355–Ship Navy: Delivering the Right Capabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 52 April 2016 from the Editor

Editor – Edwin Hergert Volume 5 Issue 52 April 2016 Phone: (480)814-7339 Send Submissions to: [email protected] From the Editor: Submarine Warfare of World War II rare documentary The following is retrieved from the “American https://www.youtube.com/watch? Submariner” publication Volume 2016 Issue 1, page v=YQ4KmpdHUVs#t=4524.438 21. By permission from Editor , Charles (Chuck) Emmett U Boat Documentary ? Submarine ? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r- sq0nTaYdk#t=156.594 When asked about where and when you were really a submariner there is finally a legal answer we Submarine Pictures can give without losing a clearance. http://www.subasepearl.com/pages/Silent_Service_Photo_In dex “yes...on the sub I was on we did some of the stuff we did, and we didn't do some of the other stuff Haddo 604 Memories we did, because if we did it, it was secret, So we didn't do some of the other stuff we did because if we did do The “Big Angle” it, it was secret. So we really didn't do it. Even though we really did. But not really. Those medals me and my There are moments in every submariner’s life shipmates got that we didn't get for doing what we that will live forever in his memory. Although this story didn't do that we did. I really got those. Except not. But, has been told and retold many times over the years, it Yeah. That's because we never went where we were, bears re-telling every so often. -

The Future of Naval Aviation November 2014

The Evolving Future for Naval Aviation By Robbin Laird and Ed Timperlake Second Line of Defense November 2014 http://www.sldinfo.com h The Evolving Future of Naval Aviation 1 Table of Contents LESSONS LEARNED AT FALLON: THE USN TRAINS FOR FORWARD LEANING STRIKE INTEGRATION .......................................................................................................................... 2 REAR ADMIRAL MANAZIR, DIRECTOR OF AIR WARFARE (OPNAV N98) ..................................... 7 THE ROLE OF LIVE VIRTUAL TRAINING ................................................................................................. 8 THE IMPACT OF 5TH GEN ON FIGHTING IN THE EXPANDED BATTLESPACE .................................................. 12 RE-THINKING THE SEA BASE ............................................................................................................ 13 THE CARRIER AND JOINT AND COALITION OPERATIONS: SHAPING INVESTMENTS FOR THE FUTURE ............... 14 VICE ADMIRAL WILLIAM MORAN, DEPUTY CHIEF OF NAVAL OPERATIONS, (N1), FORMER DIRECTOR OF AIR WARFARE (OPNAV N98) ............................................................................. 15 THE TRANSITION ............................................................................................................................ 15 SHAPING INNOVATION .................................................................................................................... 16 THE COMING OF THE F-35 ............................................................................................................. -

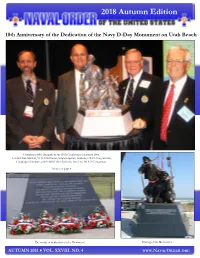

2018 Autumn Edition

2018 Autumn Edition 10th Anniversary of the Dedication of the Navy D-Day Monument on Utah Beach Unveiling of the Maquette at the SNA Conference in Jan uary 2006. L to R: Dean Mosher, NOUS Historian; Stephen Spears, sculptor; CAPT Greg Streeter, Campaign Chairman; and VADM Mike Kalleres, 1st Coast NOUS Companion. Article on page 4 The words of dedication on the Monument Placing of the Monument AUTUMN 2018 ● VOL. XXVIII, NO. 4 WWW.NAVALORDER.ORG COMMANDER GENERAL ’S REPORT TO THE ORDER 2018 Congress in San Antonio - What to On Saturday morning, 27 October, after a continental breakfast, remaining national officer reports will be made followed by a Look Forward to…or What You’re Missing presentation by citizen sailor, businessman and author, CAPT The Texas Commandery is hosting the 2018 Congress at the Mark Liebmann. Wyndam San Antonio Riverwalk from Wednesday, 24 The Admiral of the Navy George Dewey Award/Commander October through 27 October and assures us that our visit to General Awards Luncheon will recognize Mr. Marshall Cloyd, the Lone Star state will be most memorable. recipient of The Admiral of the Navy George Dewey Award. Although the Congress doesn’t officially start until Additionally, RADM Douglas Moore, USN (Ret.) will Wednesday, we will visit the National Museum of the Pacific receive the Distinguished Alumnus Award by the Navy Supply Corps Foundation. War (Nimitz Museum) in Fredericksburg, TX on Tuesday, 23 October. Similar to the National World War II Museum that After lunch a presentation will be made by James Hornfischer, one many of us visited during our 2015 Congress in New of the most commanding naval historians writing today. -

US Navy Program Guide 2012

U.S. NAVY PROGRAM GUIDE 2012 U.S. NAVY PROGRAM GUIDE 2012 FOREWORD The U.S. Navy is the world’s preeminent cal change continues in the Arab world. Nations like Iran maritime force. Our fleet operates forward every day, and North Korea continue to pursue nuclear capabilities, providing America offshore options to deter conflict and while rising powers are rapidly modernizing their militar- advance our national interests in an era of uncertainty. ies and investing in capabilities to deny freedom of action As it has for more than 200 years, our Navy remains ready on the sea, in the air and in cyberspace. To ensure we are for today’s challenges. Our fleet continues to deliver cred- prepared to meet our missions, I will continue to focus on ible capability for deterrence, sea control, and power pro- my three main priorities: 1) Remain ready to meet current jection to prevent and contain conflict and to fight and challenges, today; 2) Build a relevant and capable future win our nation’s wars. We protect the interconnected sys- force; and 3) Enable and support our Sailors, Navy Civil- tems of trade, information, and security that enable our ians, and their Families. Most importantly, we will ensure nation’s economic prosperity while ensuring operational we do not create a “hollow force” unable to do the mission access for the Joint force to the maritime domain and the due to shortfalls in maintenance, personnel, or training. littorals. These are fiscally challenging times. We will pursue these Our Navy is integral to combat, counter-terrorism, and priorities effectively and efficiently, innovating to maxi- crisis response. -

2016 NAVAL SUBMARINE LEAGUE CORPORATE MEMBERS 5 STAR LEVEL Bechtel Nuclear, Security & Environmental (BNI) (New in 2016) BWX Technologies, Inc

NAVAL SUBMARINE LEAGUE TH 34 ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM SPONSORS L-3 COMMUNICATIONS NEWPORT NEWS SHIPBUILDING-A DIVISION OF HUNTINGTON INGALLS INDUSTRIES GENERAL DYNAMICS—ELECTRIC BOAT GENERAL DYNAMICS—MISSION SYSTEMS HUNT VALVE COMPANY, INC. LOCKHEED MARTIN CORPORATION NORTHROP GRUMMAN NAVIGATION & MARITIME SYSTEMS DIVISION RAYTHEON COMPANY AECOM MANAGEMENT SERVICES GROUP BAE SYSTEMS BWX TECHNOLOGIES, INC. CURTISS-WRIGHT CORPORATION DRS TECHNOLOGIES, MARITIME AND COMBAT SUPPORT SYSTEMS PROGENY SYSTEMS, INC. TREADWELL CORPORATION TSM CORPORATION ADVANCED ACOUSTIC CONCEPTS BATTELLE BOEING COMPANY BOOZ ALLEN HAMILTON CEPEDA ASSOCIATES, INC. CUNICO CORPORATION & DYNAMIC CONTROLS, LTD. GENERAL ATOMICS IN-DEPTH ENGINEERING, INC. OCEANEERING INTERNATIONAL, INC. PACIFIC FLEET SUBMARINE MEMORIAL ASSOC., INC. SONALYSTS, INC. SYSTEMS PLANNING AND ANALYSIS, INC. ULTRA ELECTRONICS 3 PHOENIX ULTRA ELECTRONICS—OCEAN SYSTEMS, INC. 1 2016 NAVAL SUBMARINE LEAGUE WELCOME TO THE 34TH ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM TABLE OF CONTENTS SYMPOSIUM SPEAKERS BIOGRAPHIES ADM FRANK CALDWELL, USN ................................................................................ 4 VADM JOSEPH TOFALO, USN ................................................................................... 5 RADM MICHAEL JABALEY, USN ............................................................................. 6 MR. MARK GORENFLO ............................................................................................... 7 VADM JOSEPH MULLOY, USN ................................................................................. -

Bright Penny

T H E BRIGHT PENNY September 2002 A NEWSLETTER FOR MEMBERS OF THE USS BERKELEY (DDG -15) ASSOCIATION REUNION 2002 - BE THERE! The Berkeley Association’s reunion, October 17 -20, 2002, promises to be one SKIPPER IN THE SPOTLIGHT of the best we have had. To date a total of 78 former crew members have plans to Born in 1929, Rear Admiral attend. Scheduled events include the Smedberg graduated from the Naval Academy with the Class of 1951. Welcome Reception on During the following 31 years o n Friday and the Banquet active duty he followed the typical on Saturday . The pattern of a Surface Warfare Officer. Hospitality Suite will He had five at -sea commands: an LST be open on Thursday as a Lieutenant, a Frigate as a from 1600 to 2000, Lieutenant Commander, the guided missile destroyer USS BERKELEY from Friday from 1600 to January 1966 to July 1967 as a 2000 and Saturday Commander, a Destroyer Squadron as from 1400 to 1600. a Captain, and the Forrestal Carrier Battle Group as a Rear Admiral. Ray Bartlett There will be a memorabilia table set Between sea duty tours, he served five separate tours on the Chief of up in the hospitality room with the Naval Operations’ staff in the Pentagon. Association’s collection of cruise books. A As a Captain, he also served as videotape of the decommissioning Operations Officer on the SIXTH FLEET ceremony will also be available for in the Mediterranean and as the viewing. In addition, items from the ship’s Assistant Executive and Senior Aide to store will be available for purchase. -

Department of the Navy Fiscal Year 2017 Navy Annual Financial Report

ACCOUNTABILITY TO AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY FISCAL YEAR 2017 ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT People Processes Capabilities FISCAL YEAR 2017 DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT A Marine conducts preflight inspections during training. (U.S. Navy photo by Cpl. James Guillory/Released) An Airman reattaches fasteners on the tail rotor of an MH-60R Sea Hawk helicopter. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Andrew J. Sneeringer/Released) TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from the Secretary of the Navy 3 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 4 Message from the Assistant Secretary of the Navy (Financial Management & Comptroller) 47 Department of the Navy Principal Statements 61 Department of the Navy Required Supplementary Stewardship Information 97 Department of the Navy Required Supplementary Information 105 Department of the Navy Other Information 113 Navy Working Capital Fund Audit Opinions 117 Navy Working Capital Fund Principal Statements 127 Navy Working Capital Fund Required Supplementary Information 153 Navy Working Capital Fund Other Information 155 Appendix 157 A CH-53E Super Stallion helicopter assigned to Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 463 carries a Humvee during an external lift training. (U.S. Navy photo by Lance Cpl. Jesus Sepulveda/Released) People Processes Capabilities 2 DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY FISCAL YEAR 2017 ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT MESSAGE FROM THE SECRETARY OF THE NAVY 3 NOVEMBER 2017 RICHARD V. SPENCER As the nation’s forward global force, the Navy and Marine Corps are fully deployed, continuously present afloat and ashore, promoting and protecting the national interests of the United States. We must always be ready to deliver the fight in a moment’s notice. -

Rules for Extensions to Change by Katie Suich Orders to Places That Require Less Than 24 Into

. Mayport Ships Training Takes Innovative Initiatives, Pages 4-5 2008 CHINFO Award Winner ������������������� ����������������������� ���������������������� ��������������������������� Rules For Extensions To Change By Katie Suich orders to places that require less than 24 into. NPC also has procedures in place Navy Personnel Command Public Affairs Office ��������������� months, such as Diego Garcia and unac- to handle unique situations that might The Navy will change the Short Term companied tours. require more than two extensions per Extension (STE) policy Oct. 1, affecting ����������� *All other obligated-service require- contract. obligated service (OBLISERV) rules for ments will remain the same. *Extension policy for Sailors taking enlisted personnel. ����������������� The maximum number of short-term individual augmentee/global war on ter- Labor Day According to NAVADMIN 242/09, the ������������ extensions that a Sailor may now use reason for the change is that the Navy will be two per contract. The length rorism support assignments (IA/GSA) Hours For MWR has noticed during the past several years ����������������������� of an extension will be limited to 23 orders remains the same. Once they the number of STEs has risen substan- months, and the total of all extensions have completed the GSA/IA assignment, In recognition of Labor tially. ���������� cannot exceed 24 months. Other rules they will fall under current detailing and Day on Sept. 7, the following “The impact of this change is that include: extension policies MWR facilities will be closed: more Sailors will be directed toward Currently, a Sailor has to obligate for *Extensions counting against the Sailors choosing not to obligate for Auto Skills reenlistments, said Master Chief Petty 12 months when they receive orders to Sailor’s two-extension limit are those Bingo the required 24 months but have more Officer of the Navy Rick West. -

Military Medals and Awards Manual, Comdtinst M1650.25E

Coast Guard Military Medals and Awards Manual COMDTINST M1650.25E 15 AUGUST 2016 COMMANDANT US Coast Guard Stop 7200 United States Coast Guard 2703 Martin Luther King Jr Ave SE Washington, DC 20593-7200 Staff Symbol: CG PSC-PSD-ma Phone: (202) 795-6575 COMDTINST M1650.25E 15 August 2016 COMMANDANT INSTRUCTION M1650.25E Subj: COAST GUARD MILITARY MEDALS AND AWARDS MANUAL Ref: (a) Uniform Regulations, COMDTINST M1020.6 (series) (b) Recognition Programs Manual, COMDTINST M1650.26 (series) (c) Navy and Marine Corps Awards Manual, SECNAVINST 1650.1 (series) 1. PURPOSE. This Manual establishes the authority, policies, procedures, and standards governing the military medals and awards for all Coast Guard personnel Active and Reserve and all other service members assigned to duty with the Coast Guard. 2. ACTION. All Coast Guard unit Commanders, Commanding Officers, Officers-In-Charge, Deputy/Assistant Commandants and Chiefs of Headquarters staff elements must comply with the provisions of this Manual. Internet release is authorized. 3. DIRECTIVES AFFECTED. Medals and Awards Manual, COMDTINST M1650.25D is cancelled. 4. DISCLAIMER. This guidance is not a substitute for applicable legal requirements, nor is it itself a rule. It is intended to provide operational guidance for Coast Guard personnel and is not intended to nor does it impose legally-binding requirements on any party outside the Coast Guard. 5. MAJOR CHANGES. Major changes to this Manual include: Renaming of the manual to distinguish Military Medals and Awards from other award programs; removal of the Recognition Programs from Chapter 6 to create the new Recognition Manual, COMDTINST M1650.26; removal of the Department of Navy personal awards information from Chapter 2; update to the revocation of awards process; clarification of the concurrent clearance process for issuance of awards to Coast Guard Personnel from other U.S. -

Benefits Tion with Onal Jour- Evelop- Areness

Seminar Hosts Naval Submarine League The primary mission of the Naval Submarine League is to promote awareness of the importance of submarines to U.S. national security. The Naval Submarine League is a professional organization for submariners and submarine supporters. Benefits of Naval Submarine League membership include association with a dedicated group of submarine professionals, a professional jour- nal – The Submarine Review, information on submarine develop- ments and issues to assist members in creating public awareness of submarine capabilities and value to U.S. defense, a forum for an exchange of thoughts on submarine matters, and an invitation to the Annual Symposium. The Naval Submarine League is a 501(c)3 non-profit founded in 1982. For more details and how to join, visit the League’s web- site www.navalsubleague.org or call (703) 256-0891. Naval Historical Foundation Founded in 1926, the Naval Historical Foundation is dedicated to preserving and honoring the legacy of the Sailors who came before us. We know that passing this legacy on will serve to educate and inspire the generations that will follow. The Naval Historical Foundation raises funds and supervise the construc- tion of cutting edge museum exhibits. We encourage students and teachers with educational programs, prizes, and fellowships. We work tirelessly to ensure that America’s great naval history is proudly remembered. For more details about the services we provide and how to join, visit www.navyhistory.org. or call (202) 678-4333. Welcoming Remarks Rear Admiral John B. Padgett III, USN (Ret.) 41 For Freedom President and Chief Executive Officer Naval Submarine League Introduction and Program Summary Dr. -

Admiral Thomas C. Hart and the Demise of the Asiatic Fleet 1941 – 1942

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2014 Admiral Thomas C. Hart And The eD mise Of The Asiatic Fleet 1941 – 1942 David DuBois East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation DuBois, David, "Admiral Thomas C. Hart And The eD mise Of The Asiatic Fleet 1941 – 1942" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2331. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2331 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Admiral Thomas C. Hart And The Demise Of The Asiatic Fleet 1941 – 1942 A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History by David DuBois May 2014 Dr. Emmett M. Essin III, Chair Dr. Stephen G. Fritz Dr. John M. Rankin Keywords: Admiral Thomas C. Hart, U.S. Navy WWII, Asiatic Fleet, ABDA, USS Houston, Battle of the Java Sea ABSTRACT Admiral Thomas C. Hart And The Demise Of The Asiatic Fleet 1941 – 1942 by David DuBois Admiral Thomas C. Hart And The Demise Of The Asiatic Fleet 1941 – 1942 is a chronicle of the opening days of World War II in the Pacific and the demise of the U.S. -

Smoky Mountain Base, Tn Ussvi

SMOKY MOUNTAIN BASE, TN USSVI OUR “ToOR- Honor Those Who Serve, Past, Present, and Future”. GANIZATI“The USSVI Submariner’s Creed” To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who gave their lives in the pursuit of their duties while serving their country. That their dedication, deeds, and supreme sacrifice be a constant source of motivation toward greater accomplishments. We pledge loyalty and patriotism to the United States of America and its Constitution. OUR ORGANIZATION OUR FOUNDERS OUR BROTHERHOOD Our Mission SNORKEL EXHAUST INDEX The organization will engage in various May & June 2019 projects that will bring about the perpetual remembrance of those shipmates who INDEX OF WHO WE ARE AND WHAT’S IN THIS ISSUE 1 have given the supreme sacrifice. The SMOKY MOUNTAIN BASE OFFICERS 2 organization will also endeavor to educate all third parties it comes in contact with SMB MEETINGS, NEW MEMBERS, CALANDARS AND LOCAL INFO 3 about the services our submarine brothers LOCAL & USSVI HAPPENINGS, ADS AND VETERANS INFORMATION 4 performed and how their sacrifices made possible the freedom and lifestyles we BASE OFFICERS REPORTS, SUMMER PICNIC INFO 5 enjoy today. SECRETARY’S REPORT AND TOLLING OF THE BELL FOR MAY/JUN 6 PRE WW-II AND LOST BOATS OF MAY 7 LOST BOATS OF JUNE AND POST WW-II 8-10 Scheduled Meetings POST WW-II LOST BOATS AND SALVAGING OF THE SQUALUS 11 MUSIC IN THE MOUNTAINS PARADE 12 Monthly meetings are scheduled for the BILL SMITH OBIT AND SMB FOUNDERS & HONOR GUARD REQUEST 13 3rd Thursday of each month at: BOONDOGGLE OF THE MONTH - PT BOAT (PART 1) 14 GOLDEN CORRAL BOONDOGGLE OF THE MONTH - PT BOAT (PART 2) 15 6612 CLINTON HIGHWAY, APPLICATION FOR MEMBERSHIP IN USSVI 16 KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE Dinner & Social Hour @ 1800 Follow us on Facebook at: Meeting @ 1900 Smoky-Mountain-Submarine-Veterans-273222054302 SMOKY MOUNTAIN BASE OFFICERS BASE COMMANDER BASE VICE-COMMANDER Marlin E.