1 a Theoretical Framework for Exploring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed 393 216 Author Title Report No Pub Date Available From

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 216 EA 027 482 AUTHOR Scribner, Jay D., Ed.; Layton, Donald H., Ed. TITLE The Study of Educational Politics. 1994 Commemorative Yearbook of the Politics of Education Association (1969-1994). Education Policy Perspectives Series. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7507-0419-5 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 225p. AVAILABLE FROM Falmer Press, Taylor & Francis, Inc., 1900 Frost Road, Suite 101, Bristol, PA 19007 (paperback: ISBN-0-7507-0419-5; clothbound: ISBN-0-7507-0418-7). PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Principles; Educational Sociology; Elementary Secondary Education; Feminism; Ideology; International Education; *Policy Analysis; *Policy Formation; Political Influences; *Politics of Education; Role of Education; Values ABSTRACT This book surveys major trends in the politics of education over the last 25 years. Chapters synthesize political and policy developments at local, national, and state levels in the United States, as well as in the international arena. The chapters examine the emerging micropolitics of education and policy-analysis, cultural, and feminist studies. The foreword is by Paul E. Peterson and the introduction by Jay D. Scribner and Donald H.Layton. Chapters include:(1) "Values: The 'What?' of the Politics of Education" (Robert T. Stout, Marilyn Tallerico, and Kent Paredes Scribner) ;(2) "The Politics of Education: From Political Science to Interdisciplinary Inquiry" (Kenneth K. Wong);(3) "The Crucible of Democracy: The Local Arena" (Laurence Iannaccone and Frank W.Lutz); (4) "State Policymaking and School Reform: Influences and Influentials" (Tim L. Mazzoni);(5) "Politics of Education at the Federal Level" (Gerald E. Sroufe) ;(6) "The International Arena: The Global Village" (Frances C. -

Nlrcv20201.Pdf

1 2020 Nancy Lipton Rosenblum Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, Emerita Harvard University Department of Government 1731 Cambridge St. Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Educational Background B.A., Radcliffe College, Social Studies, 1969 Ph.D., Harvard University Political Science, 1973 Teaching Positions Chair, Department of Government, Harvard University, 2004-2010 Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, 2001 to 2016 Faculty Fellow, Safra Center for Ethics, Harvard University, 2003-4 Henry Merritt Wriston Professorship, Brown University, 1997- 2001 Chairperson, Political Science Department, Brown University, 1989-95 Professor, Brown University, 1980-2000 Liberal Arts Fellow, Harvard Law School, 1992-93 Fellow, Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, 1988-89 Visiting Professor, Harvard University, Department of Government, Fall, 1985 Associate Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1977-80 Henry LaBarre Jayne Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1973-77 Publications Books A Lot of People are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy”, with Russell Muirhead (Princeton University Press, 2019) 2 Good Neighbors: The Democracy of Everyday Life in America (Princeton University Press, 2016) On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship (Princeton University Press, 2008) Membership and Morals: The Personal Uses of Pluralism in America (Princeton University -

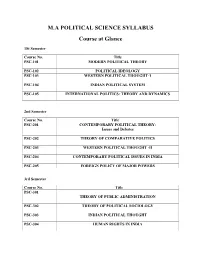

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance 1St Semester Course No. Title PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY PSC-102 POLITICAL IDEOLOGY PSC-103 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT-1 PSC-104 INDIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM PSC-105 INTERNATIONAL POLITICS: THEORY AND DYNAMICS 2nd Semester Course No. Title PSC-201 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THEORY: Issues and Debates PSC-202 THEORY OF COMPARATIVE POLITICS PSC-203 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT -II PSC-204 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL ISSUES IN INDIA PSC-205 FOREIGN POLICY OF MAJOR POWERS 3rd Semester Course No. Title PSC-301 THEORY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PSC-302 THEORY OF POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY PSC-303 INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-304 HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA PSC-305 INDIA IN WORLD AFFAIRS 4th Semester Course No. Title PSC-401 CHANGING DIMENSIONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION IN INDIA PSC-402 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZIATION AND ADMINISTRIATION PSC-403 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY PSC-404 COMPUTER BASICS: THEORY AND PRACTICE Elective CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-405 (i) 405 (ii) LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN INDIA 405 (iii) ETHICS AND POLITICS 405 (iv) COMPARATIVE FEDERALISM 405 (v) SOCIAL EXCLUSION IN INDIA Courses of Studies for M.A. in Political Science (Under Semester System of Teaching & Examination Effective from the Academic Session 2016-17) SEMESTER-I Course No. PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY Unit-I (i) Political Theory- Evolution, The Traditional Approach; Nature and Scope of Traditional Political Theory; Prime Concerns. (ii) Modern Political Theory- Genesis and Evolution; The Modern Behavioural Approach; Nature and Scope of Modern Political Theory; Prime Concerns. Unit-II (i) Political Decision-making Theory of Harold. D. Laswell – The Concept of Politics as the Societal Decision-making Process; Classification of Societal Values; Role of Elites in the Societal Decision-making Process; Effectiveness and Legitimacy of the Societal Decision-making Structure. -

Political Education in the Elementary School: a Decision-Making Rationale

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-6748 COG AN, John Joseph, 1942- POLITICAL EDUCATION IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: A DECISION-MAKING RATIONALE. The Ohio State U niversity, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (£) Copyright by John Joseph Cogan ,1970 POLITICAL EDUCATION IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: A DECISION-MAKING RATIONALE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Joseph Cogan, B.S., M.A, ****** The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by College of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This writer would like to extend hiB appreciation to all who provided guidance and help in any manner during the completion of this study. The writer is indebted immeasurably to his adviser, Professor Raymond H. Muessig, whose patient and continuous counsel made the completion of this study possible. Appreciation is also extended to Professors Robert E. Jewett and Alexander Frazier who served as readers of the dissertation. Finally, the writer is especially grateful to his wife, Norma, and hiB daughter, Susan, whose patience and understanding have been unfailing throughout the course of this study. ii VITA May 30, 19^2 . Born - Youngstown, Ohio 1 9 6 3. B.S., Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 1963-1965.... Elementary Teacher, Columbus Public Schools, Columbus, Ohio I965 ............ M.A., The Ohio State University, ColumbuB, Ohio 1965-1966 .... Graduate Assistant, College of Education, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1966-1967 .... United States Office of Education Fellow, Washington, D.C. Summer, 1967 . Acting Director, Consortium of Professional Associations for the Study of Special Teacher Improvement Programs (CONPASS), Washington, D.C. -

SS 12 Paper V Half 1 Topic 1B

Systems Analysis of David Easton 1 Development of the General Systems Theory (GST) • In early 20 th century the Systems Theory was first applied in Biology by Ludwig Von Bertallanfy. • Then in 1920s Anthropologists Bronislaw Malinowski ( Argonauts of the Western Pacific ) and Radcliffe Brown ( Andaman Islanders ) used this as a theoretical tool for analyzing the behavioural patterns of the primitive tribes. For them it was more important to find out what part a pattern of behaviour in a given social system played in maintaining the system as a whole, rather than how the system had originated. • Logical Positivists like Moritz Schilick, Rudolf Carnap, Otto Von Newrath, Victor Kraft and Herbert Feigl, who used to consider empirically observable and verifiable knowledge as the only valid knowledge had influenced the writings of Herbert Simon and other contemporary political thinkers. • Linguistic Philosophers like TD Weldon ( Vocabulary of Politics ) had rejected all philosophical findings that were beyond sensory verification as meaningless. • Sociologists Robert K Merton and Talcott Parsons for the first time had adopted the Systems Theory in their work. All these developments in the first half of the 20 th century had impacted on the application of the Systems Theory to the study of Political Science. David Easton, Gabriel Almond, G C Powell, Morton Kaplan, Karl Deutsch and other behaviouralists were the pioneers to adopt the Systems Theory for analyzing political phenomena and developing theories in Political Science during late 1950s and 1960s. What is a ‘system’? • Ludwig Von Bertallanfy: A system is “a set of elements standing in inter-action.” • Hall and Fagan: A system is “a set of objects together with relationships between the objects and between their attributes.” • Colin Cherry: The system is “a whole which is compounded of many parts .. -

American Political Science Association

A MERICAN P OLITICAL S CIENCE ASSOCIATION Assessing (In)Security after the Arab Spring John Gledhill, guest editor, April Longley Alley, Brian McQuinn, and Mohammad Ayatollahi Tabaar Misconceptions and Realities of the 2011 Tunisian Election Moez Habadou and Nawel Amrouche Political Science & Politics Katrina Seven Years On PSO CTOBER 2013, V OLUME 46, N UMBER 4 Christine L. Day American Political Science Association Make plans to attend the 2014 APSA Teaching & Learning Conference The 2014 APSA Teaching & Learning Conference theme is “Teaching Inclusively: Inte- grating Multiple Approaches into the Curriculum.” In this unique meeting, APSA strives to promote the greater understanding of cutting- edge approaches, techniques, and methodologies for the political science classroom. Using a working group format, the conference includes plenaries, tracks, and work- shops on topics such as: t Civic Engagement t Integrating Technology in the t Conflict and Conflict Resolution Classroom t Core Curriculum/General t Internationalizing the Curriculum Education t Teaching and Learning at Community t Curricular and Program Assessment Colleges t Distance Learning t Professional Development t Diversity, Inclusiveness, and Equality t Simulations and Role Play t Graduate Education: Teaching and t Teaching Political Theory and Theories Advising Graduate Students t Teaching Research Methods www.apsanet.org/teachingconference 1527 New Hampshire Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036 | 202.483.2512 | www.apsanet.org ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Political Science & Politics

Political Science & Politics Volume XXI Number 2 Spring 1988 "/ <£lVE. TbU A MAM WHO 6 RELI&10U5, QUX Cb NO fAhKTlc; A MAM VVHO ^V&RS ^ ro A eo/Mr; /\ MAN WHO LIKES Private Lives and Public Careers Bruce Buchanan, Ronald Elving and Sanford Levinson 1988 Annual Meeting Preview Chatham House Checklist Box One, Chatham, NJ 07928 Telephone: (201) 635-2059 * Arian: Politics in Israel it Ball: Modern Politics and Government 4ed * Cannon and O'Brien: Views from the Bench * Dalton: Citizen Politics in Western Democracies * Dogan and Pelassy: How to Compare Nations * Dolbeare: American Political Thought * Dolbeare: Democracy at Risk rev ed * Dragnich et al.: Politics and Government 2ed •sir Fry: Masters of Public Administration it Godwin: Direct Marketing of Politics * Goodsell: The Case for Bureaucracy 2ed •sir Hancock: West Germany •sir Hancock et al.: Politics in Western Europe ~k Hershey: Running for Office it Hinckley: The Symbolic Presidency * Hood: Tools of Government * Jacobs et al.: Comparative Politics * Jones: The Reagan Legacy * Kaufman: Time, Chance, and Organizations * King: The State in Modern Society it Lynn &. Wildavsky: Public Administration * McFarland: Common Cause * Meehan: The Thinking Game: A Guide to Effective Study * Orren and Polsby: Media and Momentum: New Hampshire * Peters: American Public Policy 2ed •sir Rose: The Post-Modern Presidency * Sartori: The Theory of Democracy Revisited * Savas: Privatization: The Key to Better Government * Wilson: Business and Politics * Published it Forthcoming On your request for exam copies, please state course title, present text, and enrollment on your letterhead and send it to Edward Artinian, publisher, Chatham House Publishers, Inc., Box One, Chatham, New Jersey 07928 or telephone (201) 635-2059. -

Foundation of Political Science

School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION I SEMESTER B.A POLITICAL SCIENCE (2013 ADMISSION) CORE COURSE FOUNDATION OF POLITICAL SCIENCE QUESTION BANK 1. Who defined political science is “that part of social science which treats the foundations of the foundations of the state and principles of government”? a. Paul Janet; b. Dyke; c. Gettell; d. None of it 2. Who is the author of “A History of Political Theory”? a. Karl Popper; b. Sabine; c. Mill; d. Locke 3. Who described historical approach as ‘historicism’? a. Bentham; b. Hegel; c. Popper; d. Marx 4. Which approach is, according to Rober A Dahl, an attempt to make the empirical content of Political Science more scientific “ a. Institutional Approach c. Philosophical Approach b. Historical Approach d. Behavioural Approach 5. Who introduced ‘intellectual foundations’ for behavioural approach? a. Easton; b. Merriam; c. Lasswell; d. Bentley 6. Who said “the concept of power is the most fundamental in the whole of Political Science: the Political Process is the shaping, dissolution and exercise of power” ? a. Merriam and Easton c. Catlin and Bentley b. Lasswell and Kaplan d. None of them 7. Who is known as the greatest advocate of Post-Behaviouralism? a. Merriam; b. Easton; c. Lasswell; d. Bentley 8. Which approach demands ‘relevance’ and ‘action’? a. Institutional Approach c. Behaviouralist b. Post-Behaviouralist Approach d. Historical Approach 9. Whose definition encompasses the ‘politics of consent’ as well as the ‘politics of struggle’? a. Easton; b. Merriam; c. Lasswell; d. Kaplan 10. Who introduced ‘politics of consent’ ? a. Lasswell; b. -

Scott L. Althaus

Althaus – 1 SCOTT L. ALTHAUS Cline Center for Advanced Social Research Office: 217.265.7845 University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign Fax: 217.265.7880 2001 South First St., Suite 207 E‐mail: [email protected] Champaign, IL 61820‐7461 Web: www.illinois.edu/~salthaus CURRENT APPOINTMENTS Merriam Professor of Political Science and Professor of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign (2012‐present). Director of the Cline Center for Advanced Social Research, University of Illinois at Urbana‐ Champaign (2014‐present) Faculty Affiliate of the following University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign units: School of Information Sciences (2016‐present) National Center for Supercomputer Applications (2014‐present) Institute for Computing in the Humanities and Social Sciences (2014‐present) Illinois Informatics Institute (2011‐present) PAST APPOINTMENTS Associate Director of the Cline Center for Democracy, University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign (2011‐2014) Associate Professor, Department of Political Science and Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign (2003‐2012). Assistant Professor, Department of Communication and Department of Political Science, University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign (1996‐2003). EDUCATION NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Ph.D. in Political Science with certificate in Political Communication, December 1996. M.A. in Political Science, June 1993. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY B.A. in Rhetoric with honors, May 1991. Departmental honors, Phi Beta Kappa. DIABLO VALLEY COLLEGE, PLEASANT HILL, CA General education studies, 1987‐89. BOOKS Althaus, Scott. In preparation. Time in the Fight: Understanding Popular Support for America’s Wars. Under contract with Cambridge University Press. Althaus, Scott. 2003. Collective Preferences in Democratic Politics: Opinion Surveys and the Will of the People. -

TRANSFORMATIONS B Comparative Study of Social Transformations

TRANSFORMATIONS B comparative study of social transformations CSST WORKING PAPERS The University of Michigan Ann Arbor "The Return of the State"" Timothy Mitchell CSST Working CRSO Working Paper #?4 Paper 9410 May 1992 THE RETURN OF THE STATE Timothy Mitchell Department of Politics New York University Draft. Please do not quote without permission An earlier and shorter version of this paper was published as "The Limits of the State," American Political Science Review (1991). The state is an object of analysis that appears to exist simultaneously as material force and ideological construct, as something both real and illusory. This seemingly obvious yet paradoxical fact is the source of considerable theoretical difficulty. Not the least of these difficulties is that the network of institutional arrangement and political practice that forms the material substance of the state tends to be diffuse and ambiguously defined at its edges, whereas the public imagery of the state as an ideological construct tends towards coherence, unity and function. The scholarly analysis of the state is liable to reproduce in its own analytical tidiness this imaginary coherence, and misrepresent the incoherence of material practice. Drawing attention to this liability, Philip Abrams (1988) argues that we should distinguish sharply between two objects of analysis, the wstate-system" and the "state-idea." The first refers to the state as a system of institutionalized practice, the second to the reification of this system that takes on "an overt symbolic identity progressively divorced from practice as an illusory account of practice.I1. We should avoid mistaking the latter for the former, he suggests, by "attending to the senses in which the state does not exist rather than those in which it doesw (p. -

American Political Science Association

PROGRAM 81st Annual Meeting American Political Science Association August 29-September 1, 1985 New Orleans, LA From the center of political activity: Prentice-Hall's 1986 IPOLITICAL SCIENCE HTLESI AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY: AN INTRODUCTION TO PUBLIC A Contemporary Introduction,Second Edition POLICY Brewer 8/85 Koenig 2/86 AMERICAN GOVERNMENT, THE PHILOSOPHIC ROOTS OF Fourth Edition MODERN IDEOLOGY: Volkomer 10/85 Liberalism, Communism, Fascism AMERICAN INTERGOVERNMENTAL Ingersoll/Matthews 7/85 RELATIONS TODAY: PRINCIPLES OF AMERICAN Perspectives and Controversies GOVERNMENT, Tenth Edition Dilger 10/85 Saye/Allums 11/85 APPROACHING PUBLIC POLICY PRINCIPLES OF POLITICS: ANALYSIS: An Introduction to Policy An Introduction and Program Research Schrems 9/85 Portney 1/86 PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND BASIC METHODS OF POLICY PUBLIC AFFAIRS, Third Edition ANALYSIS AND PLANNING Henry 1/86 Patton/Sawicki 11/85 THE REAL AMERICAN POLITICS ' CIVIL LIBERTIES AND THE Hummel/Isaak 1/86 CONSTITUTION: THE RESURGENCE OF THE STATES Cases and Commentaries, Fifth Edition Bowman/Kearney 1/86 «- Barker/Barker 12/85 SOVIET POLITICAL SOCIETY CLASSICS OF INTERNATIONAL Baradat 1/86 RELATIONS STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT: * Vasquez 10/85 The New Battleground COMPARATIVE POLITICS: Housemen 11/85 An Introduction to Six Countries STATE AND LOCAL POLITICS: <! Theen/Wilson 1/86 The Great Entanglement CONGRESS AND THE PRESIDENCY, Lorch 11/85 Fourth Edition URBAN POLICY AND POLITICS J Polsby 11/85 IN A BUREAUCRATIC AGE, COUNTRIES AND CONCEPTS: Second Edition An Introduction to Comparative Politics, Stone/Whelan/Murin 9/85 * Second Edition WHO'S RUNNING AMERICA? Roskin 11/85 The Conservative Years, Fourth Edition DEMOCRACY IN THE MAKING, Dye 10/85 , Second Edition WOMEN LEADERS IN AMERICAN Burnham 2/86 POLITICS HOW CHINA IS RULED Barber/Kellerman 10/85 s Liu 7/85 INTRODUCTION TO INTERNATIONAL To request your examination copy(ies), please RELATIONS: Power and Justice, write to: Robert Jordan, Dept. -

American Political Science Review

TRIM SIZE 209.5X279.4MM AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW AMERICAN https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000369 . POLITICAL https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms SCIENCE REVIEW , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available 25 Sep 2021 at 01:24:13 , on August 2018, Volume 112, Issue 3 112, Volume 2018, August 170.106.33.14 . IP address: August 2018 Volume 112, Issue 3 Cambridge Core For further information about this journal https://www.cambridge.org/core ISSN: 0003-0554 please go to the journal website at: cambridge.org/apsr Downloaded from 00030554_112-3.indd 1 29/06/18 3:15 PM TRIM SIZE 209.5X279.4MM LEAD EDITOR Jennifer Gandhi Andreas Schedler Thomas König Emory University Centro de Investigación y Docencia University of Mannheim, Germany Claudine Gay Económicas, Mexico Harvard University Frank Schimmelfennig ASSOCIATE EDITORS John Gerring ETH Zürich, Switzerland Kenneth Benoit University of Texas, Austin Carsten Q. Schneider London School of Economics Sona N. Golder Central European University, and Political Science Pennsylvania State University Budapest, Hungary Thomas Bräuninger Ruth W. Grant Sanjay Seth University of Mannheim Duke University Goldsmiths, University of London, UK Sabine Carey Julia Gray Carl K. Y. Shaw University of Mannheim University of Pennsylvania Academia Sinica, Taiwan Leigh Jenco Mary Alice Haddad Betsy Sinclair London School of Economics Wesleyan University Washington University in St. Louis and Political Science Peter A. Hall Beth A. Simmons Benjamin Lauderdale Harvard University University of Pennsylvania London School of Economics Mary Hawkesworth Dan Slater and Political Science Rutgers University University of Chicago Ingo Rohlfi ng Gretchen Helmke Rune Slothuus University of Cologne https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000369 University of Rochester Aarhus University, Denmark .