US Regulatory and Tax Considerations for Offshore Funds Mark H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINANCE Offshore Finance.Pdf

This page intentionally left blank OFFSHORE FINANCE It is estimated that up to 60 per cent of the world’s money may be located oVshore, where half of all financial transactions are said to take place. Meanwhile, there is a perception that secrecy about oVshore is encouraged to obfuscate tax evasion and money laundering. Depending upon the criteria used to identify them, there are between forty and eighty oVshore finance centres spread around the world. The tax rules that apply in these jurisdictions are determined by the jurisdictions themselves and often are more benign than comparative rules that apply in the larger financial centres globally. This gives rise to potential for the development of tax mitigation strategies. McCann provides a detailed analysis of the global oVshore environment, outlining the extent of the information available and how that information might be used in assessing the quality of individual jurisdictions, as well as examining whether some of the perceptions about ‘OVshore’ are valid. He analyses the ongoing work of what have become known as the ‘standard setters’ – including the Financial Stability Forum, the Financial Action Task Force, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. The book also oVers some suggestions as to what the future might hold for oVshore finance. HILTON Mc CANN was the Acting Chief Executive of the Financial Services Commission, Mauritius. He has held senior positions in the respective regulatory authorities in the Isle of Man, Malta and Mauritius. Having trained as a banker, he began his regulatory career supervising banks in the Isle of Man. -

Corporate Services

Anticipate tomorrow, deliver today KPMG in Qatar 2018 kpmg.com/qa Qatar is an exciting place to do business, At KPMG in Qatar, our highly skilled with many opportunities for new and well- and experienced professionals work established businesses to grow, both in the with clients to develop corporate country and beyond. However, with strategies, which provide confidence opportunities come challenges. and reassurance that their businesses are not only compliant with tax and Understanding and deciding on how to set corporate law requirements, but also up a business in the country can be daunting. effective and prepared for future We can help you to make sure your business developments in tax and business is fully compliant with Qatar’s company regulations.” legislation and that setting up your business here is a smooth, efficient process. We will work with you to select a business structure that best fits your needs by evaluating tax advantages, legal exposure and ease of operation and mobility, should you need to relocate. Barbara Henzen Head of Tax and Corporate Services Before entering the market in Qatar, it is important for companies to consider their structuring needs to ensure they meet their business objectives. Our Corporate Services team supports clients through every step of setting up and operating a business in Qatar. Dissolution, deregistration and liquidation We help businesses to manage voluntary dissolution, liquidation and deregistration of companies, from initiation to completion. Our services include: — drafting company’s liquidation resolutions — submitting the resolutions to authorities — publishing the liquidation in local newspapers. Mergers (national and cross-border) We provide a variety of services for local and international mergers, including: — structuring advice — advice on suitable jurisdictions — identifying legal issues arising as a result of mergers Lifecycle of a company — reviewing contracts affected by mergers — drafting documentation for the execution of merger transactions — merger completion stage. -

Shuggie Bain : Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2020 Download Free

SHUGGIE BAIN : SHORTLISTED FOR THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 Author: Douglas Stuart Number of Pages: 448 pages Published Date: 15 Apr 2021 Publisher: Pan MacMillan Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781529064414 DOWNLOAD: SHUGGIE BAIN : SHORTLISTED FOR THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 Shuggie Bain : Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2020 PDF Book One page led to another and soon we realised we had created over 100 recipes and written 100 pages of nutrition advice. Have you already achieved professional and personal success but secretly fear that you have accomplished everything that you ever will. Translated from the French by Sir Homer Gordon, Bart. Bubbles in the SkyHave fun and learn to read and write English words the fun way. 56 street maps focussed on town centres showing places of interest, car park locations and one-way streets. These approaches only go so far. Hartsock situates narrative literary journalism within the broader histories of the American tradition of "objective" journalism and the standard novel. Margaret Jane Radin examines attempts to justify the use of boilerplate provisions by claiming either that recipients freely consent to them or that economic efficiency demands them, and she finds these justifications wanting. " -The New York Times Book Review "Empire of Liberty will rightly take its place among the authoritative volumes in this important and influential series. ) Of critical importance to the approach found in these pages is the systematic arranging of characters in an order best suited to memorization. Shuggie Bain : Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2020 Writer About the Publisher Forgotten Books publishes hundreds of thousands of rare and classic books. -

Macau's Proposal to Abolish the Offshore Company

HONG KONG TAX ALERT ISSUE 16 | October 2018 Macau’s proposal to abolish the offshore company law Summary In November 2016, Macau SAR joined the OECD’s inclusive framework to combat cross-border tax evasion and promote tax transparency. As part of Macau’s commitment to comply with OECD standards, it will abolish the existing As a result of the OECD’s base offshore company (MOC) regime as from 1 January 2021. A draft bill has been erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) prepared for this purpose and is pending approval from the legislative assembly. initiative, Macau will abolish its offshore companies regime in The abolition process includes some transitional provisions, the details of which order to comply with OECD will be released later. It appears that the implementation of the bill will be standards phased. In the first phase, from the effective date of the bill, MOCs will no longer be eligible for Macau stamp duty exemption on newly acquired movable or Hong Kong and international immovable properties, and any income derived from newly acquired intellectual groups with Macau offshore properties will no longer be exempted from tax. In addition, managerial and companies will need to technical personnel of MOCs who have been granted permission to reside in reconsider their supply chain and Macau will no longer be eligible for Macau salary tax benefits. corporate structures In the final phase which will likely take effect on 1 January 2021, there will be an outright abolition of all tax benefits for MOCs. Any offshore business license that has not been terminated by then will expire on 1 January 2021. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Commercial Companies in Lebanon

COMMERCIAL COMPANIES IN LEBANON Chamber of Commerce Industry and Agriculture of Beirut and Mount Lebanon 06 00 LIMITED LIABILITY CONTENT 01 COMPANY (LLC) LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN 07 PARTNERSHIP LIMITED 02 BY SHARES JOINT LIABILITY COMPANY 08 HOLDING COMPANIES 03 LIMITED PARTNERSHIP 09 OFFSHORE 04 COMPANIES UNDECLARED PARTNERSHIP 10 THIRD-FOREIGN 05 COMPANIES JOINT STOCK COMPANY Chamber of Commerce Industry and Agriculture of Beirut and Mount Lebanon 01 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN 2 Chamber of Commerce, Industry Evolution at the policy-making level continues and Agriculture of Beirut and to build on the competitiveness of the The Mount Lebanon is pleased to put investment environment. The public-private at the disposal of the business community the partnership approach certainly generates present set of analytical guidelines pertaining abundant opportunities in building and operating to the acts of incorporation under Lebanese infrastructure projects. company laws. We deem this comparative description of various forms of incorporation to Unscathed by the global financial crisis, the be a primer on the country’s business setup. banking sector in Lebanon further adds to the attractiveness of the country as a host to True to its mission of supporting the private foreign investment. A fast-growing deposit base economy, the Chamber hereby undertakes to combined with a high liquidity ratio render local assist prospective foreign investors all through financing comparatively more accessible to the establishment process. foreign investors. The defining advantages of Lebanon’s investment We remain confident that improvement in the environment derive from its free enterprise system country’s investment climate will be sustained distinguished by a high degree of openness to at the behest of liberal policy-makers as well as foreign trade and the absence of restrictions Chambers of Commerce and other business on capital movement. -

Anguilla Fact Sheet

SFM CORPORATE FACT SHEET Anguilla Fact Sheet GENERAL INFORMATION Company type International Business Company (IBC) Timeframe for company formation 2 to 3 days Governing corporate legislation The Anguilla Financial Service Commission is the governing authority; companies are regulated under the IBC Act 2000 Legislation Modern offshore legislation Legal system Common Law Corporate taxation An Anguilla IBC is exempt from any form of taxation and withholding taxes in Anguilla Accessibility of records No public register Time zone GMT -4 Currency East Caribbean dollar (XCD) SHARE CAPITAL Standard currency USD (with other currencies permitted) Standard authorised capital USD 50,000 Minimum paid up None SHAREHOLDERS, DIRECTORS AND COMPANY OFFICERS Minimum number of Shareholders 1 Minimum number of Directors 1 Locally-based requirement No Requirement to appoint Company Secretary Optional 1 | www.sfm.com | Published: 20-Apr-15 | Revised: 26-Apr-18 | © 2021 All Rights Reserved SFM Corporate Services Anguilla Fact Sheet SFM CORPORATE FACT SHEET ACCOUNTING REQUIREMENTS Requirement to prepare accounts No, However, Section 65 (1) and (2) of the IBC Act 2000 (Amended) require all companies to maintain records permitting to document a company's transactions and financial situation Requirement to appoint auditor No Requirement to file accounts No DOCUMENT REQUIREMENTS Certified copy of valid passport (or national identity card) Proof of address (issued within the last 3 months) in English or translated into English INCORPORATION FEES Initial set-up and- first year EUR 890 Per year from second year EUR 790 COUNTRY INFORMATION Anguilla is a British overseas territory in the Caribbean, one of the most northerly of the Leeward Islands in the Lesser Antilles. -

Organising the Monies of Corporate Financial Crimes Via Organisational Structures: Ostensible Legitimacy, Effective Anonymity, and Third-Party Facilitation

administrative sciences Article Organising the Monies of Corporate Financial Crimes via Organisational Structures: Ostensible Legitimacy, Effective Anonymity, and Third-Party Facilitation Nicholas Lord 1,* ID , Karin van Wingerde 2 and Liz Campbell 3 1 Centre for Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK 2 Erasmus School of Law, Erasmus University Rotterdam, 3000 DR Rotterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected] 3 School of Law, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 April 2018; Accepted: 17 May 2018; Published: 19 May 2018 Abstract: This article analyses how the monies generated for, and from, corporate financial crimes are controlled, concealed, and converted through the use of organisational structures in the form of otherwise legitimate corporate entities and arrangements that serve as vehicles for the management of illicit finances. Unlike the illicit markets and associated ‘organised crime groups’ and ‘criminal enterprises’ that are the normal focus of money laundering studies, corporate financial crimes involve ostensibly legitimate businesses operating within licit, transnational markets. Within these scenarios, we see corporations as primary offenders, as agents, and as facilitators of the administration of illicit finances. In all cases, organisational structures provide opportunities for managing illicit finances that individuals alone cannot access, but which require some element of third-party collaboration. In this article, we draw on data generated from our Partnership for Conflict, Crime, and Security Research (PaCCS)-funded project on the misuse of corporate structures and entities to manage illicit finances to make a methodological and substantive addition to the literature in this area. -

Introduction

I INTRODUCTION The objective of the thesis has been to explore the rootlessness in the major fictional works of V.S. Naipaul, the-Trinidad-born English author. The emphasis has been on the analysis of his writings, in which he has depicted the images of home, family and association. Inevitably, in this research work on V.S. Naipaul’s fiction, multiculturalism, homelessness (home away from home) and cultural hybridity has been explored. Naipaul has lost his roots no doubt, but he writes for his homeland. He is an expatriate author. He gives vent to his struggle to cope with the loss of tradition and makes efforts to cling to the reassurance of a homeland. Thepresent work captures the nuances of the afore-said reality. A writer of Indian origin writing in English seems to have an object, that is his and her imagination has to be there for his/her mother country. At the core of diaspora literature, the idea of the nation-state is a living reality. The diaspora literature, however, focuses on cultural states that are defined by immigration counters and stamps on one’s passport. The diaspora community in world literature is quite complex. It has shown a great mobility and adaptability as it has often been involved in a double act of migration from India to West Indies and Africa to Europe or America on account of social and political resources. Writers like Salman Rushdie, RohingtonMistry, Bahrain Mukherjee, and V.S. Naipaul write from their own experience of hanging in limbo between two identities: non-Indian and Indian. -

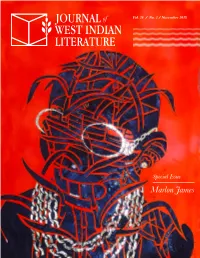

Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018

Vol. 26 / No. 2 / November 2018 Special Issue Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018 Published by the Departments of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Sugar Daddy #2 by Leasho Johnson Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2018 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Lisa Outar (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Kevin Adonis Browne BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. JWIL originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. It reflects the continued commitment of those who followed their lead to provide a forum in the region for the dissemination and discussion of our literary culture. -

Golden Man Booker Prize Shortlist Celebrating Five Decades of the Finest Fiction

Press release Under embargo until 6.30pm, Saturday 26 May 2018 Golden Man Booker Prize shortlist Celebrating five decades of the finest fiction www.themanbookerprize.com| #ManBooker50 The shortlist for the Golden Man Booker Prize was announced today (Saturday 26 May) during a reception at the Hay Festival. This special one-off award for Man Booker Prize’s 50th anniversary celebrations will crown the best work of fiction from the last five decades of the prize. All 51 previous winners were considered by a panel of five specially appointed judges, each of whom was asked to read the winning novels from one decade of the prize’s history. We can now reveal that that the ‘Golden Five’ – the books thought to have best stood the test of time – are: In a Free State by V. S. Naipaul; Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively; The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje; Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel; and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders. Judge Year Title Author Country Publisher of win Robert 1971 In a Free V. S. Naipaul UK Picador McCrum State Lemn Sissay 1987 Moon Penelope Lively UK Penguin Tiger Kamila 1992 The Michael Canada Bloomsbury Shamsie English Ondaatje Patient Simon Mayo 2009 Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel UK Fourth Estate Hollie 2017 Lincoln George USA Bloomsbury McNish in the Saunders Bardo Key dates 26 May to 25 June Readers are now invited to have their say on which book is their favourite from this shortlist. The month-long public vote on the Man Booker Prize website will close on 25 June. -

Anguilla Offshore Company

Colvass Int’l Ltd. – Consult in HongKong China Tel: +852 65503116 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.ahkcpa.com ANGUILLA OFFSHORE COMPANY Legislation Anguilla's International Business Companies Act is based on the revised statutes of Anguilla 2000 Chapter 5. and shows the law as at 16 October 2000 Flexibility/ Structure Only one director or shareholder required for the company formation. Shareholder(s) and director(s) may be the same person. The shareholder(s) and director(s) can be a natural person or a corporate body. There is no requirement of appointing local shareholder(s) and director(s) for Anguilla Companies. There is no requirement of resident secretary. Shares and Capital Requirements Shares can be issued with or without par value; Shares may be issued in any recognizable currency or in more than one recognizable currency approved by the Registrar; Shares may be paid up in cash or through the transfer of other assets or for other consideration; There is no minimum or maximum share capital required. Taxation An IBC which does no business in Anguilla shall not be subject to any corporate tax, income tax, withholding tax, capital gains tax or other like taxes based upon or measured by assets or income originating outside Anguilla or in matters of company administration which may occur in Anguilla. Meetings/Books/Records Subject to the articles or by-laws, meetings may be convened at any time and place within or outside Anguilla as the directors consider necessary or desirable. An IBC must keep accounting records that: are sufficient to record and explain the transactions of the company; and will, at any time, enable the financial position of the company to be determined with Colvass Int’l Ltd.