Nation and Diaspora As Opposing Concepts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sujin Huggins.Pdf

HOW DID WE GET HERE?: AN EXAMINATION OF THE COLLECTION OF CONTEMPORARY CARIBBEAN JUVENILE LITERATURE IN THE CHILDREN’S LIBRARY OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF TRINIDAD & TOBAGO AND TRINIDADIAN CHILDREN’S RESPONSES TO SELECTED TITLES BY SUJIN HUGGINS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Library and Information Science in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christine Jenkins, Chair and Director of Research Professor Violet Harris Professor Linda Smith Assistant Lecturer Louis Regis, University of the West Indies, St. Augustine ABSTRACT This study investigates the West Indian Juvenile collection of Caribbean children's literature housed at the Port of Spain Children's Library of the National Library of Trinidad and Tobago to determine its characteristics and contents, and to elicit the responses of a group of children, aged 11 to 13, to selected works from the collection. A variety of qualitative data collection techniques were employed including document analysis, direct observation, interviews with staff, and focus group discussions with student participants. Through collection analysis, ethnographic content analysis and interview analysis, patterns in the literature and the responses received were extracted in an effort to construct and offer a 'holistic' view of the state of the literature and its influence, and suggest clear implications for its future development and use with children in and out of libraries throughout the region. ii For my grandmother Earline DuFour-Herbert (1917-2007), my eternal inspiration, and my daughter, Jasmine, my constant motivation. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To adequately thank all of the wonderful people who have made the successful completion of this dissertation possible would require another dissertation-length document. -

JM Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston

1 'Presences of the Infinite': J. M. Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston PhD Royal Holloway University of London 2 Declaration of Authorship I, Peter Johnston, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Dated: 3 Abstract This thesis articulates the resonances between J. M. Coetzee's lifelong engagement with mathematics and his practice as a novelist, critic, and poet. Though the critical discourse surrounding Coetzee's literary work continues to flourish, and though the basic details of his background in mathematics are now widely acknowledged, his inheritance from that background has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive and mathematically- literate account. In providing such an account, I propose that these two strands of his intellectual trajectory not only developed in parallel, but together engendered several of the characteristic qualities of his finest work. The structure of the thesis is essentially thematic, but is also broadly chronological. Chapter 1 focuses on Coetzee's poetry, charting the increasing involvement of mathematical concepts and methods in his practice and poetics between 1958 and 1979. Chapter 2 situates his master's thesis alongside archival materials from the early stages of his academic career, and thus traces the development of his philosophical interest in the migration of quantificatory metaphors into other conceptual domains. Concentrating on his doctoral thesis and a series of contemporaneous reviews, essays, and lecture notes, Chapter 3 details the calculated ambivalence with which he therein articulates, adopts, and challenges various statistical methods designed to disclose objective truth. -

Caribbean Voices Broadcasts

APPENDIX © The Author(s) 2016 171 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE BBC CARIBBEAN VOICES BROADCASTS March 11th 1943 to September 7th 1958 © The Author(s) 2016 173 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE BBC CARIBBEAN VOICES EDITORS Una Marson April 1940 to December 1945 Mary Treadgold December 1945 to July 1946 Henry Swanzy July 1946 to November 1954 Vidia Naipaul December 1954 to September 1956 Edgar Mittelholzer October 1956 to September 1958 © The Author(s) 2016 175 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE WEST INDIES FEDERATION AND THE TERRITORIES INCLUDED January 3 1958 to 31 May 31 1962 Antigua & Barbuda Barbados Dominica Grenada Jamaica Montserrat St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla St. Lucia St. Vincent and the Grenadines Trinidad and Tobago © The Author(s) 2016 177 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 CARIBBEAN VOICES : INDEX OF AUTHORS AND SEQUENCE OF BROADCASTS Author Title Broadcast sequence Aarons, A.L.C. The Cow That Laughed 1369 The Dancer 43 Hurricane 14 Madam 67 Mrs. Arroway’s Joe 1 Policeman Tying His Laces 156 Rain 364 Santander Avenue 245 Ablack, Kenneth The Last Two Months 1029 Adams, Clem The Seeker 320 Adams, Robert Harold Arundel Moody 111 Albert, Nelly My World 496 Alleyne, Albert The Last Mule 1089 The Rock Blaster 1275 The Sign of God 1025 Alleyne, Cynthia Travelogue 1329 Allfrey, Phyllis Shand Andersen’s Mermaid 1134 Anderson, Vernon F. -

Society for Caribbean Studies 42Nd Annual Conference Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, University of London, 4-6 July, 2018 Programme

Society for Caribbean Studies 42nd Annual Conference Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, University of London, 4-6 July, 2018 Programme Wednesday 4th July Room Lecture theatre L101 L102 Registration outside the lecture theatre from 11am Please note that no lunch is provided on this day 12.30-1.30 Chair’s welcome and Keynote Presentation: Professor Bill Schwarz, Queen Mary University of London. Title: TBA 1.30 Tea and Coffee Break L03/04 2.00-4.00 Visual translations: art, (Geo)politics Feeling and family: film and writing love, care, passion and policy 4.00 Tea and Coffee Break L03/04 4.30–6.30 Surveying Caribbean Conflicting Memories: The Eastern Caribbean: Outposts, 1924 to 1943 Cross-border Religion, Diaspora, and displacements, and the Archive climate change 6.30 Bridget Jones Award Presentation - Katie Numi Usher 7.30 Buffet Dinner: Chancellors Hall Thursday 5th July Room Lecture theatre L101 L102 9.00–11.00 Writing history Re-reading writers: Changing responses to differently: writing juxtapositions and climate change different histories 1 relocations 11.00 Tea and Coffee Break L03/04 11.30–1.00 Ideologies of race in Circulating forms: Money, business and Cuba print, folk, literature economics 1.00 Lunch L03/04 2.00–3.30 Sonic cultures Caribbean literature in Landscapes of the classroom language and discourse 3.30 Tea and Coffee Break L03/04 4.00-5.30 Carnival cultures Writing history differently: writing different histories 2 5.30-6.30 AGM 6.30–7.30 Rum Punch Reception, including a short presentation by Dr Elizabeth Cooper, Curator of the British Library’s Latin American and Caribbean collections, about the British Library’s exhibition ‘Windrush: Songs in a Strange Land’; and a poetry performance by Keith Jarrett. -

From African to African American: the Creolization of African Culture

From African to African American: The Creolization of African Culture Melvin A. Obey Community Services So long So far away Is Africa Not even memories alive Save those that songs Beat back into the blood... Beat out of blood with words sad-sung In strange un-Negro tongue So long So far away Is Africa -Langston Hughes, Free in a White Society INTRODUCTION When I started working in HISD’s Community Services my first assignment was working with inner city students that came to us straight from TYC (Texas Youth Commission). Many of these young secondary students had committed serious crimes, but at that time they were not treated as adults in the courts. Teaching these young students was a rewarding and enriching experience. You really had to be up close and personal with these students when dealing with emotional problems that would arise each day. Problems of anguish, sadness, low self-esteem, disappointment, loneliness, and of not being wanted or loved, were always present. The teacher had to administer to all of these needs, and in so doing got to know and understand the students. Each personality had to be addressed individually. Many of these students came from one parent homes, where the parent had to work and the student went unsupervised most of the time. In many instances, students were the victims of circumstances beyond their control, the problems of their homes and communities spilled over into academics. The teachers have to do all they can to advise and console, without getting involved to the extent that they lose their effectiveness. -

Conference Schedule

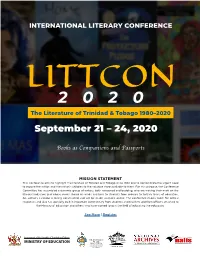

INTERNATIONAL LITERARY CONFERENCE LITTCON2020 The Literature of Trinidad & Tobago 1980–2020 September 21 – 24, 2020 Books as Companions and Passports MISSION STATEMENT This Conference aims to highlight the literature of Trinidad and Tobago since 1980 and to demonstrate the urgent need to expose the nation and the nation’s children to the valuable store available to them. For this purpose, the Conference Committee has assembled a dynamic group of writers, both renowned and budding, who are making their mark on the literary landscape and whose works should be made available to students from primary to tertiary levels of education. An author’s calendar is being constructed and will be made available online. The conference makes room for critical responses and also has specially built in important commentary from students and teachers and from officers attached to the Ministry of Education and others who have worked long in the field of educating the educators. See More | Register THE UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES ST. AUGUSTINE CAMPUS TRINIDAD & TOBAGO WEST INDIES International Literary Conference CALENDAR OF EVENTS: MONDAY 21ST SEPTEMBER, 2020 INTRODUCTION TO THE LITERARY LANDSCAPE OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Day Chair: Dr. J. Vijay Maharaj 8:00am - 8:45 am OPENING THE FRONTIERS Moderator: Dr. J. Vijay Maharaj Welcome, HOD DLCCS: Professor Paula Morgan Greetings by the Principal UWI STA: The Humanities in the 21st Century- Professor Brian Copeland Remarks from the Chairman, Friends of Mr Biswas The Conference: Structure and Purpose – Professor Kenneth Ramchand Feature Address by the Minister of Education: Dr the Honourable Nyan Gadsby-Dolly 8:45am – 9:45am THE HEART OF THE MATTER Moderator: Professor Kenneth Ramchand Presentation of the Annotated Bibliography: Ms. -

About the Author

Lawrence Hill: About the Author Hill is the author of ten books of fiction and non-fiction. In 2005, he won his first Writing literary honour: a National Magazine Award for the article “Is Africa’s Pain Black America’s Burden?” published in The Walrus. His first two novels were Some Great Thing and Any Known Blood, and his first non-fiction work to attract national attention was the memoir Black Berry, Sweet Juice: On Being Black and White in Canada. But it was his third novel, The Book of Negroes (HarperCollins Canada, 2007) — published in some countries as Someone Knows My Name and in French as Aminata — that attracted widespread attention in Canada and other countries. Lawrence Hill’s non-fiction book, Blood: The Stuff of Life was published in September 2013 by House of Anansi Press. Blood is a personal consideration of the physical, social, cultural and psychological aspects of blood, and how it defines, unites and divides us. Hill drew from the book to deliver the 2013 Massey Lectures across Canada. In 2013, Hill published the essay Dear Sir, I Intend to Burn Your Book: An Anatomy of a Book Burning (University of Alberta Press). His fourth novel, The Illegal, was published by HarperCollins Canada in 2015 and by WW Norton in the USA in 2016. Hill is currently writing a new novel and a children’s book, and is a professor of creative writing at the University of Guelph, in Ontario. Personal Lawrence Hill is the son of American immigrants — a black father and a white mother — who came to Canada the day after they married in 1953 in Washington, D.C. -

MS Coll 00761

Ms. Lawrence Hill papers Coll. 761 Gift of Lawrence Hill 2015 Includes drafts, research, correspondence and other material related to The Book of Negroes, including the screenplay for the televised series and the illustrated edition; interviews for Black Berry, Sweet Juice; notes, drafts, proofs, copy-editing and other material for The Illegal (early title ‘Underground’) forthcoming novel Fall 2015 (fourth novel and tenth book); personal and professional correspondence; appearances; extended family material; awards; photographs; notebooks; community activities; short pieces, including ‘Africville Forever’; Karen Hill’s Café Babanussa; research, various drafts, proofs and appearance material related to The Massey lectures: Blood: the Stuff of Life; The Deserter’s Tale; and other material related to the life, work and family of Lawrence Hill. Extent: 101 boxes and items (23 metres) The Illegal (early title ‘Underground’) Boxes 1-24 The Book of Negroes Boxes 36-45 Black Berry, Sweet Juice Box 35 Blood: the Stuff of Life Massey Lectures Boxes 27-34 The Deserter’s Tale Boxes 25-26 Correspondence, personal and professional Boxes 88-95 Speeches, Appearances, Honours and Awards Boxes 57-84 Personal/Hill family Boxes 55-56 Karen Hill, Café Babanussa Box 46 Short pieces/other writing/various Boxes 47-54 Holograph notebooks Boxes 85-87 Miscellaneous Boxes 96-101 1 Ms. Lawrence Hill papers Coll. 761 Box 1 The Illegal 23 folders Early drafts and notes, 2008-2011, including songs Folder 1 Songs for use in The Illegal Folders 2-3 The Illegal Character -

Localization and the Chinese Overseas: Acculturation, Assimilation, Hybridization, Creolization, and Identification

Cultural and Religious Studies, February 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, 73-87 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2018.02.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Localization and the Chinese Overseas: Acculturation, Assimilation, Hybridization, Creolization, and Identification TAN Chee-Beng Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China Based on materials on the localized Chinese overseas, including the Melaka Babas, who are mostly Malay-speaking Chinese, this article reflects on the use of such terms as acculturation and assimilation, as well as hybridization and creolization, in relation to highly localized Chinese. All these concepts are seen as different ways of describing cultural formation in transcultural context. In particular, the relevance of using creolization to refer to the kind of creative process of cultural formation beyond its original usage in the Caribbean is discussed. This results in the identification of fragmented creolization as in the case of the Caribbean and a rooted creolization as in the case of the Babas. The author shall first discuss the issues of assimilation and integration, followed by hybridization and creolization. This is followed by the discussion on localization of Chinese overseas and identity. The concluding section provides some remarks on the concepts reviewed, and three main categories of acculturated Chinese are identified, namely, Chinese who are linguistically assimilated but still observe major Chinese traditions, Chinese who are so acculturated to the mainstream society that they hardly practice Chinese traditions, and Chinese who are both highly localized and highly mixed “racially”. Keywords: acculturation and assimilation, hybridization, creolization, localization and identity, Baba, Chinese overseas Introduction1 A noticeable feature of Chinese overseas is their local cultural adaptation. -

J. Dillon Brown One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1122 St

J. Dillon Brown One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1122 St. Louis, MO 63130 (314) 935-9241 [email protected] Appointments 2014-present Associate Professor of Anglophone Literatures Department of English, African and African American Studies Program Washington University in St. Louis 2007-2014 Assistant Professor of Anglophone Literatures Department of English, African and African American Studies Program Washington University in St. Louis 2006-2007 Assistant Professor of Diaspora Studies English Department Brooklyn College, City University of New York Education 2006 Ph.D. in English Literature, University of Pennsylvania 1994 B.A. in English Literature, University of California, Berkeley Fellowships, Grants, Awards Summer 2013 Arts and Sciences Research Seed Grant (Washington University) Spring 2013 Center for the Humanities Faculty Fellowship (Washington University) 2011 Common Ground Course Development Grant (Washington University) 2009 Harry S. Ransom Center British Studies Fellowship 2009 Special Recognition for Excellence in Graduate Student Mentoring Summer 2007 PSC CUNY Research Award 2006-2007 Brooklyn College New Faculty Fund Award 2006-2007 Leonard & Clare Tow Faculty Travel Fellowship (Brooklyn College) 2004-2005 J. William Fulbright Research Grant (for Barbados and Trinidad & Tobago) Books Migrant Modernism: Postwar London and the West Indian Novel Monograph examining the metropolitan origins of early West Indian novels with an interest in establishing the historical, social, and cultural contexts of their production. Through individual case studies of George Lamming, Roger Mais, Edgar Mittelholzer, V.S. Naipaul, and Samuel Selvon, the book seeks to demonstrate Caribbean fiction’s important engagements with the experimental tradition of British modernism and discuss the implications of such engagements in terms of understanding the nature, history, locations, and legacies of both modernist and postcolonial literature. -

Annual Report 2015–2016

THE NATIONAL HUMANITIES CENTER ANNUAL REPORT 2015-2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 Report from the President and Director 8 Scholarly Programs Work of the Fellows Statistics Books by Fellows 30 Education Programs 32 Public Engagement 34 Highlights of the Year 36 Financial Statements 38 Supporting the Center Center Supporters The National Humanities Center does Annual Giving Summary not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, gender identity, religion, national and ethnic origin, sexual orientation or preference, or age in the administration 44 Staff of the Center of its selection policies, educational policies, and other Center-administered programs. 45 Board of Trustees Editor Donald Solomon Images Joel Elliott Design Barbara Schneider The National Humanities Center’s Report (ISSN 1040-130X) is printed on recycled paper. Copyright ©2016 by National Humanities Center 7 T.W. Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256, RTP, NC 27709-2256 Tel 919-549-0661 Fax 919-990-8535 Email: [email protected] Website: nationalhumanitiescenter.org The humanities encourage a culture of rigor, pluralism, innovation, and evidence. As long as these values are maintained in our processes and products, the shape our work takes, the audiences it reaches, and the valuation it receives benefit from a healthy multiplicity and a resistance to static definitions and one-dimensional accountability. – Robert D. Newman REPORT FROM THE PRESIDENT & DIRECTOR When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer When I heard the learn’d astronomer, When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me, When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them, When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room, How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick, Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself, In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time, Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars. -

Calypso Overseas and the Sound of Belonging in Selected Narratives of Migration Jennifer Rahim [email protected]

Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal Volume 3 Issue 2 Calypso and the Caribbean Literary Article 12 Imagination: A Special Issue December 2005 (Not) Knowing the Difference: Calypso Overseas and the Sound of Belonging in Selected Narratives of Migration Jennifer Rahim [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium Recommended Citation Rahim, Jennifer (2005) "(Not) Knowing the Difference: Calypso Overseas and the Sound of Belonging in Selected Narratives of Migration," Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2 , Article 12. Available at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium/vol3/iss2/12 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rahim: (Not) Knowing the Difference: Calypso Overseas and the Sound... Culture is an embodied phenomenon. This implies that one’s cultural location is not fixed to any one geographical space. Cultures, in other words, are not inherently provincial by nature. They move and evolve with the bodies that create and live them. The Caribbean civilization understands the logic of traveling cultures given that the dual forces of rooted-ness and itinerancy shape its diasporic ethos. Travel is how we “do” culture. Indeed, the Caribbean’s literary tradition is marked by a preoccupation with identity constructs that display allegiances to particular island locations and nationalisms, on the one hand, and transnational sensibilities that are regional and metropolitan on the other. This paper is interested in the function of the calypso as a sign of cultural identity and belonging in selected narratives that focus on the experiences of West Indian immigrants to the metropolitan centers of England and the United States.