A Study of Modern Messianic Cults (London: Mcgibbon and Kee, 1963); T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

The Meaning of Yoruba Aso Olona Is Far from Water Tight

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1996 THE MEANING OF YORUBA ASO OLONA IS FAR FROM WATER TIGHT Lisa Aronson Skidmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Aronson, Lisa, "THE MEANING OF YORUBA ASO OLONA IS FAR FROM WATER TIGHT" (1996). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 872. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/872 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE MEANING OF YORUBA ASO OLONA IS FAR FROM WATER TIGHT LISA ARONSON Department of Art and Art History Skidmore College Saratoga Springs, NY 12203 While researching the ritual meaning of cloth among the Eastern Ijo of the Niger Delta, I examined the contents of a number of family owned trunks in which were stored old and much valued cloths traded from elsewhere in Africa, Europe, and India. One type of cloth which I frequently found in these collections was this one (See Fig. 1) made up of three, or sometimes four, woven strips that are sewn along the salvage and decorated with supplemental weft-float design. The Eastern Ijo regard this cloth as a valuable heirloom for its trade value and for the fact that its designs evoke spiritual powers associated with the sea .. The Eastern Ijo refer to this particular cloth as ikaki or tortoise, a water spirit (owu) known in Ijo lore for his combination of trickery and wisdom. -

Maiduguri: City Scoping Study

MAIDUGURI: CITY SCOPING STUDY By Marissa Bell and Katja Starc Card (IRC) June 2021 MAIDUGURI: CITY SCOPING STUDY 2 Maiduguri is the largest city in north east Nigeria and the capital of Borno State, which suffers from endemic poverty, and capacity and legitimacy gaps in terms of its governance. The state has been severely affected by the Boko Haram insurgency and the resulting insecurity has led to economic stagnation in Maiduguri. The city has borne the largest burden of support to those displaced by the conflict. The population influx has exacerbated vulnerabilities that existed in the city before the security and displacement crisis, including weak capacities of local governments, poor service provision and high youth unemployment. The Boko Haram insurgency appears to be attempting to fill this gap in governance and service delivery. By exploiting high levels of youth unemployment Boko Haram is strengthening its grip around Maiduguri and perpetuating instability. Maiduguri also faces severe environmental challenges as it is located in the Lake Chad region, where the effects of climate change increasingly manifesting through drought and desertification. Limited access to water and poor water quality is a serious issue in Maiduguri’s vulnerable neighborhoods. A paucity of drains and clogging leads to annual flooding in the wet season. As the population of Maiduguri has grown, many poor households have been forced to take housing in flood-prone areas along drainages due to increased rent prices in other parts of the city. URBAN CONTEXT Maiduguri is the oldest town in north eastern Nigeria and has long served as a commercial centre with links to Niger, Cameroon and Chad and to nomadic communities in the Sahara. -

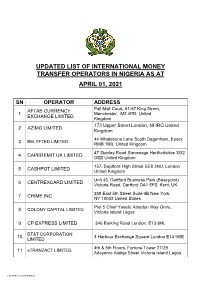

Updated List of International Money Transfer Operators in Nigeria As At

UPDATED LIST OF INTERNATIONAL MONEY TRANSFER OPERATORS IN NIGERIA AS AT APRIL 01, 2021 SN OPERATOR ADDRESS AFTAB CURRENCY Pall Mall Court, 61-67 King Street, 1 Manchester, M2 4PD, United EXCHANGE LIMITED Kingdom 173 Upper Street London, NI IRG United 2 AZIMO LIMITED Kingdom 44 Whalebone Lane South Dagenham, Essex 3 BELYFTED LIMITED RMB 1BB, United Kingdom 47 Stanley Road Stevenage Hertfordshire SG2 4 CAPEREMIT UK LIMITED OEE United Kingdom 157, Deptford High Street SE8 3NU, London 5 CASHPOT LIMITED United Kingdom Unit 46, Dartford Business Park (Basepoint) 6 CENTREXCARD LIMITED Victoria Road, Dartford DA1 5FS, Kent, UK 239 East 5th Street Suite 4B New York, 7 CHIME INC. NY 10003 United States Plot 5 Chief Yesefu Abiodun Way Oniru, 8 COLONY CAPITAL LIMITED Victoria Island Lagos 9 CP EXPRESS LIMITED 346 Barking Road London, E13 8HL DT&T CORPORATION 10 3 Harbour Exchange Square London E14 9GE LIMITED 4th & 5th Floors, Fortune Tower 27/29 11 eTRANZACT LIMITED Adeyemo Alakija Street Victoria Island Lagos Classified as Confidential FIEM GROUP LLC DBA 1327, Empire Central Drive St. 110-6 Dallas 12 PING EXPRESS Texas 6492 Landover Road Suite A1 Landover 13 FIRST APPLE INC. MD20785 Cheverly, USA FLUTTERWAVE 14 TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS 8 Providence Street, Lekki Phase 1 Lagos LIMITED FORTIFIED FRONTS LIMITED 15 in Partnership with e-2-e PAY #15 Glover Road Ikoyi, Lagos LIMITED FUNDS & ELECTRONIC 16 No. 15, Cameron Road, Ikoyi, Lagos TRANSFER SOLUTION FUNTECH GLOBAL Clarendon House 125 Shenley Road 17 COMMUNICATIONS Borehamwood Heartshire WD6 1AG United LIMITED Kingdom GLOBAL CURRENCY 1280 Ashton Old Road Manchester, M11 1JJ 18 TRAVEL & TOURS LIMITED United Kingdom Rue des Colonies 56, 6th Floor-B1000 Brussels 19 HOMESEND S.C.R.L Belgium IDT PAYMENT SERVICES 20 520 Broad Street USA INC. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Open Educational Resources Borough of Manhattan Community College 2021 AFN 121 Yoruba Tradition and Culture Remi Alapo CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bm_oers/29 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Presented as part of the discussion on West Africa about the instructor’s Heritage in the AFN 121 course History of African Civilizations on April 20, 2021. Yoruba Tradition and Culture Prof. Remi Alapo Department of Ethnic and Race Studies Borough of Manhattan Community College [BMCC]. Questions / Comments: [email protected] AFN 121 - History of African Civilizations (Same as HIS 121) Description This course examines African "civilizations" from early antiquity to the decline of the West African Empire of Songhay. Through readings, lectures, discussions and videos, students will be introduced to the major themes and patterns that characterize the various African settlements, states, and empires of antiquity to the close of the seventeenth century. The course explores the wide range of social and cultural as well as technological and economic change in Africa, and interweaves African agricultural, social, political, cultural, technological, and economic history in relation to developments in the rest of the world, in addition to analyzing factors that influenced daily life such as the lens of ecology, food production, disease, social organization and relationships, culture and spiritual practice. -

Nigerian Nationalism: a Case Study in Southern Nigeria, 1885-1939

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1972 Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939 Bassey Edet Ekong Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the African Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ekong, Bassey Edet, "Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939" (1972). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 956. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF' THE 'I'HESIS OF Bassey Edet Skc1::lg for the Master of Arts in History prt:;~'entE!o. 'May l8~ 1972. Title: Nigerian Nationalism: A Case Study In Southern Nigeria 1885-1939. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITIIEE: ranklln G. West Modern Nigeria is a creation of the Britiahl who be cause of economio interest, ignored the existing political, racial, historical, religious and language differences. Tbe task of developing a concept of nationalism from among suoh diverse elements who inhabit Nigeria and speak about 280 tribal languages was immense if not impossible. The tra.ditionalists did their best in opposing the Brltlsh who took away their privileges and traditional rl;hts, but tbeir policy did not countenance nationalism. The rise and growth of nationalism wa3 only po~ sible tbrough educs,ted Africans. -

Law Review Articles

Law Review Articles 1. Church and State in the United States: Competing Conceptions and Historic Changes Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 13 Ind. J. Global Legal Stud. 503 This article explains the separation of church and state in the United States. 2. Crowns and Crosses: The problems of Politico-Religious Visits as they Relate to the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy 3 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 227 This article examines whether the Pope or any similar leader should be treated as a head of state or as the representative of a religious group. 3. Damages and Damocles: The Propriety of Recoupment Orders as Remedies for Violations of the Establishment Clause Notre Dame Law Review 83 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1385 In Americans United for Separation of Church & State v. Prison Fellowship Ministries, the court required “a private party, at the behest of another private party, to reimburse the public treasury when the government itself ha[d] not sought reimbursement” for a violation of the Establishment Clause. This Note offers background about taxpayer standing, restitution lawsuits, and background on the Establishment Clause. 4. Accommodation of Religion in Public Institutions Harvard Law Review 100 Harv. L. Rev. 1639 This artcile examines establishment clause problems attaching to government efforts to recognize religion in public institutions under an ‘accommodation’ rationale. Section A introduces the justification for allowing government recognition of religion in public institutions and discusses the difficulty of applying traditional establishment clause analysis to actions taken under this justification. It then proposes that the ambiguities in establishment clause analysis should be explicitly resolved so as to prevent majoritarian infringements of the religious autonomy of minorities. -

Ikorodu Ilorin

BULLETIN JULY 2016 | VOLUME 2, ISSUE 6 TREE National AHMADIYYA PLANTING Waqar- CONDEMNS D Etai ls inside e Amal FRANCE IKORODU CHURCH APATA ATTACKS ILORIN OSHOGBO AL-IRFAN BULLETIN JULY, 2016 | PAGE 2 LAGOS WORKSHOP MAJLIS ADVOCATES OFFERING SUBJECTS ON AHMADIYYA IN SCHOOLS Majlis Khuddam-ul-Ahmadiyya, Lagos State has urged the schools owned by Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at or its auxiliaries to devise a mechanism allowing students/pupils offer a subject or course that is strictly about Ahmadiyya and value system. his is one of the resolutions made at the State Officers’ Workshop T held between 8th July and 10th July, 2016 at Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at Headquarters, Ojokoro, Lagos. In a communique issued at the end of the 3-day programme, the Majlis also encouraged all officers at all levels to maintain a permanent focus in their respective departments and work based on the requirements of the guidelines as contained in the MKA Constitution and the MKAN Handbook. Moreso, as the nation is The workshop was attended by a total currently striving to get back to of 77 participants. Participants cut It also agreed that Members of the economic growth and across 9 Dil’at (Districts) of the Majlis Majlis at all levels should come development in the face of the in Lagos. Also in attendance were the together based on their present economic challenges, Naib Sadr, Admin, MKAN, Bro Saheed professional and occupational the Majlis urged the government Aina; Naib Sadr, South-West, Bro A.G. preference and put resources to make qualitative education a Omopariola; other Mulk Officers; together on business ventures major consideration in the National Isha’at Secretary and using the Majlis as a rider to gain journey to economic Coordinator, Muslim Television access to wide opportunities. -

1 Nigeria Research Network

Christians and Christianity in Northern Nigeria Ibrahim, J.; Ehrhardt, D.W.L. Citation Ibrahim, J., & Ehrhardt, D. W. L. (2012). Christians and Christianity in Northern Nigeria. Oxford: Nigeria Research Network. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/139167 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/139167 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Nigeria Research Network (NRN) Oxford Department of International Development Queen Elizabeth House University of Oxford NRN WORKING PAPER NO. 12 Christians and Christianity in Northern Nigeria Dr Jibrin Ibrahim, Executive Director, Centre for Democracy & Development, Abuja. & Dr David Ehrhardt, Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford. 2012 Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Islam Research Programme - Abuja, funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The views presented in this paper represent those of the authors and are in no way attributable to the Ministry. 1 Abstract Christians constitute a significant minority in northern Nigeria. This report introduces some of the main dynamics that characterize the contemporary Christian population of Nigeria, with a focus on Christianity in northern Nigeria. It sketches the origins of the divide between ‘old’ and ‘new’ Christian movements and presents data on the demographics and diversity of Nigerian Christianity, suggesting that there are five main Christian movements in Nigeria: the Roman Catholics, the ‘orthodox’ Protestants, the African Protestants, the Aladura churches, and finally the Pentecostals. Furthermore, the paper discusses some of the ways in which Nigerian Christians are positioning themselves and their religion in Nigeria’s public sphere. -

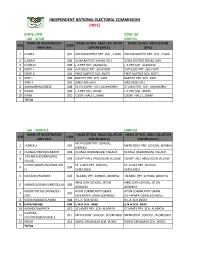

State: Oyo Code: 30 Lga : Afijio Code: 01 Name of Registration Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: OYO CODE: 30 LGA : AFIJIO CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ILORA I 001 OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA 2 ILORA II 002 ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. 3 ILORA III 003 L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. 4 FIDITI I 004 CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI 5 FIDITI II 005 FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI 6 AWE I 006 BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE 7 AWE II 007 AWE HIGH SCH. AWE HIGH SCH. 8 AKINMORIN/JOBELE 008 ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN 9 IWARE 009 L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. 10 IMINI 010 COURT HALL 1, IMINI COURT HALL 1, IMINI TOTAL LGA : AKINYELE CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) CENTRE (RACC) METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, 1 IKEREKU 001 METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, IKEREKU IKEREKU 2 OLANLA/OBODA/LABODE 002 OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE EOLANLA (OGBANGAN) 3 003 COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE VILLAG OLODE/AMOSUN/ONIDUND ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, 4 004 U ONIDUNDU ONIDUNDU 5 OJO-EMO/MONIYA 005 ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN 6 AKINYELE/ISABIYI/IREPODUN 006 AGBAKIN AGBAKIN IWOKOTO/TALONTAN/IDI- AYUN COMMUNITY GRAM. -

Bulletin 2015 National Officers' Workshop Held At

A MONTHLY NEWSLETTERAL-IRFAN OF MAJLIS KHUDDAM-UL-AHMADIYYA NIGERIA BULLETIN EM C BE E R 2015 NATIONAL OFFICERS’ D WORKSHOP HELD AT JAMIA 2015 I S S : 3 AHMADIYYA, ILARO, OGUN STATE U E N O REPORTS FROM SADR’S OFFICE AMSA 1 Sadr’s Trip to South-Africa. 4 Transition to a new executive MAJLIS STORIES CHILDREN’S CORNER News from Ilaqas and Dilas. Happenings around Drawing Challenge 2 the country 5 JAMA’AT NEWS News from the worldwide Ahmadiyya 3 community. AL-IRFAN BULLETIN Volume: 2 Issue: 8 DECEMBER 2015 MKAN URGED TO IMPLEMENT SCHEME OF WORK Owing to low level of interest and zeal towards learning among youths, Majlis Khuddam-ul-Ahmadiyya, Nigeria has been urged to sincerely adopt and implement the Majlis’ scheme of work contained in the Brochure at its various local, district and state levels. his plea is contained to ignorance and illiteracy, in the Communique the communique issued by the encouraged members Organization at the to adopt programmes end of a 3-day National as a means of Officers’T Workshop held at propagating Islam, Jamia Ahmadiyya, Ilaro, Ogun adding that youths State between 25th and 27th cannot progress December, 2015 with the theme intellectually “Training the Officers for Optimum without developing Preformance”. constant reading The programme, declared open culture. by the Sadr, MKAN, Bro Abdur It also mobilized full Rafi’ Abdul Qadir, witnessed moral, financial and 291 participants across six spiritual supports of Southwestern states. Topics members for Ahmadi treated include “Roles of Members Youths All African Games towards AYAAG Programmes, (AYAAG), where more than 25 “Health Talk on Preventive countries are invited, holding in Healthcare”, “Officers’ Trainings February and March for successful on Majlis’ Scheme of Work and hosting.