of modern politics, and adds a psychological dimension to the concept of citizenship. The concept of civic culture is part of a long tradition of thought that investigates the nature of democracy from a historical perspective. It refers to the role of political tradition, values and culture for the achievement of democratization and the stabilization of a regime. Its rationale goes back to the thinking of ancient political philosophers such as Aristotle, but in modern and contemporary times also Machiavelli, Montesquieu, Tocqueville, J. S. Mill, Weber and Bobbio, among others, have discussed whether a set of specific political attitudes, convictions and behaviour are a necessary and/or sufficient condition for the success of modern democracies. The question is controversial, but it has never disappeared from the debate about the necessary conditions to achieve the “good government”, e.g., a political regime committed to the ideal of full human realization. -

Giving Hands and Feet to Morality

Perspectives Forum on the Chicago School of Political Science Giving Hands and Feet to Morality By Michael Neblo f you look closely at the stone engraving that names the Social the increasing sense of human dignity on the other, makes possible a Science Research building at the University of Chicago, you far more intelligent form of government than ever before in history.2 Ican see a curious patch after the e in Science. Legend has it the By highlighting their debt to pragmatism and progressivism, I patch covers an s that Robert Maynard Hutchins ordered do not mean to diminish Merriam’s and Lasswell’s accom- stricken; there is only one social science, Hutchins insisted. plishments, but only to situate and explain them in a way con- I do not know whether the legend is true, but it casts in an gruent with these innovators’ original motivations. Merriam interesting light the late Gabriel Almond’s critique of intended the techniques of behavioral political science to aug- Hutchins for “losing” the ment and more fully realize Chicago school of political the aims of “traditional” polit- science.1 Lamenting the loss, Political science did not so much “lose” the ical science—what we would Almond tries to explain the now call political theory. rise of behavioral political sci- Chicago school as walk away from it. Lasswell agreed, noting that ence at Chicago and its subse- the aim of the behavioral sci- quent fall into institutional entist “is nothing less than to give hands and feet to morality.”3 neglect. Ironically, given the topic, he alights on ideographic Lasswell’s protégé, a young Gabriel Almond, went even explanations for both phenomena, locating them in the per- further: sons of Charles Merriam and Hutchins, respectively. -

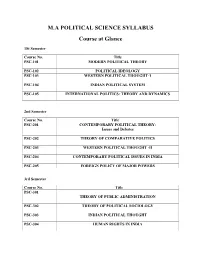

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance 1St Semester Course No. Title PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY PSC-102 POLITICAL IDEOLOGY PSC-103 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT-1 PSC-104 INDIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM PSC-105 INTERNATIONAL POLITICS: THEORY AND DYNAMICS 2nd Semester Course No. Title PSC-201 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THEORY: Issues and Debates PSC-202 THEORY OF COMPARATIVE POLITICS PSC-203 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT -II PSC-204 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL ISSUES IN INDIA PSC-205 FOREIGN POLICY OF MAJOR POWERS 3rd Semester Course No. Title PSC-301 THEORY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PSC-302 THEORY OF POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY PSC-303 INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-304 HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA PSC-305 INDIA IN WORLD AFFAIRS 4th Semester Course No. Title PSC-401 CHANGING DIMENSIONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION IN INDIA PSC-402 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZIATION AND ADMINISTRIATION PSC-403 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY PSC-404 COMPUTER BASICS: THEORY AND PRACTICE Elective CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-405 (i) 405 (ii) LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN INDIA 405 (iii) ETHICS AND POLITICS 405 (iv) COMPARATIVE FEDERALISM 405 (v) SOCIAL EXCLUSION IN INDIA Courses of Studies for M.A. in Political Science (Under Semester System of Teaching & Examination Effective from the Academic Session 2016-17) SEMESTER-I Course No. PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY Unit-I (i) Political Theory- Evolution, The Traditional Approach; Nature and Scope of Traditional Political Theory; Prime Concerns. (ii) Modern Political Theory- Genesis and Evolution; The Modern Behavioural Approach; Nature and Scope of Modern Political Theory; Prime Concerns. Unit-II (i) Political Decision-making Theory of Harold. D. Laswell – The Concept of Politics as the Societal Decision-making Process; Classification of Societal Values; Role of Elites in the Societal Decision-making Process; Effectiveness and Legitimacy of the Societal Decision-making Structure. -

SS 12 Paper V Half 1 Topic 1B

Systems Analysis of David Easton 1 Development of the General Systems Theory (GST) • In early 20 th century the Systems Theory was first applied in Biology by Ludwig Von Bertallanfy. • Then in 1920s Anthropologists Bronislaw Malinowski ( Argonauts of the Western Pacific ) and Radcliffe Brown ( Andaman Islanders ) used this as a theoretical tool for analyzing the behavioural patterns of the primitive tribes. For them it was more important to find out what part a pattern of behaviour in a given social system played in maintaining the system as a whole, rather than how the system had originated. • Logical Positivists like Moritz Schilick, Rudolf Carnap, Otto Von Newrath, Victor Kraft and Herbert Feigl, who used to consider empirically observable and verifiable knowledge as the only valid knowledge had influenced the writings of Herbert Simon and other contemporary political thinkers. • Linguistic Philosophers like TD Weldon ( Vocabulary of Politics ) had rejected all philosophical findings that were beyond sensory verification as meaningless. • Sociologists Robert K Merton and Talcott Parsons for the first time had adopted the Systems Theory in their work. All these developments in the first half of the 20 th century had impacted on the application of the Systems Theory to the study of Political Science. David Easton, Gabriel Almond, G C Powell, Morton Kaplan, Karl Deutsch and other behaviouralists were the pioneers to adopt the Systems Theory for analyzing political phenomena and developing theories in Political Science during late 1950s and 1960s. What is a ‘system’? • Ludwig Von Bertallanfy: A system is “a set of elements standing in inter-action.” • Hall and Fagan: A system is “a set of objects together with relationships between the objects and between their attributes.” • Colin Cherry: The system is “a whole which is compounded of many parts .. -

Gabriel A. Almond Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6489s0w4 No online items Guide to the Gabriel A. Almond Papers compiled by Stanford University Archives staff Stanford University. Libraries.Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford, California January 2011 Copyright © 2015 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Gabriel A. Almond SC0339 1 Papers Overview Call Number: SC0339 Creator: Almond, Gabriel A. (Gabriel Abraham), 1911-2002 Title: Gabriel A. Almond papers Dates: 1939-2002 Physical Description: 29 Linear feet (38 boxes) Summary: The papers include correspondence, minutes, memoranda, reports, conference materials, and other items pertaining to Almond's academic career, 1964-1986; organizations represented include the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Political Science Association, the National Academy of Sciences, and the Social Science Research Council. Later additions to the papers include correspondence, 1964-2001; manuscripts, typescripts and reprints, 1946-1986; and lecture notes and research files. Language(s): The materials are in English. Repository: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, CA 94305-6064 Email: [email protected] Phone: (650) 725-1022 URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Gift of Gabriel Almond, 1986, and the estate of Gabriel Almond, 2002-2003. Information about Access This collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least 48 hours in advance of intended use. Ownership & Copyright All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. -

American Political Science Association

A MERICAN P OLITICAL S CIENCE ASSOCIATION Assessing (In)Security after the Arab Spring John Gledhill, guest editor, April Longley Alley, Brian McQuinn, and Mohammad Ayatollahi Tabaar Misconceptions and Realities of the 2011 Tunisian Election Moez Habadou and Nawel Amrouche Political Science & Politics Katrina Seven Years On PSO CTOBER 2013, V OLUME 46, N UMBER 4 Christine L. Day American Political Science Association Make plans to attend the 2014 APSA Teaching & Learning Conference The 2014 APSA Teaching & Learning Conference theme is “Teaching Inclusively: Inte- grating Multiple Approaches into the Curriculum.” In this unique meeting, APSA strives to promote the greater understanding of cutting- edge approaches, techniques, and methodologies for the political science classroom. Using a working group format, the conference includes plenaries, tracks, and work- shops on topics such as: t Civic Engagement t Integrating Technology in the t Conflict and Conflict Resolution Classroom t Core Curriculum/General t Internationalizing the Curriculum Education t Teaching and Learning at Community t Curricular and Program Assessment Colleges t Distance Learning t Professional Development t Diversity, Inclusiveness, and Equality t Simulations and Role Play t Graduate Education: Teaching and t Teaching Political Theory and Theories Advising Graduate Students t Teaching Research Methods www.apsanet.org/teachingconference 1527 New Hampshire Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036 | 202.483.2512 | www.apsanet.org ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Ps 134: Comparative Politics of the Middle East

PS 134: COMPARATIVE POLITICS OF THE MIDDLE EAST Malik Mufti Spring 2011 Packard 111 (x 72016) Office Hours: Tuesdays & Thursdays (12:00 – 1:00) Purpose This survey course looks at the political development of the Arab states, Turkey, and Iran since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. It analyzes the various factors that shape the political institutions, actors, and ideologies of these states – factors such as history, culture, religion, economics, and foreign intervention – and tries to reach some conclusions about the prospects for future socio-economic and political change, including liberalization, in the Muslim Middle East. As such, the course seeks to provide students with an empirically rich regional case study of some of the central concerns of comparative politics theory in general. Requirements Class will meet from 10:30 to 11:45 on Tuesdays and Thursdays (D+ block) in Eaton 202. There will be one map quiz (worth 5% of the final grade) on 8 February, one mid-term (30%) on 17 March, and a final exam (40%). Students are expected to do all the assigned readings as well as participate in class discussions, which will count for 25% of the final grade. Readings The following books (indicated in bold in the Course Outline) should be bought at the Tufts Bookstore: 1. Larry Diamond et al. (eds.). Islam and Democracy in the Middle East 2. John L. Esposito. Islam: The Straight Path 3. David E. Long et al. (eds.). The Government and Politics of the Middle East and North Africa 4. Roger Owen. State, Power, and Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East The rest of the readings either have URL's provided in this syllabus for downloading, or will be delivered to you directly.