JULY Issue 2020.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commander Abu Taher Mohammad Shahid Ahsan

Deputy General Manager (Electrical) Commander Abu Taher Mohammad Shahid Ahsan,(L), psc, BN (P NO-1150) was born on 05 November of 1975 in a noble muslim family belonging to Faridpur district, kajikanda thana. He passed out from Pabna Cadet College keeping a meritorious academic back ground and Joined Bangladesh Navy on 01 July 1994. After passing out from BNA, he was sent to undergo Bsc (hns) in Electrical & Electronics Engineering) in CUET (Chittagong University of Engineering & Technology). He joined BN fleet in 2001 as an Electrical officer after graduation. He did his JSC in BNA in 2006 and Long Electrical Specialization Course in BNS Shaheed Moazzam, Kaptai in 2007. He did his 2nd Specialization Course in INS Valsura, Gujrat, India during 2009-2010 and earned good name for BN by his extraordinary result. He is a proud Mirpurian graduate from Mirpur Staff College. In the journey of his naval career, he served onboard numerous ships & crafts of BN in the capacity of Electrical officer, specially oil tanker, hydrography vessel, mine sweepers, Large Patrol Craft, Chinese Frigate, British frigates, American Frigate and finally on board BNS Bangabandhu and contributed immensely in mid-life up gradation of BNS Bngabandhu. He served as Instructor and Course Officer of Long Electrical Course in BNS Shaheed Moazzam and trained numerous mid level officers. He earned sound knowledge about defense procurement while serving one year as ADP (Asst. Director of Purchase) in DGDP in 2012. He served BN Dockyard two times as OIC Heavy Electrical workshop, SO(O) to CSD, DGM (L), DGM (Ord), INDUSTRIAL ENGINEER and GM(Yard service). -

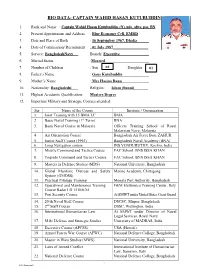

Bio Data- Captain Wahid Hasan Kutubuddin

BIO DATA- CAPTAIN WAHID HASAN KUTUBUDDIN 1. Rank and Name : Captain Wahid Hasan Kutubuddin, (N), ndc, afwc, psc, BN 2. Present Appointment and Address : Blue Economy Cell, EMRD 3. Date and Place of Birth : 16 September 1967, Dhaka 4. Date of Commission/ Recruitment : 01 July 1987__________________ 5. Service: BangladeshNavy Branch: Executive 6. Marital Status :Married 7. Number of Children : Son 02 Daughter 01 8. Father’s Name : Gaus Kutubuddin 9. Mother’s Name : Mrs Hasina Banu 10. Nationality: Bangladeshi Religion: ___Islam (Sunni)_______ 11. Highest Academic Qualification: Masters Degree 12. Important Military and Strategic Courses attended: Ser Name of the Course Institute / Organization 1. Joint Training with 15 BMA LC BMA 2. Basic Naval Training (1st Term) BNA 3. Basic Naval Course in Malaysia Officers Training School of Royal Malaysian Navy, Malaysia 4. Air Orientation Course Bangladesh Air Force Base ZAHUR 5. Junior Staff Course (1992) Bangladesh Naval Academy (BNA) 6. Long Navigation course INS VENDURUTHY, Kochin, India 7. Missile Command and Tactics Course FAC School, BNS ISSA KHAN 8. Torpedo Command and Tactics Course FAC School, BNS ISSA KHAN 9. Masters in Defence Studies (MDS) National University, Bangladesh 10. Global Maritime Distress and Safety Marine Academy, Chittagong System (GMDSS) 11. Practical Pilotage Training Mongla Port Authority, Bangladesh 12. Operational and Maintenance Training GEM Elettronica Training Center, Italy Course Radar LD 1510/6/M 13. Port Security Course At SMWT under United States Coast Guard 14. 20 th Naval Staff Course DSCSC, Mirpur, Bangladesh 15. 2nd Staff Course DSSC, Wellington, India 16. International Humanitarian Law At SMWT under Director of Naval Legal Services, Royal Navy 17. -

ANNELIES ILENA Upon Arrival in the Port of Ijmuiden Last Friday – Photo : Piet Sinke (C)

DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2013 – 146 Number 146 *** COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS *** Sunday 26-05-2013 News reports received from readers and Internet News articles copied from various news sites. The ISKES tug SATURNUS assisting worlds largest stern trawler the KW 174 ANNELIES ILENA upon arrival in the port of Ijmuiden last Friday – photo : Piet Sinke (c) Distribution : daily to 25900+ active addresses 26-05-2013 Page 1 DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2013 – 146 Your feedback is important to me so please drop me an email if you have any photos or articles that may be of interest to the maritime interested people at sea and ashore PLEASE SEND ALL PHOTOS / ARTICLES TO : [email protected] If you don't like to receive this bulletin anymore : To unsubscribe click here (English version) or visit the subscription page on our website. http://www.maasmondmaritime.com/uitschrijven.aspx?lan=en-US EVENTS, INCIDENTS & OPERATIONS 24-05-2013 : Celebrity cruises ship CELEBRITY MILLENNIUM outbound in Vancouver harbour Photo : Robert Etchell (c) Maersk rate hikes hitting the high notes Do we sense a touch of desperation from the executive corridors of Maersk Line as the Triple-E delivery dates approach? Maersk Line boss Nils Smedegaard Andersen was in a confident mood after his carrier posted a decent US$204 million profit in the first quarter. Making a profit when Asia-Europe is a disaster and many other carriers are wallowing in red ink is impressive enough, but the Maersk CEO raised eyebrows when he addressed the rates issue. He told Reuters he had "no doubt" the carrier could increase rates from their current level of $730 to $1,481 per TEU on July 1. -

Armed Forces War Course-2013 the Ministers the Hon’Ble Ministers Presented Their Vision

National Defence College, Bangladesh PRODEEP 2013 A PICTORIAL YEAR BOOK NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE MIRPUR CANTONMENT, DHAKA, BANGLADESH Editorial Board of Prodeep Governing Body Meeting Lt Gen Akbar Chief Patron 2 3 Col Shahnoor Lt Col Munir Editor in Chief Associate Editor Maj Mukim Lt Cdr Mahbuba CSO-3 Nazrul Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Family Photo: Faculty Members-NDC Family Photo: Faculty Members-AFWC Lt Gen Mollah Fazle Akbar Brig Gen Muhammad Shams-ul Huda Commandant CI, AFWC Wg Maj Gen A K M Abdur Rahman R Adm Muhammad Anwarul Islam Col (Now Brig Gen) F M Zahid Hussain Col (Now Brig Gen) Abu Sayed Mohammad Ali 4 SDS (Army) - 1 SDS (Navy) DS (Army) - 1 DS (Army) - 2 5 AVM M Sanaul Huq Brig Gen Mesbah Ul Alam Chowdhury Capt Syed Misbah Uddin Ahmed Gp Capt Javed Tanveer Khan SDS (Air) SDS (Army) -2 (Now CI, AFWC Wg) DS (Navy) DS (Air) Jt Secy (Now Addl Secy) A F M Nurus Safa Chowdhury DG Saquib Ali Lt Col (Now Col) Md Faizur Rahman SDS (Civil) SDS (FA) DS (Army) - 3 Family Photo: Course Members - NDC 2013 Brig Gen Md Zafar Ullah Khan Brig Gen Md Ahsanul Huq Miah Brig Gen Md Shahidul Islam Brig Gen Md Shamsur Rahman Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Brig Gen Md Abdur Razzaque Brig Gen S M Farhad Brig Gen Md Tanveer Iqbal Brig Gen Md Nurul Momen Khan 6 Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army 7 Brig Gen Ataul Hakim Sarwar Hasan Brig Gen Md Faruque-Ul-Haque Brig Gen Shah Sagirul Islam Brig Gen Shameem Ahmed Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh -

Anti Armour Joint Survivability Dismounted

COVER-MAY 13:AMR 6/11/13 1:37 PM Page 1 VOLUME 21/ISSUE 3 MAY 2013 US$15 A S I A P A C I F I C ’ S L A R G E S T C I R C U L A T E D D E F E N C E M A G A Z I N E ANTI ARMOUR SUBMARINE WARFARE JOINT SURVIVABILITY SPECIAL MISSION DISMOUNTED ISTAR AIRCRAFT NAVAL DIRECTORY SINGAPORE MILITARY www.asianmilitaryreview.com GMB_2013_ISR_AsianMilitaryRev_April_002_Print.pdf 1 4/18/13 2:53 PM Content & Edit May13:AMR 6/11/13 6:03 PM Page 3 MAY 2013 ContentsContentsVOLUME 21 / ISSUE 3 06 Front Cover Photo: The fuel cell powered HDW Class 212A submarines have been in service with the German Navy since 2005. A The Wide Blue Yonder second batch of two boats in currently under construction Martin Streetly at ThyssenKrupp Marine As a region dominated by the vastnesses of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, Systems in Kiel, Germany © the Asia-Pacific nations have always had a strong interest in the ability to police ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems and monitor their national and economic regional interests 14 Singapore’s 48 Defence Stance Gordon Arthur Singapore may be the smallest country in SE Asia but it has 54 region’s most able military. Perched on tip of Malay Peninsula Survivability: Submarine warfare where Malacca and Singapore Stopping Enemy and upgrades Straits converge, Singapore Fires On Sea achieves world’s 4th highest Ted Hooton A century ago naval power was defence expenditure per capita AndLand counted in battleships, but the Gordon Arthur modern arbiter of naval power Survivability on the battlefield is consists of invisible battleships 40 important… obviously! Threats submarines which have played a 23 come from multiple directions major role in shaping modern Asia and in many shapes, so the per- and are likely to continue to tinent question is how to protect do so. -

Asian Defence & Diplomacy

Asian Defence & VOL 19 NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2012 MICA (P) 173/06/2012 SINGAPORE $10 Diplomacy REST OF THE WORLD US$20 06 Special Report China | 12 China’s Airforce | 17 Fleet Management 22 Gunfire Locators | 28 Fighter Radar | 34 Anti-Ship Missiles 240mm Live 275mm Trim 295mm Bleed The multi-role Super Hornet fulfills immediate needs for an advanced, net-enabled fighter with interoperability, maritime awareness and battle-management capabilities. It’s a world-class solution that builds on a partnership with Boeing—and our longstanding commitment to Malaysia’s future that’s stronger than ever. 180mm Live 210mm Trim 220mm Bleed Job Number: BOEG_BDS_F18_2104M_A Approved Scale: 1.0" = 1" Client: Boeing Product: Boeing Defense Space & Security Date/Initials Date: 9/17/10 GCD: P. Serchuk file Name: BOEG_BDS_F18_2104M_A Creative Director: P. Serchuk Output printed at: 100% Art Director: J. Alexander Fonts: Helvetica (Bold), Helvetica (Plain), Helvetica 65 Copy Writer: P. Serchuk Media: Asian Defence & Diplomacy Print Producer: Space/Color: Full Page–4-Color–Bleed Account Executive: D. McAuliffe 3C 50K Live: 180mm x 240mm Client: Boeing 50C 4C 41M Trim: 210mm x 275mm Proof Reader: 41Y Bleed: 220mm x 295mm Legal: Production Artist: S. Bowman Traffic Manager: Traci Brown 0 25 50 75 100 Retoucher: Digital Artist: Art Buyer: Vendor: Schawk PUBLICATION NOTE: Guideline for general identification only. Do not use as insertion order. Material for this insertion is to be examined carefully upon receipt. If it is deficient or does not comply with your requirements, please contact: Print Production at 310-601-1485. Frontline Communications Partners 1880 Century Park East, Suite 1011, Los Angeles, CA 90067 Client - Frontline Job # - 118583 Ver. -

A Professional Journal of National Defence College Volume 16

A Professional Journal of National Defence College Volume 16 Number 1 June 2017 National Defence College Bangladesh EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Patron Lieutenant General Chowdhury Hasan Sarwardy, BB, SBP, BSP, ndc, psc, PhD Editor-in-Chief Air Vice Marshal M Sanaul Huq, GUP, ndc, psc, GD(P) Editor Colonel A K M Fazlur Rahman, afwc, psc Associate Editors Group Captain Md Mustafizur Rahman, GUP, afwc, psc, GD(P) Lieutenant Colonel A N M Foyezur Rahman, psc, Engrs Assistant Editors Lecturer Farhana Binte Aziz Assistant Director Md Nazrul Islam ISSN: 1683-8475 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electrical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by the National Defence College, Bangladesh Design & Printed by : ORNATE CARE 87, Mariam Villah (2nd floor), Nayapaltan, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh Cell: 01911546613, E mail: [email protected] DISCLAIMER The analysis, opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NDC, Bangladesh Armed Forces or any other agencies of Bangladesh Government. Statement, fact or opinion appearing in NDC Journal are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by the editors or publisher. III CONTENTS Page College Governing Body vi Vision, Mission and Objectives of the College vii Foreword viii Editorial ix Faculty and Staff x Abstracts xi Population of Bangladesh: Impact -

Brings the Latest Technology and Capabilities to the 7Th Fleet

SURFACE SITREP Page 1 P PPPPPPPPP PPPPPPPPPPP PP PPP PPPPPPP PPPP PPPPPPPPPP Volume XXXI, Number 2 August 2015 “Rebalance” Brings the Latest Technology and Capabilities to the 7th Fleet An Interview with RDML Charlie Williams, USN Commander, Logistics Group Western Pacific / Commander, Task Force 74 (CTF 73) / Singapore Area Coordinator Conducted by CAPT Edward Lundquist, USN (Ret) What’s important about the Asia-Pacific area of operations (AOR), country we tailor what we bring in CARAT to the needs and capacity and how does your command fit into the “rebalance” to the Pa- of our partners. Here in Singapore, CARAT Singapore is a robust cific, or the so-called “Pacific Pivot.” varsity-level exercise. It typically features live-fire, surface-to-air Looking strategically at the AOR, the Indo-Asia-Pacific region is on missiles and ASW torpedo exercises and we benefit and gain great the rise; it’s become the nexus of the global economy. Almost 60 value from these engagements. With other CARAT partner na- percent of the world’s GDP comes from the Indo-Asia-Pacific na- tions, we focus our training on maritime interdiction operations, or tions, amounting to almost half of global trade, and most of that humanitarian assistance and disaster response, and make it more commerce runs through the vital shipping lanes of this region. applicable to the country’s needs and desires. Another exercise that compliments CARAT, yet Moreover, more than 60 with a very different focus, is percent of the world’s SEACAT (Southeast Asia Co- population lives in the operation And Training). -

Full Page Photo

Jack Hunter From: Carl Grossman <[email protected]> Sent: Friday, September 14, 2012 6:20 AM To: Jack Hunter Subject: Re: JARVIS Stories On Thu, Sep 13, 2012 at 1:31 PM, Jack Hunter <[email protected]> wrote: This is your chance to share the history with the CO. Jack: Here is a Jarvis story: We were out in Guam on a West Pac. The Captain and about 15 to 20 of the crew had to go to Honolulu for a drug trial, for a drug bust we made on our previous patrol. (Another interesting story). The last thing the Captain told the XO get the ship underway tomorrow and take the Jarvis to Midway and we will meet you there. Simple enough order. Shortly after getting underway, the Exxon Valdez ran aground. The cutter (forgot which one) that was doing a North Pac fishing law enforcement patrol was diverted to be On-Seen-Commander. Meanwhile Jarvis was diverted to finish the fishery patrol leaving the Captain and others Stranded in Honolulu. Luckily they did not head to Midway before the diversion. The QM's scrambled to get our Alaskan charts up to date, as well as the rest of the ship getting ready for cold Alaska not the warm waters of the tropical Pacific. Ten days later, the Captain and crew met up with the ship in Adak, The Captain said to the XO "Can I have my ship back." An interesting highlight was the Jewish personnel prepared A Passover Seder. About 15 people Jewish and Non-Jewish attended the event. -

Car Loan Final List of Officer by LPR Seniority.Xlsx

RESTRICTED LIST OF OFFICERS LT CDR & ABOVE ( SENIORITY AS PER DATE OF RETIREMENT Wef-27 JULY 2020) Ser Rank & Name P No Billet / Appointment Age Limit 1 Lt Cdr M Golam Farooq, (SD)(R), BN 1563 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / EO 8/1/2020 2 Cdre Mohammad Rashed Ali, (TAS), NGP, ndc, psc, BN 535 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / CHINA FRIGATE (TYPE 053H3) / Proj Offr&Overall IC 25-08-2020 3 Cdre Syed Maksumul Hakim, (ND), BSP, ndc, ncc, psc, BN 464 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / Embassy of Bangladesh / Defense Advisor-Sri Lanka 27-08-2020 4 Cdre Mohammed Jahangir Alam, (E), NUP, ndc, psc, BN 465 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / Payra Port Authority / Chairman-PPA 18-09-2020 5 Cdre Mohammad Monirul Islam, (S), OSP, PCGMS, psc, BN 513 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / Defense and Strategic Studies Course, China 29-09-2020 6 Cdr Mohammad Shahed Karim, (C), BN 780 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / Embassy of Bangladesh / Asst Defense Attache-China 10/25/2020 7 Lt Cdr G Uttam Kumar, (SD)(R), BN 1722 BNS TITUMIR / MTO 10/30/2020 8 Cdre Abu Mohammad Quamrul Huq, (ND), NGP, ndc, afwc, psc, BN 473 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Maritime University / Treasurer 01-12-2020 9 Cdre Sheikh Mahmudul Hassan, (H), NPP, aowc, psc, BN 539 BNS ISSA KHAN / CHO & BNHOC / Chief Hydrographer 31-12-2020 10 Capt Masuq Hassan Ahmed, (G), PPM, psc, BN 590 BNS ISSA KHAN / Marine Fisheries Academy / Principal 31-12-2020 11 Instr Cdr Sharif Mostafa Shamim, (G), BN 1372 BNS HAJI MOHSIN / NHQ/DNAI&S / Additional 01-01-2021 12 Cdr Mohammad Ismail, (S), BN 787 BNS SHEIKH MUJIB / ADMIN DHAKA / Principal- Anchorage 04-01-2021 13 Lt Cdr Ferdous -

Canara Bank Po & Esic Sso Mains Capsule

aa Is Now In CHENNAI | MADURAI | TRICHY | SALEM | COIMBATORE | CHANDIGARH | BANGALORE |ERODE | NAMAKKAL | PUDUCHERRY |THANJAVUR |TRIVANDRUM | ERNAKULAM |TIRUNELVELI |VELLORE | www.raceinstitute.in | www.bankersdaily.in CANARA BANK PO & ESIC SSO MAINS CAPSULE Exclusively prepared for RACE students Chennai: #1, South Usman Road, T Nagar. | Madurai: #24/21, Near MapillaiVinayagar Theatre, Kalavasal. | Trichy: opp BSNL office, Juman Center, 43 Promenade Road, Cantonment. | Salem: #209, Sonia Plaza / Muthu Complex, Junction Main Rd, State Bank Colony, Salem. | Coimbatore #545, 1st floor, Adjacent to SBI (DB Road Branch),DiwanBahadur Road, RS Puram, Coimbatore| Chandigarh| Bangalore|Erode |Namakkal |Puducherry |Thanjavur| Trivandrum| Ernakulam|Tirunelveli | Vellore | H.O: 7601808080 / 9043303030 | www.raceinstitute.in Chennai RACE Coaching Institute Pvt Ltd CANARA & ESIC MANINS CAPSULE S.NO TOPICS PAGE NO 1. BANKING & BUSINESS 1 2. RANKING & INDEXES TAKEN BY VARIOUS ORGANISATIONS 27 3. NATIONAL NEWS 39 4. NATIONAL SUMMITS 76 5. STATES IN NEWS 88 6. INTERNATIONAL NEWS 115 7. LIST OF AGREEMENTS / MOU’S SIGNED BY 130 INDIA WITH VARIOUS COUNTRIES 8. INTERNATIONAL SUMMITS 137 9. APPOINTMENTS IN NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL 146 10. AWARDS & HONOURS 163 R.A.C.E 11. LIST OF VARIOUS COMMITTEES AND ITS HEAD 189 12. LOAN SANCTIONED BY NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL BANK 195 (APRIL – NOVEMBER 2018) 13. MILITARY, AIR, NAVY EXERCISES CONDUCTED BY 198 VARIOUS COUNTRIES 14. SPORTS NEWS 200 15. BOOKS AND AUTHORS 243 16. IMPORTANT EVENTS OF THE DAYS 246 17. OBITUARY -

The Navy Vol 63 Part 2 2001

TOMAHAWK FOR COE LINS? JULY - SEPTEMBER 2001 including GST) www netspace net .au/-navyleag VOLUlm 63 NO. 3 The Magazine of the Mi league of Australia DD-21; \ JUT 21st century w*^ Dreadnought *\ h Australia's Leading Naval Magazine Since I9JS THE NAVY llu I liium i>l Vnsli.ili.i Join The Navy League of Australia FEDERAL COUNCIL l*utnm in Chief: His Excellency. The Governor General. Volume 63 No. 3 President: Graham M Hams. RID See centre section for how. Vice-Presidents: RADM AJ Robertson. AO. DSC. RAN (Rid): John Bud. CDRE HJ.P. Adams. AM. RAN (Rtdl. CAPT H A Josephs. AM. RAN (Rldi Contents Hon. Secretary: Ray C<*bov. PO B«»\ 309. Ml Waveriey. Vic 3149. Telephone: (03)9888 1977. Fax: (03)9888 1083 TOMAHAWK FOR COLLINS? NEW SOUTH WAI.KS DIVISION By Dr Lee Willelt Page 4 l*atnm: Her Excellency . The Governor of New South Wales. President: R O Albert. AO. RID. Rl> AUSTRALIA'S MARITIME DOCTRINE Hon. Secretary: J C J Jeppesen. OAM. RID. GPO Box 1719. Sydney. NSW IM3 Telephone: (02) 913: 2144. Pax: ((C) 9132 8383. - Voyager' PARTI Page 8 VICTORIAN DIVISION DD-21; THE 2IST CENTURY Patnm: I lis Excellency. The Governor of Victoria. President: J M Wilkms. RID DREADNOUGHT Hon. Secretary : Gavan Bum. PO Box 1303. Box Hill. Vic 3128 Telephone: (03)9841 8570.1;ax: (03)9841 8107 By Sebastian Mathews Page 2(1 photographic, U.V. stabilised, Fmail: qircsC" o/cmail.cumaii Membership Secretary: I CDR Tom Kilhum MBE VRD THEY MUST BE STURDY Telephone: (03)9560 9927.