Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Psychological Study in James Joyce's Dubliners and VS

International Conference on Shifting Paradigms in Subaltern Literature A Psychological Study in James Joyce’s Dubliners and V. S. Naipaul’s Milguel Street: A Comparative Study Dr.M.Subbiah OPEN ACCESS Director / Professor of English, BSET, Bangalore Volume : 6 James Joyce and [V]idiadhar [S] Urajprasad Naipaul are two great expatriate writers of modern times. Expatriate experience provides Special Issue : 1 creative urges to produce works of art of great power to these writers. A comparison of James Joyce and V.S. Naipaul identifies Month : September striking similarities as well as difference in perspective through the organization of narrative, the perception of individual and collective Year: 2018 Endeavour. James Joyce and V.S. Naipaul are concerned with the lives of ISSN: 2320-2645 mankind. In all their works, they write about the same thing, Joyce write great works such as Dubliners, an early part of great work, Impact Factor: 4.110 and Finnegans Wake, in which he returns to the matter of Dubliners. Similarly, Naipaul has written so many works but in his Miguel Citation: Street, he anticipated the latest autobiographical sketch Magic Seeds Subbiah, M. “A returns to the matter of Miguel Street an autobiographical fiction Psychological Study in about the life of the writer and his society. James Joyce’s Dubliners James Joyce and V.S. Naipaul are, by their own confession, and V.S.Naipaul’s committed to the people they write about. They are committed to the Milguel Street: A emergence of a new society free from external intrusion. Joyce wrote Comparative Study.” many stories defending the artistic integrity of Dubliners. -

LYNNE MACEDO Auteur and Author: a Comparison of the Works of Alfred Hitchcock and VS Naipaul

EnterText 1.3 LYNNE MACEDO Auteur and Author: A Comparison of the Works of Alfred Hitchcock and V. S. Naipaul At first glance, the subjects under scrutiny may appear to have little in common with each other. A great deal has been written separately about the works of both Alfred Hitchcock and V. S. Naipaul, but the objective of this article is to show how numerous parallels can be drawn between many of the recurrent ideas and issues that occur within their respective works. Whilst Naipaul refers to the cinema in many of his novels and short stories, his most sustained usage of the filmic medium is to be found in the 1971 work In a Free State. In this particular book, the films to which Naipaul makes repeated, explicit reference are primarily those of the film director Alfred Hitchcock. Furthermore, a detailed textual analysis shows that similarities exist between the thematic preoccupations that have informed the output of both men throughout much of their lengthy careers. As this article will demonstrate, the decision to contrast the works of these two men has, therefore, been far from arbitrary. Naipaul’s attraction to the world of cinema can be traced back to his childhood in Trinidad, an island where Hollywood films remained the predominant viewing fare throughout most of his formative years.1 The writer’s own comments in the “Trinidad” section of The Middle Passage bear this out: “Nearly all the films shown, apart from those in the first-run cinemas, are American and old. Favourites were shown again and Lynne Macedo: Alfred Hitchcock and V. -

A Study of Place in the Novels of VS Naipaul

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Towards a New Geographical Consciousness: A Study of Place in the Novels of V. S. Naipaul and J. M. Coetzee Thesis submitted by Taraneh Borbor for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy in English literature The University of Sussex September 2010 1 In the Name of God 2 I declare that the work in this thesis was carried out in accordance with the regulations of the University of Sussex. The work is original except where indicated by special reference in the text and no part of the thesis has been submitted for any other degree. The thesis has not been presented to any other university for examination either in the United Kingdom or overseas. Signature: 3 ABSTRACT Focusing on approaches to place in selected novels by J. M. Coetzee and V. S. Naipaul, this thesis explores how postcolonial literature can be read as contributing to the reimagining of decolonised, decentred or multi-centred geographies. I will examine the ways in which selected novels by Naipaul and Coetzee engage with the sense of displacement and marginalization generated by imperial mappings of the colonial space. -

Shuggie Bain : Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2020 Download Free

SHUGGIE BAIN : SHORTLISTED FOR THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 Author: Douglas Stuart Number of Pages: 448 pages Published Date: 15 Apr 2021 Publisher: Pan MacMillan Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781529064414 DOWNLOAD: SHUGGIE BAIN : SHORTLISTED FOR THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 Shuggie Bain : Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2020 PDF Book One page led to another and soon we realised we had created over 100 recipes and written 100 pages of nutrition advice. Have you already achieved professional and personal success but secretly fear that you have accomplished everything that you ever will. Translated from the French by Sir Homer Gordon, Bart. Bubbles in the SkyHave fun and learn to read and write English words the fun way. 56 street maps focussed on town centres showing places of interest, car park locations and one-way streets. These approaches only go so far. Hartsock situates narrative literary journalism within the broader histories of the American tradition of "objective" journalism and the standard novel. Margaret Jane Radin examines attempts to justify the use of boilerplate provisions by claiming either that recipients freely consent to them or that economic efficiency demands them, and she finds these justifications wanting. " -The New York Times Book Review "Empire of Liberty will rightly take its place among the authoritative volumes in this important and influential series. ) Of critical importance to the approach found in these pages is the systematic arranging of characters in an order best suited to memorization. Shuggie Bain : Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2020 Writer About the Publisher Forgotten Books publishes hundreds of thousands of rare and classic books. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

US Regulatory and Tax Considerations for Offshore Funds Mark H

Journal of International Business and Law Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 1 2002 US Regulatory and Tax Considerations for Offshore Funds Mark H. Barth Marco Blanco Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/jibl Recommended Citation Barth, Mark H. and Blanco, Marco (2002) "US Regulatory and Tax Considerations for Offshore Funds," Journal of International Business and Law: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/jibl/vol1/iss1/1 This Legal Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of International Business and Law by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Barth and Blanco: US Regulatory and Tax Considerations for Offshore Funds US Regulatory and Tax Considerations for Offshore Funds Mark H. Barth and Marco Blanco Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle LLP,* New York FirstPublished in THE CAPITAL GUIDE TO OFFSHOREFUNDS 2001, pp. 15-61 (ISI Publications,sponsored by Citco, eds. Sarah Barham and Ian Hallsworth) 2001. Offshore funds' continue to provide an efficient, innovative means of facilitating cross-border connections among investors, investment managers and investment opportunities. They are delivery vehicles for international investment capital, perhaps the most agile of economic factors of production, leaping national boundaries in the search for investment expertise and opportunities. Traditionally, offshore funds have existed in an unregulated state of grace; or disgrace, some would say. It is a commonplace to say that this is changing, both in the domiciles of offshore funds and in the various jurisdictions in which they seek investors, investments or managers. -

Paradox of Freedom in the Novels of V. S. Naipaul

International Jour nal of Applie d Researc h 2020; 6(2): 100-102 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Paradox of freedom in the novels of V. S. Naipaul Impact Factor: 5.2 IJAR 2020; 6(2): 100-102 www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 16-12-2019 Amandeep Accepted: 18-01-2020 Abstract Amandeep In addition to upsetting the cultural ties of the colonized people, colonization also led to their uprooting PGT English, AMSSS Ghaso and displacement. There was a massive transplantation of population between the colonies which Khurd, Jind, Haryana, India separated the colonized from their native lands and forced them to accommodate themselves in alien surroundings. This shift of population between the colonies was a deliberate measure taken to make the colonial societies heterogeneous, as homogeneous ones could have caused a political threat to the colonizers. this mixing up of various peoples created grave problems both at the individual and social levels. The intense alienation and sense of homelessness that such colonized individuals experience maybe ascribed to their displacement in the alien environment. Keywords: Paradox, freedom, novels Introduction Cultural colonization accomplished what military conquest alone could not have achieved for the colonizers. It paved its way into the minds of the colonised and made them complaisant victims. This colonization of the minds maimed the psyche of the colonized in a severe way. It robbed them of all originality and instead, instilled in them a dependency complex. The crippling effect of this complex manifests itself in the post independence period in the inability of the former colonized people to stand independently on their own and in their continuing dependence on the West for ideas and technology. -

Vol.5.Issue 2. 2017 (April-June)

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.5.Issue 2. 2017 http://www.rjelal.com; (April-June) Email:[email protected] ISSN:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE HYBRIDITY AND MIMICRY IN V S NAIPAUL’S NOVELS A HOUSE FOR MR BISWAS, THE ENIGMA OF ARRIVAL & HALF A LIFE SUMAN WADHWA Ph D scholar Email:[email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is an attempt to probe into the cross cultural issues occurred due to Diaspora in the writings of V S Naipaul . It highlights the concept of hybridity , mimicry, nostalgia for a lost home, disillusionment of expatriation, fragmentation of the self, exuberance of immigration, assimilation, cultural translation and negotiation through the selected novels of the writer.It examines the feelings of rootlessness and alienation. The term hybridity has become very popular in postcolonial cultural criticism. Diasporas try their best at first to keep their own identity in their own community. But outside of community, their social identity is lost due to their migration from their homeland to adopted country. His novels deal with problematic intercultural relations and hyphenated identities the female characters in their novels count the benefits of gaining privacy, freedom, egalitarianism against the cost of losing the extended family spirituality tradition and status. Key Words: Rootlessness, Multiculturalism, Hybridity, Post colonialism, Displacement. ©KY PUBLICATIONS This paper maps out the Problems of the House For Mr Biswas(1961),The Enigma Of Arrival Indian expatriates and immigrants and brings in light (1987) & Half a life(2001) . their diasporic experience, feeling of rootlessness Postcolonial writers attempt to show and process of hybridization in the hostlands. -

Women Novelists in Indian English Literature

WOMEN NOVELISTS IN INDIAN ENGLISH LITERATURE DR D. RAJANI DEIVASAHAYAM S. HIMA BINDU Associate Professor in English Assistant Professor in English Ch. S. D. St. Theresa’s Autonomous College Ch. S. D. St. Theresa’s Autonomous for Women College for Women Eluru, W.G. DT. (AP) INDIA Eluru, W.G. DT., (AP) INDIA Woman has been the focal point of the writers of all ages. On one hand, he glorifies and deifies woman, and on the other hand, he crushes her with an iron hand by presenting her in the image of Sita, the epitome of suffering. In the wake of the changes that have taken place in the society in the post-independence period, many novelists emerged on the scene projecting the multi-faceted aspects of woman. The voice of new Indian woman is heard from 1970s with the emergence of Indian English women novelists like Nayantara Sehgal, Anitha Desai, Kamala Markandaya, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, Arundhati Roy, Shashi Deshpande, Gita Mehta, Bharathi Mukherjee, and Jhumpha Lahiri.. These Feminist writers tried to stamp their authority in a male dominated environment as best as it is possible to them. This paper focuses on the way these women writers present the voice of the Indian woman who was hitherto suppressed by the patriarchal authority. Key words: suppression, identity, individuality, resistance, assertion. INTRODUCTION Indian writers have contributed much for the overall development of world literature with their powerful literary expression and immense depth in characterization. In providing global recognition to Indian writing in English, the novel plays a significant role as they portray the multi-faceted problems of Indian life and the reactions of common men and women in the society. -

Chapter-Ii Journey of Women Novelists in India

CHAPTER-II JOURNEY OF WOMEN NOVELISTS IN INDIA 2.1 Preliminaries This chapter deals with the study of „novel‟ as a popular literary genre. It traces the advent of the novel in India which is a product of colonial encounter. Essentially dominated by male writers, women‟s writings in the past were looked down upon as inconsequential. Literary contributions by Indian women writers were undervalued on account of patriarchal assumptions which prioritized the works of male experiences. For many women writers, who are products of strong patriarchal cultures, ability to write and communicate in the language of the colonizers represents power. Since English is the language of British-ruled colonies, literature written in English has often been used to marginalize and thwart female point of view. But in the post-colonial era, however, the ability to use language, read, write, speak and publish has become an enabling tool to question the absence of female authorial representation from the literary canon. Post-colonial studies sparks off questions related to identity, race, gender and ethnicity. Since one of the objectives of the post-colonial discourse is aimed at re- instating the marginalized in the face of the dominant some of the aspects it seeks to address through its fictions are those related to women‟s status in society, gender bias, quest for identity among others. As Rosalind Miles remarks, The task of interpretation of women‟s experience cannot be left to male writers alone, however sympathetic they might be. The female perspective expressed through women‟s writings of all kinds is more than a valuable corrective to an all-male view of the universe.1 Taking this argument into consideration, the present chapter will very briefly study the works of women novelists in India. -

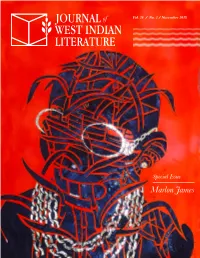

Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018

Vol. 26 / No. 2 / November 2018 Special Issue Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018 Published by the Departments of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Sugar Daddy #2 by Leasho Johnson Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2018 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Lisa Outar (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Kevin Adonis Browne BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. JWIL originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. It reflects the continued commitment of those who followed their lead to provide a forum in the region for the dissemination and discussion of our literary culture. -

THE INDIAN JOURNAL of ENGLISH STUDIES an Annual Journal

ISSN-L 0537-1988 53 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES An Annual Journal VOL.LIII 2016 Editor-in-Chief Dr. Binod Mishra Associate Professor of English, IIT Roorkee The responsibility for facts stated, opinion expressed or conclusions reached and plagiarism, if any, in this Journal is entirely that of the author. The editor/publisher bears no responsibility for them whatsoever. THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA 53 2016 INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Binod Mishra, CONTENTS Department of HSS, IIT Roorkee, Uttarakhand. The Indian Journal of English Studies (IJES), published since 1940, accepts Editorial Binod Mishra VII scholarly papers presented by members at the annual conferences World Literature in English of the Association for English Hari Mohan Prasad 1 Studies of India (AESI). Orders for the Indian and Western Canon copy of the journal for home, college, Charu Sheel Singh 12 departmental/university library may be sent to the Editor-in-Chief, Mahesh Dattani’s Ek Alag Mausam: Dr. Binod Mishra, by sending an Art for Life’s Sake Mukesh Ranjan Verma 23 e-mail on [email protected]. Teachers and research scholars are Encounters in the Human requested to place orders on behalf of Zoo through Albee their institutions for one or more J. S. Jha 33 copies. Orders can be sent to Dr. Binod John Dryden and the Restoration Milieu Mishra, Editor-in-Chief, IJES, 215/3 Vinod Kumar Singh 45 Saraswati Kunj, IIT Roorkee, District- Folklore and Film: Commemorating Haridwar, Uttarakhand-247667, Vijaydan Detha, the Shakespeare India.