Livingston Code, the Elon H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Selected Papers of John Jay, 1760-1779 Volume 1 Index

The Selected Papers of John Jay, 1760-1779 Volume 1 Index References to earlier volumes are indicated by the volume number followed by a colon and page number (for example, 1:753). Achilles: references to, 323 Active (ship): case of, 297 Act of 18 April 1780: impact of, 70, 70n5 Act of 18 March 1780: defense of, by John Adams, 420; failure of, 494–95; impact of, 70, 70n5, 254, 256, 273n10, 293, 298n2, 328, 420; passage of, 59, 60n2, 96, 178, 179n1 Adams, John, 16, 223; attitude toward France, 255; and bills of exchange, 204n1, 273– 74n10, 369, 488n3, 666; and British peace overtures, 133, 778; charges against Gillon, 749; codes and ciphers used by, 7, 9, 11–12; and commercial regulations, 393; and commercial treaties, 645, 778; commissions to, 291n7, 466–67, 467–69, 502, 538, 641, 643, 645; consultation with, 681; correspondence of, 133, 176, 204, 393, 396, 458, 502, 660, 667, 668, 786n11; criticism of, 315, 612, 724; defends act of 18 March 1780, 420; documents sent to, 609, 610n2; and Dutch loans, 198, 291n7, 311, 382, 397, 425, 439, 677, 728n6; and enlargement of peace commission, 545n2; expenses of, 667, 687; French opposition to, 427n6; health of, 545; identified, 801; instructions to, 152, 469–71, 470–71n2, 502, 538, 641, 643, 657; letters from, 115–16, 117–18, 410–11, 640–41, 643–44, 695–96; letters to, 87–89, 141–43, 209–10, 397, 640, 657, 705–6; and marine prisoners, 536; and mediation proposals, 545, 545n2; as minister to England, 11; as minister to United Provinces, 169, 425; mission to Holland, 222, 290, 291n7, 300, 383, 439, -

The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York Melinda M. Mohler West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Mohler, Melinda M., "A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4755. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4755 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York Melinda M. Mohler Dissertation submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Jack Hammersmith, Ph.D., Chair Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D. Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. Kenneth Fones-World, Ph.D. Martha Pallante, Ph.D. -

H. Doc. 108-222

EIGHTEENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1823, TO MARCH 3, 1825 FIRST SESSION—December 1, 1823, to May 27, 1824 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1824, to March 3, 1825 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—DANIEL D. TOMPKINS, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOHN GAILLARD, 1 of South Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—CHARLES CUTTS, of New Hampshire SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MOUNTJOY BAYLY, of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—HENRY CLAY, 2 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—MATTHEW ST. CLAIR CLARKE, 3 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DUNN, of Maryland; JOHN O. DUNN, 4 of District of Columbia DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN BIRCH, of Maryland ALABAMA GEORGIA Waller Taylor, Vincennes SENATORS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES William R. King, Cahaba John Elliott, Sunbury Jonathan Jennings, Charlestown William Kelly, Huntsville Nicholas Ware, 8 Richmond John Test, Brookville REPRESENTATIVES Thomas W. Cobb, 9 Greensboro William Prince, 14 Princeton John McKee, Tuscaloosa REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Gabriel Moore, Huntsville Jacob Call, 15 Princeton George W. Owen, Claiborne Joel Abbot, Washington George Cary, Appling CONNECTICUT Thomas W. Cobb, 10 Greensboro KENTUCKY 11 SENATORS Richard H. Wilde, Augusta SENATORS James Lanman, Norwich Alfred Cuthbert, Eatonton Elijah Boardman, 5 Litchfield John Forsyth, Augusta Richard M. Johnson, Great Crossings Henry W. Edwards, 6 New Haven Edward F. Tattnall, Savannah Isham Talbot, Frankfort REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Wiley Thompson, Elberton REPRESENTATIVES Noyes Barber, Groton Samuel A. Foote, Cheshire ILLINOIS Richard A. Buckner, Greensburg Ansel Sterling, Sharon SENATORS Henry Clay, Lexington Ebenezer Stoddard, Woodstock Jesse B. Thomas, Edwardsville Robert P. Henry, Hopkinsville Gideon Tomlinson, Fairfield Ninian Edwards, 12 Edwardsville Francis Johnson, Bowling Green Lemuel Whitman, Farmington John McLean, 13 Shawneetown John T. -

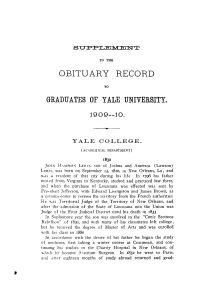

Obituary Record

S U TO THE OBITUARY RECORD TO GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVEESITY. 1909—10. YALE COLLEGE. (ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT) 1832 JOHN H \MPDFN LEWIS, son of Joshua and America (Lawson) Lewis, was born on September 14, 1810, m New Orleans, La, and was a resident of that city during his life In 1796 his father moved from Virginia to Kentucky, studied and practiced law there, and when the purchase of Louisiana was effected was sent by President Jefferson, with Edward Livingston and James Brown, as a commisMoner to receive the territory from the French authorities He was Territorial Judge of the Territory of New Orleans, and after the admission of the State of Louisiana into the Union was Judge of the First Judicial District until his death in 1833 In Sophomore year the son was involved in the "Conic Sections Rebellion" of 1830, and with many of his classmates left college, but he received the degree of Master of Arts and was enrolled with his class in 1880 In accordance with the desire of his father he began the study of medicine, first taking a winter course at Cincinnati, and con- tinuing his studies in the Charity Hospital in New Orleans, of which he became Assistant Surgeon In 1832 he went to Pans, and after eighteen months of study abroad returned and grad- YALE COLLEGE 1339 uated in 1836 with the first class from the Louisiana Medical College After having charge of a private infirmary for a time he again went abroad for further study In order to obtain the nec- essary diploma in arts and sciences he first studied in the Sorbonne after which he entered -

John Trumbull of the Signing of the Declaration of Independence

Bicentennial Moment #2: the Naming of Livingston County, New York Livingston County was named in honor of Chancellor Robert R. Livingston (1746-1813), a man who never resided Livingston County, but who was among the Founding Fathers of the United States of America. Livingston was the eldest son of Judge Robert Livingston (1718–1775) and Margaret (née Beekman) Livingston, uniting two wealthy Hudson River Valley families. Among his many contributions, Livingston was a member of the Second Continental Congress, co-author of the Declaration of Independence, and in 1789 he administered the oath of office to President George Washington. As a member of the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence, Livingston worked alongside Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Roger Sherman. A regional and national luminary, Livingston served as Chancellor of the Supreme Court of New York (1777 to 1801). As the United States Minister to France from 1801 to 1804, he was one of the key figures in negotiating the Louisiana Purchase with Napoleon Bonaparte, a sale that marked a turning point in the relationship between the two nations. During his time as U.S. Minister to France, Livingston met Robert Fulton, with whom he developed the first viable steamboat, the North River Steamboat, whose home port was at the Livingston family home of Clermont Manor in Clermont, New York. In addition to the naming of Livingston County in his honor, Robert R. Livingston's legacy lives on in numerous ways including a statue commissioned by the State of New York and placed in the National Statuary Hall at the U.S. -

2019-2020 Missouri Roster

The Missouri Roster 2019–2020 Secretary of State John R. Ashcroft State Capitol Room 208 Jefferson City, MO 65101 www.sos.mo.gov John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State Cover image: A sunrise appears on the horizon over the Missouri River in Jefferson City. Photo courtesy of Tyler Beck Photography www.tylerbeck.photography The Missouri Roster 2019–2020 A directory of state, district, county and federal officials John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State Office of the Secretary of State State of Missouri Jefferson City 65101 STATE CAPITOL John R. Ashcroft ROOM 208 SECRETARY OF STATE (573) 751-2379 Dear Fellow Missourians, As your secretary of state, it is my honor to provide this year’s Mis- souri Roster as a way for you to access Missouri’s elected officials at the county, state and federal levels. This publication provides contact information for officials through- out the state and includes information about personnel within exec- utive branch departments, the General Assembly and the judiciary. Additionally, you will find the most recent municipal classifications and results of the 2018 general election. The strength of our great state depends on open communication and honest, civil debate; we have been given an incredible oppor- tunity to model this for the next generation. I encourage you to par- ticipate in your government, contact your elected representatives and make your voice heard. Sincerely, John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State www.sos.mo.gov The content of the Missouri Roster is public information, and may be used accordingly; however, the arrangement, graphics and maps are copyrighted material. -

Sarah Livingston Jay, 1756--1802: Dynamics of Power, Privilege and Prestige in the Revolutionary Era

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2005 Sarah Livingston Jay, 1756--1802: Dynamics of power, privilege and prestige in the Revolutionary era Jennifer Megan Janson West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Janson, Jennifer Megan, "Sarah Livingston Jay, 1756--1802: Dynamics of power, privilege and prestige in the Revolutionary era" (2005). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 797. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/797 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sarah Livingston Jay, 1756-1802: Dynamics of Power, Privilege and Prestige in the Revolutionary Era Jennifer Megan Janson Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Colonial and Revolutionary History Robert Blobaum, Ph.D., Department Chair Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D., Committee Chair Ken Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. -

RG 68 Master Calendar

RG 68 MASTER CALENDAR Louisiana State Museum Historical Center Archives May 2012 Date Description 1387, 1517, 1525 Legal document in French, Xerox copy (1966.011.1-.3) 1584, October 20 Letter, from Henry IV, King of France, to Francois de Roaldes (07454) 1640, August 12 1682 copy of a 1640 Marriage contract between Louis Le Brect and Antoinette Lefebre (2010.019.00001.1-.2) 1648, January 23 Act of sale between Mayre Grignonneau Piqueret and Charles le Boeteux (2010.019.00002.1-.2) 1680, February 21 Photostat, Baptismal certificate of Jean Baptoste, son of Charles le Moyne and marriage contract of Charles le Moyne and Catherine Primot (2010.019.00003 a-b) 1694 Reprint (engraving), frontspiece, an Almanack by John Tulley (2010.019.00004) c. 1700-1705 Diary of Louisiana in French (2010.019.00005 a-b) c. 1700 Letter in French from Philadelphia, bad condition (2010.019.00006) 1711, October 18 Document, Spanish, bound, typescript, hand-illustrated manuscript of the bestowing of a title of nobility by Charles II of Spain, motto on Coat of Arms of King of Spain, Philippe V, Corella (09390.1) 1711, October 18 Typescript copy of royal ordinance, bestows the title of Marquis deVillaherman deAlfrado on Dr. Don Geronina deSoria Velazquez, his heirs and successors as decreed by King Phillip 5th, Spain (19390.2) 1714, January 15 English translation of a letter written at Pensacola by M. Le Maitre, a missionary in the country (2010.019.00007.1-.29) 1714 Document, translated into Spanish from French, regarding the genealogy of the John Douglas de Schott family (2010.019.00008 a-b) 1719, December 29 Document, handwritten copy, Concession of St. -

The Colonial Family: Kinship Nd Power Peter R

The Colonial Family: Kinship nd Power Peter R. Christop New York State Library ruce C. Daniels in a 1985 book review wrote: “Each There is a good deal of evidence in the literature, year since the late 1960sone or two New England town therefore, that in fact the New England town model may studies by professional historians have been published; not at all be the ideal form to use in studying colonial lheir collective impact has exponentially increased our New York social structure. The real basis of society was knowledge of the day-to-day life of early America.“’ not the community at all, but the family. The late Alice One wonders why, if this is so useful an historical P. Kenney made the first step in the right direction with approach, we do not have similar town studies for New her study of the Gansevoort family.6 It is indeed the York. It is not for lack of recordsthat no attempt hasbeen family in colonial New York that historians should be made. Nor can one credit the idea that modern profes- studying, yet few historians have followed Kenney’s sional historians, armed with computers, should feel in lead. A recent exception of note is Clare Brandt’s study any way incapable of dealing with the complexity of a of the Livingston family through several generations.7 multinational, multiracial, multireligious community. However, we should note that Kenney and Brandt have restricted their attention to persons with one particular One very considerable problem for studying the surname, ignoring cousins, grandparents, and colonial period was the mobilily Qf New Yorkers, grandchildren with other family namesbut nonetheless especially the landed and merchant class. -

Craft Horizons JULY/AUGUST 1968 a SHOPPING CENTER Ahme for JEWELRY CRAFTSMEN at Your Fingertips! KILNS & CERAMIC EQUIPMENT GAS KILNS from 2 Cu

craft horizons JULY/AUGUST 1968 A SHOPPING CENTER Ahme FOR JEWELRY CRAFTSMEN at your fingertips! KILNS & CERAMIC EQUIPMENT GAS KILNS from 2 cu. ft. to 60 cu. ft. All fire to 2500°F — some to 3000°F. Instrumentation for temperature control and a positive control of atmosphere from highly oxidizing to reducing. ELECTRIC KILNS from 2 cu. ft. to 24 cu. ft. Front loading or top loading — all models fire to 2350°F — some to 2800' F. Fully instrumented. complete catalog of... TOOLS AND SUPPLIES We've spent one year working, compiling and publishing our new 244-page Catalog 1065 ... now it is available. We're mighty proud of this new one. .. because we've incor- porated brand new never-before sections on casting equipment, electroplating equipment and precious metals... We spent literally months redesigning the metals section . giving it clarity ... yet making it concise and with lots of information ... Your 244-page catalog is waiting for you ... just send us $1.00 ... and we'll send you the largest and most complete catalog A wide selection of in the industry. With it you'll receive a certificate ... and POTTERY WHEEL when you send it in with your first order of $5.00 or more... models are available we'll deduct the $1.00 from the order. Order your catalog today . we're certain you'll find it the best "wish-book" you ever had . besides it is destined to become THE encyclopedia of tools and supplies for crafts and jewelry people. Ij| CH WRITE TODAY for COMPLETE information Dept. -

1 Record Group 1 Judicial Records of the French

RECORD GROUP 1 JUDICIAL RECORDS OF THE FRENCH SUPERIOR COUNCIL Acc. #'s 1848, 1867 1714-1769, n.d. 108 ln. ft (216 boxes); 8 oversize boxes These criminal and civil records, which comprise the heart of the museum’s manuscript collection, are an invaluable source for researching Louisiana’s colonial history. They record the social, political and economic lives of rich and poor, female and male, slave and free, African, Native, European and American colonials. Although the majority of the cases deal with attempts by creditors to recover unpaid debts, the colonial collection includes many successions. These documents often contain a wealth of biographical information concerning Louisiana’s colonial inhabitants. Estate inventories, records of commercial transactions, correspondence and copies of wills, marriage contracts and baptismal, marriage and burial records may be included in a succession document. The colonial document collection includes petitions by slaves requesting manumission, applications by merchants for licenses to conduct business, requests by ship captains for absolution from responsibility for cargo lost at sea, and requests by traders for permission to conduct business in Europe, the West Indies and British colonies in North America **************************************************************************** RECORD GROUP 2 SPANISH JUDICIAL RECORDS Acc. # 1849.1; 1867; 7243 Acc. # 1849.2 = playing cards, 17790402202 Acc. # 1849.3 = 1799060301 1769-1803 190.5 ln. ft (381 boxes); 2 oversize boxes Like the judicial records from the French period, but with more details given, the Spanish records show the life of all of the colony. In addition, during the Spanish period many slaves of Indian 1 ancestry petitioned government authorities for their freedom. -

Columbia County

History of Columbia County Bench and Bar Helen E. Freedman Contents I. County Origins 2 a. General Narrative 2 b. Legal and Social Beginnings 3 c. Timeline 4 II. County Courts and Courthouses 6 III. The Bench and The Bar 10 a. Judges and Justices 10 b. Attorneys and District Attorneys 19 c. Columbia County Bar Association 24 IV. Notable Cases 25 V. County Resources and References 28 a. Bibliography 28 b. County Legal Records and their Location 28 c. County History Contacts 29 i. Town and Village Historians 30 ii. Local Historical Societies 31 iii. County, Town & Village Clerks 32 1 08/13/2019 I. County Origins a. General Narrative In September of 1609, Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company, set foot in what was to become Columbia County. When he stepped off his vessel, the Half Moon, he was the first European to arrive and was greeted by natives from the Mohican tribes who had settled in what is Stockport today.1 Starting in about 1620, Dutch immigrants settled the area along the Hudson River and extending east to the Massachusetts border, pursuant to land patents issued by the Dutch West India Company. Large manorial tracts were granted to the Van Rensselaer family, mostly in the northern part of the county and further north, starting in 1629. Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, a dia- mond and pearl merchant from Amsterdam and a director of the Dutch West India Company, founded the Manor of Rensselaerswyck in 1630, which included what is now the Capital District and Rensselaer and part of Columbia Counties.