Whanake the Pacific Journal of Community Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Demographic Transformation of Inner City Auckland

New Zealand Population Review, 35:55-74. Copyright © 2009 Population Association of New Zealand The Demographic Transformation of Inner City Auckland WARDLOW FRIESEN * Abstract The inner city of Auckland, comprising the inner suburbs and the Central Business District (CBD) has undergone a process of reurbanisation in recent years. Following suburbanisation, redevelopment and motorway construction after World War II, the population of the inner city declined significantly. From the 1970s onwards some inner city suburbs started to become gentrified and while this did not result in much population increase, it did change the characteristics of inner city populations. However, global and local forces converged in the 1990s to trigger a rapid repopulation of the CBD through the development of apartments, resulting in a great increase in population numbers and in new populations of local and international students as well as central city workers and others. he transformation of Central Auckland since the mid-twentieth century has taken a number of forms. The suburbs encircling the TCentral Business District (CBD) have seen overall population decline resulting from suburbanisation, as well as changing demographic and ethnic characteristics resulting from a range of factors, and some areas have been transformed into desirable, even elite, neighbourhoods. Towards the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty first century, a related but distinctive transformation has taken place in the CBD, with the rapid construction of commercial and residential buildings and a residential population growth rate of 1000 percent over a fifteen year period. While there are a number of local government and real estate reports on this phenomenon, there has been relatively little academic attention to its nature * School of Environment, The University of Auckland. -

Te Rimu Tahi, Ponsonby Road Masterplan

Te Rimu Tahi Ponsonby Road Masterplan - Maori Heritage Report June 2013 Ngarimu Blair for Auckland Council 1 1. Introduction The Waitemata Local Board and representatives from a number of community groups (supported by Auckland Council and Auckland Transport) are working together to develop a Master Plan for Ponsonby Road. The Ponsonby Road Master Plan will present a comprehensive blue print for improvement to the urban realm of Ponsonby Road over the next 30 years. The Master Plan will be prepared following a ‘complete street/ living arterial’ approach. The Master Plan is intended to facilitate the achievement of an urban realm that better meets the community's desired outcomes in the future. The Auckland Council commissioned this report on Maori heritage values and opportunities from Ngarimu Blair in order to better engage with relevant Iwi for the project area. The Iwi listed by Auckland Council for this project includes Ngati Te Ata, Te Aakitai, Ngati Whatua Orakei, Te Runanga o Ngati Whatua, Ngai Tai ki Tamaki, Ngati Maru, Ngati Paoa and Te Kawerau a Maki. Specifically the brief for this report is; Background research to identify areas of past (pre-European) Maori Occupation, Use and activity within the Ponsonby Road Master Plan study area; Background research to identify the more recent history of Urban Maori activity within the Ponsonby Road Master Plan study area; and Preparation of a short report outlining the findings of this research, which specifically provides: (1) an historic context statement; (2) a short issues analysis that identifies high-level positive, negative, and neutral issues (with regard to cultural heritage) and gaps in information that could not be filled through research or within the timeframe; and (3) recommendations for preservation, protection or celebration of the cultural heritage. -

Waitematā Local Board Meeting Held on 16/07/2019

Waitematā Local Board Open Space Network Plan 2019 - 2029 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Executive Summary 5 1 Introduction 6 1.1 Purpose of the network plan 6 Network plan implementation 6 1.2 Strategic context 7 1.3 The legislative context 8 Auckland Council’s approach 8 Service Property Optimisation 8 1.4 Waitematā Local Board area 9 Waitematā Local Board’s parks and open spaces 10 Mana whenua iwi 10 Population trends 11 What this means 12 1.5 Current State 12 1.6 Treasure 12 Cultural Heritage 12 Te ao Māori (the Māori world view) 12 Historic places 13 Colonial heritage 13 Natural Heritage 14 Biodiversity 17 A community that cares about its environment 17 1.7 Enjoy 18 Housing developments 18 Parks provision 19 Sportsground provision 20 Waitematā’s youth 20 1.8 Connect 22 Esplanade reserves 22 Walking and cycling networks 22 Waitematā Greenways Plan 22 Linear parks 24 1.9 Utilise 24 Expanding the city centre network 24 Satisfaction with parks 24 Environmental quality 25 Contaminated soil 25 Green infrastructure 26 Network infrastructure 27 Connecting communities 28 Leases 29 2 Key moves 31 2.1 2.1 Four key moves 31 2.2 Key Move 1 - Respond to the growth of our increasingly diverse communities 32 Provision/gap analysis 32 Land optimisation 32 Repurposing and shared use 32 Park management plans 34 Development plans 36 Spatial plans 36 2.3 Key move 2 – activate and enhance our open spaces 37 Recreation 37 Seating 38 Shade 38 Activation 38 Out-and-About programme 38 Community gardens 38 Play 39 2.4 Key move 3 – improve biodiversity -

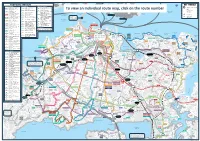

To View an Individual Route Map, Click on the Route Number

Ngataringa Bayswater PROPOSED SERVICES Bay KEY SYMBOLS FREQUENT SERVICES LOCAL SERVICES PEAK PERIOD SERVICES Little Shoal Station or key connection point Birkenhead Bay Northwestern Northwest to Britomart via Crosstown 6a Crosstown 6 extension to 101 Pt Chevalier to Auckland University services Northwestern Motorway and Selwyn Village via Jervois Rd Northcote Cheltenham Rail Line Great North Rd To viewNorthcote an individualPoint route map, click on the route number (Passenger Service) Titirangi to Britomart via 106 Freemans Bay to Britomart Loop 209 Beach North Shore Northern Express routes New North Rd and Blockhouse Bay Stanley Waitemata service Train Station NX1, NX2 and NX3 138 Henderson to New Lynn via Mangere Town Centre to Ferries to Northcote, Point Harbour City LINK - Wynyard Quarter to Avondale Peninsula Wynyard Quarter via Favona, Auckland Harbour Birkenhead, West Harbour, North City Link 309X Bridge Beach Haven and Karangahape Rd via Queen St 187 Lynfield to New Lynn via Mangere Bridge, Queenstown Rd Ferries to West Harbour, Hobsonville Head Ferry Terminal Beach Haven and Stanley Bay (see City Centre map) Blockhouse Bay and Pah Rd (non stop Hobsonville Services in this Inner LINK - Inner loop via Parnell, Greenwoods Corner to Newmarket) Services to 191 New Lynn to Blockhouse Bay via North Shore - direction only Inner Link Newmarket, Karangahape Rd, Avondale Peninsula and Whitney St Panmure to Wynyard Quarter via Ferry to 701 Lunn Ave and Remuera Rd not part of this Ponsonby and Victoria Park 296 Bayswater Devonport Onehunga -

Future Auckland

FUTURE AUCKLAND EDUCATION KIT AUCKLAND MUSEUM AUCKLAND CITY Auckland Museum Te Papa Whakahiku C ontents Contents page Introduction to the Resource 02 Why Study the City's Future? 02 Exhibit Your Work at the Auckland Museum 03 Teacher Background 04 The First People of Auckland 04 The Early Days of Auckland 04 Auckland War Memorial Museum 07 Auckland City Council 09 Population of Auckland City 10 Future Trends and Options 11 Curriculum Links 12 Level 2 Pre and Post-Visit Activities 12 Level 3 Pre and Post-Visit Activities 14 Level 4 Pre and Post-Visit Activities 15 Level 5 Pre and Post-Visit Activities 17 Activity Sheets 20 Museum Trails 39 MUSEUM ACTIVITIES March 30 - May 28 'Future Auckland' an inter- active display of possible futures. Venue: Treasures & Tales Discovery Centre. June 1 - July 31 'Future Auckland - Student Vision' a display of student's work. Venue: Treasures & Tales Discovery Centre. Museum Trail of Auckland’s Past. Venue: Auckland 1866 and Natural History Galleries. HOW DO YOU MAKE A BOOKING? Booking before your visit is essential and ensures you have the centre to yourself (depending on the size of your group), or are sharing it with another group of similar age. Book early. Phone: (09) 306 7040 Auckland Museum 1 Introduction to the Resource Intro It is difficult to consider the future with- Why Study the duction out first contemplating how the past has City's Future? shaped our present, be it attitudes, sys- In order to make decisions affecting our tems or environment. future, it is vital to consider the alterna- tives and choices that are available. -

Engineering Walk Final with out Cover Re-Print.Indd

Heritage Walks _ The Engineering Heritage of Auckland 5 The Auckland City Refuse Destructor 1905 Early Electricity Generation 1908 9 Wynyard Wharf 1922 3 13 Auckland Electric 1 Hobson Wharf The New Zealand National Maritime Museum Tramways Co. Ltd Princes Wharf 1937 1989 1899–1902 1921–24 12 7 2 The Viaduct 10 4 11 The Auckland Gasworks, Tepid Baths Lift Bridge The Auckland Harbour Bridge The Sky Tower Viaduct Harbour first supply to Auckland 1865 1914 1932 1955-59 1997 1998-99 Route A 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Route B 14 Old 15 Auckland High Court 13 The Old Synagogue 1 10 Albert Park 1942 Government 1865-7 1884-85 The Ferry Building House 1912 1856 16 Parnell Railway Bridge and Viaduct 5 The Dingwall Building 1935 1865-66 3 Chief Post Office 1911 The Britomart Transport Centre 7 The Ligar Canal, named 1852, improved 1860s, covered 1870s 6 8 Civic Theatre 1929 2001-2004 New Zealand 9 Guardian Trust The Auckland Town Hall Building 1911 1914 17 The Auckland Railway Station 1927-37 11 Albert Barracks Wall 2 Queens Wharf 1913 1846-7 4 The Dilworth Building 1926 12 University of Auckland Old Arts Building 1923-26 10 Route A, approx 2.5 hours r St 9 Route B, approx 2.5 hours Hame Brigham St Other features Jellicoe St 1 f r ha W Madden s 2 e St St rf Princ a 12 h 13 W s Beaumont START HERE een 11 Qu Pakenha m St St 1 son ob H St bert y St n St Gaunt St Al 2 e e Pakenh S ue ket Place H1 am Q Hals St 3 ar Customs M St Quay St 3 4 18 NORTH Sw 8 St anson S Fanshawe t 5 7 6 Wyn Shortla dham nd -

Eight Transformational Moves - Ideas, Programmes and This Transformation

City Centre Masterplan 2020 Transformational Moves: Full Text September 2019 City Centre Masterplan Refresh We want your feedback on the future planning of Auckland’s Since 2012: What has been done so far city centre. The City Centre Masterplan and The Waterfront Plan are being refreshed and combined as part of a six-yearly • The resident population has increased from 24,000 to over The original City Centre Masterplan and Waterfront Plan upgrade. 55,000 were adopted in 2012. We need to keep them up-to-date and • The number of daily workers has jumped from 90,000 to relevant in line with other high-level planning documents. The City Centre Masterplan refresh is a high-level, non- over 120,000 statutory document that supports the Auckland Plan 2050 and • Every day over 200,000 people visit the city centre The City Centre Masterplan refresh looks to build on the 2012 Auckland Unitary Plan. Together with the Waitematā Local • An estimated 20 per cent of Auckland’s gross domestic plans taking them online and combining them to: Board Plan, these documents provide the overall vision that sets product is now generated from the city centre alone. the direction for Auckland’s city centre. • Showcase progress Auckland continues to grow at an unprecedented rate. Right • Reconfirm strategic direction Have your say on the City Centre Masterplan refresh [h3] now, there is $73 billion of commercial construction across the • Highlight specific new initiatives and projects – most region and more than 150 major development projects either in notably Access for Everyone Your feedback will help shape the vision for Auckland’s city progress or in the pipeline. -

10 Reasons to Choose Neo 1. Walking Distance to the Auckland

Situated on an elevated site in a quiet Grafton cul-de-sac, Neo is an upmarket, city-fringe apartment development in the sought-after Grammar Zone. Located in the centre of Auckland’s most-desirable suburbs, Neo is just a short walk from the CBD and Newmarket, and provides easy motorway access and numerous public transport options, so you can enjoy all this wonderful city has to offer. A RISLAND DEVELOPMENT 5 - 9 Madeira Lane, Grafton, Auckland 0508 009 888 neoapartments.co.nz 02 52 03 52 View of Neo from Madeira Lane Perfect for a Modern City Fringe Lifestyle Neo sits one block north of Khyber Pass Road across from Saint David’s Church in a pocket of new residential development. It looks north across the city centre towards the Waitemata Harbour and Hauraki Gulf. It is located at the intersection of Auckland’s top suburbs – Kingsland, Mount Eden, Newmarket and Parnell – and within walking distance of the CBD. In every direction it is surrounded by Auckland’s best amenities, activities and attractions. You will find Neo to be amazing value for such high-quality, architecturally- designed apartments in the heart of Auckland City. They are the perfect first home or investment property. 06 52 07 52 Dining at Ortolana, Britomart 08 52 09 52 Key Information 5-9 Madeira Lane, Podium garden Grafton, Auckland for residents Located in the Auckland Secure, covered parking Grammar and Auckland Girls Grammar Zones Views of the Sky Tower, Rangitoto Island and the Mix of studio, Waitemata Harbour 1 and 2 bedroom freehold apartments Timber floors and glass balustrades Architecture and interiors by apartment specialists, Leuschke Group Resource Consent issued Quality construction Developed by Sunny methods and materials Grafton Apartments, part of the Risland Group 10 52 11 52 10 Reasons to Choose Neo Purchasing a Neo 1. -

Item 24 Māori Naming of Parks and Places in the Waitematā Local Board Area

Waitematā Local Board Tranche 1 Park for Dual Naming # of Site Brief origin of name (254 characters Street Locality characters Source(s) (254 characters max) Detailed origin of name and source Description max) - source Basque Exmouth Eden Probably named after the Napoleonic 106 Truttman, L. (2012). Basque Park. Retrieved from Park Street Terrace Wars sea battle "Battle of the Basque https://timespanner.blogspot.com/2012/07/basque- Roads". park.html Bayfield West End Ponsonby Probably named for the road or school 135 Bayfield School Herne Bay. School history. Park Road West (also in the Herne Bay area). The Retrieved from https://hail.to/bayfield-school- school was established in 1886. herne-bay/publication/0ZjzXxA/article/eITZnNZ Costley Costley Freemans Probably named after Edward Costley, 100 Davenport, John C. (1990) Street names of Probably named after Edward Costely, an early Reserve Street Bay an early Auckland settler and one of the Auckland: their story. Auckland, N.Z.: Hodder & Auckland settler and one of the city's benefactors. He city's benefactors. Previously called Stoughton. gave money to establish a home for the elderly, to the William Street until 1883. Also called City library, art gallery, Auckland Museum, an orphan's Withain St (perhaps a misprint?) home and boys' institute. Previously called William Street until 1883. Also called Withain St (perhaps a misprint?) Source: Davenport, John C. (1990) Street names of Auckland: their story. Auckland, N.Z.: Hodder & Stoughton. Coxs Bay West End Westmere Presumably named after the Bay. Maori 67 Auckland City Council. (1994). Cox's Bay reserves Reserve Road name for the Bay is Opoutukeka/Opou. -

Restaurant Name

Restaurant Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City Name Postal Code Location 16 TUN 10-26 JELLICOE STREET WYNYARD QUARTER 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND 1947 EATERY 60 FEDERAL STREET AUCKLAND 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND 46 & YORK 46 PARNELL ROAD PARNELL 1052 CENTRAL AUCKLAND AMANO 68 TYLER STREET BRITOMART 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND ANDY'S BURGERS & BAR SKYCITY AUCKLAND CNR VICTORIA ST WEST & HOBSON ST AUCKLAND 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND ANGUS STEAK HOUSE 8 FORT LANE AUCKLAND 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND ANTOINE'S RESTAURANT 333 PARNELL RD PARNELL 1052 CENTRAL AUCKLAND ARCHIE'S RESTAURANT & PIZZERIA 61-73 DAVIS CRESCENT NEWMARKET 1023 CENTRAL AUCKLAND ARIA RESTAURANT AND BAR 128 ALBERT STREET AUCKLAND 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND AUGUSTUS 1 ST MARYS RD ST MARYS BAY 1011 CENTRAL AUCKLAND AZABU 26 PONSONBY ROAD PONSONBY 1011 CENTRAL AUCKLAND BADUZZI 10-26 JELLICOE STREET WYNYARD QUARTER 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND BANGKOK RESTAURANT 1 WELLESLEY STREET AUCKLAND 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND BASIL THAI 236 DOMINION ROAD SHOP 2 MOUNT EDEN 1024 CENTRAL AUCKLAND BEAST & BUTTERFLIES RESTAURANT 196-200 QUAY STREET AUCKLAND CENTRAL 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND BEDFORD SODA AND LIQUOR 4 BROWN ST SHOP 10 PONSONBY 1021 CENTRAL AUCKLAND BELLOTA SKYCITY AUCKLAND 91 FEDERAL ST AUCKLAND 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND BESOS LATINOS 39 ELLIOTT STREET SHOP M16 AUCKLAND 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND BIEN IZAKAYA 53B DAVIS CRESCENT NEWMARKET 1023 CENTRAL AUCKLAND BIG LITTLE GRILL 41 ELLIOTT ST AUCKLAND 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND BILLFISH CAFE 31 WESTHAVEN DR SHOP 3 ST MARYS BAY 1010 CENTRAL AUCKLAND BISTRO BAMBINA 268 PONSONBY RD PONSONBY -

DISTRICT PLAN CENTRAL AREA SECTION - OPERATIVE 2004 Page 1 Updated 19/03/2012 PART 14.10 - VICTORIA QUARTER

PART 14.10 - VICTORIA QUARTER CONTENTS PAGE VICTORIA QUARTER ............................................................................................ 4 14.10.1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 4 14.10.2 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT ISSUES ........................................ 4 14.10.3 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT OBJECTIVES AND POLICIES .... 6 14.10.4 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ................................ 10 14.10.5 ANTICIPATED ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS .......................... 11 14.10.6 RULES - ACTIVITIES ................................................................. 12 14.10.7 ASSESSMENT CRITERIA ......................................................... 15 14.10.8 RULES - DEVELOPMENT CONTROLS .................................... 23 14.10.9 DEFINITIONS ............................................................................. 28 14.10.10 REFERENCES ........................................................................... 28 Plan modification annotations - key Indicates where content is affected by proposed plan modification x. x Refer to plan modification folder or website for details. Indicates where the content is part of plan modification x, which is x subject to appeal. Underlined content to be inserted. Struck through content to be deleted. CITY OF AUCKLAND - DISTRICT PLAN CENTRAL AREA SECTION - OPERATIVE 2004 Page 1 updated 19/03/2012 PART 14.10 - VICTORIA QUARTER CITY OF AUCKLAND - DISTRICT PLAN Page 2See key on page 1 CENTRAL AREA SECTION - OPERATIVE 2004 of this section -

Current Locations of Interest in New Zealand 19 August Am

Current locations of interest in New Zealand 19 August am Auckland locations of interest Location name Address Day Times Date added Sumthin Dumplin 18 Wellesley Street East, Auckland Tuesday 3 August 1.45 pm - 2.00 pm 18-Aug Central, 1010 Lynn Mall 3058 Great North Road, New Lynn, Friday 6 August 6.00 pm - 7.30 pm 18-Aug Auckland, 0600 Mexico Britomart 23 Britomart Place, Auckland Central, Monday 9 August 5.55 pm - 8.15 pm 18-Aug 1010 Bus 97B Birkdale to Auckland CBD Bus 97B Tuesday 10 August 11.30 am - 12.00 pm 18-Aug St Pierre's Sushi Auckland CBD 20 Elliott Street, Auckland Central, Tuesday 10 August 1.00 pm - 1.15 pm 18-Aug Auckland 1010 The Warehouse Auckland CBD 21 Elliott Street, Auckland Central, 1010 Tuesday 10 August 1.15 pm - 1.30 pm 18-Aug Event Cinemas Queen Street 1/291 Queen Street, Auckland Central, Tuesday 10 August 1.30 pm - 4.00 pm 18-Aug 1010 Gongcha Bubble Tea 164 Queen Street, Auckland Central, Tuesday 10 August 1.45 pm - 1.55 pm 18-Aug 1010 St Pierres Sushi Elliot Street 20 Elliott Street, Auckland Central, Wednesday 11 August 11.30 am - 12.00 pm 18-Aug Auckland 1010 Event Cinemas Queen Street 1/291 Queen Street, Auckland Central, Wednesday 11 August 1.30 pm - 4.00 pm 18-Aug 1010 Avondale College 51 Victor Street, Avondale, Auckland Thursday 12 August 8.45 am - 3.15 pm 18-Aug 1026 Crumb Grey Lynn Ariki Street, Grey Lynn, Auckland, 1021 Thursday 12 August 10.00 am - 10.10 am 17-Aug Glasscorp Limited Albany 124 Bush Road, Rosedale, Auckland Thursday 12 August 12.30 pm - 1.00 pm 18-Aug 0632 Unique Hardware Rosedale