Always the Feminine Fool

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Dolorologies

American Dolorologies Item Type Book Authors Strick, Simon DOI 10.1353/book.28834 Publisher SUNY Press Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 29/09/2021 04:15:19 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item https://www.sunypress.edu/p-5822-american-dolorologies.aspx AMERICAN DOLOROLOGIES AMERICAN DOLOROLOGIES Pain, Sentimentalism, Biopolitics SIMON STRICK State University of New York Press Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2014 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production, Laurie Searl Marketing, Anne M. Valentine Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Strick, Simon, 1974– American dolorologies : pain, sentimentalism, biopolitics / Simon Strick. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4384-5021-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Pain—Social aspects—United States. 2. Suffering—Social aspects—United States. 3. United States—Civilization. 4. Sentimentalism. I. Title. BJ1409.S85 2014 306.4—dc23 2013014434 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix CHAPTER ONE What Is Dolorology? 1 CHAPTER TWO Sublime Pain and the Subject of Sentimentalism 19 CHAPTER THREE Anesthesia, Birthpain, and Civilization 51 CHAPTER FOUR Picturing Racial Pain 93 CHAPTER FIVE Late Modern Pain 147 NOTES 169 WORKS CITED 199 INDEX 219 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 4.1 gordon: The Scourged Back/Escaped slave displays wounds from torture. -

Marlpit 2010.07

THE MARLPIT July 2010 VVillage DiarD ry Juuly 2010 Saturrday 3rd 11.00 - 2.00 Horninng Communiity Primary SSchool and HedgehogsH Pre-school, Summeru Fair Saturrday 3rd 1.00 - 4.00 Tunsteead School SSummer Fayrre, Tunstead Primary Schhool, Market Street, Tunsstead Mondday 5th 7.30pm Coltishhall Parish CCouncil Meetting, Village Hall Wednnesday 7th 7.30pm The Elleventh Mikee Groves Ruun, Start Foottball Field, RRectory Roadd Saturrday 10th 10.00 - 4.00 Girl GGuides Leadinng the Way, Wroxham Scarecrow Coonvention froom Wroxhamm Sundday 11th Churchh Hall Wednnesday 14th 7.30pm Horsteead with Stannninghall Parrish Council, Hayloft, Tiithe Barn, Hoorstead Saturrday 17th 7.00 - 10.00 Traditional Jazz Band Concert, The Museuum of The Brroads Sundday 18th 11.00 - 4.00 1st Hovveton and WWroxham Sea Scout Groupp, 7th Annuall Classic Car Show Wednnesday 21th 7.00pm Womeen’s Institutee, Meeting, VillageV Hall, Coltishall Sundday 25th 3.00pm Duck RRace, From HorsteadH Miill to Horsteaad House Saturrday 31st Coltishhall Fete Auggust 20102 Tuesdday 10th 10.00 - 12.00 Centraal Norfolk Health Walk from Coltishall, from Colltishall Villagge Hall Car Park Saturrday 14th 2.30pm The MMill House Nuursing Homee, Garden Paarty The Marlpitt aims to produce a magaazine as an innformative coommunicatioon of local neews, events and articles. AArticles are ppublished inn good faith aand are not necessarilyn thhe opinion off the Editors. Anyy item submitted must haave a contactt name and teelephone nummber for usee by the Editoors. Noon-Commerccial Advertissements for VVillage Evennts, Interests and Activitiees are free off charge for oone issue onlly. They will oonly be acceppted if they fit a maximum of a ½ pagge and will be re-sized at the Editors’ discretion. -

1998 Fellows Thesis S62.Pdf (2.156Mb)

MADNESS, THE SUPERNA TUBAL A1VD THE UNRELIABLE NARRA TOR IN GUYDE MA UPASSA1VT'S LE HORLA AND HENRY JAMES'S THE TURN OF THE SCREiW A Senior Thesis By Janna Smartt 1997-98 University Undergraduate Research Fellow Texas A@M University Group: Humanities Madness, the Supernatural and the Unreliable Narrator in Guy de Maupassant's Le Horla and Henry James's The Turn of the Screw by Janus Smartt Submitted to the Office of Honors Programs and Acadetnic Scholarships Texas AdcM University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for 1997-98 UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH FELLOWS PROGRAM April 16, 1998 Approved as to style and content by: David McWhirter Department of English Susanna Finnell, Executive Director Honors Programs and Academic Scholarships Fellows Group: Humanities Abstract Madness, the Supernatural, and the Unreliable Narrator Janna S martt (Dr. David McWhirter), Undergraduate Fellow, 1997-98, Texas AdkM University, Department of English In both Guy de Maupassant' s Le Horla and Henry James' s The Turn of the Screw, narrators of questionable reliability claim to encounter other-worldly beings, leaving the reader to wonder whether the apparitions are real or the narrators are insane. This madness/supernatural conundrum recurs because of certain trends within the writers' cultural and literary milieux. From a literary standpoint, both Maupassant and James were working in the fanrastique, a genre which, by definition, indicates that the reader hesitates between natural and supernatural explanations for the story's events. And, from a cultural perspective, both writers were writing in environments where the distinction between spiritualism and psychology was often unclear. Maupassant leaves his reader in hesitation as a way of expressing the cultural ambiguity between madness and the supernatural, whereas James utilizes the blur between madness and the supernatural to explore the "reading effect" that the reader experiences when left in hesitation. -

Official Journal of the European Communities

ISSN 0378-liiM1 Annex Official Journal of the European Communities No 234 October 1978 English edition Debates of the European Parliament 1978-1979 Session Report of Proceedings from 9 to 13 October 197 8 Europe House, Strasbourg Contents Sitting of Monday, 9 October 1978 Resumption, p. 2 - Death of John Paul I, p. 2 - Committees, p. 2 - Petitions, p. 2 - Documents, p. 2 - Texts of treaties, p. 5 - Authorization of reports, p. 5 - Urgent procedure, p. 5 - Urgent procedure (decision~ p. 6 - Order of business, p. 6 - Limitation of speaking-time, p. 10 - Procedure without report, p. 10 - Amendments, p. 11 - Action taken on the opinions of Parliament, p. 11 - Community VAT, p. 12- Implementation of the 1978 budget, p. 16- Amend ments to the Financial Regulation, p. 25 - Floods in Northern Italy, p. 27 - Next sitting, p. 29. Sitting of Tuesday, 10 October 1978 30 Minutes, p. 32 - Documents, p. 32 - Transfers of appropriations, p. 32 - Urgent procedure, p. 32 - Illegal migration, p. 37 - Question Time, p. 52 - Votes, p. 60 -Equal treatment for men and women, p. 65- 1978 Tripartite Conference, p. 74 - Agenda, p. 78 - 1978 Tripartite Conference (resumption), p. 79 - Agricultural research programmes, p. 90 - Approximation of legislation, p. 98 - Price of milk products, p. 104 - Massacre of seals, p. 110 - Next sitting, p. 113. Sitting of Wednesday, 11 October 1978 114 Minutes, p. 116 - Documents, p. 116 - Texts of treaties, p. 116 - Agenda, p. 116 - Supplies of armaments, p. 117 - Summer-time, p. 125 - Camp David Conference, p. 129- Urgent procedure, p. 135- Question Time (continued~ p. -

Emma Willis Emma

Midlands Cover - Sept_Layout 1 27/08/2013 19:46 Page 1 MIDLANDS WHAT’S ON WHAT’S MIDLANDS THE MIDLANDS ESSENTIAL ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE ISSUE 333 SEPTEMBER 2013 SEPTEMBER www.whatsonlive.co.uk £1.80 ISSUE 333 SEPTEMBER 2013 4 SQUARES WEEKENDER EIGHTEEN-PAGE GUIDE INSIDE THE DEFINITIVE LISTINGS GUIDE INSIDE: INCLUDING BIRMINGHAM Welcome Home! WOLVERHAMPTON WALSALL The REP’s back in DUDLEY COVENTRY Centenary Square STRATFORD WORCESTER feature inside REDDITCH MALVERN SHREWSBURY TELFORD Mark Ravenhill STAFFORD STOKE brings Voltaire’s Candide to the RSC interview inside The Show:Ten Mollie King at Bullring more inside PART OF MIDLANDS WHAT’S ON MAGAZINE GROUP PUBLICATIONS GROUP MAGAZINE ON WHAT’S MIDLANDS OF PART What’sOn Emma Willis MAGAZINE GROUP showing off her Style... feature inside ISSN 2053 - 3128 - 2053 ISSN (IBC) R1_Layout 1 27/08/2013 13:59 Page 1 Contents September_Layout 1 27/08/2013 19:05 Page 1 September 2013 Editor: INSIDE: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 Editorial Assistants: People Brian O’Faolain Alan Bennett play shows [email protected] 01743 281707 at The REP p31 Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Sales & Marketing: Jon Cartwright [email protected] 01743 281703 Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 Subscriptions: Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Managing Director: Paul Oliver [email protected] 01743 281711 Publisher and CEO: Martin Monahan [email protected] 01743 281710 Graphic Designers: Lisa Wassell Chris Atherton -

15Aprhoddercat Autumn21 FO

FICTION 3 CRIME & THRILLERS 35 NON-FICTION 65 CORONET 91 HODDER STUDIO 99 YELLOW KITE & LIFESTYLE 117 sales information 136 FICTION N @hodderbooks M HodderBooks [ @hodderbooks July 2021 Romantic Comedy . Contemporary . Holiday WELCOME TO FERRY LANE MARKET Ferry Lane Market Book 1 Nicola May Internationally bestselling phenomenon Nicola May is back with a brand new series. Thirty-three-year-old Kara Moon has worked on the market’s flower stall ever since leaving school, dreaming of bigger things. When her good-for-nothing boyfriend cheats on her and steals her life savings, she finally dumps him and rents out her spare room as an Airbnb. Then an anonymous postcard arrives, along with a plane ticket to New York. And there begins the first of three trips of a lifetime, during which she will learn important lessons about herself, her life and what she wants from it – and perhaps find love along the way. Nicola May is a rom-com superstar. She is the author of a dozen novels, all of which have appeared in the Kindle bestseller charts. The Corner Shop in Cockleberry Bay spent 11 weeks at the top of the Kindle bestseller chart and was the overall best-selling fiction ebook of 2019 across the whole UK market. Her books have been translated into 12 languages. 9781529346442 • £7.99 Exclusive territories: Publicity contact: Rebecca Mundy B format Paperback • 384pp World English Language Advance book proofs available on request eBook: 9781529346459 • £7.99 US Rights: Hodder & Stoughton Author lives in Ascot, Berkshire. Author Audio download: Translation Rights: is available for: interview, features, 9781529346466 • £19.99 Lorella Belli, LBLA festival appearances, local events. -

ULTIMATE PORSCHE 40 Kelsey Media, Cudham Tithe Barn, YEARS of the Berry’S Hill, Cudham, Kent TN16 3AG

NEW WICKY 911 250BHP RALLY ROCKET RIDES AGAIN PorsUltimate e 100% CLASSIC PORSCHES ISSUE No 1 MAY 2017 £4.95 25pages DEDICATED TO A V8 ICON INCLUDING ● MODEL HISTORY ● S2 BUYING GUIDE ● GTS DRIVEN years of 928 PLUS 40 NEEL JANI The last RHD RS 2.7 The hide in your ride FIA WEC champ on his ‘Trinidad’ gets ready for a rebuild Our guide to restoring cabin leather love of Porsche London’s only Porsche Recommended Repair Centre Established in 1971, specialising in Prestige Body Repairs and restoration. A reputation built on quality, fine detail and integrity. London’s only recommended Porsche Repair Centre. Officially approved, recommended and trusted by the leading motor manufacturers of the world. M&A Coachworks. 135 Highgate Road London NW5 1LE Call 0203 823 1900 Email [email protected] www.macoachworks.co.uk WELCOME / ULTIMATE PORSCHE 40 Kelsey Media, Cudham Tithe Barn, YEARS OF THE Berry’s Hill, Cudham, Kent TN16 3AG EDITORIAL Editor: Dan Furr Twitter: @DanFurr Email: [email protected] Art Editor: Hallam Foster Contributors: Matt Woods, Alan Schaefer, Sharon Horsley, Ben Richards, Eros Gosub, CELEBRATION Paul Lacey, John Matrix, Ray Owens ISSUE ADVERTISEMENT SALES TANDEM MEDIA Managing Director: Catherine Rowe [email protected] Account Managers: Emma Philcox, 01233 228751 [email protected] Ben Rayment, 01233 228752 [email protected] Perianne Smith, 01233 228753 [email protected] PRODUCTION Production supervisor: Joe Harris, 01733 362318 [email protected] Production -

The Ultimate Madness of the Trans-Atlantic Speculative Bubble by Stephanie Ezrol

BITCOIN: A PERSPECTIVE FROM FRANCE The Ultimate Madness of the Trans-Atlantic Speculative Bubble by Stephanie Ezrol The following report is It’s only the most ex- adapted from an article treme aspect of the whole posted Dec. 21, 2017 on the Ponzi scheme of the finan- French-language website cial and monetarist system Solidarité et Progrès, and of the West that goes back to from other Europe-based the 1971 break-up of FDR’s discussions which included Bretton Woods agreements, former French presidential which break-up was a result candidate Jacques Chemi- of America’s post-FDR col- nade, EIR founder Lyndon laboration with the British H. LaRouche, Jr., and Schil- empire speculators and fi- ler Institute President Helga nancial predators initiated by Zepp-LaRouche, on the sub- President Truman—a collab- ject of the Bitcoin bubble. oration Lyndon LaRouche had warned would lead to Dec. 25—The story has unprecedented disaster. often been told that in 1929 a This bubble is proof for rich bootlegger, Joseph Ken- people who still are willing nedy (father of the future to think, of how this system president of the United is becoming absolutely States) was having his shoes insane. The new paradigm, shined by his usual shoe- for which Helga Zepp-La- shine guy. At one point, the Rouche has become a major guy looked up at him and international spokesperson said, “Mr. Kennedy, I’ve got and leader, is something a super stock tip for you.” more than just the new rail- Kennedy listened, but immediately concluded that if roads and other impressive infrastructure of China’s shoe-shine men were now speculating on the market, it New Silk Road. -

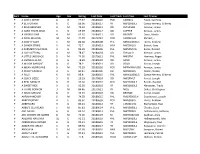

Gait Horse Age Sex Rating Last Date Last Track Last Class Last Trainer

Gait Horse Age Sex Rating Last Date Last Track Last Class Last Trainer P A AND C ARTIST 8 G 77.37 20180616 PCD 10000CL Fusco, Carmine P A BETTOR HAT 6 G 86.96 20180617 YR NW10000L5 Garcia-Herrera, Gilberto P A BLUE BELIEVER 4 M 70.33 20180611 OD FM SILVER Armour, James P A CARD THATS WILD 5 G 69.39 20180617 OD COPPER Armour, James T A CHORUS LINE 4 M 65.35 20180611 OD BRONZE Davis, Martin T A COOL MILLION 10 M 77.48 20170724 PCD 10000CLHC Ehrhart, J P A CRAFTY LADY 5 M 86.68 20180608 PHL MNW14000L5 Harris, Andrew T A DANDY STRIKE 9 M 72.7 20180613 HAR NW2001L5 Botsch, Gary P A FARMBOYS SUCCESS 4 G 84.28 20180606 PHL NW5PM CG Burke, Ronald P A LADY SIZZLING 4 M 78.67 20180618 OD FM GOLD Armour, James T A LITTLE LAID BACK 5 M 74.05 20170611 PHL NW3PM Hammer, Roger P A LIVING LEGEND 9 G 78.49 20180610 OD GOLD Armour, James P A MAJOR IMPULSE 8 G 78.9 20180611 OD GOLD Karrat, Joseph P A MEAN HURRICANE 9 M 75.29 20180530 RCR MPFMNW4000 Armour, James T A PENNY EARNED 9 G 80.47 20180306 DD NW4001L6 Nason, Steven P A PLUS 6 M 85.8 20180615 PHL MNW10000L5 Garcia-Herrera, Gilberto P A QUICK SIZZLE 5 G 59.23 20170824 OD NW2PMLT Karrat, Joseph P A REAL MIRACLE 8 H 93.94 20180616 PCD NW12000L5 Bendis, Randall P A SWEET RIDE 9 G 92.03 20180310 YR NW20000L5 Alexander, Travis T A THING GOIN ON 3 M 84.46 20170911 YR NYSS Oakes, Christopher P A WILD IMPULSE 8 G 73.15 20180618 OD BRONZE Karrat, Joseph P AARIN HANOVER 6 M 74.58 20180615 PHL FM10000CLH Eisenhower, Joseph P ABBEYDORNEY 4 G 83.62 20180609 PCD NW6500L5 Harris, Andrew P ABBEYLARA 9 G 80.13 20180612 -

AGUIRRE, the WRATH of GOD Werner Herzog

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE Frederic Will, Ph.D. AGUIRRE, THE WRATH OF GOD Werner Herzog. 1942- OVERVIEW The present epic historical film retraces (largely fictionally) the Amazonian journey of the Spanish soldier Lope de Aguirre, in search of the mysterious El Dorado, the Golden City that preoccupied the Spanish conquistadores, as the sixteenth century proved of lucrative world historical importance for the Empire of Spain. There are texts of the time that give partial support, to the narrative Herzog amplifies and reshapes, and all agree that the historical launching point, for the tale before us, is the march (in 1580) of several hundred conquistadores south from the Inca Empire. The group was under the command of Fernando Pizzaro, the redoubtable ‘conqueror’ of Inca Peru and in that sense it is thanks to him that the surviving of mountain floods, high mountain jungles to cross, and angry Indian tribes brought the Aguirre narrative to birth. For at a certain point, deep into the jungle and beginning to wonder whether El Dorado was out there, Pizzaro sent a party of forty men downstream to acquire information about what was ahead of them. (Supplies were running out, the jungle and its dangers were crushing them.) Don Pedro Ursa was sent in command, with Aguirre his second. (Two women were included: Ursa’s mistress, and the teen age daughter of Aguirre.) The agreement was that if the party had not returned in a week, they would be considered lost. There, at what is still history, begins the narrative Herzog created, largely about Aguirre and his ultimate madness. -

China's Creative Industries and Intellectual

Creativity and Its Discontents Creativity and Its Discontents China’s Creative Industries and Intellectual Property Rights Offenses Laikwan Pang Duke University Press Durham and London 2012 © 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ♾ Typeset in Minion and Hypatia Sans by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange, which provided funds toward the production of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 Part I UnderstandIng CreatIvIty 1 Creativity as a Problem of Modernity 29 2 Creativity as a Product of Labor 47 3 Creativity as a Construct of Rights 67 Part II ChIna’s CreatIve IndUstrIes and IPr Offenses 4 Cultural Policy, Intellectual Property Rights, and Cultural Tourism 89 5 Cinema as a Creative Industry 113 6 Branding the Creative City with Fine Arts 133 7 Animation and Transcultural Signification 161 8 A Semiotics of the Counterfeit Product 183 9 Imitation or Appropriation Arts? 203 Notes 231 Bibliography 261 Index 289 Acknowledgments It took me a long time to come up with a page of acknowledgments for my first book. But the list of people I feel obliged to thank grows as my research broadens, and I realize that the older I get, the more people I am indebted to. This is a good feeling. Several scholars have read parts of the manuscript in different stages and offered me their valuable comments and criticisms. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least.