Dirty Skirts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol 25 / No. 2 / November 2017 Volume 24 Number 2 November 2017

1 Vol 25 / No. 2 / November 2017 Volume 24 Number 2 November 2017 Published by the discipline of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Self-portrait with projection, October 2017, img_9723 by Rodell Warner Anu Lakhan (copy editor) Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] OR Ms. Angela Trotman Department of Language, Linguistics and Literature Faculty of Humanities, UWI Cave Hill Campus P.O. Box 64, Bridgetown, BARBADOS, W.I. e-mail: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTION RATE US$20 per annum (two issues) or US$10 per issue Copyright © 2017 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Lisa Outar Ian Strachan BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. Edited by full time academics and with minimal funding or institutional support, the Journal originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. -

University of Miami Coral Gables, FL 33124-4632

Sandra Pouchet Paquet, Ph.D. Professor Emerita, Department of English, University of Miami Coral Gables, FL 33124-4632 Email [email protected] Curriculum Vitae Standard Format 1. Date: July 2013 PERSONAL 2. Name: Sandra Pouchet Paquet HIGHER EDUCATION 3. Institutional (institution; degree; date conferred): University of Connecticut, Storrs; Ph.D. in English; 1976 University of Connecticut, Storrs; M.A. in English; 1971 Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart, Purchase; B.A. (Honors) in English, 1967 4. Certification, licensure (description; board or agency; dates): Spanish 3-Day Mini-Mersion Program, May 18-20, 2007. EXPERIENCE 5. Academic (institutions; rank/status; dates): University of Miami, Professor; 2002-2010 University of Miami; Associate Professor; 1992-2002 University of Miami; Director, Caribbean Writers Summer Institute, 1992-1997 University of Pennsylvania; Assistant Professor; 1985-1992 University of Hartford; Assistant Professor; 1977-85 Director of Black Studies, 1977-79 University of the West Indies, Mona Lecturer in English, 1974-77 PUBLICATIONS 6. Books and monographs: Music, Memory, Resistance: Calypso and the Caribbean Literary Imagination. Eds. Sandra Pouchet Paquet, Patricia Saunders, Stephen Stuempfle. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, 2007. Caribbean Autobiography: Cultural Identity and Self-Representation. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press (Autobiography Series), 2002. The Novels of George Lamming. London: Heinemann, 1982. 7. Juried or refereed journal articles, scholarly reviews, journals edited, etc: Interview. “This is how I know myself”: A Conversation with Sandra Pouchet Paquet by Sheryl Gifford. sx salon 9 (May 1212): 10 pages. “Stitch By Stitch: Sewing up Questions of Cultural Identity: Lorna Goodison’s From Harvey River.” Small Axe: Book Discussion: Lorna Goodison, From Harvey River. -

Introduction

I INTRODUCTION The objective of the thesis has been to explore the rootlessness in the major fictional works of V.S. Naipaul, the-Trinidad-born English author. The emphasis has been on the analysis of his writings, in which he has depicted the images of home, family and association. Inevitably, in this research work on V.S. Naipaul’s fiction, multiculturalism, homelessness (home away from home) and cultural hybridity has been explored. Naipaul has lost his roots no doubt, but he writes for his homeland. He is an expatriate author. He gives vent to his struggle to cope with the loss of tradition and makes efforts to cling to the reassurance of a homeland. Thepresent work captures the nuances of the afore-said reality. A writer of Indian origin writing in English seems to have an object, that is his and her imagination has to be there for his/her mother country. At the core of diaspora literature, the idea of the nation-state is a living reality. The diaspora literature, however, focuses on cultural states that are defined by immigration counters and stamps on one’s passport. The diaspora community in world literature is quite complex. It has shown a great mobility and adaptability as it has often been involved in a double act of migration from India to West Indies and Africa to Europe or America on account of social and political resources. Writers like Salman Rushdie, RohingtonMistry, Bahrain Mukherjee, and V.S. Naipaul write from their own experience of hanging in limbo between two identities: non-Indian and Indian. -

Aj Thesis Corrected.Pages

The Liminal Text: Exploring the Perpetual Process of Becoming with particular reference to Samuel Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners and George Lamming’s The Emigrants & Kitch: A Fictional Biography of The Calypsonian Lord Kitchener Anthony Derek Joseph A Thesis Submitted For The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Comparative Literature Goldsmiths College, University of London August 2016 Joseph 1! I hereby declare that this thesis represents my own research and creative work Anthony Joseph Joseph 2! Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge the assistance of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) in providing financial support to complete this work. I also express my warm and sincere thanks to my supervisors Professors Blake Morrison and Joan Anim-Addo who provided invaluable support and academic guidance throughout this process. I am also grateful to the English and Comparative Literature Department for their logistic support. Thanks to Marjorie Moss and Leonard ‘Young Kitch’ Joseph for sharing their memories. I would also like to thank Valerie Wilmer for her warmth and generosity and the calypso archivist and researcher Dmitri Subotsky, who generously provided discographies, literature, and numerous rare calypso recordings. I am grateful to my wife Louise and to my daughters Meena and Keiko for their love, encouragement and patience. Anthony Joseph London December 16 2015 Joseph 3! Abstract This practice-as-research thesis is in two parts. The first, Kitch, is a fictional biography of Aldwyn Roberts, popularly known as Lord Kitchener. Kitch represents the first biographical study of the Trinidadian calypso icon, whose arrival in Britain onboard The Empire Windrush was famously captured in Pathé footage. -

Earl Lovelace and the Task of •Œrescuing the Futureâ•Š

Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal Volume 4 Article 8 Issue 2 Earl Lovelace: A Special Issue December 2006 The aN tion/A World/A Place to be Human: Earl Lovelace and the Task of “Rescuing the Future” Jennifer Rahim [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium Recommended Citation Rahim, Jennifer (2006) "The aN tion/A World/A Place to be Human: Earl Lovelace and the Task of “Rescuing the Future”," Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium/vol4/iss2/8 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rahim: The Nation/A World/A Place to be Human: Earl Lovelace and the... Earl Lovelace’s fiction and public addresses1 are preoccupied with two interdependent subjects. The first is Europe’s colonization of the New World, which brought diverse peoples together under severe conditions of systematized inequality. The second is the unique cultural shape this ingathering generated in Caribbean societies and the invitation its continued evolution holds out to citizens to create a different future, not only for them, but also for the world. For Lovelace, therefore, the saving irony of the region’s terrible history is precisely this meeting of so many peoples who, consciously or not, have been “all geared to the New World challenge” (Growing in the Dark 226). -

Vol 23 / No. 1 & 2 / April/November 2015

1 Vol 23 / No. 1 & 2 / April/November 2015 Volume 23 Nos. 1 & 2 April/November 2015 Published by the discipline of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Nadia Huggins Anu Lakhan (copy editor) Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] OR Ms. Angela Trotman Department of Language, Linguistics and Literature Faculty of Humanities, UWI Cave Hill Campus P.O. Box 64, Bridgetown, BARBADOS, W.I. e-mail: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTION RATE US$20 per annum (two issues) or US$10 per issue Copyright © 2015 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Lisa Outar Ian Strachan BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. Edited by full time academics and with minimal funding or institutional support, the Journal originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. -

Lucayos 5.5X8.5.Indd

Volume 1 Volume Volume 1 LUCAYOS School of English Studies Spring 2008 The College of The Bahamas P.O. Box N-4912 Nassau, Bahamas 9 789768 170903 LLucayosCoverucayosCover toto pprint.inddrint.indd 1 55/21/08/21/08 111:33:591:33:59 AAMM LUCAYOS 2008 Media Enterprises Ltd Nassau, Bahamas LUCAYOS Volume 1, Spring 2008 EDITORS Marjorie Brooks-Jones Daphne M. Grace Ian G. Strachan EDITORIAL ADVISORS Victor Chang Mark McWatt Jennifer Rahim CORRESPONDENCE AND SUBSCRIPTION REQUESTS All correspondence and subscription requests should be addressed to: Lucayos School of English Studies Th e College of Th e Bahamas P.O. Box N4912 Nassau, Bahamas Telephone: (242) 302-4381/5 Email: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTIONS Individual copies $15.00 (Bahamian or US dollars) Cheque/money order payable to Th e College of Th e Bahamas Copyright ©2008 Th e College of Th e Bahamas ISBN 10: 976-8170-90-5 ISBN 13: 978-976-8170-90-3 EAN: 9789768170903 COVER “Old Man” by John Cox (2002) Layout design by Media Enterprises Ltd, PO Box N-9240, 31 Shirley Park Avenue, Nassau, Bahamas Tel: 242 325 8210 Fax: 242 325 8065 - Contents - Editors v Editorial Advisors vi Editors’ Introduction to Lucayos vii 1 Th e Silent Scream in Selected Texts by West Indian Writers 9 Jean Antoine-Dunne 2 Th e Tourist and the Native: Rereading Myths of Conquest in Lucy and Last Virgin in Paradise 21 Carolyn Cooper 3 Mapping Patriotic Pain: Caribbean novels of D’Aguiar and Danticat 33 Daphne M. Grace 4 Laying the Past to Rest: Revising History by Resisting Death in Fred D’Aguiar’s Feeding the Ghosts -

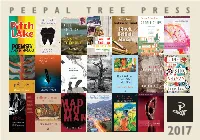

P E E P a L T R E E P R E

P E E P A L T R E E P R E S S 2017 Welcome to our 2017 catalogue! Peepal Tree brings you the very best of international writing from the Caribbean, its diasporas and the UK. Founded in 1985, Peepal Tree has published over 370 books and has grown to become the world’s leading publisher of Caribbean and Black British Writing. Our goal is to publish books that make a difference, and though we always want to achieve the best possible sales, we’re most concerned with whether a book will still be alive and have value in the future. Visit us at www.peepaltreepress.com to discover more. Peepal Tree Press 17 Kings Avenue, Leeds LS6 1QS, United Kingdom +44 (0)1 1 3 2451703 contact @ peepaltreepress.com www.peepaltreepress.com Trade Distribution – see back cover Madwoman SHARA MCCALLUM “These wonderful poems open a world of sensation and memory. But it is a world revealed by language, never just controlled. The voice that guides the action here is openhearted and openminded—a lyric presence that never deserts the subject or the reader. Syntax, craft and cadence add to the gathering music from poem to poem with—to use a beautiful phrase from the book, ‘each note tethering sound to meaning.’” —Eavan Boland Sometimes haunting and elusive, but ultimately transformative, the poems in Shara McCallum’s latest collection Madwoman chart and intertwine three stages of a woman’s life from childhood to adulthood to motherhood. Rich with the 9781845233396 / 80 pages / £8.99 POETRY complexities that join these states of being, the poems wrestle with the idea of JANUARY 2017 being girl, woman and mother all at once. -

Haitians' Labor and Leisure on Cuban Sugar

New West Indian Guide Vol. 85, no. 1-2 (2011), pp. 5-30 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/nwig/index URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101380 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 1382-2373 MATTHEW CASEY HAITIans’ LABOR AND LEISURE ON CUBAN SUGAR PLANTATIONS: ThE LIMITS OF COMPANY CONTROL Alejo Carpentier’s 1927 novel, ¡Écue-Yamba-Ó! (2002:18, 21, 52, 65-66), describes rural Cuba during World War I as a place in which “life is orga- nized according to [sugar’s] will.”1 One effect of sugar production was the “new plague” of “ragged Haitians” or “black mercenaries with straw hats and machetes at their belts.” When not cutting cane, these immigrants seques- tered themselves in their barracones (labor barracks), the “stone construc- tions, long like a hangar, with iron window panes” that were originally built for slaves to inhabit. Haitians and other immigrants were the targets of scorn from Carpentier’s protagonist, Menegildo Cue, an Afro-Cuban individual who drove oxen on the local sugar plantation. He “felt strange among so many blacks with other customs and languages. The Jamaicans were ‘snobby’ and animals! The Haitians were animals and savages!” Cue also complained that Cubans “were without work since the braceros from Haiti accepted incredibly low daily wages!” As Carpentier’s text emphasizes, the arrival of Haitian laborers in eastern Cuba in the first half of the twentieth century was part and parcel of massive rural transformations as a result of the rapid growth of sugar production on the island. -

Teaching Caribbean Poetry COURSE CODE: EDLA3111 DURATION: 39 Hours NO

UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL STUDIES COURSE OUTLINE COURSE TITLE: Teaching Caribbean Poetry COURSE CODE: EDLA3111 DURATION: 39 hours NO. OF CREDITS: 3 LENGTH OF COURSE: ONE SEMESTER PRE-REQUISITES: Any Level 1 poetry course RATIONALE Teachers in the Caribbean and UK face some challenges in the teaching of poetry as indicated in the Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (Ofsted) UK, and Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate (CSEC) reports on achievement in this area. The difficulties have been reflected in teachers teaching rigidly to the tenets of the relevant national curriculum, but often without flair, enthusiasm and confidence; concentrating on students passing exams rather than gaining a rich understanding of, and passion for, poetry; and even avoiding teaching poetry (or aspects of it they find too demanding). Cremin et al in UK (2008, 2009,) noted the considerable insecurity of teachers’ subject knowledge in relation to poetry. One result of this relative lack of expertise is that school students tend to be negative, at worst, or cautious, at best, about poetry. Instead of personal responses to the meaning and musicality of the poem, students tend to focus on limited academic approaches such as ‘hunting the device’ i.e. looking out for figures of speech and thereby losing both the sense of the poem and the pleasures it offers. Conversely, some students treat the poetry experience, as a sort of ‘outpouring’ of pent-up emotions, without understanding of the patterns in language that might trigger such effects- in fact the necessity for analysis, refined and extended by deeper and wider encounters with poetry. -

Including 2016 Titles Visit Us at To

Welcome to our Spring/Summer 2017 catalogue! Including 2016 titles Peepal Tree brings you the very best of international writing from the Caribbean, its diasporas and the UK. Founded in 1985, Peepal Tree has published over 350 books and has grown to become the world’s leading publisher of Caribbean and Black British Writing. Our goal is to publish books that make a difference, and though we always want to achieve the best possible sales, we’re most concerned with whether a book will still be alive and have value in the future. Visit us at www.peepaltreepress.com to discover more. Peepal Tree Press 17 Kings Avenue, Leeds LS6 1QS, United Kingdom +44 (0)1 1 3 2451703 info @ peepaltreepress.com www.peepaltreepress.com 1 Madwoman SHARA MCCALLUM “These wonderful poems open a world of sensation and memory. But it is a world revealed by language, never just controlled. The voice that guides the action here is openhearted and openminded—a lyric presence that never deserts the subject or the reader. Syntax, craft and cadence add to the gathering music from poem to poem with—to use a beautiful phrase from the book, ‘each note tethering sound to meaning.’” —Eavan Boland Sometimes haunting and elusive, but ultimately transformative, the poems in Shara McCallum’s latest collection Madwoman chart and intertwine three stages of a woman’s life from childhood to adulthood to motherhood. Rich with the 9781845233396 / 72 pages / £8.99 POETRY complexities that join these states of being, the poems wrestle with the idea of Print / 23 JAN 2017 being girl, woman and mother all at once. -

Book Reviews -Dennis Walder, Robert D. Hamner, Derek Walcott. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1993

Book Reviews -Dennis Walder, Robert D. Hamner, Derek Walcott. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1993. xvi + 199 pp.''Critical perspectives on Derek Walcott. Washington DC: Three continents, 1993. xvii + 482 pp. -Yannick Tarrieu, Lilyan Kesteloot, Black writers in French: A literary history of Negritude. Translated by Ellen Conroy Kennedy. Washington DC: Howard University Press, 1991. xxxiii + 411 pp. -Renée Larrier, Carole Boyce Davies ,Out of the Kumbla: Caribbean women and literature. Trenton NJ: Africa World Press, 1990. xxiii + 399 pp., Elaine Savory Fido (eds) -Renée Larrier, Evelyn O'Callaghan, Woman version: Theoretical approaches to West Indian fiction by women. London: Macmillan Caribbean, 1993. viii + 126 pp. -Lisa Douglass, Carolyn Cooper, Noises in the blood: Orality, gender and the vulgar' body of Jamaican popular culture. London: Macmillan Caribbean, 1993. ix + 214 pp. -Christine G.T. Ho, Kumar Mahabir, East Indian women of Trinidad This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/07/2021 01:55:37AM via free access BOOK REVIEWS Derek Walcott. ROBERT D. HAMNER. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1993. xvi + 199 pp. (Cloth US$ 22.95) Critical Perspectives on Derek Walcott. ROBERT D. HAMNER (ed.). Wash- ington DC: Three Continents, 1993. xvii + 482 pp. (Paper US$ 20.00) DENNIS WALDER Literature Department Open University, Walton Hall Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, United Kingdom Derek Walcott's achievement as a poet and dramatist is so large that it re- defines the map of contemporary literature. Long before he received the ultimate accolade of the Nobel Prize for Literature, his work demanded recognition beyond the confines of what was conventionally understood as West Indian or Caribbean literature.