Reviews Marvels & Tales Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Off the Pedestal, on the Stage: Animation and De-Animation in Art

Off the Pedestal; On the Stage Animation and De-animation in Art and Theatre Aura Satz Slade School of Fine Art, University College, London PhD in Fine Art 2002 Abstract Whereas most genealogies of the puppet invariably conclude with robots and androids, this dissertation explores an alternative narrative. Here the inanimate object, first perceived either miraculously or idolatrously to come to life, is then observed as something that the live actor can aspire to, not necessarily the end-result of an ever evolving technological accomplishment. This research project examines a fundamental oscillation between the perception of inanimate images as coming alive, and the converse experience of human actors becoming inanimate images, whilst interrogating how this might articulate, substantiate or defy belief. Chapters i and 2 consider the literary documentation of objects miraculously coming to life, informed by the theology of incarnation and resurrection in Early Christianity, Byzantium and the Middle Ages. This includes examinations of icons, relics, incorrupt cadavers, and articulated crucifixes. Their use in ritual gradually leads on to the birth of a Christian theatre, its use of inanimate figures intermingling with live actors, and the practice of tableaux vivants, live human figures emulating the stillness of a statue. The remaining chapters focus on cultural phenomena that internalise the inanimate object’s immobility or strange movement quality. Chapter 3 studies secular tableaux vivants from the late eighteenth century onwards. Chapter 4 explores puppets-automata, with particular emphasis on Kempelen's Chess-player and the physical relation between object-manipulator and manipulated-object. The main emphasis is a choreographic one, on the ways in which live movement can translate into inanimate hardness, and how this form of movement can then be appropriated. -

The Adventures of Pinocchio

Carlo Collodi The Adventures of Pinocchio Translated by P. M. D. Panton © Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi, Pescia, 2014, tutti i diritti riservati. La Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi mette questo testo a disposizione degli utenti del sito web www.pinocchio.it per uso esclusivamente personale e di studio. Ogni utilizzo commerciale e/o editoriale deve essere preventivamente autorizzato in forma scritta dalla Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi. In ogni caso, si prega di citare la fonte quando questo testo o sue parti vengono menzionate. © Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi, Pescia, 2014, all rights reserved. The Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi (National Carlo Collodi Foundation) makes this text available for its web site www.pinocchio.it users, for personal and research use and purposes only. Any commercial or publishing use of this text is to be previously authorized By the Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi in written form. In any case, the source is to be credited when this text or parts of it are quoted. THE ADVENTURES OF PINOCCHIO Traduzione integrale inglese di Le Avventure di Pinocchio. Storia di un burattino , di Carlo Collodi Tradotto da P. M. D.Panton – Copyright e proprietà letteraria riservata della Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi Chapter 1 How it happened that Master Cherry, the carpenter, found a piece of wood that wept and laughed like a child. There was once upon a time… "A king!" my little readers will say all at once. No, children, you are mistaken. Once upon a time there was a piece of wood. No, it was not an expensive piece of wood. Far from it. -

![[FREE] the Adventures of Zelda: a Pug Tale Cheats, Cheat Codes, Gamecheats, Game Index (T) - Cheatbook Games Index (T)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8559/free-the-adventures-of-zelda-a-pug-tale-cheats-cheat-codes-gamecheats-game-index-t-cheatbook-games-index-t-1318559.webp)

[FREE] the Adventures of Zelda: a Pug Tale Cheats, Cheat Codes, Gamecheats, Game Index (T) - Cheatbook Games Index (T)

[PDF-o3g]The Adventures of Zelda: A Pug Tale The Adventures of Zelda: A Pug Tale Cowboy Pug (The Adventures of Pug): Laura ... - amazon.com Two's A Crowd (Pug Pals #1): Flora Ahn: 9781338118452 ... Cheats, Cheat Codes, Gamecheats, Game index (T) - CheatBook Tue, 30 Oct 2018 11:16:00 GMT Cowboy Pug (The Adventures of Pug): Laura ... - amazon.com Cowboy Pug (The Adventures of Pug) [Laura James, Églantine Ceulemans] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Pug and his faithful companion, Lady Miranda, are going to be cowboys for the day--and first of all Two's A Crowd (Pug Pals #1): Flora Ahn: 9781338118452 ... This is THE perfect book for young readers that are too advanced for leveled books (Step 1, 2, 3 etc) but not quite ready for actual chapter books (think Ramona). [FREE] The Adventures of Zelda: A Pug Tale Cheats, Cheat Codes, Gamecheats, Game index (T) - CheatBook Games index (T). CheatBook is the resource for the latest Cheats, Hints, FAQ and Walkthroughs, Cheats, codes, hints, games. Download Vanellope von Schweetz | Disney Wiki | FANDOM powered by Wikia Vanellope von Schweetz is a featured article, which means it has been identified as one of the best articles produced by the Disney Wiki community. If you see a way this page can be updated or improved without compromising previous work, please feel free to contribute. Sat, 03 Nov 2018 09:45:00 GMT Cheatbook - Cheat Codes, Cheats, Trainer, Database, Hints Cheatbook your source for Cheats, Video game Cheat Codes and Game Hints, Walkthroughs, FAQ, Games Trainer, Games Guides, Secrets, cheatsbook Download Obstacle & Skill Games | 1000+ Free Flash Games | Andkon .. -

Revista Inclusiones Issn 0719-4706 Volumen 7 – Número Especial – Octubre/Diciembre 2020

CUERPO DIRECTIVO Mg. Amelia Herrera Lavanchy Universidad de La Serena, Chile Director Dr. Juan Guillermo Mansilla Sepúlveda Mg. Cecilia Jofré Muñoz Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile Universidad San Sebastián, Chile Editor Mg. Mario Lagomarsino Montoya OBU - CHILE Universidad Adventista de Chile, Chile Editor Científico Dr. Claudio Llanos Reyes Dr. Luiz Alberto David Araujo Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile Pontificia Universidade Católica de Sao Paulo, Brasil Dr. Werner Mackenbach Editor Europa del Este Universidad de Potsdam, Alemania Dr. Aleksandar Ivanov Katrandzhiev Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica Universidad Suroeste "Neofit Rilski", Bulgaria Mg. Rocío del Pilar Martínez Marín Cuerpo Asistente Universidad de Santander, Colombia Traductora: Inglés Ph. D. Natalia Milanesio Lic. Pauline Corthorn Escudero Universidad de Houston, Estados Unidos Editorial Cuadernos de Sofía, Chile Dra. Patricia Virginia Moggia Münchmeyer Portada Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile Lic. Graciela Pantigoso de Los Santos Editorial Cuadernos de Sofía, Chile Ph. D. Maritza Montero Universidad Central de Venezuela, Venezuela COMITÉ EDITORIAL Dra. Eleonora Pencheva Dra. Carolina Aroca Toloza Universidad Suroeste Neofit Rilski, Bulgaria Universidad de Chile, Chile Dra. Rosa María Regueiro Ferreira Dr. Jaime Bassa Mercado Universidad de La Coruña, España Universidad de Valparaíso, Chile Mg. David Ruete Zúñiga Dra. Heloísa Bellotto Universidad Nacional Andrés Bello, Chile Universidad de Sao Paulo, Brasil Dr. Andrés Saavedra Barahona Dra. Nidia Burgos Universidad San Clemente de Ojrid de Sofía, Bulgaria Universidad Nacional del Sur, Argentina Dr. Efraín Sánchez Cabra Mg. María Eugenia Campos Academia Colombiana de Historia, Colombia Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México Dra. Mirka Seitz Dr. Francisco José Francisco Carrera Universidad del Salvador, Argentina Universidad de Valladolid, España Ph. -

Pinocchio La Metafora Della Vita

Le avventure di Pinocchio Carlo Collodi The adventures of Pinocchio Carlo Collodi LA METAFORA DELLA VITA THE METAPHOR OF LIFE Rielaborazione Grafico pittorica riflessiva della fiaba di C.Collodi Classe IVC Castel San Giovanni Ins. Agnese Bollani A tale by C.Collodi revisited and illustrated by Classe/Class IVC Castel San Giovanni Ins. /TeacherAgnese Bollani GEPPETTO E' UN FALEGNAME POVERO E SENZA FIGLI. UN GIORNO PRENDE UNO STRANO PEZZO DI LEGNO E COSTRUISCE UN BURATTINO. GEPPETTO IS A POOR CARPENTER AND HE HAS NO CHILDREN. ONE DAY HE TAKES A STRANGE PIECE OF WOOD AND MAKES A PUPPET. NASCERE E' FACILE... COMING TO LIFE ISN'T DIFFICULT... GEPPETTO COSTRUISCE UNA TESTA E DUE OCCHI, UN NASO E UNA BOCCA, DUE BRACCIA, DUE MANI, DUE GAMBE E DUE PIEDI. PINOCCHIO E' BELLO E GEPPETTO E‘ FELICE ! HE MAKES A HEAD AND TWO EYES, A NOSE AND A MOUTH, TWO ARMS, TWO HANDS, TWO LEGS AND TWO FEET. PINOCCHIO IS BEAUTIFUL AND GEPPETTO IS VERY HAPPY ! OGNUNO DI NOI E' BELLO PERCHE' UNICO E ORIGINALE. THE NICEST THING OF BEING DIFFERENT IS THAT EVERYONE IS SPECIAL. IMMEDIATAMENTE IL BURATTINO COMINCIA A SALTARE TUTT'INTORNO. PINOCCHIO ESCE PER SCOPRIRE IL MONDO. IMMEDIATELY THE PUPPET STARTS JUMPING AROUND. PINOCCHIO GOES OUT AND WANTS TO DISCOVER THE WORLD. LA CURIOSITA' E' NATURALE. CI SONO PERICOLI, MA, SE LI CONOSCI, PUOI EVITARLI E VIVERE SICURO. BEING CURIOUS IS A NATURAL THING BUT DO NOT FORGET TO TAKE SAFETY INTO ACCOUNT. PINOCCHIO CAMMINA E CAMMINA... TORNA A CASA E HA FAME. TROVA UN UOVO, MA DAL GUSCIO ESCE UN PULCINO CHE VOLA VIA. -

The Goldfish and Little Red Riding Hood: Characters and Their Combinations in Fairy Tale Jokes and Parodies*

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 13 (1): 9–28 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2019-0002 THE GOLDFISH AND LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD: CHARACTERS AND THEIR COMBINATIONS IN FAIRY TALE JOKES AND PARODIES* RISTO JÄRV Head of the Archives, PhD Estonian Folklore Archives, Estonian Literary Museum Vanemuise 42, 51003 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT There are two types of joke that can be described as fairy tale jokes: those with punchlines that include fairy tale characters, and fairy tale parodies. The paper discusses fairy tale jokes that were sent to the jokes page of the major Estonian internet Web Portal Delfi by Internet users between 2000 and 2011, and jokes added by the editors of the portal between 2011 and 2018 (CFTJ). The joke corpus has had different addresses at different times, and was a live ‘folklore field’ for the first few years after creation. Of all the characters, the Goldfish appeared in the largest number of jokes (76 out of a total of 286 jokes), followed by Little Red Riding Hood (72). Other fairy tale characters feature in a 14 or fewer fairy tale jokes each. Several fairy tale jokes circulating on the Internet varied over the period observed. Fairy tale jokes generally get their impetus from the characters and from plots with unexpected outcomes. A seemingly innocent fairy tale character is often linked to a sexual theme: sexuality holds first place as the source of humour in fairy tale jokes, although this may be caused by the so-called genre code of jokes. KEYWORDS: fairy tale joke • fairy tale • joke • interpretation • parody Fairy tale characters are often iconic and need no explanation; they are likely to evoke associations with the full content of the tale and its web of relations in most people in the Western cultural sphere. -

Copertina Ferretti.Qxp Layout 1

2020 - N 16 ANNO VIII - N. 16 - APRILE 2020 - € 12,00 APRILE APRILE Production&Costume Design Magazine In questo numero: In this issue: Anfuso, Barthélémy, Burchiellaro, Buzzi, Capuano, Cecchi, Chiara, Di Monte, Ferretti, Fontaine, Foss, Fragola, Geleng, Lo Fazio, Mari, Medeiros, Meduri, Millenotti, E. Montaldo, G. Montaldo, Morong, Palli, Pascazi, Pescucci, Rabasse, Redini, Rubeo, Scola Di Mambro e un contributo di Italo Moscati COSTUME & ROMA LAZIO FILM PRONTI SCENOGRAFIA COMMISSIONA GIRARE Sognatori per Fellini Dreamers for Fellini Via Tuscolana 1055 - 00173 Roma Contatti +39 06 72286320/+390672286273 info@romalaziofilmcommission.it The Trial Version WWW.RO MALAZIOFILMCOMMISSIO N.IT A.S.C. The Trial Version A HISTORY OF ELEGANCE. Find out more about this story on MAGAZINE DI CINEMA, TEATRO E TELEVISIONE ANNO VIII - N. 16 SOMMARIO APRILE 2020 6 L’editoriale 32 luciano ricceri Quell’Oriente mitico costruito per Montaldo di Francesca Romana Buffetti 8 perspective That mythical East built for Montalto Da Hollywood, la rivista Al Teatro 5, il Seicento in pittura di Sara Montelupo degli scenografi di Francesca Romana Buffetti At the Teatro 5, the seventeenth century in painting From Hollywood, the art directors’ magazine Un ricordo di Elisabetta Montaldo A recollection 12 the costume designer guild All’Arena, tra nuvole e pagode di Nanà Cecchi Insieme per la categoria di Gary V. Foss At the Arena, among clouds and pagodas Together for the profession 16 il centenario Inventare: per Fellini significa costruire altri mondi di Italo Moscati Inventing: -

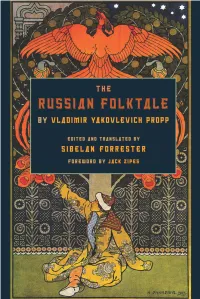

Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp

Series in Fairy-Tale Studies General Editor Donald Haase, Wayne State University Advisory Editors Cristina Bacchilega, University of Hawai`i, Mānoa Stephen Benson, University of East Anglia Nancy L. Canepa, Dartmouth College Isabel Cardigos, University of Algarve Anne E. Duggan, Wayne State University Janet Langlois, Wayne State University Ulrich Marzolph, University of Gött ingen Carolina Fernández Rodríguez, University of Oviedo John Stephens, Macquarie University Maria Tatar, Harvard University Holly Tucker, Vanderbilt University Jack Zipes, University of Minnesota A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu W5884.indb ii 8/7/12 10:18 AM THE RUSSIAN FOLKTALE BY VLADIMIR YAKOVLEVICH PROPP EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY SIBELAN FORRESTER FOREWORD BY JACK ZIPES Wayne State University Press Detroit W5884.indb iii 8/7/12 10:18 AM © 2012 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. English translation published by arrangement with the publishing house Labyrinth-MP. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data 880-01 Propp, V. IA. (Vladimir IAkovlevich), 1895–1970, author. [880-02 Russkaia skazka. English. 2012] Th e Russian folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp / edited and translated by Sibelan Forrester ; foreword by Jack Zipes. pages ; cm. — (Series in fairy-tale studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8143-3466-9 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 978-0-8143-3721-9 (ebook) 1. Tales—Russia (Federation)—History and criticism. 2. Fairy tales—Classifi cation. 3. Folklore—Russia (Federation) I. -

Role of the Folk Songs in the Russian Opera of the 18Th Century Adriana Pilip-Siroki

Role of the Folk Songs in the Russian Opera of the 18th Century Adriana Pilip-Siroki Listaháskóli Íslands Tónlistardeild Söngur Role of the Folk Songs in the Russian Opera of the 18th Century Adriana Pilip-Siroki Supervisor: Gunnsteinn Ólafsson Spring 2011 Abstract of the work The last decades of the 18th century were a momentous period in Russian history; they marked an ever-increasing awareness of the horrors of serfdom and the fate of peasantry. Because of the exposure of brutal treatment of the serfs, the public was agitating for big reforms. In the 18th century these historical circumstances and the political environment affected the artists. The folk song became widely reflected in Russian professional music of the century, especially in its most important genre, the opera. The Russian opera showed strong links with Russian folklore from its very first appearance. This factor differentiates it from all other genres of the 18th century, which were very much under the influence of classicism (painting, literature, architecture). About one hundred operas were created in the last decades of the 18th century, but only thirty remained; of which fifteen make use of Russian and Ukrainian folk music. Gathering of folk songs and the first attempts to affix them to paper were made in this period. In course of only twenty years, from its beginning until the turn of the century, Russian opera underwent a great change: it became into a fully-fledged genre. Russian opera is an important part of the world’s theatre music treasures, and the music of the 18th century was the foundation of the mighty achievements of the second half of the 19th century, embodied in the works of Mussorgsky, Tchaikovsky, Borodin, and Rimsky-Korsakov. -

LUX Radio Theater “Pinocchio” Originally Aired December 25, 1939

Lux Radio Theater- Pinocchio Page 1 of 40 LUX Radio Theater “Pinocchio” Originally aired December 25, 1939 Transcribed by Ben Dooley for “Those Thrilling Days of Yesteryear” old time radio recreations. www.ttdyradio.comH CAST: SFX: Announcer (Melville Ruick) - Evan Footsteps Cecil B. deMille - Don Picking up wooden puppet Jiminy Cricket- Ben Wood Crash Geppetto- Lars Door open/close/ knock Window Open Figaro- Aimee Splash water on face Cuckoo Clock Pinocchio walking/ running/ dancing/ falling Blue Fairy-Julie (wood) Pinocchio- Pam Unwrapping presents “Honest” John- John Corona Train sounds Gideon- Aaron Doll Saying “Ma-ma” Coins dropping Girl- Aimee Pinocchio thrown into wooden cage. Door shut. Boy- John Rattling cage and lock Peg- Julie Whip John (Husband)- Aaron Horse & cart move Sally- Joy Raining Stromboli- John Gould Wagon stops *BOING* (nose growing) Coachman-Don Lock opens & door swings open Lampwick- Evan Shooting pool Alexander- Joy Opening letter Donkey - Ocean waves Barker #1- Aaron Water pouring in. Waves. Barker #2- John Gould Water splashing around. Fire crackling Libby Collins- Joy Wind blowing Monstro- Raft crashing against the rocks ************************************ ANNOUNCER: Lux… presents, Hollywood. MUSIC: “Lux Theme” ANNOUNCER: (OVER MUSIC) The Lux Radio Theater brings you the new Walt Disney feature, “Pinocchio”. Ladies and gentlemen, your producer, Mr. Cecil B. deMille MUSIC: Ends Lux Radio Theater- Pinocchio Page 2 of 40 APPLAUSE DEMILLE: Greetings, from Hollywood, ladies and gentlemen. This is a night that weaves a spell over the world—a time of reverence and rejoicing. Of family reunions and storytelling by the fire. On this enchanted night, we can all believe implicitly in stories like Pinocchio. -

© 2014 Daniele De Feo ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2014 Daniele De Feo ALL RIGHTS RESERVED IL GUSTO DELLA MODERNITÀ: AESTHETICS, NATION, AND THE LANGUAGE OF FOOD IN 19TH CENTURY ITALY By DANIELE DE FEO A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Italian Written under the direction of Professor Paola Gambarota And approved by _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January, 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION IL GUSTO DELLA MODERNITÀ: AESTHETICS, NATION, AND THE LANGUAGE OF FOOD IN 19TH CENTURY ITALY By DANIELE DE FEO Dissertation Director Professor Paola Gambarota My dissertation “Il Gusto della Modernità: Aesthetics, Nation and the Language of Food in 19th century Italy,” explores the cohesive pedagogic and nationalistic attempt to define Italian taste during the instability of an unificatory Italy. Initiating with an establishing European taste paradigm (e.g. Feuerbach, Fourier, Brillat-Savarin), my research demonstrates that there is an increasing number of works composed within the developing “Italian” context, which reflects and participates in the construction and the consumption of a national identity (e.g., Rajberti, Mantegazza, Guerrini, Artusi). Conversely, this budding taste genre finds itself in sharp contrast to the economic paucity and social divisiveness endured by a large sector of the populace and depicted by the literature of the day (e.g., Collodi, Verga, Serao). It is precisely this lack of confluence between that which is scientific and literary that marks this process of taste ennoblement and indoctrination, defining more than ever the nuances that encompass il gusto italiano. -

Script Images & Sound Reference

THE GAME IS ON!: THE ADVENTURE OF THE GIRL WITH THE LIGHT BLUE HAIR – ANNOTATED SCRIPT IMAGES & SOUND REFERENCE 1.1 Exterior: Red Bus crossing From: Temple Island Collections Ltd v. New English Teas Ltd & another [2012] Westminster Bridge EWPCC 1 The opening sequence references the images at the heart of the litigation in Temple Island Collections reproduced below. The image on the left is the claimant’s work; the image on the right is the infringing copy. For further discussion see Case File #1: The Red Bus. 1.2 Once upon a time, in a fictional land From: Fables (comic), Issue 1 (2002), by Bill Willingham called London … This long-running and extraordinarily successful comic begins: ‘Once upon a time, in a fictional land called New York City …’ 1.3 Once upon a time, in a fictional land On-screen Text (design) From: The X-Files (1993-) called London … 221B Baker Street, The way in which the text appears on screen, accompanied by the sound of a NW1 6XE typewriter, mimics The X-Files, the long-running science fiction TV series. 1.4 Exterior: 221B Baker Street, NW1 6XE The external street scene is based on 221B Baker Street from the BBC Sherlock series; the actual location is North Gower Street, London. 1 THE GAME IS ON!: THE ADVENTURE OF THE GIRL WITH THE LIGHT BLUE HAIR – ANNOTATED 1.5 Gower’s (name) We changed the name of Speedy’s (from the BBC’s Sherlock) to Gower’s, referring to both the actual location of the street (North Gower Street) and the 2006 Gowers Review of Intellectual Property.