“Cockney and the Queen”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Going the Pub and Being the Library

Going the Pub and Being the Library A Microparameter in North-West English Preposi>onal Phrases Boston University Linguis>cs Faculty Spotlight Thursday, Oct 2nd Neil Myler ([email protected]) The United Kingdom 2 England 3 England The North West of England 4 Bit of the North West we’re dealing with 5 Bit of the North West we’re dealing with Scouse 6 Bit of the North West we’re dealing with Woolyback Scouse 7 Scousers, Plas>c Scousers (Placcies) and Woolybacks St Helens, Widnes etc are wools. Huyton, Kirkby, Bootle etc. are borderline. Birkenhead are the biggest wools. Wools want to be Scousers, Scousers don’t want to be wools. Stevie Dunn I AM proud to be classed as a Scouser and here are my defini>ons. Scouser: An individual born within eyesight of the Liver Building or adopted by the en>re city. Must have a Liverpudlian accent and be proud that we sound Australian to all Americans. Plas>c Scousers: Those born in eyesight of the Liver Building, but have to cross water, or those born and living within the city, but wish to speak differently and live elsewhere. Woolybacks: Those who sound like they live near sheep – areas like Manchester, Warrington and Widnes. Lulla h[p://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/scousers-plas>c-scousers-woolybacks--3366630 h[p://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/nostalgia/what-plas>c-scouser-paddy-shennan-3370855 8 Definite Woolybacks The Lancashire Hotpots • Comedy folk band from St Helens • Named aer “Lancashire Hotpot”, a tradi>onal stew. • Note flatcaps, waistcoats etc. -

Social and Cultural Functions of the Local Press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855-1900

Reading the local paper: Social and cultural functions of the local press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855-1900 by Andrew Hobbs A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire November 2010 ABSTRACT This thesis demonstrates that the most popular periodical genre of the second half of the nineteenth century was the provincial newspaper. Using evidence from news rooms, libraries, the trade press and oral history, it argues that the majority of readers (particularly working-class readers) preferred the local press, because of its faster delivery of news, and because of its local and localised content. Building on the work of Law and Potter, the thesis treats the provincial press as a national network and a national system, a structure which enabled it to offer a more effective news distribution service than metropolitan papers. Taking the town of Preston, Lancashire, as a case study, this thesis provides some background to the most popular local publications of the period, and uses the diaries of Preston journalist Anthony Hewitson as a case study of the career of a local reporter, editor and proprietor. Three examples of how the local press consciously promoted local identity are discussed: Hewitson’s remoulding of the Preston Chronicle, the same paper’s changing treatment of Lancashire dialect, and coverage of professional football. These case studies demonstrate some of the local press content that could not practically be provided by metropolitan publications. The ‘reading world’ of this provincial town is reconstructed, to reveal the historical circumstances in which newspapers and the local paper in particular were read. -

Origins of NZ English

Origins of NZ English There are three basic theories about the origins of New Zealand English, each with minor variants. Although they are usually presented as alternative theories, they are not necessarily incompatible. The theories are: • New Zealand English is a version of 19th century Cockney (lower-class London) speech; • New Zealand English is a version of Australian English; • New Zealand English developed independently from all other varieties from the mixture of accents and dialects that the Anglophone settlers in New Zealand brought with them. New Zealand as Cockney The idea that New Zealand English is Cockney English derives from the perceptions of English people. People not themselves from London hear some of the same pronunciations in New Zealand that they hear from lower-class Londoners. In particular, some of the vowel sounds are similar. So the vowel sound in a word like pat in both lower-class London English and in New Zealand English makes that word sound like pet to other English people. There is a joke in England that sex is what Londoners get their coal in. That is, the London pronunciation of sacks sounds like sex to other English people. The same joke would work with New Zealanders (and also with South Africans and with Australians, until very recently). Similarly, English people from outside London perceive both the London and the New Zealand versions of the word tie to be like their toy. But while there are undoubted similarities between lower-class London English and New Zealand (and South African and Australian) varieties of English, they are by no means identical. -

Standard Southern British English As Referee Design in Irish Radio Advertising

Joan O’Sullivan Standard Southern British English as referee design in Irish radio advertising Abstract: The exploitation of external as opposed to local language varieties in advertising can be associated with a history of colonization, the external variety being viewed as superior to the local (Bell 1991: 145). Although “Standard English” in terms of accent was never an exonormative model for speakers in Ireland (Hickey 2012), nevertheless Ireland’s history of colonization by Britain, together with the geographical proximity and close socio-political and sociocultural connections of the two countries makes the Irish context an interesting one in which to examine this phenomenon. This study looks at how and to what extent standard British Received Pronunciation (RP), now termed Standard Southern British English (SSBE) (see Hughes et al. 2012) as opposed to Irish English varieties is exploited in radio advertising in Ireland. The study is based on a quantitative and qualitative analysis of a corpus of ads broadcast on an Irish radio station in the years 1977, 1987, 1997 and 2007. The use of SSBE in the ads is examined in terms of referee design (Bell 1984) which has been found to be a useful concept in explaining variety choice in the advertising context and in “taking the ideological temperature” of society (Vestergaard and Schroder 1985: 121). The analysis is based on Sussex’s (1989) advertisement components of Action and Comment, which relate to the genre of the discourse. Keywords: advertising, language variety, referee design, language ideology. 1 Introduction The use of language variety in the domain of advertising has received considerable attention during the past two decades (for example, Bell 1991; Lee 1992; Koslow et al. -

LINGUISTIC CONTEXT of H-DROPPING Heinrich RAMISCH University of Bamberg Heinrich

Dialectologia. Special issue, I (2010), 175-184. ISSN: 2013-22477 ANALYSING LINGUISTIC ATLAS DATA: THE (SOCIO-) LINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF H-DROPPING Heinrich R AMISCH University of Bamberg [email protected] Abstract This presentation will seek to illustrate how linguistic atlas data can be employed to obtain a better understanding of the mechanisms of linguistic variation and change. For this purpose, I will take a closer look at ‘H-dropping’ – a feature commonly found in various European languages and also widely used in varieties of British English. H-dropping refers to the non-realization of /h/ in initial position in stressed syllables before vowels, as for example, in hand on heart [ 'ænd ɒn 'ɑː t] or my head [m ɪ 'ɛd]. It is one of the best-known nonstandard features in British English, extremely widespread, but also heavily stigmatised and commonly regarded as ‘uneducated’, ‘sloppy’, ‘lazy’, etc. It prominently appears in descriptions of urban accents in Britain (cf. Foulkes/Docherty 1999) and according to Wells (1982: 254), it is “the single most powerful pronunciation shibboleth in England”. H-dropping has frequently been analysed in sociolinguistic studies of British English and it can indeed be regarded as a typical feature of working-class speech. Moreover, H-dropping is often cited as one of the features that differentiate ‘Estuary English’ from Cockney, with speakers of the former variety avoiding ‘to drop their aitches’. The term ‘Estuary English’ is used as a label for an intermediate variety between the most localised form of London speech (Cockney) and a standard form of pronunciation in the Greater London area. -

Barrow-In-Furness, Cumbria

BBC VOICES RECORDINGS http://sounds.bl.uk Title: Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria Shelfmark: C1190/11/01 Recording date: 2005 Speakers: Airaksinen, Ben, b. 1987 Helsinki; male; sixth-form student (father b. Finland, research scientist; mother b. Barrow-in-Furness) France, Jane, b. 1954 Barrow-in-Furness; female; unemployed (father b. Knotty Ash, shoemaker; mother b. Bootle, housewife) Andy, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; male; sixth-form student (father b. Barrow-in-Furness, shop sales assistant; mother b. Harrow, dinner lady) Clare, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; female; sixth-form student (father b. Barrow-in-Furness, farmer; mother b. Brentwood, Essex) Lucy, b. 1988 Leeds; female; sixth-form student (father b. Pudsey, farmer; mother b. Dewsbury, building and construction tutor; nursing home activities co-ordinator) Nathan, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; male; sixth-form student (father b. Dalton-in-Furness, IT worker; mother b. Barrow-in-Furness) The interviewees (except Jane France) are sixth-form students at Barrow VI Form College. ELICITED LEXIS ○ see English Dialect Dictionary (1898-1905) ∆ see New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (2006) ◊ see Green’s Dictionary of Slang (2010) ♥ see Dictionary of Contemporary Slang (2014) ♦ see Urban Dictionary (online) ⌂ no previous source (with this sense) identified pleased chuffed; happy; made-up tired knackered unwell ill; touch under the weather; dicky; sick; poorly hot baking; boiling; scorching; warm cold freezing; chilly; Baltic◊ annoyed nowty∆; frustrated; pissed off; miffed; peeved -

LANGUAGE VARIETY in ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England

LANGUAGE VARIETY IN ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England One thing that is important to very many English people is where they are from. For many of us, whatever happens to us in later life, and however much we move house or travel, the place where we grew up and spent our childhood and adolescence retains a special significance. Of course, this is not true of all of us. More often than in previous generations, families may move around the country, and there are increasing numbers of people who have had a nomadic childhood and are not really ‘from’ anywhere. But for a majority of English people, pride and interest in the area where they grew up is still a reality. The country is full of football supporters whose main concern is for the club of their childhood, even though they may now live hundreds of miles away. Local newspapers criss-cross the country in their thousands on their way to ‘exiles’ who have left their local areas. And at Christmas time the roads and railways are full of people returning to their native heath for the holiday period. Where we are from is thus an important part of our personal identity, and for many of us an important component of this local identity is the way we speak – our accent and dialect. Nearly all of us have regional features in the way we speak English, and are happy that this should be so, although of course there are upper-class people who have regionless accents, as well as people who for some reason wish to conceal their regional origins. -

Enregisterment in Historical Contexts

0 Enregisterment in Historical Contexts: A Framework Paul Stephen Cooper A thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics February 2013 1 ABSTRACT In this thesis I discuss how the phenomena of indexicality and enregisterment (Silverstein 2003; Agha 2003) can be observed and studied in historical contexts via the use of historical textual data. I present a framework for the study of historical enregisterment which compares data from corpora of both nineteenth-century and modern Yorkshire dialect material, and the results of an online survey of current speakers so as to ascertain the validity of the corpus data and to use ‘the present to explain the past’ (Labov 1977:226). This framework allows for the identification of enregistered repertoires of Yorkshire dialect in both the twenty-first and nineteenth centuries. This is achieved by combining elicited metapragmatic judgements and examples of dialect features from the online survey with quantitative frequency analysis of linguistic features from Yorkshire dialect literature and literary dialect (Shorrocks 1996) and qualitative metapragmatic discourse (Johnstone et al 2006) from sources such as dialect dictionaries, dialect grammars, travel writing, and glossaries. I suggest that processes of enregisterment may operate along a continuum and that linguistic features may become ‘deregistered’ as representative of a particular variety; I also suggest that features may become ‘deregistered’ to the point of becoming ‘fossil forms’, which is more closely related to Labov’s (1972) definition of the ultimate fate of a linguistic stereotype. I address the following research questions: 1. -

Chapter 1. Introduction

1 Chapter 1. Introduction Once an English-speaking population was established in South Africa in the 19 th century, new unique dialects of English began to emerge in the colony, particularly in the Eastern Cape, as a result of dialect levelling and contact with indigenous groups and the L1 Dutch speaking population already present in the country (Lanham 1996). Recognition of South African English as a variety in its own right came only later in the next century. South African English, however, is not a homogenous dialect; there are many different strata present under this designation, which have been recognised and identified in terms of geographic location and social factors such as first language, ethnicity, social class and gender (Hooper 1944a; Lanham 1964, 1966, 1967b, 1978b, 1982, 1990, 1996; Bughwan 1970; Lanham & MacDonald 1979; Barnes 1986; Lass 1987b, 1995; Wood 1987; McCormick 1989; Chick 1991; Mesthrie 1992, 1993a; Branford 1994; Douglas 1994; Buthelezi 1995; Dagut 1995; Van Rooy 1995; Wade 1995, 1997; Gough 1996; Malan 1996; Smit 1996a, 1996b; Görlach 1998c; Van der Walt 2000; Van Rooy & Van Huyssteen 2000; de Klerk & Gough 2002; Van der Walt & Van Rooy 2002; Wissing 2002). English has taken different social roles throughout South Africa’s turbulent history and has presented many faces – as a language of oppression, a language of opportunity, a language of separation or exclusivity, and also as a language of unification. From any chosen theoretical perspective, the presence of English has always been a point of contention in South Africa, a combination of both threat and promise (Mawasha 1984; Alexander 1990, 2000; de Kadt 1993, 1993b; de Klerk & Bosch 1993, 1994; Mesthrie & McCormick 1993; Schmied 1995; Wade 1995, 1997; de Klerk 1996b, 2000; Granville et al. -

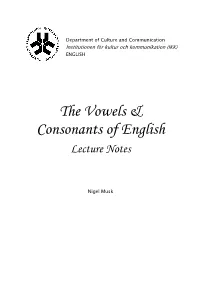

The Vowels & Consonants of English

Department of Culture and Communication Institutionen för kultur och kommunikation (IKK) ENGLISH The Vowels & Consonants of English Lecture Notes Nigel Musk The Consonants of English - - - Velar (Post Labio dental Palato Dental Palatal Glottal Bilabial alveolar alveolar) Alveolar Unvoiced (-V) -V +V -V +V -V +V -V +V -V +V -V +V -V +V -V +V Voiced (+V) Stops (Plosives) p b t d k g ʔ1 Fricatives f v θ ð s z ʃ ʒ h Affricates ʧ ʤ Nasals m n ŋ Lateral (approximants) l Approximants w2 r j w2 The consonants in the table above are the consonant phonemes of RP (Received Pronunciation) and GA (General American), that is, the meaning-distinguishing consonant sounds (c.f. pat – bat). Phonemes are written within slashes //, e.g. /t/. Significant variations are explained in the footnotes. /p/ put, supper, lip /ʃ/ show, washing, cash /b/ bit, ruby, pub /ʒ/ leisure, vision 3 /t/ two, letter , cat /h/ home, ahead 3 /d/ deep, ladder , read /ʧ/ chair, nature, watch /k/ can, lucky, sick /ʤ/ jump, pigeon, bridge /g/ gate, tiger, dog /m/ man, drummer, comb /f/ fine, coffee, leaf /n/ no, runner, pin /v/ van, over, move /ŋ/ young, singer 4 /θ/ think, both /l/ let , silly, fall /ð/ the, brother, smooth /r/ run, carry, (GA car) /s/ soup, fussy, less /j/ you, yes /z/ zoo, busy, use /w/ woman, way 1 [ʔ] is not regarded as a phoneme of standard English, but it is common in many varieties of British English (including contemporary RP), e.g. watch [wɒʔʧ], since [sɪnʔs], meet them [ˈmiːʔðəm]. -

From "RP" to "Estuary English"

From "RP" to "Estuary English": The concept 'received' and the debate about British pronunciation standards Hamburg 1998 Author: Gudrun Parsons Beckstrasse 8 D-20357 Hamburg e-mail: [email protected] Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................i List of Abbreviations............................................................................... ii 0. Introduction ....................................................................................1 1. Received Pronunciation .................................................................5 1.1. The History of 'RP' ..................................................................5 1.2. The History of RP....................................................................9 1.3. Descriptions of RP ...............................................................14 1.4. Summary...............................................................................17 2. Change and Variation in RP.............................................................18 2.1. The Vowel System ................................................................18 2.1.1. Diphthongisation of Long Vowels ..................................18 2.1.2. Fronting of /!/ and Lowering of /"/................................21 2.2. The Consonant System ........................................................23 2.2.1. The Glottal Stop.............................................................23 2.2.2. Vocalisation of [#]...........................................................26 -

Ba Chelor Thesis

English (61-90), 30 credits BACHELOR BACHELOR Received Pronunciation, Estuary English and Cockney English: A Phonologic and Sociolinguistic Comparison of Three British English Accents THESIS Caroline Johansson English linguistics, 15 credits Lewes, UK 2016-06-27 Abstract The aim of this study is to phonologically and sociolinguistically compare three British English accents: Cockney English (CE), Estuary English (EE) and Received Pronunciation (RP), including investigating the status these accents have in Britain today. Estuary English, which is spoken in London and the Home Counties, is said to be located on a continuum between Cockney English, which is a London working class accent, and Received Pronunciation, spoken by the higher classes in Britain. Four authentic Youtube lectures by an author who considers herself to be an EE speaker were compared with previous research in the area. The findings regarding phonetic differences between the accents displayed many opposing opinions between the Youtube material and the previous research. This is likely to be partly because of regional and social differences, and partly because of the fact that accents change and also depend on the formality of the situation in which they are spoken. Furthermore, accents are not clearly defined units and Estuary English has been shown to be many different accents that also figure on a broad spectrum between Received Pronunciation and Cockney English (and any other regional accents that are spoken in the area). When it comes to attitudes to the three different accents, the Youtube material and previous research seem to agree on most levels: RP can be perceived as cold and reserved and is not the only accepted accent today for people who wish to acquire a high status job, at the same time as it is still associated with the highest prestige.