6 X 10 Long.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revista Inclusiones Issn 0719-4706 Volumen 7 – Número Especial – Octubre/Diciembre 2020

CUERPO DIRECTIVO Mg. Amelia Herrera Lavanchy Universidad de La Serena, Chile Director Dr. Juan Guillermo Mansilla Sepúlveda Mg. Cecilia Jofré Muñoz Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile Universidad San Sebastián, Chile Editor Mg. Mario Lagomarsino Montoya OBU - CHILE Universidad Adventista de Chile, Chile Editor Científico Dr. Claudio Llanos Reyes Dr. Luiz Alberto David Araujo Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile Pontificia Universidade Católica de Sao Paulo, Brasil Dr. Werner Mackenbach Editor Europa del Este Universidad de Potsdam, Alemania Dr. Aleksandar Ivanov Katrandzhiev Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica Universidad Suroeste "Neofit Rilski", Bulgaria Mg. Rocío del Pilar Martínez Marín Cuerpo Asistente Universidad de Santander, Colombia Traductora: Inglés Ph. D. Natalia Milanesio Lic. Pauline Corthorn Escudero Universidad de Houston, Estados Unidos Editorial Cuadernos de Sofía, Chile Dra. Patricia Virginia Moggia Münchmeyer Portada Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile Lic. Graciela Pantigoso de Los Santos Editorial Cuadernos de Sofía, Chile Ph. D. Maritza Montero Universidad Central de Venezuela, Venezuela COMITÉ EDITORIAL Dra. Eleonora Pencheva Dra. Carolina Aroca Toloza Universidad Suroeste Neofit Rilski, Bulgaria Universidad de Chile, Chile Dra. Rosa María Regueiro Ferreira Dr. Jaime Bassa Mercado Universidad de La Coruña, España Universidad de Valparaíso, Chile Mg. David Ruete Zúñiga Dra. Heloísa Bellotto Universidad Nacional Andrés Bello, Chile Universidad de Sao Paulo, Brasil Dr. Andrés Saavedra Barahona Dra. Nidia Burgos Universidad San Clemente de Ojrid de Sofía, Bulgaria Universidad Nacional del Sur, Argentina Dr. Efraín Sánchez Cabra Mg. María Eugenia Campos Academia Colombiana de Historia, Colombia Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México Dra. Mirka Seitz Dr. Francisco José Francisco Carrera Universidad del Salvador, Argentina Universidad de Valladolid, España Ph. -

The Goldfish and Little Red Riding Hood: Characters and Their Combinations in Fairy Tale Jokes and Parodies*

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 13 (1): 9–28 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2019-0002 THE GOLDFISH AND LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD: CHARACTERS AND THEIR COMBINATIONS IN FAIRY TALE JOKES AND PARODIES* RISTO JÄRV Head of the Archives, PhD Estonian Folklore Archives, Estonian Literary Museum Vanemuise 42, 51003 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT There are two types of joke that can be described as fairy tale jokes: those with punchlines that include fairy tale characters, and fairy tale parodies. The paper discusses fairy tale jokes that were sent to the jokes page of the major Estonian internet Web Portal Delfi by Internet users between 2000 and 2011, and jokes added by the editors of the portal between 2011 and 2018 (CFTJ). The joke corpus has had different addresses at different times, and was a live ‘folklore field’ for the first few years after creation. Of all the characters, the Goldfish appeared in the largest number of jokes (76 out of a total of 286 jokes), followed by Little Red Riding Hood (72). Other fairy tale characters feature in a 14 or fewer fairy tale jokes each. Several fairy tale jokes circulating on the Internet varied over the period observed. Fairy tale jokes generally get their impetus from the characters and from plots with unexpected outcomes. A seemingly innocent fairy tale character is often linked to a sexual theme: sexuality holds first place as the source of humour in fairy tale jokes, although this may be caused by the so-called genre code of jokes. KEYWORDS: fairy tale joke • fairy tale • joke • interpretation • parody Fairy tale characters are often iconic and need no explanation; they are likely to evoke associations with the full content of the tale and its web of relations in most people in the Western cultural sphere. -

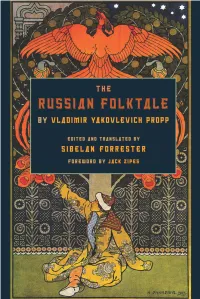

Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp

Series in Fairy-Tale Studies General Editor Donald Haase, Wayne State University Advisory Editors Cristina Bacchilega, University of Hawai`i, Mānoa Stephen Benson, University of East Anglia Nancy L. Canepa, Dartmouth College Isabel Cardigos, University of Algarve Anne E. Duggan, Wayne State University Janet Langlois, Wayne State University Ulrich Marzolph, University of Gött ingen Carolina Fernández Rodríguez, University of Oviedo John Stephens, Macquarie University Maria Tatar, Harvard University Holly Tucker, Vanderbilt University Jack Zipes, University of Minnesota A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu W5884.indb ii 8/7/12 10:18 AM THE RUSSIAN FOLKTALE BY VLADIMIR YAKOVLEVICH PROPP EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY SIBELAN FORRESTER FOREWORD BY JACK ZIPES Wayne State University Press Detroit W5884.indb iii 8/7/12 10:18 AM © 2012 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. English translation published by arrangement with the publishing house Labyrinth-MP. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data 880-01 Propp, V. IA. (Vladimir IAkovlevich), 1895–1970, author. [880-02 Russkaia skazka. English. 2012] Th e Russian folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp / edited and translated by Sibelan Forrester ; foreword by Jack Zipes. pages ; cm. — (Series in fairy-tale studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8143-3466-9 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 978-0-8143-3721-9 (ebook) 1. Tales—Russia (Federation)—History and criticism. 2. Fairy tales—Classifi cation. 3. Folklore—Russia (Federation) I. -

Role of the Folk Songs in the Russian Opera of the 18Th Century Adriana Pilip-Siroki

Role of the Folk Songs in the Russian Opera of the 18th Century Adriana Pilip-Siroki Listaháskóli Íslands Tónlistardeild Söngur Role of the Folk Songs in the Russian Opera of the 18th Century Adriana Pilip-Siroki Supervisor: Gunnsteinn Ólafsson Spring 2011 Abstract of the work The last decades of the 18th century were a momentous period in Russian history; they marked an ever-increasing awareness of the horrors of serfdom and the fate of peasantry. Because of the exposure of brutal treatment of the serfs, the public was agitating for big reforms. In the 18th century these historical circumstances and the political environment affected the artists. The folk song became widely reflected in Russian professional music of the century, especially in its most important genre, the opera. The Russian opera showed strong links with Russian folklore from its very first appearance. This factor differentiates it from all other genres of the 18th century, which were very much under the influence of classicism (painting, literature, architecture). About one hundred operas were created in the last decades of the 18th century, but only thirty remained; of which fifteen make use of Russian and Ukrainian folk music. Gathering of folk songs and the first attempts to affix them to paper were made in this period. In course of only twenty years, from its beginning until the turn of the century, Russian opera underwent a great change: it became into a fully-fledged genre. Russian opera is an important part of the world’s theatre music treasures, and the music of the 18th century was the foundation of the mighty achievements of the second half of the 19th century, embodied in the works of Mussorgsky, Tchaikovsky, Borodin, and Rimsky-Korsakov. -

Reviews Marvels & Tales Editors

Marvels & Tales Volume 30 Article 8 Issue 1 Rooted in Wonder 8-1-2016 Reviews Marvels & Tales Editors Recommended Citation Editors, Marvels & Tales. "Reviews." Marvels & Tales 30.1 (2016). Web. <http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/marvels/vol30/iss1/8>. REVIEWS Contes: Charles Perrault. Edited by Tony Gheeraert. Paris: Honoré Champion, 2012. 466 pp. This new French edition of Perrault’s fairy tales has the immense merit of being a comprehensive collection of Perrault’s writings in the genre, including his versified tales, prose tales (found in the 1695 manuscript, theMercure galant, and the 1697 edition), and prefaces, dedications, contemporary letters, and contemporary articles on the subject. The book is divided into four main parts, followed by outlines and notices of each tale, a bibliography, an index of the main mentioned names, and a table of illustrations. The first section is a long introduction. Next is Perrault’s versified tales and their prefaces. They are followed by the published tales of the 1697 Histoires ou contes du temps passé, including the dedication, illustrations, and an extract of the king’s privilege. The appendix constitutes the longest part of the book, in which the editor reproduces letters, the integral text of Perrault’s 1695 manuscript, the Mercure galant’s version of “La Belle au bois dormant,” some excerpts of Mercure galant’s articles on Perrault’s fairy tales, a prose version of “Peau d’Ane,” and a chap- book version of “Grisélidis.” The editor has chosen to reproduce the tales with modernized spelling and to signal the numerous typographic and orthographic mistakes and negligence of contemporary editions in the footnotes. -

Russian & Slavic

Encyclopedia of Russian & Slavic Myth and Legend Encyclopedia of Russian & Slavic Myth and Legend Mike Dixon-Kennedy Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 1998 by Mike Dixon-Kennedy All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dixon-Kennedy, Mike, 1959– Encyclopedia of Russian and Slavic myth and legend. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: Covers the myths and legends of the Russian Empire at its greatest extent as well as other Slavic people and countries. Includes historical, geographical, and biographical background information. 1. Mythology, Slavic—Juvenile literature. [1. Mythology, Slavic. 2. Mythology—Encyclopedias.] I. Title. BL930.D58 1998 398.2'0947—dc21 98-20330 CIP AC ISBN 1-57607-063-8 (hc) ISBN 1-57607-130-8 (pbk) 0403020100999810987654321 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 Typesetting by Letra Libre This book is printed on acid-free paper I. Manufactured in the United States of America. For Gill CONTENTS Preface, ix How to Use This Book, xi Brief Historical and Anthropological Details, xiii Encyclopedia of Russian and Slavic Myth and Legend, 1 References and Further Reading, 327 Appendix 1, 331 Glossary of Terms Appendix 2, 333 Transliteration from Cyrillic to Latin Letters Appendix 3, 335 The Rulers of Russia Appendix 4, 337 Topic Finder Index, 353 vii PREFACE Having studied the amazingly complex sub- This volume is not unique. -

Download Syllabus

RUSS 3301 /ENGL 3301: Russian Literature in Translation: Children’s Literature Spring 2019 Instructor: Iya Khelm Price Office Hours: MW 12:00-1:00PM or by Office number: HH 221E appointment Office Telephone Number: 817-272- Section Information: RUSS 3301-001 & 3161 (main office) ENGL 3301-001 Email Address: [email protected] Time and Place of Class Meetings: Faculty Profile: 01/14/2019 - 05/03/2019 https://www.uta.edu/profiles/iya-khelm F 1:00-3:50PM; TH119 Description of Course Content: Covers the works of major Russian authors during the period from the beginning of Russian literature until and after the 1917 Revolution, focusing on the interrelationship of various literary movements and philosophies. Students receiving credit in Russian will complete a research project using the Russian language. May be repeated for credit as topics and periods vary. Offered as ENGL 3301 and RUSS 3301; credit will be granted in only one department. Prerequisites: ENGL 3301-English majors must have earned a C or better in ENGL 2350 or must be concurrently enrolled in ENGL 2350. Non-majors must have earned a C or better in 6 hours of sophomore literature (ENGL 2303, ENGL 2309, ENGL 2319, ENGL 2329) or an A in 3 hours of sophomore literature (ENGL 2303, ENGL 2309, ENGL 2319, ENGL 2329). RUSS 3301-RUSS 2314 or equivalent with a grade of C or better, or knowledge of the language and permission of the instructor. Student Learning Outcomes: Upon successfully completing this course, students should be able to: • Recognize specifics of Russian children’s literature; • Use methods of children’s literature analysis; • Know most common genres and components of Russian children’s literature; • Plan creative projects related to study of children’s literature and working with children; • Compare works of Russian children’s literature with works of children’s literature of other nations. -

A Russian Fairy Tale in Tlingit Oral Tradition

Oral Tradition, 13/1 (1998): 58-91 Tracking “Yuwaan Gagéets”: A Russian Fairy Tale in Tlingit Oral Tradition Nora Marks Dauenhauer and Richard L. Dauenhauer Dedicated to the Memory of Anny Marks / Shkaxwul.aat (1898-1963) Willie Marks / Keet Yaanaayí (1902-1981) Susie James / Kaasgéiy (1890-1980) Robert Zuboff / Shaadaax' (1893-1974) Tracking “Yuwaan Gagéets” has involved many levels of the collaborative process in folklore transmission and research. The borrowing and development of “Gagéets” as a story in Tlingit oral tradition, as well as its discovery and documentation by folklorists, offer complex examples of collaboration. Neither the process of borrowing nor of documentation would have been possible without the dynamics of collaboration. In general, comparatists and folklorists today seem less concerned with problems of direct influence, borrowing, and migration than they were in earlier periods of scholarship. But now and then a classic migratory situation affords itself, and a story comes to light, the uniqueness of which is best illuminated by a traditional historical-geographical approach. Such a story is the tale of “Yuwaan Gagéets,” which we analyze here to study the process of borrowing in Tlingit oral tradition and to contrast the minimal European influence in the repertoire of Tlingit oral literature with the widespread exchange of songs, stories, and motifs among the Indians of the Northwest Coast. Our study also presents an example of collaborative research. This paper, revised in 1994-95, subsumes research activities that go back as far as sixty years. Although the story of “Gagéets” is older, our story here begins with the childhood of Nora Marks Dauenhauer, who grew up hearing oral versions in Tlingit, and with the academic training of Richard Dauenhauer, who read the Russian version as a student of that language. -

SFU Thesis Template Files

Slackers, Fools, Robbers and Thieves: Fairy Tales and the Folk Imagination by Dariya Prykhodko M.A.(Russian Language and Literature), University of Franko, Ukraine, 1998 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Liberal Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Dariya Prykhodko 2014 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2014 Approval Name: Dariya Prykhodko Degree: Master of Arts Title: Slackers, Fools, Robbers and Thieves: Fairy Tales and the Folk Imagination Supervisory Committee: Chair: Eleanor Stebner Associate Professor J.S. Woodsworth Chair, Humanities June Sturrock Senior Supervisor Professor Emerita, English Jerry Zaslove Supervisor Professor Emeritus, English Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor Emeritus, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: March 19, 2014 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract As has been noted by many linguists and folklorists, folklore - like language - has a naturally collective ownership,f and thus, it is subject to strict uniform laws: only those features that do not fail to hold attraction to their audience survive throughout time and changing life circumstances. I look at several conventionally negative types of the folktale hero, such as the Fool, the Slacker, the Trickster, the Robber and the Thief, which – nevertheless – hold a steady popularity in folklore, as can be seen in the two best-known Russian and German folktale collections. I attempt to investigate various psychological, cultural and historical causes that may have produced these types and contributed to their seemingly irrational appeal to the audience. Another cultural question that interests students of the folktale is whether there is a national mentality that can be traced via folklore. -

Fairytale Women: Gender Politics in Soviet and Post-Soviet Animated Adaptations of Russian National Fairytales

FAIRYTALE WOMEN: GENDER POLITICS IN SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET ANIMATED ADAPTATIONS OF RUSSIAN NATIONAL FAIRYTALES NADEZDA FADINA This is a digitised version of a dissertation submitted to the University of Bedfordshire. It is available to view only. This item is subject to copyright. FAIRYTALE WOMEN: GENDER POLITICS IN SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET ANIMATED ADAPTATIONS OF RUSSIAN NATIONAL FAIRYTALES by NADEZDA FADINA MA in International Cinema (Commendation) A thesis submitted to the University of Bedfordshire in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bedfordshire Research School for Media, Arts and Performance January, 2016 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own unaided work. It is being submitted for the degree of Ph.D at the University of Bedfordshire. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination in any other University. Name of candidate: Nadezda Fadina Signature: Date: FAIRYTALE WOMEN: GENDER POLITICS IN SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET ANIMATED ADAPTATIONS OF RUSSIAN NATIONAL FAIRYTALES. NADEZDA FADINA Abstract Despite the volume of research into fairytales, gender and ideology in media studies, the specific subject of animated adaptations of national fairytales and their role in constructing gender identities remains a blind spot at least in relation to non-Western and non-Hollywood animation. This study addresses the gap by analysing animated adaptations of Russian national fairytales in Soviet and post-Soviet cinema and television. It does so as a tool through which to approach the gender politics of the dominant ideologies in national cinema and also, though to a lesser extent, in television. One of the key perspectives this research adopts concerns the reorganization of the myths of femininity, as stored in ‘national memory’ and transferred through the material of national fairytales produced during a century-long period. -

Folktales.Pdf

Eglė, Queen of the Sea Serpents (Lithuania) Once upon a time, long, long ago, there lived an old man and his wife. They had twelve sons and three daughters. The youngest was named Eglė. One summer evening all three sisters went bathing. After splashing around and washing, they returned to shore to dress. Suddenly the youngest sees a sea serpent coiled in the sleeve of her blouse. What to do? The oldest sister grabbed a stick and was ready to drive the serpent away, but he turned to the youngest and began speaking in a human voice: “Dear Egle,” he says, - give me your word that you will marry me and I will leave peaceably!” Eglė began crying. After all, how can she marry a serpent! Then she spoke up angrily: „Give me back my blouse and go back unhurt where you came from!" But the sea serpent didn’t budge: “Give me your word,” says he, “that you will marry me and I will leave peaceably.” “Go ahead and promise, little Egle. You don’t really believe you’ll have to marry him?!” said the oldest sister scornfully. So Eglė promised to marry the sea serpent. After returning home they forgot about the serpent. Three days went by. They hear a commotion in the yard. They look - a throng of sea serpents are slithering into their yard. Frightened, they watch the serpents swarm toward their house, climb and wriggle up its sides, coil around the porch posts. The matchmakers simply barged into the house to negotiate with the oldsters and the young bride.