School of Arts and Social Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Union Addressed • S/2002/979 (29 August 2002) Was Peace and Security in Africa

SECURITY COUNCIL REPORT 2011 No. 2 10 May 2011 SPECIAL RESEARCH REPORT This report and links to all of the relevant documents are available on our website at www.securitycouncilreport.org Working TogeTher for Peace and SecuriTy in africa: The Security council and the AU Peace and Security council TABLE OF CONTENTS 9. The AU PSC-UN Security This Special Research Report 1. Introduction .................................1 Council Relationship ................23 responds to a growing interest in 2. Historical Context .......................3 10. Trying to Put Things in how to improve the joint efforts of 2.1 UN Chapter VIII Relationships ......3 Perspective .................................26 both the UN Security Council and the AU Peace and Security Council 2.2 The AU Comes into Being ............4 11. Council and Wider Dynamics ...28 to prevent and end violent conflicts 3. The AU Structural Design ..........5 11.1 Political Perspectives from in Africa. For almost six years SCR 4. The AU’s Peace and Security the Past ........................................28 has been analysing these efforts in System ..........................................6 11.2 Current Political Dynamics .........30 country-specific situations and at 4.1 The PSC’s Structure and 12. The Way Ahead ......................... 32 the thematic level. But with the tenth Working Methods..........................6 13. UN Documents ......................... 33 anniversary of the AU inauguration 4.2 The Continental Early 14. AU Documents.......................... 37 just over a year away it seemed Warning System ............................7 Appendix ................................... 38 clear that the relationship still had 4.3 The Panel of the Wise ...................7 many problems and was very far 4.4 The African Standby Force away from realising its potential for being an effective partnership. -

United Nations Private Sector Forum on the Millennium Development Goals

MEETING REPORT UNITED NATIONS PRIVATE SECTOR FORum on the Millennium Development Goals 22 SEPTEMBER 2010, NEW YORK 2 UN Private Sector Forum Organizing Committee Members: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), International Finance Corporation (IFC), International Fund for Agricultural Develop- ment (IFAD), International Labour Organization (ILO), Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM, part of UN Women), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), United Nations Foundation (UNF), United Nations Global Compact Office, United Nations Office for Partnerships (UNOP), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), World Bank, World Food Programme (WFP). Photos: © UN Global Compact/Michael Dames 3 Table of Contents Executive Summary 6 Commitments to Development 8 2010 Commitments 8 Tracking 2008 Commitments 9 Welcome and Opening Addresses 12 Luncheon Keynote Remarks 15 Thematic Discussions – Advancing Solutions through Business Innovation 16 Poverty and Hunger 18 Maternal and Child Health and HIV/AIDS 20 Access to Education through Innovative Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) 22 Innovations for Financial Inclusion 24 Empowering Women and Achieving Equality 26 Green Economy 28 Closing Addresses 30 Appendices 31 Accelerating Private Sector Action to Help Close MDG Gaps – Key Messages 31 Bilateral Donors’ Statement in Support of Private Sector Partnerships for Development 33 Agenda 35 Participant List 39 4 “ An investment in the MDGs is an investment in growth, prosperity and the markets of the future — a win-win proposition.” – H.E. -

Permanent Missions to the United Nations

Permanent Missions to the United Nations ST/SG/SER.A/300 Executive Office of the Secretary-General Protocol and Liaison Service Permanent Missions to the United Nations Nº 300 March 2010 United Nations, New York Note: This publication is prepared by the Protocol and Liaison Service for information purposes only. The listings relating to the permanent missions are based on information communicated to the Protocol and Liaison Service by the permanent missions, and their publication is intended for the use of delegations and the Secretariat. They do not include all diplomatic and administrative staff exercising official functions in connection with the United Nations. Further information concerning names of members of permanent missions entitled to diplomatic privileges and immunities and other mission members registered with the United Nations can be obtained from: Protocol and Liaison Service Room NL-2058 United Nations New York, N.Y., 10017 Telephone: (212) 963-7174 Telefax: (212) 963-1921 website: http://www.un.int/protocol All changes and additions to this publication should be communicated to the above Service. Contents I. Member States maintaining permanent missions at Headquarters Afghanistan.......... 2 Czech Republic..... 71 Kenya ............. 144 Albania .............. 3 Democratic People’s Kuwait ............ 146 Algeria .............. 4 Republic Kyrgyzstan ........ 148 Andorra ............. 6 of Korea ......... 73 Lao People’s Angola .............. 7 Democratic Republic Democratic Antigua of the Congo ..... 74 Republic ........ 149 and Barbuda ...... 9 Denmark ........... 75 Latvia ............. 150 Argentina ........... 10 Djibouti ............ 77 Lebanon........... 151 Armenia ............ 12 Dominica ........... 78 Lesotho ........... 152 Australia............ 13 Dominican Liberia ............ 153 Austria ............. 15 Republic ......... 79 Libyan Arab Azerbaijan.......... 18 Ecuador ............ 81 Jamahiriya ...... 154 Bahamas............ 19 Egypt.............. -

Gustavocarbonarorodri

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÕES E ARTES GUSTAVO CARBONARO RODRIGUES Narrativas brasileiras: identidade e discurso diplomático no governo Lula São Paulo 2015 GUSTAVO CARBONARO RODRIGUES Narrativas brasileiras: identidade e discurso diplomático no governo Lula Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências da Comunicação. Área de Concentração: Interfaces Sociais da Comunicação Linha de Pesquisa: Políticas e Estratégias de Comunicação Orientador: Prof. Dr. Paulo Roberto Nassar de Oliveira São Paulo 2015 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Catalogação na publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo Dados fornecidos pelo autor Rodrigues, Gustavo Carbonaro. Narrativas brasileiras: Identidade e discurso diplomático no governo Lula / Gustavo Carbonaro Rodrigues. -- São Paulo: G. C. Rodrigues, 2015. 283p. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Comunicação - Escola de Comunicações e Artes / Universidade de São Paulo. Orientador: Paulo Roberto Nassar de Oliveira Bibliografia 1. Discurso diplomático. 2. Identidade nacional. 3. Mito Nacional. 4. Narrativa de país. 5. Novas narrativas. 6. Política Externa. I. Nassar, Paulo II. Título III. Título. Nome: RODRIGUES, Gustavo Carbonaro Título: Narrativas brasileiras: identidade e discurso diplomático no governo Lula Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências da Comunicação. Aprovado em: _____/_____/ 2015 Banca Examinadora Prof. Dr.: __________________________________________________________________ Instituição: __________________________________________________________________ Julgamento: _________________________ Assinatura: _____________________________ Prof. -

General Assembly Official Records Sixty-Fourth Session

United Nations A/64/PV.93 General Assembly Official Records Sixty-fourth session 93rd plenary meeting Friday, 11 June 2010, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Ali Abdussalam Treki........................... (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya) The meeting was called to order at 10.15 a.m. I would like to congratulate His Excellency Joseph Deiss, former President of the Swiss Agenda item 4 Confederation, on his election as the President of the sixty-fifth session of the General Assembly. Election of the President of the General Assembly I would also like to take this opportunity to Election of the President of the General acknowledge and welcome the presence of the Minister Assembly for the sixty-fifth session for Foreign Affairs of the Swiss Confederation, Her The President (spoke in Arabic): In accordance Excellency Ms. Micheline Calmy-Rey. with rule 30 of the rules of procedure of the General I am sure that Member States appreciate the Assembly, I now invite members of the General wealth of knowledge and experience that Mr. Deiss Assembly to proceed to the election of the President of brings to this high office, which will enable him to the General Assembly for the sixty-fifth session. carry forward our collective endeavour and further May I recall that, in accordance with paragraph 1 advance the important work of the General Assembly. of the annex to General Assembly resolution 33/138, of His perspective as a result of having served as Minister 19 December 1978, the President of the General of Foreign Affairs and Minister of Economy of Assembly for the sixty-fifth session should be elected Switzerland will certainly guide and benefit the from among the Group of Western European and other discussions related to the whole host of issues and States. -

A Different World Cannot Be Built by Indifferent People

Permanent Mission of Italy to the United Nations DIPLOMACY AND ARTS: ITALY AT THE UNITED NATIONS Italian Army - United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) AN OVERVIEW OF THE ITALIAN ACTIVITIES AT THE 64th GENERAL ASSEMBLY (2009 – 2010) DIPLOMACY AND ARTS: ITALY AT THE UNITED NATIONS AN OVERVIEW OF THE ITALIAN ACTIVITIES AT THE 64th GENERAL ASSEMBLY (2009 – 2010) Editorial staff : Silvia Cioce Michael Moore Angela Carabelli Riccardo Chioni Francesca Lorusso Caputi Printed by Hermitage Press, Inc., Trenton NJ A publication of the Italian Permanent Mission to the United Nations – www.italyun.esteri.it Edition December 2010. 2 3 “Il linguaggio e’ stato lavorato dagli uomini per intendersi tra loro, non per ingannarsi a vicenda”. (Alessandro Manzoni) “Men created language to understand, not to deceive each other”. (Alessandro Manzoni) 4 Copyright © 2010 by the Italian Permanent Mission to the United Nations Editorial, photographs and design by Silvia Cioce, Michael Moore, Angela Carabelli, Riccardo Chioni, and Francesca Lorusso Caputi All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the authors. The only exception is by a reviewer, who may quote short excerpts in a review. The Italian Permanent Mission to the United Nations www.italyun.esteri.it Printed in the United States of America First Printing: December 2010 5 INTRODUCTION Security Council reform; fight against organized crime; peacekeeping and peace-building operations; combating abuse and violence against women and children; UN approval of a universal moratorium on the application of the death penalty; climate change and sustainable development. -

African Union Union Africaine1 União Africana

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE 1 UNIÃO AFRICANA P.O. BOX: 3243, ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA, TEL.:(251-11) 551 38 22 FAX: (251-11) 551 93 21 Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] PEACE AND SECURITY COUNCIL 51 ST MEETING 15 MAY 2006 ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA PSC/MIN/2(LI) Original: English REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON OF THE COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PEACE AND SECURITY COUNCIL DECISION OF 10 MARCH 2006 ON THE SITUATION IN DARFUR AND THE CONCLUSION OF THE ABUJA PEACE TALKS 1 EW/my PSC/MIN/2(LI) Page 1 REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON OF THE COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PEACE AND SECURITY COUNCIL DECISION OF 10 MARCH 2006 ON THE SITUATION IN DARFUR AND ON THE CONCLUSION OF THE ABUJA PEACE TALKS I. INTRODUCTION 1. At its 46 th meeting held on 10 March 2006, Council considered the situation in Darfur. At the end of its deliberations, Council decided to support in principle the transition from the African Union Mission in Sudan (AMIS) to a United Nations (UN) Operation, within the framework of the partnership between the AU and the UN in the promotion of peace, security and stability in Africa, and to extend the mandate of AMIS until 30 September 2006. Council further decided that, during this period, every effort should be made to (a) ensure the early conclusion of a peace agreement, (b) improve the security, humanitarian and human rights situation on the ground, and (c) address the crisis in the relations between Chad and Sudan. -

30 June 2009 Sirte, Libya REPORT of THE

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: 5517 700 Fax: 5517844 Website: www. Africa-union.org EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Fifteenth Ordinary Session 24 - 30 June 2009 Sirte, Libya EX. CL/520 (XV) REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMISSION COVERING THE PERIOD JANUARY TO JUNE 2009 EX. CL/520 (XV) Page i Page FOREWORD I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 8 II. PEACE AND SECURITY III. REGIONAL INTEGRATION, DEVELOPMENT AND COOPERATION 42 III.1 Integration and Human Capital Development 42 1. Education 42 2. Science & Technology 44 3. Information Society 46 4. Health and Sanitation 46 5. Human and Social Welfare 48 6. Children, Youth and Sport 54 III.2 Integration and Development of Interconnectivity 57 1. Transport (roads, railway, air, water) 57 2. Energy (energy crisis); 60 3. Telecommunications, Posts and ICT 64 III.3 Integration and Climate Change and Sustainable Management 66 of Natural Resources 1. Impact of Climate Change and General Issues of Concern (Forest Resources Management, Water Resources 66 Management, Soils Management, Livestock) III.4 Integration and Development of Financial Market and Assets (the Financial Institutions…) 71 III.5 Integration and Development of Production Capacities 77 1. Agriculture (CAADP, Food crisis) 77 2. Industrial and Mining Development 80 EX. CL/520 (XV) Page ii III.6 Integration and Trade Capacity Building 82 1. Market Access Capacity Building 82 2. Multilateral Trade Rules and Negotiations (EPA,WTO) III.8 Partnership and Relations with the World 89 1. On-going Partnerships 89 2. Afro-Arab Cooperation 92 3. Representational Offices 94 4. -

Hon.Rufus Bousquet GA 09.09

United Nations A/64/PV.12 General Assembly Official Records Sixty-fourth session 12th plenary meeting Monday, 28 September 2009, 3 p.m. New York President: Mr. Ali Abdussalam Treki ........................... (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya) The meeting was called to order at 3.10 p.m. consensus reached by the political parties of Mauritania and enshrined in the Dakar Accord. This Agenda item 8 (continued) agreement provided for the elaboration of an electoral agenda supervised by a Government of national unity General debate in which minority parties in Parliament enjoy half of The President (spoke in Arabic): I call on Her the number of seats, including among the sovereign Excellency Ms. Naha Mint Mouknass, Minister for ministries, such as the Ministries of Home Affairs, Foreign Affairs and Cooperation of the Islamic Information, Defence and others. Republic of Mauritania. The normalization of the constitutional process Ms. Mint Mouknass (Mauritania) (spoke in led to the election of Mr. Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz as Arabic): I should like at the outset, on behalf of the President of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania. He Islamic Republic of Mauritania as well as on my own received 53 per cent of the votes during the first round account, to congratulate you, Sir, on your election to of the elections held on 18 July and all national and preside over the General Assembly at its sixty-fourth international observers attested to the transparency and session and to wish you every possible success in your fairness of this election. serious and noble mission. I have a great deal of On behalf of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, confidence that your efforts will bear fruit and enable I convey my special gratitude to the International the Organization to continue to achieve the success Contact Group, and especially to the President of the attained under the presidency of your predecessor, African Union, the Leader Muammar Al-Qadhafi, who Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann. -

Darfur Peace Agreement

DARFUR PEACE AGREEMENT (i) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Abbreviations………………………………………… ii Definitions……………………………………………………………… iv Preamble………………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter 1: Power Sharing ………………………………………… 3 Chapter 2: Wealth Sharing ……………………………………….. 19 Chapter 3: Comprehensive Ceasefire and Final Security Arrangements 41 Chapter 4: Darfur-Darfur Dialogue and Consultation………………………78 Chapter 5: General Provisions……………………………………………… 84 Chapter 6: Implementation Modalities and Timelines…………………….. 85 Annexure 1: Humanitarian Ceasefire Agreement of 08/04/2004, N’djamena, Chad ……………………………………………… 107 Annexure 2: Protocol on the Establishment of Humanitarian Assistance in Darfur of 08/04/2004, N’Djamena……………………………… 113 Annexure 3: Agreement on the Modalities for the Establishment of the Ceasefire Commission (CFC) and the Deployment of Observers of 28/05/2004, Addis-Ababa, Ethiopia…………... 118 Annexure 4: Protocol on The Improvement of the Humanitarian Situation in Darfur of 09/11/2004 Abuja, Nigeria ………………………… 129 Annexure 5: Protocol on the Enhancement of the Security Situation in Darfur of 09/11/2004 Abuja, Nigeria ………………………… 136 Annexure 6: Declaration of Principles for the Resolution of the Sudanese Conflict in Darfur of 05/07/2005, Abuja, Nigeria ………….. 143 www. SudanTribune.com (ii) ABBREVIATIONS ADB - African Development Bank AMIS - African Union Mission in the Sudan AU - African Union CFC - Ceasefire Commission CIVPOL - Civilian Police CMO - Chief Military Observer CPA - The Comprehensive Peace Agreement CPC - CivPol Commissioner CRC -

World Water Day”

HIGH LEVELTHEMATIC DEBATE ON WATER CONCEPT PAPER 22 March, “World Water Day” Water-related issues are at the top of the world’s sustainable development agenda and are relevant to many challenges the global community is facing. This is particularly relevant to the availability and quality of freshwater resources, as well as the issue of access to drinking water and sanitation services. By its resolution 58/217, the General Assembly proclaimed 2005-2015 as the International Decade for Action “Water for Life”, to commence on 22 March 2005, and recalled its resolution 55/196, in which it had proclaimed 2003 as the International Year of Freshwater. Furthermore the General Assembly through the adoption of its resolution 64/198, invited the President of the General Assembly to convene a high- level interactive dialogue (HLID) of the sixty-fourth session of the General Assembly in New York on 22 March 2010, World Water Day, on the implementation of the abovementioned International Decade. The primary goal of the International Decade for Action “Water for Life” is to promote efforts to fulfill international commitments made on water and water-related issues by 2015. The Millennium Declaration commits Governments around the world to a clear agenda for combating poverty, hunger, illiteracy, disease, discrimination against women and environmental degradation. In the area of water resources and sanitation, Heads of State and Government pledged in 2000 to reduce by half the proportion of people who are unable to reach, or to afford, safe drinking water by 2015 and to stop the unsustainable exploitation of water resources. Additional goals adopted at the World Summit on Sustainable Development, held in Johannesburg in 2002, aim at developing integrated water resource management and water efficiency plans by 2005 and at halving the proportion of people who do not have access to basic sanitation by 2015. -

Truth and Justice Can't Wait

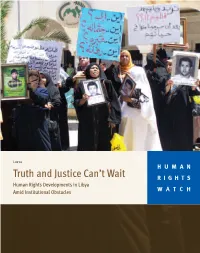

Libya HUMAN Truth and Justice Can’t Wait RIGHTS Human Rights Developments in Libya Amid Institutional Obstacles WATCH Truth and Justice Can’t Wait Human Rights Developments in Libya Amid Institutional Obstacles Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-563-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2009 1-56432-563-6 Truth and Justice Can’t Wait Human Rights Developments in Libya Amid Institutional Obstacles I. Summary ........................................................................................................................................ 1 II. Recommendations ........................................................................................................................