The Post-Colonial Christ Paradox: Literary Transfigurations of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WOLE SOYINKA's OGUN ABIBIMAN by Tanure Ojaide

WOLE SOYINKA'S OGUN ABIBIMAN By Tanure Ojaide Thomas Mofolo's Chaka seems to have set a literary trail in Africa, and Shaka has been the subject of many plays and poems. Shaka, the Zulu king, "is seen primarily as a romantic figure in Francophone Africa, as a military figure in Southern Africa. ul Moreover, "the extensive Shaka literature in Africa illustrates the desire of African writers to seek in Africa's past a source that will be relevant to contemporary realities "2 Shaka was a great military leader who restored dignity to his people, the sort of leadership needed in the liberation struggle in Southern Africa. Chaka is political, and "can be considered an extended praise song singing the deeds of this heroic Zulu leader; it can be regarded as an African epic cele brating the founding of an empire. u3 It is ironic that Wole Soyinka' s Ogun Abibi.man appeared the same year, 1976, that Donald Burness published his book on Shaka in African literature, writing that "Although Shaka is alluded to, for instance, in Soyinka's A Dance of the Forest~ the Zulu king appears very seldom in Nigerian literature. " Soyinka's Ogun Abibiman relies on Mofolo's Chaka and its military tradition together with the 0gun myth in the exhorta tion of black people fighting for freedom and human rights in Southern Africa. Ogun is a war-god, and the bringing together of Ogun and Shaka is necessary to fuse the best in Africa's military experience. Though the two have records of wanton killings at one time in their military careers, they, neverthe less, are mythically and historically, perhaps, the greatest warlords in Africa. -

Joerg Rieger

Joerg Rieger Cal Turner Chancellor’s Chair of Wesleyan Studies Distinguished Professor of Theology Vanderbilt Divinity School Affiliate Faculty Turner Family Center for Social Ventures, Owen Graduate School of Management Joerg Rieger is the Cal Turner Chancellor’s Chair of Wesleyan Studies and Distinguished Professor of Theology. Previously he was the Wendland-Cook Endowed Professor of Constructive Theology at Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University. He received an M.Div. from the Theologische Hochschule Reutlingen, Germany, a Th.M. from Duke Divinity School, and a Ph.D. in religion and ethics from Duke University. For more than two decades he has worked to bring together theology and the struggles for justice and liberation that mark our age. His work addresses the relation of theology and public life, reflecting on the misuse of power in religion, politics, and economics. His main interest is in developments and movements that bring about change and in the positive contributions of religion and theology. His constructive work in theology draws on a wide range of historical and contemporary traditions, with a concern for manifestations of the divine in the pressures of everyday life. Author and editor of more than 20 books and over 125 academic articles, his books include Unified We are a Force: How Faith and Labor Can Overcome America’s Inequalities (with Rosemarie Henkel-Rieger, 2016), Faith on the Road: A Short Theology of Travel and Justice (2015), Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude (with Kwok Pui-lan, 2012), Grace under Pressure: Negotiating the Heart of the Methodist Traditions (2011), Globalization and Theology (2010), No Rising Tide: Theology, Economics, and the Future (2009), Christ and Empire: From Paul to Postcolonial Times(2007), and God and the Excluded: Visions and Blindspots in Contemporary Theology (2001). -

Ángel Jazak Gallardo

Ángel Jazak Gallardo CURRICULUM VITAE Associate Director SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY Intern Program Perkins School of Theology [email protected] 5915 Bishop Boulevard Office (214) 768-2216 Dallas, Texas 75275 EDUCATION Southern Methodist University, Graduate Program in Religious Studies | Dallas, TX • Ph.D. in Religion and Culture (high pass – May 2018) · Dissertation title: “Mapping the Nature of Empire: The Legacy of Theological Geography in the Early Iberian Atlantic” Chair – Joerg Rieger, Distinguished Professor of Theology, Graduate Department of Religion and Divinity School, Vanderbilt University · Comprehensive exams Area I – Modern Study of Religion (with honors) Area II – Contemporary Theories and Critiques of Religion and Culture Area III – Christianity and Mesoamerican Religions in the New World Area IV – Historical Approaches to Colonial Spanish America · Language exams – Latin, Spanish; additional languages – Portuguese, Greek (koinonia) Duke University, Divinity School | Durham, NC • Master of Divinity (May 2009) Eastern University | St. David’s, PA • Bachelor of Arts in Theological Studies (May 2006) FELLOWSHIPS & AWARDS • Research Cluster Grant: On Decolonial Options and the Writing of Latin American History, Dedman College Interdisciplinary Institute (2017-2018) • Doctoral Fellow, Center for the Study of Latino/a Christianity and Religions (2012-2018) • Dissertation Fellowship, Louisville Institute (2016-2017) • Doctoral Fellowship, Forum for Theological Exploration (2016-2017) • Dissertation Fellowship, Hispanic Theological -

Ted Hughes in Context Edited by Terry Gifford Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42555-1 — Ted Hughes in Context Edited by Terry Gifford Frontmatter More Information TEDHUGHESINCONTEXT Ted Hughes wrote in a wide range of modes which were informed by an even wider range of contexts to which his lifetime’s reading, interests and experience gave him access. The achievement of Ted Hughes as one of the major poets of the twentieth century is com- plemented by his growing reputation as a writer of letters, plays, literary criticism and translations. In addition, Hughes made impor- tant contributions to education, literary history, emergent environ- mentalism and debates about life writing. Ted Hughes in Context brings together thirty-two contributors who inform new readings of the works and conceptualise Hughes’s work within long-standing critical traditions while acknowledging a new awareness of his future importance. This collection offers consideration not only of the most important aspects of Hughes’s work but also of the most neglected. terry gifford is Visiting Research Fellow at Bath Spa University’s Research Centre for Environmental Humanities. He is also chair of The Ted Hughes Society and is editor of The Cambridge Companion to Ted Hughes (Cambridge University Press, 2011). © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42555-1 — Ted Hughes in Context Edited by Terry Gifford Frontmatter More Information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42555-1 — Ted -

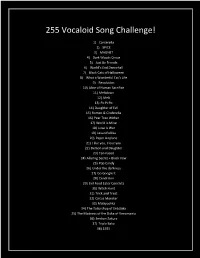

255 Vocaloid Song Challenge!

255 Vocaloid Song Challenge! 1) Canterella 2) SPICE 3) MAGNET 4) Dark Woods Circus 5) Just Be Friends 6) World’s End Dancehall 7) Black Cats of Halloween 8) What a Wonderful Cat’s Life 9) Revolution 10) Alice of Human Sacrifice 11) Meltdown 12) Melt 13) Po Pi Po 14) Daughter of Evil 15) Romeo & Cinderella 16) Pear Tree Wither 17) World is Mine 18) Love is War 19) Levan Polkka 20) Paper Airplane 21) I like you, I love you 22) Demon and Daughter 23) Ten-Faced 24) Alluring Secret + Black Vow 25) Pop Candy 26) Under the darkness 27) Go Google It 28) Cendrillon 29) Evil Food Eater Conchita 30) Witch Hunt 31) Trick and Treat 32) Circus Monster 33) Matryoshka 34) The Tailorshop of Enbizaka 35) The Madness of the Duke of Venomania 36) Senbon Zakura 37) Triple Baka 38) 1925 39) Alice in Musicland 40) Imitation Black 41) Rolling Girl 42) VOiCE 43) Unhappy Refrain 44) Saihate 45) Black Rock Shooter 46) Gift from the Princess who brought Sleep 47) Judgment of Corruption 48) The Last Revolver 49) Last Night, Last Night 50) KOKORO 51) Servant of Evil 52) Synchrocity 53) Honey 54) Dancing Samurai 55) ACUTE 56) Butterfly on your Right Shoulder 57) Gekokujou 58) Bad Apple 59) Princess Mononoke 60) Snow White Medium 61) Snow Bunny 62) Sad Song 63) Nostalgia 64) Time With You 65) Advent Devil 66) Blue Lotus 67) Halloween Girl 68) Marionette 69) MONSTER 70) My Master 71) Rainbow Girl 72) Sumner’s Snow, Winter’s Flower 73) Sweet’s Beast 74) Uninstall 75) When she found out I was an Otaku 76) Winter Cherry Blossom 77) Yume Miru Kotori 78) Beautiful Dreamer -

Wolverine & the X-Men: Tommorow Never Leaves Volume 1 Free

FREE WOLVERINE & THE X-MEN: TOMMOROW NEVER LEAVES VOLUME 1 PDF Jason LaTour,Mahmud A. Asrar | 144 pages | 18 Nov 2014 | Marvel Comics | 9780785189923 | English | New York, United States 9 Best X-Men images | x men, jim lee art, marvel comics covers Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge Wolverine & the X-Men: Tommorow Never Leaves Volume 1. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Mahmud Asrar Illustrator. Welcome to the Jean Grey School of Higher Learning, where Wolverine, Storm, and a star-studded faculty educate the next generation of mutants! But with their own lives steeped in deadly enemies and personal crises, how can the X-Men guide and educate - let alone defend - the school? And what mysterious organization waits in the shadows to destroy Wolverine's mutant sanctua Welcome to the Jean Grey School of Higher Learning, where Wolverine, Storm, and a star-studded faculty educate the next generation of Wolverine & the X-Men: Tommorow Never Leaves Volume 1 And what mysterious organization waits in the shadows to destroy Wolverine's mutant sanctuary? The mysterious Phoenix Corporati on wants Quentin Quire, but why? And only Evan can save Fantomex from certain death - but dare he? Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published November 18th by Marvel first published November 1st More Details Original Title. Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. -

The Myth of the Saving Power of Education: a Practical Theology Approach

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2016 The Myth of the Saving Power of Education: A Practical Theology Approach Hannah Kristine Adams Ingram University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Practical Theology Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Ingram, Hannah Kristine Adams, "The Myth of the Saving Power of Education: A Practical Theology Approach" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1229. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1229 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. THE MYTH OF THE SAVING POWER OF EDUCATION: A PRACTICAL THEOLOGY APPROACH __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the University of Denver and the Iliff School of Theology Joint PhD Program University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Hannah Adams Ingram November 2016 Advisor: Katherine Turpin ©Copyright by Hannah Adams Ingram 2016 All Rights Reserved Author: Hannah Adams Ingram Title: THE MYTH OF THE SAVING POWER OF EDUCATION: A PRACTICAL THEOLOGY APPROACH Advisor: Katherine Turpin Degree Date: November 2016 Abstract U.S. political discourse about education posits a salvific function for success in formal schooling, specifically the ability to “save” marginalized groups from poverty by lifting them into middle- class success. -

Universite Du Benin

UNIVERSITE DU BENIN FACULTE DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUl\JIAINES DEPARTEME~T D'ANGLAIS Lomé-Togo LABORATOIRE DE RECHERCHES EN LITTERATURES DE L'AFRIQUE NOIRE ET DE LA DIASPORA (LABO-LAND) Thèse pour le Doctorat (NR) Option: Littérature Américaine Présentée et soutenue publiquement par: KodjoAFAGLA Sous la direction de : Monsieur le Professeur Komla Messan NUBUKPO Directeur Scientifique du LABO-LAi'l'D - 1999 - To THE MEMORY OF : ** MY SELOVED DAUGHTER DANIELLA-FLORA ; ** MY FATHER, DANIEL KOFFI AFAGLA, WHO SET ME ON THE RIGHT PATH SEFORE HIS PRECOCIOUS DEATH; ** MY GRANDMOTHERS : NORI ASLA ESOUNOUGNA DOTSE AND MAMAN DOVOUNO AFAYOME; ** MY COUSIN, DESIRE EYRAM YAOVI DOTSE, WHO COULD NOT SEE THE COMPLETION OF THIS WORK. vi TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGES HEART-FELT THANKS ................................................................... iv-v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS VI-VIII REFERENCES ......... ......... ............ ................. .... ....... .......... ........... ... IX ABBREVIATIONS ....... ......... ............ ............ ... ....... ................. .......... X CHAPTER ONE: GENERAL INTRODUCTION ............................... 1 CHAPTER TWO : THE COLONIAL QUESTION IN GEORGE LAMMING'S NATIVES OF MY PERSON AND IN THE CASTLE OF MY SKIN ................................................. 18 II. 1. LAMMING'S QUARREL WITH HISTORY : THE DRIVING FORCES OF COLONIALISM ................................................................... 23 II. 2. SOME MYTHS OF COLONIALISM ........................................................... 48 II. 3. THE COLONIAL -

Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S

Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S. Davis and Michael Nacht, editors Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory February 2018 Disclaimer: This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, nor any of their employees makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. LLNL-BOOK-746803 Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue: Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S. Davis and Michael Nacht, editors Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory February -

AP Poetry Prompts with the Poems

MsEffie’s List of Poetry Essay Prompts for Advanced Placement® English Literature Exams, 1970-2019* *Advanced Placement® is a trademark registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse, this website. Each poem is included in the following prompts, printed on separate pages for better use in the classroom. None of the prompts are original to me, but are Advanced Placement® English Literature and Composition Exam prompts. This is my best effort to comply with College Board’s use requirements. 1970 Poem: “Elegy for Jane” (Theodore Roethke) Prompt: Write an essay in which you describe the speaker’s attitude toward his former student, Jane. Elegy for Jane by Theodore Roethke I remember the neckcurls, limp and damp as tendrils; And her quick look, a sidelong pickerel smile; And how, once startled into talk, the light syllables leaped for her, And she balanced in the delight of her thought, 5 A wren, happy, tail into the wind, Her song trembling the twigs and small branches. The shade sang with her; The leaves, their whispers turned to kissing, And the mould sang in the bleached valleys under the rose. 10 Oh, when she was sad, she cast herself down into such a pure depth, Even a father could not find her: Scraping her cheek against straw, Stirring the clearest water. My sparrow, you are not here, 15 Waiting like a fern, making a spiney shadow. The sides of wet stones cannot console me, Nor the moss, wound with the last light. If only I could nudge you from this sleep, My maimed darling, my skittery pigeon. -

Theology Between God and the Excluded: Challenges to the Church in the Twenty-First Century

Theology between God and the Excluded: Challenges to the Church in the Twenty-First Century A Doctor of Ministry Course Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University January 2016 Instructor: Dr. Joerg Rieger, Wendland-Cook Professor of Constructive Theology 312B Selecman Hall Phone: (214) 768-2356 Fax: (214) 768-1042 e-mail: [email protected] Course Description: A comparison of major modes of contemporary theology in light of the church’s location between God and the increasing numbers of persons excluded from the resources of life. The course will work towards the development of new constructive and inclusive theological paradigms for ministry. Schedule of Sessions and Readings: Theology turning to the self January 5 Where we are: Theology, exclusion, and the lure of money Reading: Joerg Rieger, God and the Excluded: Visions and Blindspots in Contemporary Theology, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2001, introduction. Joerg Rieger, “Watch the Money” in: Joerg Rieger, ed., Liberating the Future: God, Mammon, and Theology, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1998. January 6 Widening the circle of theology and the church: Liberal theology Reading: Friedrich Schleiermacher, On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers, transl. John Oman (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1994), speeches 2 and 5 (on electronic reserve). Rieger, God and the Excluded, chapter 1. January 7 1 Modernity and empire Reading: Joerg Rieger, Christ and Empire: From Paul to Postcolonial Times, Minneapolis, Fortress Press, 2007, chapter 5 (on electronic reserve). _______________________ Theology turning to the divine and to the texts of the church January 8 Postmodernity and global capitalism Reading: Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity, 3-66, 121-124, 173-188, 327-359 (on electronic reserve). -

Earl Lovelace and the Task of •Œrescuing the Futureâ•Š

Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal Volume 4 Article 8 Issue 2 Earl Lovelace: A Special Issue December 2006 The aN tion/A World/A Place to be Human: Earl Lovelace and the Task of “Rescuing the Future” Jennifer Rahim [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium Recommended Citation Rahim, Jennifer (2006) "The aN tion/A World/A Place to be Human: Earl Lovelace and the Task of “Rescuing the Future”," Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium/vol4/iss2/8 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rahim: The Nation/A World/A Place to be Human: Earl Lovelace and the... Earl Lovelace’s fiction and public addresses1 are preoccupied with two interdependent subjects. The first is Europe’s colonization of the New World, which brought diverse peoples together under severe conditions of systematized inequality. The second is the unique cultural shape this ingathering generated in Caribbean societies and the invitation its continued evolution holds out to citizens to create a different future, not only for them, but also for the world. For Lovelace, therefore, the saving irony of the region’s terrible history is precisely this meeting of so many peoples who, consciously or not, have been “all geared to the New World challenge” (Growing in the Dark 226).