Earl Lovelace and the Task of •Œrescuing the Futureâ•Š

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol 25 / No. 2 / November 2017 Volume 24 Number 2 November 2017

1 Vol 25 / No. 2 / November 2017 Volume 24 Number 2 November 2017 Published by the discipline of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Self-portrait with projection, October 2017, img_9723 by Rodell Warner Anu Lakhan (copy editor) Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] OR Ms. Angela Trotman Department of Language, Linguistics and Literature Faculty of Humanities, UWI Cave Hill Campus P.O. Box 64, Bridgetown, BARBADOS, W.I. e-mail: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTION RATE US$20 per annum (two issues) or US$10 per issue Copyright © 2017 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Lisa Outar Ian Strachan BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. Edited by full time academics and with minimal funding or institutional support, the Journal originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. -

Conference Schedule

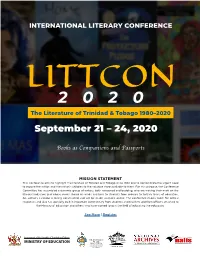

INTERNATIONAL LITERARY CONFERENCE LITTCON2020 The Literature of Trinidad & Tobago 1980–2020 September 21 – 24, 2020 Books as Companions and Passports MISSION STATEMENT This Conference aims to highlight the literature of Trinidad and Tobago since 1980 and to demonstrate the urgent need to expose the nation and the nation’s children to the valuable store available to them. For this purpose, the Conference Committee has assembled a dynamic group of writers, both renowned and budding, who are making their mark on the literary landscape and whose works should be made available to students from primary to tertiary levels of education. An author’s calendar is being constructed and will be made available online. The conference makes room for critical responses and also has specially built in important commentary from students and teachers and from officers attached to the Ministry of Education and others who have worked long in the field of educating the educators. See More | Register THE UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES ST. AUGUSTINE CAMPUS TRINIDAD & TOBAGO WEST INDIES International Literary Conference CALENDAR OF EVENTS: MONDAY 21ST SEPTEMBER, 2020 INTRODUCTION TO THE LITERARY LANDSCAPE OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Day Chair: Dr. J. Vijay Maharaj 8:00am - 8:45 am OPENING THE FRONTIERS Moderator: Dr. J. Vijay Maharaj Welcome, HOD DLCCS: Professor Paula Morgan Greetings by the Principal UWI STA: The Humanities in the 21st Century- Professor Brian Copeland Remarks from the Chairman, Friends of Mr Biswas The Conference: Structure and Purpose – Professor Kenneth Ramchand Feature Address by the Minister of Education: Dr the Honourable Nyan Gadsby-Dolly 8:45am – 9:45am THE HEART OF THE MATTER Moderator: Professor Kenneth Ramchand Presentation of the Annotated Bibliography: Ms. -

University of Miami Coral Gables, FL 33124-4632

Sandra Pouchet Paquet, Ph.D. Professor Emerita, Department of English, University of Miami Coral Gables, FL 33124-4632 Email [email protected] Curriculum Vitae Standard Format 1. Date: July 2013 PERSONAL 2. Name: Sandra Pouchet Paquet HIGHER EDUCATION 3. Institutional (institution; degree; date conferred): University of Connecticut, Storrs; Ph.D. in English; 1976 University of Connecticut, Storrs; M.A. in English; 1971 Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart, Purchase; B.A. (Honors) in English, 1967 4. Certification, licensure (description; board or agency; dates): Spanish 3-Day Mini-Mersion Program, May 18-20, 2007. EXPERIENCE 5. Academic (institutions; rank/status; dates): University of Miami, Professor; 2002-2010 University of Miami; Associate Professor; 1992-2002 University of Miami; Director, Caribbean Writers Summer Institute, 1992-1997 University of Pennsylvania; Assistant Professor; 1985-1992 University of Hartford; Assistant Professor; 1977-85 Director of Black Studies, 1977-79 University of the West Indies, Mona Lecturer in English, 1974-77 PUBLICATIONS 6. Books and monographs: Music, Memory, Resistance: Calypso and the Caribbean Literary Imagination. Eds. Sandra Pouchet Paquet, Patricia Saunders, Stephen Stuempfle. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, 2007. Caribbean Autobiography: Cultural Identity and Self-Representation. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press (Autobiography Series), 2002. The Novels of George Lamming. London: Heinemann, 1982. 7. Juried or refereed journal articles, scholarly reviews, journals edited, etc: Interview. “This is how I know myself”: A Conversation with Sandra Pouchet Paquet by Sheryl Gifford. sx salon 9 (May 1212): 10 pages. “Stitch By Stitch: Sewing up Questions of Cultural Identity: Lorna Goodison’s From Harvey River.” Small Axe: Book Discussion: Lorna Goodison, From Harvey River. -

MW Bocasjudge'stalk Link

1 Bocas Judge’s talk To be given May 4 2019 Marina Warner April 27 2019 The Bocas de Dragon the Mouths of the Dragon, which give this marvellous festival its name evoke for me the primary material of stories, songs, poems in the imagination of things which isn’t available to our physical senses – the beings and creatures – like mermaids, like dragons – which every culture has created and questioned and enjoyed – thrilled to and wondered at. But the word Bocas also calls to our minds the organ through which all the things made by human voices rise from the inner landscapes of our being - by which we survive, breathe, eat, and kiss. Boca in Latin would be os, which also means bone- as Derek Walcott remembers and plays on as he anatomises the word O-mer-os in his poem of that name. Perhaps the double meaning crystallises how, in so many myths and tales, musical instruments - flutes and pipes and lyres - originate from a bone, pierced or strung to play. Nola Hopkinson in the story she read for the Daughters of Africa launch imagined casting a spell with a pipe made from the bone of a black cat. When a bone-mouth begins to give voice – it often tells a story of where it came from and whose body it once belonged to: in a Scottish ballad, to a sister murdered by a sister, her rival for a boy. Bone-mouths speak of knowledge and experience, suffering and love, as do all the writers taking part in this festival and on this splendid short list. -

A Literary Revolutionary 50 for 50 Man Or Machine?

Our Fragile Waters Twenty MSc students in coastal engineering recently went to Grenada on a field trip that yielded much in terms of work, study and relaxation. At the end of the week, there was a visit to the Underwater Sculpture Park, Grenada, and one of the students, Christopher Clarke, found himself in bubbles of euphoria. (See story on Page 8) PHOTO: JENNALEE RAMNARINE CAMPUS – 4 HEALTH – 11 AGRICULTURE – 14 LITERATURE – 15 50 for 50 Man or Machine? The Book of the Earth A Literary Revolutionary Alumni Awards New Teaching Tool for Nurses Soils of the Caribbean Professor Chaman Lal SUNDAY 24TH APRIL, 2011 – UWI TODAY 3 CAMPUS NEWS FROM THE PRINcipal We Found 50 Ways Celebrating Our Distinguished Alumni It has always been a source of personal pride to reflect on the range and caliber of the graduates of the St. Augustine Campus of The UWI. Where ever I venture, whether it be into the various communities and establishments locally, regionally or internationally, I am impressed by the many accomplishments of our graduates and what good work they are doing. I have often publicly said that this region is really in the hands of UWI graduates, because in significant numbers, they are the ones charting its course, whether it is as prime ministers, politicians, first-rate professionals in so many fields, academics, entrepreneurs or artistes.I recently saw some of our accomplished graduates in Toronto as well, where many were celebrated at our fund-raising Gala. Naturally, I was in full support of the initiative taken by the St. -

Calypso Overseas and the Sound of Belonging in Selected Narratives of Migration Jennifer Rahim [email protected]

Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal Volume 3 Issue 2 Calypso and the Caribbean Literary Article 12 Imagination: A Special Issue December 2005 (Not) Knowing the Difference: Calypso Overseas and the Sound of Belonging in Selected Narratives of Migration Jennifer Rahim [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium Recommended Citation Rahim, Jennifer (2005) "(Not) Knowing the Difference: Calypso Overseas and the Sound of Belonging in Selected Narratives of Migration," Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2 , Article 12. Available at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium/vol3/iss2/12 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rahim: (Not) Knowing the Difference: Calypso Overseas and the Sound... Culture is an embodied phenomenon. This implies that one’s cultural location is not fixed to any one geographical space. Cultures, in other words, are not inherently provincial by nature. They move and evolve with the bodies that create and live them. The Caribbean civilization understands the logic of traveling cultures given that the dual forces of rooted-ness and itinerancy shape its diasporic ethos. Travel is how we “do” culture. Indeed, the Caribbean’s literary tradition is marked by a preoccupation with identity constructs that display allegiances to particular island locations and nationalisms, on the one hand, and transnational sensibilities that are regional and metropolitan on the other. This paper is interested in the function of the calypso as a sign of cultural identity and belonging in selected narratives that focus on the experiences of West Indian immigrants to the metropolitan centers of England and the United States. -

Universite Du Benin

UNIVERSITE DU BENIN FACULTE DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUl\JIAINES DEPARTEME~T D'ANGLAIS Lomé-Togo LABORATOIRE DE RECHERCHES EN LITTERATURES DE L'AFRIQUE NOIRE ET DE LA DIASPORA (LABO-LAND) Thèse pour le Doctorat (NR) Option: Littérature Américaine Présentée et soutenue publiquement par: KodjoAFAGLA Sous la direction de : Monsieur le Professeur Komla Messan NUBUKPO Directeur Scientifique du LABO-LAi'l'D - 1999 - To THE MEMORY OF : ** MY SELOVED DAUGHTER DANIELLA-FLORA ; ** MY FATHER, DANIEL KOFFI AFAGLA, WHO SET ME ON THE RIGHT PATH SEFORE HIS PRECOCIOUS DEATH; ** MY GRANDMOTHERS : NORI ASLA ESOUNOUGNA DOTSE AND MAMAN DOVOUNO AFAYOME; ** MY COUSIN, DESIRE EYRAM YAOVI DOTSE, WHO COULD NOT SEE THE COMPLETION OF THIS WORK. vi TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGES HEART-FELT THANKS ................................................................... iv-v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS VI-VIII REFERENCES ......... ......... ............ ................. .... ....... .......... ........... ... IX ABBREVIATIONS ....... ......... ............ ............ ... ....... ................. .......... X CHAPTER ONE: GENERAL INTRODUCTION ............................... 1 CHAPTER TWO : THE COLONIAL QUESTION IN GEORGE LAMMING'S NATIVES OF MY PERSON AND IN THE CASTLE OF MY SKIN ................................................. 18 II. 1. LAMMING'S QUARREL WITH HISTORY : THE DRIVING FORCES OF COLONIALISM ................................................................... 23 II. 2. SOME MYTHS OF COLONIALISM ........................................................... 48 II. 3. THE COLONIAL -

Matura Days - a Memoir for Earl Lawrence Scott [email protected]

Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal Volume 4 Article 10 Issue 2 Earl Lovelace: A Special Issue December 2006 Matura Days - A Memoir For Earl Lawrence Scott [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium Recommended Citation Scott, Lawrence (2006) "Matura Days - A Memoir For Earl," Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 10. Available at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium/vol4/iss2/10 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scott: Matura Days - A Memoir For Earl It was at the end of 1977, or just at the beginning of 1978 that Jenny, my wife (Jenny Green/Jenny Scott) and I met Earl for the first time. It was after a reading of Leroy Clarke’s poetry performed by The Trinidad Theatre Workshop in the Anglican Cathedral in Port-of-Spain. Jenny and I were taken there by Roy Achong, the journalist and photographer, and Phyllis Holder, then the librarian at Holy Name Convent, recently back from London, on whose verandah overlooking Lapeyrouse Cemetery, we used to lime. After this event, at which I remember Eunice Alleyne and Errol Jones reading from the pulpit of the cathedral from Leroy Clarke’s “Douens,” as I remember it, we were introduced in the churchyard to Earl Lovelace, the novelist, Jean Lovelace, his wife, Raoul Pantin, the journalist, and Wilbert Holder, the actor. -

Aj Thesis Corrected.Pages

The Liminal Text: Exploring the Perpetual Process of Becoming with particular reference to Samuel Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners and George Lamming’s The Emigrants & Kitch: A Fictional Biography of The Calypsonian Lord Kitchener Anthony Derek Joseph A Thesis Submitted For The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Comparative Literature Goldsmiths College, University of London August 2016 Joseph 1! I hereby declare that this thesis represents my own research and creative work Anthony Joseph Joseph 2! Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge the assistance of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) in providing financial support to complete this work. I also express my warm and sincere thanks to my supervisors Professors Blake Morrison and Joan Anim-Addo who provided invaluable support and academic guidance throughout this process. I am also grateful to the English and Comparative Literature Department for their logistic support. Thanks to Marjorie Moss and Leonard ‘Young Kitch’ Joseph for sharing their memories. I would also like to thank Valerie Wilmer for her warmth and generosity and the calypso archivist and researcher Dmitri Subotsky, who generously provided discographies, literature, and numerous rare calypso recordings. I am grateful to my wife Louise and to my daughters Meena and Keiko for their love, encouragement and patience. Anthony Joseph London December 16 2015 Joseph 3! Abstract This practice-as-research thesis is in two parts. The first, Kitch, is a fictional biography of Aldwyn Roberts, popularly known as Lord Kitchener. Kitch represents the first biographical study of the Trinidadian calypso icon, whose arrival in Britain onboard The Empire Windrush was famously captured in Pathé footage. -

IDENTITY and HOME in THREE CARIBBEAN AUTHORS By

IDENTITY AND HOME IN THREE CARIBBEAN AUTHORS By HARBHAJAN S. HIRA Bachelor of Science Guru Nanak Dev University Amritsar, Punjab (India) 1974 Master of Arts in English Hamburg University Hamburg, Germany 1987 Master of Arts in English California State University, Stanislaus Turlock, California 2001 Master of Arts in Education California State University, Dominguez Hills Carson, California 2007 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 2020 IDENTITY AND HOME IN THREE CARIBBEAN AUTHORS Dissertation Approved: Dr. Timothy Murphy Dissertation Adviser Dr. Katherine Hallemeier Dr. Martin Wallen Dr. Alyson Greiner ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Several persons have helped making this project successful. My thanks go to Dr. Katherine Hallemeier, who provided feedback with an unprecedented speed in the final weeks of writing. Thanks are due to Professor Emeritus Martin Wallen as well. In spite of his retirement in 2019, Dr. Wallen kindly agreed to stay on the committee and help me get across the finish line. I also enormously benefited from his course on species, race, and surveillance, where I first discussed theorists such as Du Bois and Fanon. I want to thank Dr. Alyson Greiner of Geography too, who provided all the support that can be expected of an outside committee member. A big THANK YOU goes to Dr. Timothy Murphy, however. As my advisor and chair of the committee, he has been instrumental in securing the success of the project. He meticulously read and commented on every single chapter over the past year and a half. -

Henry Swanzy, the BBC, and the Development of Caribbean Literature

"This is London calling the West Indies:" Henry Swanzy, the BBC, and the development of Caribbean literature Glyne Griffith (Do note quote or paraphrase without requisite citation) Introduction Glyne Griffith (Do not quote or paraphrase without requisite citation) Let us begin near the end, that is to say the end of the BBC Caribbean Voices radio program. The end would eventually come in April, 1958, but there is much to be told and much to be written before we arrive at an ending. The year is 1953 and Henry Swanzy, the editor of the BBC Caribbean Voices literary radio program sends a letter dated November 271h from his Oxford Street office in London to his submissions agent, Gladys Lindo in Jamaica. The letter seeks Mrs. Lindo's advice on the appropriateness of editorial comments which Swanzy intends to make during the next scheduled summary of the previous six months of Caribbean Voices broadcasts to the Caribbean. The following extract indicates some of the concerns which Swanzy conveys to Mrs. Lindo: . ..On wider details, I am thinking of referring in the next summary to the death of Seepersad Naipaul, and to the illness of Sam Selvon, and the failure to send [Derek] Walcott to Europe. The last two would be critical remarks, and perhaps you think they would not be suitable in a thing like a summary. It does seem to me that the powers- that-be ought to be made aware of the value of literary work, from the prestige point of view, and the neglect of West Indian writers is really shocking. -

Jamaica's Difficult Subjects

JAMAICA’S DIFFICULT SUBJECTS JAMAICA’S DIFFICULT SUBJECTS NEGOTIATING SOVEREIGNTY IN ANGLopHONE CARIBBEAN LITERATURE AND CRITICISM SHERI-MARIE HARRISON THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS • CoLUMBUS Copyright © 2014 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harrison, Sheri-Marie, 1979– author. Jamaica’s Difficult Subjects : Negotiating Sovereignty in Anglophone Caribbean Literature and Criticism / Sheri-Marie Harrison. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13 : 978-0-8142-1263-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Jamaican literature—History and criticism. 2. Sovereignty in literature. 3. Postcolonialism in literature. 4. Caribbean literature (English)—History and criticism. 5. Motion pictures—Carib- bean Area. I. Title. PR9265.05H37 2014 820.9'97292—dc23 2014013473 Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For my parents, Audley C. Harrison and Esmin Harrison CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION • T he Politics of Sovereignty in Postcolonial West Indian Literary Discourse 1 CHAPTER 1 • “Who worked this evil, brought this distance between us?” Sex and Sovereignty in Sylvia Wynter’s The Hills of Hebron 33 CHAPTER 2 • “What you say, Elsa?” Postcolonial Sovereignty and Gendered Self-Actualization 69 CHAPTER 3 • “ No, my girl, try Bertha”: Race, Gender, Nation, and Criticism in Wide Sargasso Sea and Lionheart Gal 102 CHAPTER 4 • B eyond Inclusion, Beyond Nation: Queering Twenty-First-Century Caribbean Literature 142 Bibliography 181 Index 189 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is a passage in scripture about God’s care for Elijah that resonated with me throughout the process of writing and publishing this book.