WOLE SOYINKA's OGUN ABIBIMAN by Tanure Ojaide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wolverine & the X-Men: Tommorow Never Leaves Volume 1 Free

FREE WOLVERINE & THE X-MEN: TOMMOROW NEVER LEAVES VOLUME 1 PDF Jason LaTour,Mahmud A. Asrar | 144 pages | 18 Nov 2014 | Marvel Comics | 9780785189923 | English | New York, United States 9 Best X-Men images | x men, jim lee art, marvel comics covers Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge Wolverine & the X-Men: Tommorow Never Leaves Volume 1. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Mahmud Asrar Illustrator. Welcome to the Jean Grey School of Higher Learning, where Wolverine, Storm, and a star-studded faculty educate the next generation of mutants! But with their own lives steeped in deadly enemies and personal crises, how can the X-Men guide and educate - let alone defend - the school? And what mysterious organization waits in the shadows to destroy Wolverine's mutant sanctua Welcome to the Jean Grey School of Higher Learning, where Wolverine, Storm, and a star-studded faculty educate the next generation of Wolverine & the X-Men: Tommorow Never Leaves Volume 1 And what mysterious organization waits in the shadows to destroy Wolverine's mutant sanctuary? The mysterious Phoenix Corporati on wants Quentin Quire, but why? And only Evan can save Fantomex from certain death - but dare he? Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published November 18th by Marvel first published November 1st More Details Original Title. Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. -

Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S

Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S. Davis and Michael Nacht, editors Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory February 2018 Disclaimer: This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, nor any of their employees makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. LLNL-BOOK-746803 Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue: Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S. Davis and Michael Nacht, editors Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory February -

AP Poetry Prompts with the Poems

MsEffie’s List of Poetry Essay Prompts for Advanced Placement® English Literature Exams, 1970-2019* *Advanced Placement® is a trademark registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse, this website. Each poem is included in the following prompts, printed on separate pages for better use in the classroom. None of the prompts are original to me, but are Advanced Placement® English Literature and Composition Exam prompts. This is my best effort to comply with College Board’s use requirements. 1970 Poem: “Elegy for Jane” (Theodore Roethke) Prompt: Write an essay in which you describe the speaker’s attitude toward his former student, Jane. Elegy for Jane by Theodore Roethke I remember the neckcurls, limp and damp as tendrils; And her quick look, a sidelong pickerel smile; And how, once startled into talk, the light syllables leaped for her, And she balanced in the delight of her thought, 5 A wren, happy, tail into the wind, Her song trembling the twigs and small branches. The shade sang with her; The leaves, their whispers turned to kissing, And the mould sang in the bleached valleys under the rose. 10 Oh, when she was sad, she cast herself down into such a pure depth, Even a father could not find her: Scraping her cheek against straw, Stirring the clearest water. My sparrow, you are not here, 15 Waiting like a fern, making a spiney shadow. The sides of wet stones cannot console me, Nor the moss, wound with the last light. If only I could nudge you from this sleep, My maimed darling, my skittery pigeon. -

Wolverine Free

FREE WOLVERINE PDF Chris Claremont,Frank Miller,Dr. Paul Smith | 144 pages | 18 Mar 2009 | Marvel Comics | 9780785137245 | English | New York, United States Người sói Wolverine – Wikipedia tiếng Việt Logan's life began Wolverine Cold Lake, AlbertaCanadasometime between and As a boy, James was notably frail and prone to bouts of allergic Wolverine. He was largely neglected by his mother, who had been institutionalized for a time Wolverine the Wolverine of her first son, John Jr. James spent most of his early years on the Howlett Estate grounds with two playmates that Wolverine at the estate with him: Wolverine O'Haraa red-headed Irish girl who was brought in from town to be a companion to young James, and a boy nicknamed "Dog"Thomas Logan's son and James's half-brother. The children were close friends, but, as they reached Wolverine, the abuse inflicted upon Dog warped Wolverine mind. Dog made unwanted advances towards Rose, which James reported to his father. In retaliation, Dog killed James' puppy, leading to the expulsion of Thomas and Dog from the estate. Thomas, in a Wolverine stupor and armed with a shotgun, invaded Wolverine Howlett Estate with his son and attempted to take his former lover Elizabeth with him. John, Sr. James had just entered Wolverine room when this occurred and his mutation finally manifested: bone claws extended from the backs of his hands Wolverine he attacked the intruders with uncharacteristic ferocity, killing Thomas and scarring Dog's face with three claw marks. The duo then found themselves in the Yukon Territories in Canada, taking refuge in a British Columbia stone quarry, under the guise of being cousins. -

Marvel Universe Thor Comic Reader 1 110 Marvel Universe Thor Comic Reader 2 110 Marvel Universe Thor Digest 110 Marvel Universe Ultimate Spider-Man Vol

AT A GLANCE Since it S inception, Marvel coMicS ha S been defined by hard-hitting action, co Mplex character S, engroSSing Story line S and — above all — heroi SM at itS fine St. get the Scoop on Marvel S’S MoSt popular characterS with thi S ea Sy-to-follow road Map to their greate St adventure S. available fall 2013! THE AVENGERS Iron Man! Thor! Captain America! Hulk! Black Widow! Hawkeye! They are Earth’s Mightiest Heroes, pledged to protect the planet from its most powerful threats! AVENGERS: ENDLESS WARTIME OGN-HC 40 AVENGERS VOL. 3: PRELUDE TO INFINITY PREMIERE HC 52 NEW AVENGERS: BREAKOUT PROSE NOVEL MASS MARKET PAPERBACK 67 NEW AVENGERS BY BRIAN MICHAEL BENDIS VOL. 5 TPB 13 SECRET AVENGERS VOL. 1: REVERIE TPB 10 UNCANNY AVENGERS VOL. 2: RAGNAROK NOW PREMIERE HC 73 YOUNG AVENGERS VOL. 1: STYLE > SUBSTANCE TPB 11 IRON MAN A tech genius, a billionaire, a debonair playboy — Tony Stark is many things. But more than any other, he is the Armored Avenger — Iron Man! With his ever-evolving armor, Iron Man is a leader among the Avengers while valiantly opposing his own formidable gallery of rogues! IRON MAN VOL. 3: THE SECRET ORIGIN OF TONY STARK BOOK 2 PREMIERE HC 90 THOR He is the son of Odin, the scion of Asgard, the brother of Loki and the God of Thunder! He is Thor, the mightiest hero of the Nine Realms and protector of mortals on Earth — from threats born across the universe or deep within the hellish pits of Surtur the Fire Demon. -

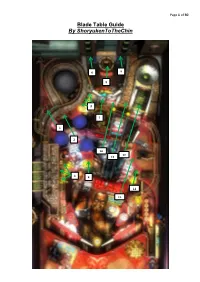

Blade Table Guide by Shoryukentothechin

Page 1 of 30 Blade Table Guide By ShoryukenToTheChin 6 9 8 5 7 1 2 10 12 11 3 4 14 13 Page 2 of 30 Key to Table Overhead Image – Thanks to Cloda on the Zen Studios Forums for the Image 1. Hidden Sink Hole 2. Citadel Ramp 3. Treasure Sink Holes 4. Lair Sink Hole 5. Multiplier Sink Holes/Targets 6. Left Fire Orbit 7. Shrine Sink Hole 8. Mission Sink Hole 9. Right Fire Orbit 10. Left Orbit 11. Alley Ramp 12. Right Orbit 13. Sewer Ramp 14. Lock Sink Hole In this guide when I mention a Ramp etc. I will put a number in brackets which will correspond to the above Key, so that you know where on the table that particular feature is located. TABLE SPECIFICS INTRODUCTION This Table came as the first of the Marvel Pinball 4 Pack dubbed the Marvel Pinball: Core Pack; which came with Tables such as Wolverine, Spiderman & Iron Man. In my opinion is for me the most complex out of the Pack because it has a Day/Night Cycle which certain features can only be accessed during specific Cycles. It’s one of the most inventive features Zen has incorporated into a Table, thus it makes Blade very unique and a Fan favourite when it comes to Marvel Pinball. Notice: This Guide is based off of the Zen Pinball 2 (PS3/Vita) version of the Table on default controls. Some of the controls will be different on the other versions (Pinball FX 2, Marvel Pinball, and Marvel Pinball 3D, etc...), but everything else in the Guide remains the same. -

'Standardized Chapel Library Project' Lists

Standardized Library Resources: Baha’i Print Media: 1) The Hidden Words by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 193184707X; ISBN-13: 978-1931847070) Baha’i Publishing (November 2002) A slim book of short verses, originally written in Arabic and Persian, which reflect the “inner essence” of the religious teachings of all the Prophets of God. 2) Gleanings from the Writings of Baha’u’llah by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847223; ISBN-13: 978-1931847223) Baha’i Publishing (December 2005) Selected passages representing important themes in Baha’u’llah’s writings, such as spiritual evolution, justice, peace, harmony between races and peoples of the world, and the transformation of the individual and society. 3) Some Answered Questions by Abdul-Baham, Laura Clifford Barney and Leslie A. Loveless (ISBN-10: 0877431906; ISBN-13 978-0877431909) Baha’i Publishing, (June 1984) A popular collection of informal “table talks” which address a wide range of spiritual, philosophical, and social questions. 4) The Kitab-i-Iqan Book of Certitude by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847088; ISBN-13: 978:1931847087) Baha’i Publishing (May 2003) Baha’u’llah explains the underlying unity of the world’s religions and the revelations humankind have received from the Prophets of God. 5) God Speaks Again by Kenneth E. Bowers (ISBN-10: 1931847126; ISBN-13: 978- 1931847124) Baha’i Publishing (March 2004) Chronicles the struggles of Baha’u’llah, his voluminous teachings and Baha’u’llah’s legacy which include his teachings for the Baha’i faith. 6) God Passes By by Shoghi Effendi (ISBN-10: 0877430209; ISBN-13: 978-0877430209) Baha’i Publishing (June 1974) A history of the first 100 years of the Baha’i faith, 1844-1944 written by its appointed guardian. -

This Session Will Be Begin Closing at 6PM on 6/12/21, So Be Sure to Get Those Bids in Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook & Twitter @Back2past for Updates

6/12 Keys to the Kingdom: Silver to Modern Comics 6/12/2021 This session will be begin closing at 6PM on 6/12/21, so be sure to get those bids in via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook & Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast! See site for full terms. LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Policies 1 13 New Avengers #40/Sealed Subscription Copy 1 1st appearance of the Skrull Queen Veranke. NM condition. 2 Wolverine #1-4/1982/Limited Series 1 Complete 4-part Series by Chris Claremont & Frank Miller. 1st 14 Wolverine #88/1994/Marvel 1 appearance of Yukio. VG+/FN- condition. Classic Adam Kubert Deadpool cover. NM- condition. 3 Marvel Team-Up #141/1984/KEY 1 15 Uncanny X-Men Annual #14/CBCS 9.4 NM 1 2nd appearance of Spider-Man's black suit. VG+/FN- condition. 1st cameo appearance of Gambit. 4 Wolverine #10/1989/Sabretooth 1 16 Fangoria Horror Magazine Lot of (20) 1 Classic Sabretooth battle. Bill Sienkiewicz cover. NM-/NM with Issues #51-56 & #70-83. 1986-1989. VF to NM condition. slight spine roll. 17 Spider-Man #1/1990/Marvel 1 5 Marvel Team-Up #130-140, 142-150 Comic Lot of (20) 1 Classic 1st issue of the Todd McFarlane run. "Green" cover 20-issue lot. Includes #131, 1st appearance of White Rabbit and version. NM condition. #150 is the final issue. -

The IAFOR Journal of Arts and Humanities – Volume 6 – Issue 2

the iafor journal of arts & humanities Volume 6 – Issue 2 – Autumn 2019 Editor: Alfonso J. García Osuna ISSN: 2187-0616 iafor The IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 6 – Issue – 2 IAFOR Publications IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities Editor Alfonso J. García Osuna, Hofstra University, USA Editorial Board Rodolfo González, Nassau College, State University of New York, USA Anna Hamling, University of New Brunswick, Canada Sabine Loucif, Hofstra University, USA Margarita Esther Sánchez Cuervo, Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain Minni Sawhney, University of Delhi, India Er-Win Tan, Keimyung University, Korea Nour Seblini, Wayne State University, USA Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Publications Manager: Nick Potts IAFOR Publications Sakae 1-16-26 – 201, Naka Ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 6 – Issue 2 – Autumn 2019 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2019 ISSN: 2187-0616 Online: ijah.iafor.org Cover Image: Markus Spiske, Unsplash IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 6 – Issue 2 – Autumn 2019 Edited by Alfonso J. García Osuna Table of Contents Introduction 1 Alfonso J. García Osuna The Philological Impact of Biblical Hebrew on the English Language 3 Gloria Wiederkehr-Pollack From Anti-hero to Commodity: The Legacy of Kurt Cobain 21 Paul Ziek Mirjana Pantic Naderi’s The Runner: A Cinema of Hope Amidst Despair 31 K. Neethu Tilakan The “God, Where Art Thou?” Theme in the Literary Works of 39 Auschwitz Survivors Ka-Tsetnik, Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel Lily Halpert Zamir Awareness and Usage of Social Media by Undergraduates in 49 Selected Universities in Ogun State Olubunmi Adekonojo B. -

The Post-Colonial Christ Paradox: Literary Transfigurations of A

The Post-colonial Christ Paradox: Literary Transfigurations of a Trickster God Gurbir Singh Jolly A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Graduate Program in Humanities York University Toronto, Ontario May 2019 © Gurbir Singh Jolly, 2019 Abstract Within English post-colonial literary studies, Christianity has often been characterized as principally a colonial imposition and, therefore, only modestly theorized as a post-colonial religion that lends itself to complex post- colonial literary renderings. However, the literary implications of post-colonial Christianity will demand increasing attention as Christianity, according to demographic trends, will over the course of the twenty-first century be practiced more widely by peoples who fall under the rubric of post-colonial studies than by peoples of European ancestry. My dissertation considers how four texts—Thomas King’s 1993 novel, Green Grass Running Water, Derek Walcott’s 1967 play, The Dream on Monkey Mountain, Arundhati Roy’s 1996 novel, The God of Small Things, and Chigozie Obioma’s 2015 novel, The Fishermen—feature Christ-like figures whose post-colonial significance resides in the classical Christological paradoxes with which each is identified. Critically, each of these texts pairs Christological paradoxes with paradoxes associated with pre- colonial trickster figures or trickster spirituality. In imagining the Christ as a paradoxical, post-colonial trickster, my core texts address ambiguities and anxieties attending post-colonial pursuits of empowerment. The mixture of Christological and trickster paradoxes in these texts questions post-colonial understandings of power that remain constrained within a colonially-reinforced imaginary inclined to recognize power chiefly as an exercise in subjugation. -

Political Comics and Graphic Novels

POLITICAL COMICS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS Political comics and Graphic Novels Erasmus/WNPiSM/OGUN Lecture 1 POLITICAL COMICS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS LECTURER Wojciech Lewandowski, PhD, DSc Department of Political Theory and Political Thought Faculty of Political Science and International Studies University of Warsaw e-mail: [email protected] www: Imaginaria FB: @imaginariaWL Twitter: @ImaginariaWL DURATION Days and hours: • Mondays, 9:45-11:15 • Office hours: Mondays, 11.30-13.00 (link will be provided on Google Classroom) Place: Online course Academic Year: 2020/2021 Summer term: 30 h EVALUATION 1. Short assignment on Google Classroom (10 points). 2. Take-Home Quiz (30 points). 3. Presence (highly recommended J). 2 POLITICAL COMICS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS LITERATURE AND COURSE MATERIALS Essential readings will be provided on Google Classroom. Some further readings as well as recommended comics and graphic novels will also be provided on Google Classroom whenever possible. Due to the copyright restriction students are not allowed to share received course materials with third parties. Presentations will be made available to students here. They will be removed from the site at the end of the term. COURSE POLICIES Classes are taking place via Zoom application. During the classes students’ cameras might be turned on. Students are obliged to use their name and surname while logging to the meeting. Please make sure, you are not using any nicknames. Presence will be registered by Zoom application. GOOGLE CLASSROM AND ZOOM In order to be able to use all the features of Google Classroom you need to log in with your University email (@student.uw.edu.pl). -

ESIA of Lagos and Ogun States Transmission Project

ESIA of Lagos and Ogun States Transmission Project ESIA OF LAGOS AND OGUN STATES TRANSMISSION LINES AND ASSOCIATED SUBSTATIONS PROJECT (LOT 3) FINAL REPORT Submitted to: Federal Ministry of Environment Environment House Independence Avenue, CBD, Abuja Submitted by: Plot 14, Zambezi Crescent Off Aguiyi Ironsi Street Maitama, Abuja, Nigeria Page i of 455 ESIA of Lagos and Ogun States Transmission Project ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF LAGOS AND OGUN STATES TRANSMISSION LINES AND ASSOCIATED SUBSTATIONS PROJECT (LOT3) Project # 097-002-053 Doc. #: 097-002-053-03 Version 3.0 Prepared by: See List of preparers Engr. Mamoud Bello Abubakar Approved by: No 5, Eldoret Close, Off Aminu Kano Crescent, Wuse 2, Abuja. Nigeria; [email protected]; www.eemslimited.com; +234 80994206008 Page | ii ESIA of Lagos and Ogun States Transmission Project TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ xii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... xv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................................... xvii LIST OF EIA PREPARERS ...................................................................................................... xxiv SUPPORT TEAM .................................................................................................................. xxiv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .........................................................................................................