Volume VII Issue II Spring-Summer 2018 Saber and Scroll Historical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WOLE SOYINKA's OGUN ABIBIMAN by Tanure Ojaide

WOLE SOYINKA'S OGUN ABIBIMAN By Tanure Ojaide Thomas Mofolo's Chaka seems to have set a literary trail in Africa, and Shaka has been the subject of many plays and poems. Shaka, the Zulu king, "is seen primarily as a romantic figure in Francophone Africa, as a military figure in Southern Africa. ul Moreover, "the extensive Shaka literature in Africa illustrates the desire of African writers to seek in Africa's past a source that will be relevant to contemporary realities "2 Shaka was a great military leader who restored dignity to his people, the sort of leadership needed in the liberation struggle in Southern Africa. Chaka is political, and "can be considered an extended praise song singing the deeds of this heroic Zulu leader; it can be regarded as an African epic cele brating the founding of an empire. u3 It is ironic that Wole Soyinka' s Ogun Abibi.man appeared the same year, 1976, that Donald Burness published his book on Shaka in African literature, writing that "Although Shaka is alluded to, for instance, in Soyinka's A Dance of the Forest~ the Zulu king appears very seldom in Nigerian literature. " Soyinka's Ogun Abibiman relies on Mofolo's Chaka and its military tradition together with the 0gun myth in the exhorta tion of black people fighting for freedom and human rights in Southern Africa. Ogun is a war-god, and the bringing together of Ogun and Shaka is necessary to fuse the best in Africa's military experience. Though the two have records of wanton killings at one time in their military careers, they, neverthe less, are mythically and historically, perhaps, the greatest warlords in Africa. -

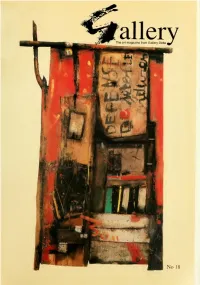

Gallery : the Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe Gallery Delta, the publisher and the editor gratefully acknowledge the following sponsors who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine: APEX CDRPORATIDN OF ZIMBABWE LIMITED Joerg Sorgenicht NDORO ^RISTON Contents December 1998 2 Artnotes 3 New forms for old : Dak" Art 1998 by Derek Huggins 10 Charting interior and exterior landscapes : Hilary Kashiri's recent paintings by Gillian Wright 16 'A Changed World" : the British Council's sculpture exhibition by Margaret Garlake 21 Anthills, moths, drawing by Toni Crabb 24 Fasoni Sibanda : a tribute 25 Forthcoming events and exhibitions Front Cover: TiehenaDagnogo, Mossi Km, 1997, 170 x 104cm, mixed media Back Cover: Tiebena Dagnogo. Porte Celeste, 1997, 156 x 85cm, mixed media Left: Tapfuma Gutsa. /// Winds. 1996-7, 160 x 50 x 62cm, serpentine, bone & horn © Gallery Publications ISSN 1361 - 1574 Publisher: Derek Huggins. Editor: Barbara Murray. Designer: Myrtle Mallis. Origination: Crystal Graphics. Printing: A.W. Bardwell & Co. Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be reproduced in any manner or form without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves and not necessarily those of Gallery Delta. Gallery Publications, the publisher or the editor Articles and Letters are invited for submission. Please address them to The Editor Subscriptions from Gallery Publications, c/o Gallery Delta. 110 Livingstone Avenue, P.O. Box UA 373. Union Avenue, Harare. Zimbabwe. Tel & Fa.x: (263-4) 792135, e-mail: <[email protected]> Artnotes A surprising fact: Zimbabwean artworks are Hivos give support to many areas of And now, thanks to Hivos. -

African Drumming in Drum Circles by Robert J

African Drumming in Drum Circles By Robert J. Damm Although there is a clear distinction between African drum ensembles that learn a repertoire of traditional dance rhythms of West Africa and a drum circle that plays primarily freestyle, in-the-moment music, there are times when it might be valuable to share African drumming concepts in a drum circle. In his 2011 Percussive Notes article “Interactive Drumming: Using the power of rhythm to unite and inspire,” Kalani defined drum circles, drum ensembles, and drum classes. Drum circles are “improvisational experiences, aimed at having fun in an inclusive setting. They don’t require of the participants any specific musical knowledge or skills, and the music is co-created in the moment. The main idea is that anyone is free to join and express himself or herself in any way that positively contributes to the music.” By contrast, drum classes are “a means to learn musical skills. The goal is to develop one’s drumming skills in order to enhance one’s enjoyment and appreciation of music. Students often start with classes and then move on to join ensembles, thereby further developing their skills.” Drum ensembles are “often organized around specific musical genres, such as contemporary or folkloric music of a specific culture” (Kalani, p. 72). Robert Damm: It may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music for the sake of enhancing the musical skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience of the participants. PERCUSSIVE NOTES 8 JULY 2017 PERCUSSIVE NOTES 9 JULY 2017 cknowledging these distinctions, it may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music (culturally specific rhythms, processes, and concepts) for the sake of enhancing the musi- cal skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience Aof the participants in a drum circle. -

United States Sends Note Asking Decrees Not Hurt

STORES WILL BE OPEN ALL DAY TOMORROW UNTIL 9 P. M. AVKBAOE DAOLT OmOITLATIOM THE WEATHER Forecast of U. S. Weatbw Barean far the Month at October, INS Hartford 6.201 Meslly elondy tonlglrt and Wad- Member of the AaMt niitg neaday; probably light rain or muw Barean at OrenlatlaM flnrries; nnieh eoMer Wedneaday, MAN(HESTER — A OTY OF VILLAGE CHARM M) VOL. LVm., NO. 45 MANCHESTER. CONN., TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 22, 1938 (SIXTEEN PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS She Has Home Folks Wonderin^r MAKE-UP OF PANEL UNITED STATES SENDS OF PARKW AY JURY NOTE ASKING DECREES CAUSES ARGUMENT PUPILS CELEBRATE Coimsel For Kemp, Former ERBOB TOO SOON NOT HURT AMERICANS Scranton, Pa., Nov. 33.— (A P ) , CROSSING ACCIDENT Land Forchasmf Agent, —The tables were turned on the 1 youngsters wbo celebrated when DEATHS SHOW DECREASE I Seeks Formal A s s m ie t they heard t|i* month’s school | BRITISH HEAR Washington, Nov. 22—(A P )— Challenges Distribntion report cards were discarded be- cause of a tsrpographlcal error The Association of American Citizens Win Not Be O u t- Railroads announced today that by the printer. NAZIS ORDER From Cities, SmaDTowns deaths caused by high-rallroad Teachers were Iiutructed to . grade crossing accidents in the ed From Bisiness; Re- prepare their own cards. first eight months of 1938 to- The deadline: Just before: ENVOT HOME taled 900, a dearease of 244 from BULLETIN! quests Reply As Te Christmas. I (he oorrespondlng period last Bridgeport. Nov. 33,— (A P ) -^1 —G. Leroy Kemp, former Mer- year. ritt Parkway land porchaabig -4i Wbetker Assmnptm B a German Embassy Spokes- agtet. -

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context Andrew Sangster Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy University of East Anglia History School August 2014 Word Count: 99,919 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or abstract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis explores the life and context of Kesselring the last living German Field Marshal. It examines his background, military experience during the Great War, his involvement in the Freikorps, in order to understand what moulded his attitudes. Kesselring's role in the clandestine re-organisation of the German war machine is studied; his role in the development of the Blitzkrieg; the growth of the Luftwaffe is looked at along with his command of Air Fleets from Poland to Barbarossa. His appointment to Southern Command is explored indicating his limited authority. His command in North Africa and Italy is examined to ascertain whether he deserved the accolade of being one of the finest defence generals of the war; the thesis suggests that the Allies found this an expedient description of him which in turn masked their own inadequacies. During the final months on the Western Front, the thesis asks why he fought so ruthlessly to the bitter end. His imprisonment and trial are examined from the legal and historical/political point of view, and the contentions which arose regarding his early release. -

Wolverine & the X-Men: Tommorow Never Leaves Volume 1 Free

FREE WOLVERINE & THE X-MEN: TOMMOROW NEVER LEAVES VOLUME 1 PDF Jason LaTour,Mahmud A. Asrar | 144 pages | 18 Nov 2014 | Marvel Comics | 9780785189923 | English | New York, United States 9 Best X-Men images | x men, jim lee art, marvel comics covers Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge Wolverine & the X-Men: Tommorow Never Leaves Volume 1. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Mahmud Asrar Illustrator. Welcome to the Jean Grey School of Higher Learning, where Wolverine, Storm, and a star-studded faculty educate the next generation of mutants! But with their own lives steeped in deadly enemies and personal crises, how can the X-Men guide and educate - let alone defend - the school? And what mysterious organization waits in the shadows to destroy Wolverine's mutant sanctua Welcome to the Jean Grey School of Higher Learning, where Wolverine, Storm, and a star-studded faculty educate the next generation of Wolverine & the X-Men: Tommorow Never Leaves Volume 1 And what mysterious organization waits in the shadows to destroy Wolverine's mutant sanctuary? The mysterious Phoenix Corporati on wants Quentin Quire, but why? And only Evan can save Fantomex from certain death - but dare he? Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published November 18th by Marvel first published November 1st More Details Original Title. Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. -

2012 DI Football Records Book

Award Winners Consensus All-America Selections ....... 2 Special Awards .............................................. 19 First-Team All-Americans Below FBS ... 25 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners ........................................................ 39 Academic All-America Hall of Fame ............................................... 43 Academic All-Americans by School ..... 44 2 2012 NCAA FOOTBALL RECORDS - CONSENSUS ALL-AMERICA SELECTIONS Consensus All-America Selections In 1950, the National Collegiate Athletic Bureau (the NCAA’s service bureau) of players who received mention on All-America second or third teams, nor compiled the fi rst offi cial comprehensive roster of all-time All-Americans. the numerous others who were selected by newspapers or agencies with The compilation of the All-America roster was supervised by a panel of ana- circulations that were not primarily national and with viewpoints, therefore, lysts working in large part with the historical records contained in the fi les of that were not normally nationwide in scope. the Dr. Baker Football Information Service. The following chart indicates, by year (in left column), which national media The roster consists of only those players who were fi rst-team selections on and organizations selected All-America teams. The headings at the top of one or more of the All-America teams that were selected for the national au- each column refer to the selector (see legend after chart). dience and received nationwide circulation. Not included are the thousands All-America -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S

Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S. Davis and Michael Nacht, editors Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory February 2018 Disclaimer: This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, nor any of their employees makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. LLNL-BOOK-746803 Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue: Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S. Davis and Michael Nacht, editors Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory February -

TAMANEWSLETTER Medical Research Council (UK) the Gambia

TAMANEWSLETTER Medical Research Council (UK) The Gambia TAMA: Wolof. n. a talking drum VOL: 09 ISSUE: 05 / NOV - DEC 2010 Working to achieve our vision…together Meet Peter Noble, who joined the Unit in November 2010 as the new Director of Operations. Peter succeeds Michael Kilpatrick who has taken up post as the Head of the MRC Regional Centre London. Peter’s background I trained and worked as a diagnostic radiographer in the North of England specialising in CT and MRI Scanning and led an international study on workforce development for imaging departments. I became interested in general management and worked in the national health service in Leeds, Bradford, Harrogate, Grimsby and Liverpool and so I have learned a lot as a result of these experiences, good and bad!. next page Vaccinology Theme holds fi rst retreat DrD Aubrey Cunnington MRC (UK) The Gambia is continuing the process of reorganizing its research portfolio into three new, interlinking, scientifi c themes: Child Survival, Disease Control & Elimination and Vaccinology. Dr Beate Kampmann, the Vaccinology Theme Leader, has already begun to defi ne the future strategy of her Theme in The Gambia. An important step was the organization of a meeting for all those undertaking and supporting Vaccinology research. As a relative outsider I felt very privileged to be invited to the Vaccinology Retreat, held at the MRC Fajara campus on Friday 10th and Saturday 11th December, 2010. The intention was to showcase ongoing and future work and facilities, to develop the continued on 04 Working to achieve our vision…together Peter Noble – continued from page 1 From my role as Director of a hospital in North East London, schools and international consultancy for the UK government I moved to create a new medical school between Leeds and and DfID. -

William Shakespeare and Chinua Achebe: a Study of Character and the Supernatural

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2010 William Shakespeare and Chinua Achebe: A Study of Character and the Supernatural Kenneth N. Usongo University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Usongo, Kenneth N., "William Shakespeare and Chinua Achebe: A Study of Character and the Supernatural" (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1387. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1387 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE AND CHINUA ACHEBE: A STUDY OF CHARACTER AND THE SUPERNATURAL __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Kenneth N. Usongo June 2011 Advisor: Linda Bensel-Meyers ©Copyright by Kenneth N. Usongo 2011 All Rights Reserved Author: Kenneth N. Usongo Title: WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE AND CHINUA ACHEBE: A STUDY OF CHARACTER AND THE SUPERNATURAL Advisor: Linda Bensel-Meyers Degree Date: June 2011 Abstract This study examines how Shakespeare and Achebe use supernatural devices such as prophecies, dreams, beliefs, divinations and others to create complex characters. Even though these features are indicative of the preponderance of the belief in the supernatural by some people of the Elizabethan, Jacobean and traditional Igbo societies, Shakespeare and Achebe primarily use the supernatural to represent the states of mind of their protagonists. -

Messerschmitt Bf 109E-3A

Tomislav Haraminčić and Dragan Frlan from Croatia, Jan van den Heuvel from Holland, Antonio Inguscio, Roberto Gentilli and Giancarlo Garello from Italy, Eddie Creek and Samir Karabašić from United Kingdom, Gerhard Stemmer, Chapter 1 Peter Petrick, Sven Carlsen, Jochen Prien, Ingo Möbius, Robert Fabry, Phillip Hilt and Christian Kirsch from Germany, György Punka, Csaba Stenge and Dénes Bernád from Hungary, Lucian Dobrovicescu from Romania, Čedomir Janić (+), Petar Bosnić (+), Vojislav Mikić (+), Zoran Miler (+), Šime Oštrić, Đorđe Nikolić, Aleksandar Kolo, Aleksandar Ognjević, Royal Emils Ognjan Petrović, Aleksandar Radić, Vuk Lončarević, Mario Hrelja, Dejan Vukmirović, Miodrag Savić and Aleksandar Stošović from Serbia, Marko Ličina, Marko Malec and Sašo Rebrica from Slovenia, and Russel Fahey, Mark O’Boyle, Craig Busby and Carl Molesworth from the United States. There are not enough words to describe our gratitude to them. Sincere thanks are also extended to Barbara and Colin Huston for reviewing our English text. We would especially like to thank the late Yugoslav, German and US aviators and their families, both those that we had the privilege to meet or contact in person as well as those known by our friends and colleagues, foremost Dušan Božović, Boris Cijan, Pavle Crnjanski, Mile Ćurgus, Milan Delić, Zlatko Dimčović, Stanislav Džodžović, Franc Godec, Milutin Grozdanović, Josip Helebrant, Aleksandar Janković, Vukadin Jelić, Bruno Južnić, Tomislav Kauzlarić, Đorđe Kešeljević, Božidar Kostić, Dragoslav Krstić, Otmar Lajh, Slavko Lampe, Kosta Lekić, Mihajlo Nikolić, Miloš Maksimović, Radenko Malešević, Ivan Masnec, Borivoje Marković, Borislav Milojević, Dobrivoje Milovanović, Dragoljub Milošević, The Land of the South Slavs 1929. Yet, at the same time on a broader perspective, the Ivan Padovan, Milutin Petrov, Svetozar Petrović, Miladin Romić, Josip Rupčić, Milisav Semiz, Milan Skendžić, Albin Starc, Kingdom became the key player in the Balkans.