Political Comics and Graphic Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Alan Moore's Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics

Alan Moore’s Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics Jeremy Larance Introduction On May 26, 2014, Marvel Comics ran a full-page advertisement in the New York Times for Alan Moore’s Miracleman, Book One: A Dream of Flying, calling the work “the series that redefined comics… in print for the first time in over 20 years.” Such an ad, particularly one of this size, is a rare move for the comic book industry in general but one especially rare for a graphic novel consisting primarily of just four comic books originally published over thirty years before- hand. Of course, it helps that the series’ author is a profitable lumi- nary such as Moore, but the advertisement inexplicably makes no reference to Moore at all. Instead, Marvel uses a blurb from Time to establish the reputation of its “new” re-release: “A must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” That line came from an article written by Graeme McMillan, but it is worth noting that McMillan’s full quote from the original article begins with a specific reference to Moore: “[Miracleman] represents, thanks to an erratic publishing schedule that both predated and fol- lowed Moore’s own Watchmen, Moore’s simultaneous first and last words on ‘realism’ in superhero comics—something that makes it a must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” Marvel’s excerpt, in other words, leaves out the very thing that McMillan claims is the most important aspect of Miracle- man’s critical reputation as a “missing link” in the study of Moore’s influence on the superhero genre and on the “medium as a whole.” To be fair to Marvel, for reasons that will be explained below, Moore refused to have his name associated with the Miracleman reprints, so the company was legally obligated to leave his name off of all advertisements. -

Oktober 1968 CM # 005 (20 Seiten) Autor: Arnold Drake, Zeichner: Don Heck, Inker: John Tartaglione Hit Comics Nr. 203 , 1970 Rä

CAPTAIN MARVEL Checkliste (klassische Deutsche Ausgaben 1967-1977) Marvel Super-Heroes (Vol. 1) # 12-13 Oktober 1968 (Dezember 1967 - März 1968) CM # 005“The Mark Of The Metazoid!” (20 Seiten) Captain Marvel (Vol. 1) # 1-14 Autor: Arnold Drake, Zeichner: Don Heck, (Mai 1968 - Juli 1969) Inker: John Tartaglione Hit Comics Nr. 203 Dezember 1967 „Der Angriff des Metazoids“, 1970 MSH # 12“The Coming Of Captain Marvel!” (15 Seiten) Autor: Stan Lee, Zeichner: Gene Colan, Inker: Frank Giacoia Rächer Nr. 12-15„Das Los des Metazoiden!“ , (keine deutsche Veröffentlichung) Dezember 1974-März 1975 Übersetzung: Hartmut Huff, März 1968 Lettering: C. Raschke/U. Mordek/ MSH # 13“Where Stalks The Sentry!” (20 Seiten) M. Gerson/U. Mordek Autor: Roy Thomas, Zeichner: Gene Colan, Inker: Paul Reinman November 1968 (keine deutsche Veröffentlichung) CM # 006“In The Path Of Solam!” (20 Seiten) Autor: Arnold Drake, Zeichner: Don Heck, Mai 1968 Inker: John Tartaglione CM # 001“Out Of The Holocaust - - A Hero!” (21 Seiten) Hit Comics Nr. 203 Autor: Roy Thomas, Zeichner: Gene Colan, „Die Macht des Solams“, 1970 Inker: Vince Colletta Hit Comics Nr. 121 Rächer Nr. 16-18„Auf Solams Spur!“ , „Ein Sieger ohnegleichen“, 1969 April-Juni 1975 Übersetzung: Hartmut Huff, Rächer Nr. 1-3„Der Kampf der Titanen!“ , Lettering: Marlies Gerson, Januar-März 1974 Ursula Mordek (Rächer 16) Lettering: Ursula Mordek (nur Seite 1-7) (Originalseite 15 fehlt) Juli 1968 CM # 002 “From The Void Of Space Comes-- The Super Skrull!” (20 Seiten) Autor: Roy Thomas, Zeichner: Gene Colan, Inker: Vince Colletta Hit Comics Nr. 121 „Der Angriff des Super-Skrull“, 1969 Rächer Nr. -

BREAKING Newsrockville, MD August 19, 2019

MEDIA KIT BREAKING NEWS Rockville, MD August 19, 2019 THE BOYS by Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson Coming to GraphicAudio® A Movie in Your Mind® in Early 2020 GraphicAudio® is thrilled to announce a just inked deal with DYNAMITE COMICS to produce and publish all 6 Omnibus Volumes of THE BOYS directly from the comics and scripted and produced in their unique audio entertainment format. The creative team at GraphicAudio® plans to make the adaptations as faithful as possible to the Graphic Novel series. The series is set between 2006–2008 in a world where superheroes exist. However, most of the su- perheroes in the series' universe are corrupted by their celebrity status and often engage in reckless behavior, compromising the safety of the world. The story follows a small clandestine CIA squad, informally known as "The Boys", led by Butcher and also consisting of Mother's Milk, the French- man, the Female, and new addition "Wee" Hughie Campbell, who are charged with monitoring the superhero community, often leading to gruesome confrontations and dreadful results; in parallel, a key subplot follows Annie "Starlight" January, a young and naive superhero who joins the Seven, the most prestigious– and corrupted – superhero group in the world and The Boys' most powerful enemies. Amazon Prime released THE BOYS Season 1 last month. Joseph Rybandt, Executive Editor of Dynamite and Editor of The Boys says, “While I did not grow up anywhere near the Golden Age of Radio, I have loved the medium of radio and audio dramas almost my entire life. Podcasts make my commute bearable to this day. -

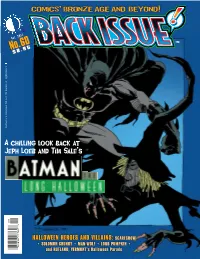

A Chilling Look Back at Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale's

Jeph Loeb Sale and Tim at A back chilling look Batman and Scarecrow TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 No.60 Oct. 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 COMiCs HALLOWEEN HEROES AND VILLAINS: • SOLOMON GRUNDY • MAN-WOLF • LORD PUMPKIN • and RUTLAND, VERMONT’s Halloween Parade , bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD ’ s SCARECROW i . Volume 1, Number 60 October 2012 Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! The Retro Comics Experience! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Tim Sale COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Scott Andrews Tony Isabella Frank Balkin David Anthony Kraft Mike W. Barr Josh Kushins BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Bat-Blog Aaron Lopresti FLASHBACK: Looking Back at Batman: The Long Halloween . .3 Al Bradford Robert Menzies Tim Sale and Greg Wright recall working with Jeph Loeb on this landmark series Jarrod Buttery Dennis O’Neil INTERVIEW: It’s a Matter of Color: with Gregory Wright . .14 Dewey Cassell James Robinson The celebrated color artist (and writer and editor) discusses his interpretations of Tim Sale’s art Nicholas Connor Jerry Robinson Estate Gerry Conway Patrick Robinson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Scarecrow . .19 Bob Cosgrove Rootology The history of one of Batman’s oldest foes, with comments from Barr, Davis, Friedrich, Grant, Jonathan Crane Brian Sagar and O’Neil, plus Golden Age great Jerry Robinson in one of his last interviews Dan Danko Tim Sale FLASHBACK: Marvel Comics’ Scarecrow . .31 Alan Davis Bill Schelly Yep, there was another Scarecrow in comics—an anti-hero with a patchy career at Marvel DC Comics John Schwirian PRINCE STREET NEWS: A Visit to the (Great) Pumpkin Patch . -

WOLE SOYINKA's OGUN ABIBIMAN by Tanure Ojaide

WOLE SOYINKA'S OGUN ABIBIMAN By Tanure Ojaide Thomas Mofolo's Chaka seems to have set a literary trail in Africa, and Shaka has been the subject of many plays and poems. Shaka, the Zulu king, "is seen primarily as a romantic figure in Francophone Africa, as a military figure in Southern Africa. ul Moreover, "the extensive Shaka literature in Africa illustrates the desire of African writers to seek in Africa's past a source that will be relevant to contemporary realities "2 Shaka was a great military leader who restored dignity to his people, the sort of leadership needed in the liberation struggle in Southern Africa. Chaka is political, and "can be considered an extended praise song singing the deeds of this heroic Zulu leader; it can be regarded as an African epic cele brating the founding of an empire. u3 It is ironic that Wole Soyinka' s Ogun Abibi.man appeared the same year, 1976, that Donald Burness published his book on Shaka in African literature, writing that "Although Shaka is alluded to, for instance, in Soyinka's A Dance of the Forest~ the Zulu king appears very seldom in Nigerian literature. " Soyinka's Ogun Abibiman relies on Mofolo's Chaka and its military tradition together with the 0gun myth in the exhorta tion of black people fighting for freedom and human rights in Southern Africa. Ogun is a war-god, and the bringing together of Ogun and Shaka is necessary to fuse the best in Africa's military experience. Though the two have records of wanton killings at one time in their military careers, they, neverthe less, are mythically and historically, perhaps, the greatest warlords in Africa. -

Don Martin Dies, Maddest of Mad Magazine Cartoonists

The Miami Herald January 8, 2000 Saturday DON MARTIN DIES, MADDEST OF MAD MAGAZINE CARTOONISTS BY DANIEL de VISE AND JASMINE KRIPALANI Don Martin was the man who put the Mad in Mad magazine. He drew edgy cartoons about hapless goofs with anvil jaws and hinged feet who usually met violent fates, sometimes with a nerve-shredding SHTOINK! His absurdist vignettes inspired two or three generations of rebellious teenage boys to hoard dog-eared Mads in closets and beneath beds. He was their secret. Martin died Thursday at Baptist Hospital after battling cancer at his South Dade home. He was 68. Colleagues considered him a genius in the same rank as Robert Crumb (Keep on Truckin') and Gary Larson (The Far Side). But adults seldom saw his work. And Don Martin's slack-jawed goofballs weren't about to pop up on calendars or mugs. The son of a New Jersey school supply salesman, Martin joined the fledgling Mad magazine in 1956 and stayed with the irreverent publication for 31 years. Editors billed him as "Mad's Maddest Cartoonist." "He was a hard-edged Charles Schulz," said Nick Meglin, co-editor of Mad. "It's no surprise that Snoopy got to the moon. And it's no surprise that Don Martin characters would wind up on the wall in some coffeehouse in San Francisco." COUNTERCULTURE HERO If Peanuts was the cartoon of mainstream America - embraced even by Apollo astronauts - then Martin's crazy-haired, oval-nosed boobs were heroes of the counterculture. Gilbert Shelton, an underground cartoonist who penned the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, said Martin was the reason he first picked up the pencil. -

The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick De Don

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS MEMORIA DE LICENCIATURA From Don Quixote to The Tick: The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick ____________ De Don Quijote a The Tick: El Reflejo de Sancho Panza en el sidekick del Cómic Autor: José Manuel Annacondia López Directora: Dra. María José Álvarez Faedo VºBº: Oviedo, 2012 To comic book creators of yesterday, today and tomorrow. The comics medium is a very specialized area of the Arts, home to many rare and talented blooms and flowering imaginations and it breaks my heart to see so many of our best and brightest bowing down to the same market pressures which drive lowest-common-denominator blockbuster movies and television cop shows. Let's see if we can call time on this trend by demanding and creating big, wild comics which stretch our imaginations. Let's make living breathing, sprawling adventures filled with mind-blowing images of things unseen on Earth. Let's make artefacts that are not faux-games or movies but something other, something so rare and strange it might as well be a window into another universe because that's what it is. [Grant Morrison, “Grant Morrison: Master & Commander” (2004: 2)] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements v 2. Introduction 1 3. Chapter I: Theoretical Background 6 4. Chapter II: The Nature of Comic Books 11 5. Chapter III: Heroes Defined 18 6. Chapter IV: Enter the Sidekick 30 7. Chapter V: Dark Knights of Sad Countenances 35 8. Chapter VI: Under Scrutiny 53 9. Chapter VII: Evolve or Die 67 10. -

Ownvoices and Small Press Comics

#OwnVoices and Small Press Comics Reader’s Advisory Hello! Presenters: Amanda Hua, Children’s Librarian, The Seattle Public Library Nathalie Gelms, Youth Services Librarian, Sno-Isle Libraries Aydin Kwan, Assistant Manager, Outsider Comics and Geek Boutique 2 Let’s Meet Your Neighbors! Exquisite Corpse The Rules: • Teams of four, please. • Fold the paper in half twice to make four long rectangles. • Every team should have a clipboard, paper, and • First person draw a head and neck. pencils. • Second person draw a torso. • We will draw a body in • Third person draw legs. teams without seeing • Fourth person draw feet and ground. what the other person drew. 3 4 Up next: • #OwnVoices Definition and History • Comic Book Publishing • Resources for finding #OwnVoices and Small Press comics • Our favorite comics • Your favorite comics! 5 “This is saying our generation will never matter. But we have to matter. If we don’t, there is no future worth saving.” – Ms. Marvel #10, Civil War Vol. 2 6 #OwnVoices: A History Author Corinne Duyvis created the # on twitter “to recommend kidlit about diverse characters written by authors from that same diverse group,” (Duyvis, 2015). http://www.corinneduyvis.net/ownvoices/ 7 Comic Book Publishing × Major publishers and our big vendors often determine selection for libraries. × To make sure our collections are representative of all of our patrons, however, we need to explore other options. 8 What is small press? —Spike Trotman, Iron Circus Comics 9 #OwnVoices Publishers at a glance Small Press Small-ish Press -

Microsoft Visual Basic

$ LIST: FAX/MODEM/E-MAIL: aug 23 2021 PREVIEWS DISK: aug 25 2021 [email protected] for News, Specials and Reorders Visit WWW.PEPCOMICS.NL PEP COMICS DUE DATE: DCD WETH. DEN OUDESTRAAT 10 FAX: 23 augustus 5706 ST HELMOND ONLINE: 23 augustus TEL +31 (0)492-472760 SHIPPING: ($) FAX +31 (0)492-472761 oktober/november #557 ********************************** __ 0079 Walking Dead Compendium TPB Vol.04 59.99 A *** DIAMOND COMIC DISTR. ******* __ 0080 [M] Walking Dead Heres Negan H/C 19.99 A ********************************** __ 0081 [M] Walking Dead Alien H/C 19.99 A __ 0082 Ess.Guide To Comic Bk Letterin S/C 16.99 A DCD SALES TOOLS page 026 __ 0083 Howtoons Tools/Mass Constructi TPB 17.99 A __ 0019 Previews October 2021 #397 5.00 D __ 0084 Howtoons Reignition TPB Vol.01 9.99 A __ 0020 Previews October 2021 Custome #397 0.25 D __ 0085 [M] Fine Print TPB Vol.01 16.99 A __ 0021 Previews Oct 2021 Custo EXTRA #397 0.50 D __ 0086 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.01 14.99 A __ 0023 Previews Oct 2021 Retai EXTRA #397 2.08 D __ 0087 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.02 14.99 A __ 0024 Game Trade Magazine #260 0.00 N __ 0088 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.03 14.99 A __ 0025 Game Trade Magazine EXTRA #260 0.58 N __ 0089 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.04 14.99 A __ 0026 Marvel Previews O EXTRA Vol.05 #16 0.00 D __ 0090 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.05 14.99 A IMAGE COMICS page 040 __ 0091 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.06 16.99 A __ 0028 [M] Friday Bk 01 First Day/Chr TPB 14.99 A __ 0092 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.07 16.99 A __ 0029 [M] Private Eye H/C DLX 49.99 A __ 0093 [M] Sunstone Book 01 H/C 39.99 A __ 0030 [M] Reckless -

Nieuwigheden Anderstalige Strips 2014

NIEUWIGHEDEN ANDERSTALIGE STRIPS 2014 WEEK 2 Engels All New X-Men 1: Yesterday’s X-Men (€ 19,99) (Stuart Immonen & Brian Mickael Bendis / Marvel) All New X-Men / Superior Spider-Men / Indestructible Hulk: The Arms of The Octopus (€ 14,99) (Kris Anka & Mike Costa / Marvel) Avengers A.I.: Human After All (€ 16, 99) (André Araujo & Sam Humphries / Marvel) Batman: Arkham Unhinged (€ 14,99) (David Lopez & Derek Fridols / DC Comics) Batman Detective Comics 2: Scare Tactics (€ 16,99) (Tony S. Daniel / DC Comics) Batman: The Dark Knight 2: Cycle of Violence (€ 14,99) (David Finch & Gregg Hurwitz / DC Comics) Batman: The TV Stories (€ 14,99) (Diverse auteurs / DC Comics) Fantastic Four / Inhumans: Atlantis Rising (€ 39,99) (Diverse auteurs / Marvel) Simpsons Comics: Shake-Up (€ 15,99) (Studio Matt Groening / Bongo Comics) Star Wars Omnibus: Adventures (€ 24,99) (Diverse auteurs / Dark Horse) Star Wars Omnibus: Dark Times (€ 24,99) (Diverse auteurs / Dark Horse) Superior Spider-Men Team-Up: Friendly Fire (€ 17,99) (Diverse auteurs / Marvel) Swamp Thing 1 (€ 19,99) (Roger Peterson & Brian K. Vaughan / Vertigo) The Best of Wonder Wart-Hog (€ 29,95) (Gilbert Shelton / Knockabout) West Coast Avengers: Sins of the Past (€ 29,99) (Al Milgrom & Steve Englehart / Marvel) Manga – Engelstalig: Naruto 64 (€ 9,99) (Masashi Kishimoto / Viz) Naruto: Three-in-One 7 (€ 14,99) (Masashi Kishimoto / Viz) Marvel Omnibussen in aanbieding !!! Avengers: West Coast Avengers vol. 1 $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! Marvel Now ! $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! Punisher by Rick Remender $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! The Avengers vol. 1 $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! Ultimate Spider-Man: Death of Spider-Man $ 75 NU: 39,99 Euro !!! Untold Tales of Spider-Man $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! X-Force vol.